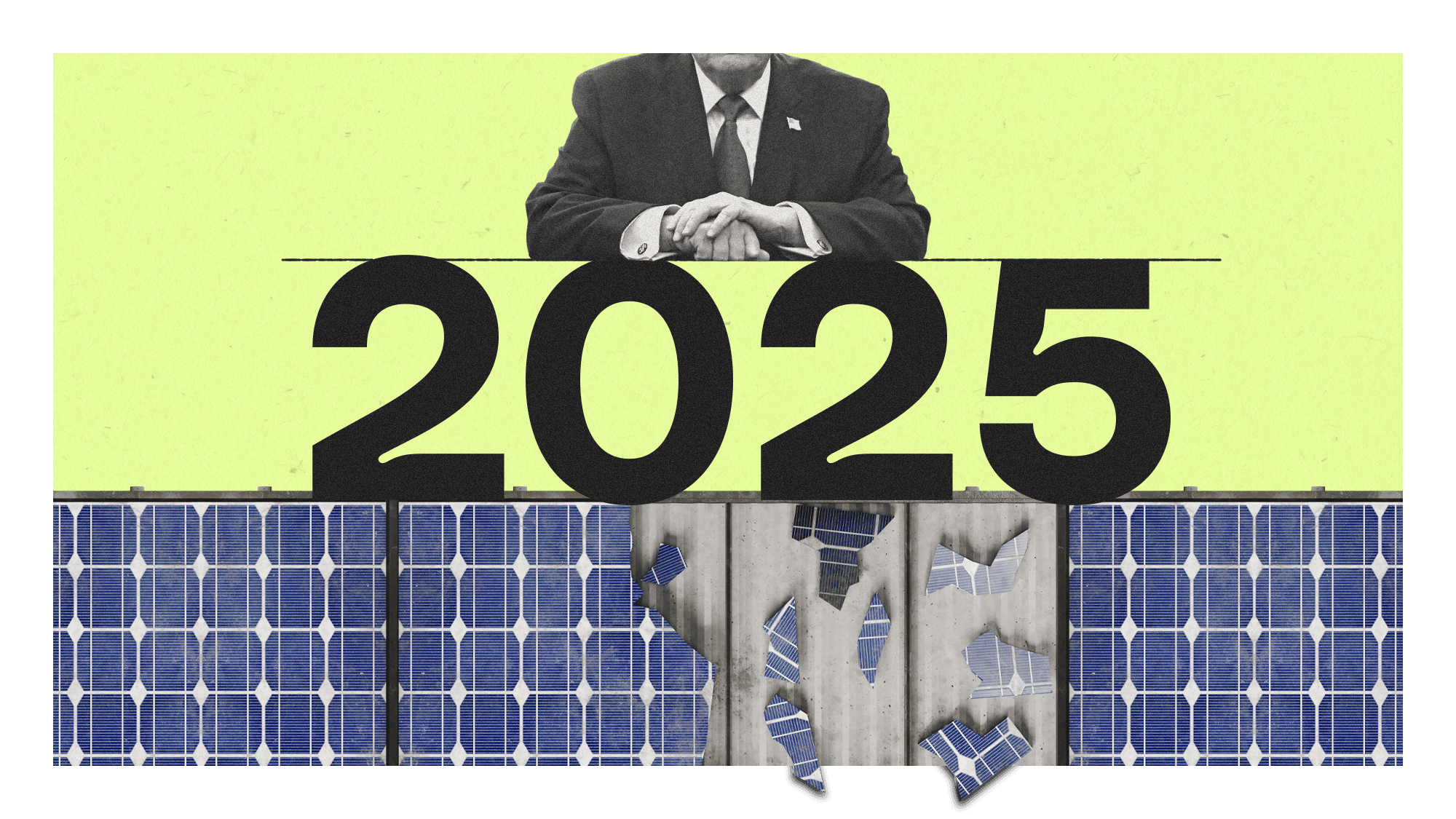

This story is part of a Grist package examining how President Trump’s first 100 days in office have reshaped climate and environmental policy in the U.S.

Jeffrey Willig doesn’t mine coal anymore. For nine years he worked underground, most recently for a company called Blackjewel, which laid off around 1,700 workers in June of 2019 without paying them. Robbed of their final paycheck, Willig and the others set up camp and blocked the company’s last trainload of “black gold” from leaving Harlan County, Kentucky, beginning what would be months of protest. They called on Democrats and Republicans alike for support, and received some, but ultimately were left disillusioned, spending years in court fighting for what they were owed.

Their plight came during a wave of layoffs that has rocked coal country for more than a decade. When Willig heard Democrats discuss mine closures and extoll the growth of clean energy jobs, it frustrated him. “Say they want to do solar panels. That’s great,” Willig said. “But why don’t [they] put those type of jobs in our area? They don’t do that. That’s the problem.”

Democratic party leaders and renewable energy advocates didn’t always seem to understand, he felt, how good a job mining could be. Willig earned $75,000 a year without a college degree, in a county with an annual per capita income not even one-third that. What’s more, it was fulfilling — hard work, and dangerous, but it came with unmatched camaraderie and pride in helping fuel the world. When those jobs were gone, he felt Democrats didn’t provide a clear answer to what would come after.

“They didn’t replace those jobs,” Willig said. “I had guys that I worked with who were good people, and loved their family and everything, and they lost homes.” One friend took his own life, unable to see a way forward to provide for his family.

Harlan County still has many active mines, but, like all of coal country, it has seen layoffs and bankruptcies cut the number of jobs by more than half since 2012. The reasons are complex, but, during his first 100 days in office, President Trump — who has promised to “unleash American energy” and “restore energy dominance” — has reprised a notion he first raised in 2016: Those jobs will come back if environmental and labor regulators simply get out of the way.

Last month, the president appeared with more than two dozen men wearing reflective stripes and hard hats to sign an executive order titled Reinvigorating America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry. “We’re bringing back an industry that was abandoned,” Trump said. “With us today are some of the amazing workers who will benefit from these policies.”

If all of this sounds familiar, it’s because the president’s 2016 run made a star of the Appalachian coalfields. He made regular appearances there, promising to end the “war on coal” by reopening closed plants and reinvigorating the industry. The campaign, which preceded a swirl of national soul-searching that positioned the region, many argued too broadly, as “Trump Country,” featured rallies in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, where the candidate, met by signs declaring “Trump Digs Coal,” donned a hard hat and once pantomimed digging coal.

“You’re real people,” Trump said at one event. “You made this country.”

Andrew Thomas / Middle East Images via AFP / Getty Images

Then, as now, the president was following an example set by politicians before him, said Lou Martin, a labor historian at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Candidates on both sides of the aisle, from FDR and Carter to Nixon and Trump, have dressed the part to campaign in Appalachia, where, despite its dangers, mining coal provided a middle-class living to generations of families.

“The coal miner has always been viewed as the epitome of hard work, a hardworking person who is noble and honest,” Martin said. Appalachia is a popular political backdrop because it is often seen as an epicenter of white rural poverty and “a recognizable world of suffering” for some voters. “Appalachia is seen as white in the national imagination,” he said, despite being home to a people from a diverse set of backgrounds for hundreds of years.

At the same time, Martin said, the Eastern coalfields have often been stereotyped as both out of step with modernity and left behind by progress. “When somebody pays homage to coal miners it’s like saying, ‘I see you and I care about you.’”

The order Trump signed on April 8 declares coal a “critical mineral,” a designation that requires a host of federal agencies, including the energy, treasury, and interior departments, to take steps to support the industry and eliminate regulations that hinder domestic production. Many of those gathered around Trump applauded the move, which comes even as the administration has taken steps to undermine mine safety and protection from black lung disease.

But little about the ceremony was representative of the working-class miners Trump’s campaigns have venerated, said Erin Bates, communications officer for the United Mine Workers of America. “Not a single one of those were union miners and most of them were management,” she said, men more likely wear sharp button-downs than hard hats and go to bed without having to shower first.

Bates wants to see mines remain open and miners remain at work, but she doubts the Trump administration can overcome the trends driving the sector’s downfall. Industry experts predicted in 2017 that the market forces sidelining coal were too strong and the its resurgence is unlikely, and so far they’ve been correct. The number of people working the nation’s coal mines has steadily declined from 89,000 or so in 2012 to about 41,300 today. Production fell 31 percent during Trump’s first term, and has continued that slide.

“He hasn’t spoken about coal miners quite as much as he did in 2016,” Bates said of the president. “And I think that’s because he wasn’t able to follow through on a lot of things.”

The reason for that is simple: Demand has slowed as renewable energy and, to a larger extent, natural gas have grown cheaper, making coal an increasingly expensive proposition — even as the cost of maintaining the power plants that use has climbed. Such facilities provide 88 percent of the electricity in West Virginia, and the longer they run, the more residents will pay for energy, West Virginia Public Broadcasting reported. That’s got some ratepayers turning against the fossil fuel.

Utilities like Appalachian Power have continued to raise rates to keep up with repair costs. Others, like the Tennessee Valley Authority, are decommissioning aging and expensive coal-fired plants and turning to natural gas. Coal-powered electricity generation steadily declined during the first Trump administration, and continues apace. A recent report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis argued very few idled coal plants could be cheaply re-started, given high maintenance costs and the decreasing viability of coal power.

Given the domestic decline in consumption, many U.S. producers rely upon exports to countries like China — 14 percent of the nation’s coal went abroad in 2022 — but the trade war stemming from Trump’s tariffs threatens that lifeline.

Scott Olson / Getty Images

Trump still enjoys broad support throughout eastern coalfields. “I think that he meant every word, he wanted to make the country more energy efficient. The guys that I worked with had high hopes,” Willig said, adding that he felt four years wasn’t enough time to enact real change.

Cathy Davis Estep, a retired teacher and the daughter of a coal miner who lives in Harlan County, remains hopeful that Trump will revitalize the industry. She takes note, however, that the administration has targeted at least 33 Mine Safety and Health Administration offices, including the Harlan County location, for closure. This comes after years of staff reductions and budget cuts to the agency had already wrung it of much of its power. Miners and their advocates fear the closures will diminish an agency that’s improved safety over the past 50 years or so despite its shortcomings and could play a vital role protecting them as the Trump administration promotes coal and the nation scrambles to produce lithium and other metals.

Vonda Robinson is vice president of the Black Lung Association and feels she has a handle on what miners need. Her husband dug coal until he contracted the disease, which is caused by chronic exposure to silica dust, in his 40s. Now 58, he is awaiting a double lung transplant. Many others are awaiting diagnosis and treatment, but Trump administration policies have stymied them. “We’re gonna have coal, we’re gonna dig baby dig, but what upsets me is there’s not one thing about safety,” she said. “If we do not take care of our coal miners, we’re not gonna have a coal industry.”

Miners’ health programs are shuttering, with immediate impacts, said Scott Laney, a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or NiOSH, epidemiologist. His staff was put on leave last month and expects to be fired in June. His research laid the groundwork for the federal silica rule, which limits exposure to the toxic dust. The rule was adopted last year, but has been placed on hold pending a legal challenge by the National Sand, Gravel, and Stone Association, and NiOSH cuts have held up enforcement regardless.

Laney’s research also supported the Coal Workers Health Surveillance Program, which provided free black lung screenings throughout Appalachia. “We currently are unable to accept X-rays from clinics for these miners, we’re unable to go out in the field,” he said. Nor can the program provide the documentation essential to allowing workers diagnosed with the disease to transfer to roles with less exposure to silica, as required by law.

“As we potentially increase coal production in the United States, we’re in the midst of the worst outbreak of black lung that we’ve seen in the last 50 years and we’re shutting down the health and safety programs to protect these miners who may be entering the industry for for the first time,” Laney said. “The protections that were granted to their fathers and their fathers’ fathers will not be afforded to them.”

Even as Trump promises to revitalize an industry facing inevitable decline, its future remains uncertain. But Willig won’t be a part of it. He’s long since left the coalfields for a manufacturing job in Louisville, Kentucky. But he watches with a combination of frustration and hope as Democrats and Republicans alike promise to restore the fortunes of those who, like him, once enjoyed the middle class life that working underground once provided.

Source link

Katie Myers grist.org