1. Introduction

Currently, anthropogenic climate change, exacerbated by the use of greenhouse gas (GHG)-dependent energy sources, is one of society’s most pressing issues; subsequently, a majority of national and international governmental policy attempts to address these issues via mitigation and adaption strategies [

1,

2,

3]. Many sectors of the built environment have contributed directly and indirectly to the accumulation of GHG in our atmosphere, such as electricity production, heat production, transport, and equipment [

4]. These sectors underpin our modern global economy, which is vital to the continued growth and modernization of societies around the globe. Moreover, these sectors are often dependent on electricity production and distribution from the grid to meet their current electrical needs, with a majority of this energy being consumed by equipment and lighting. Considering that if sustained healthy economic growth is to continue, current systems will need to be adapted with alternative sustainable solutions to mitigate the use of fossil fuel energy systems such as RES; however, this transition requires thermal and transport energy to transition from fossil fuel-based systems (i.e., combustion engine, domestic and commercial boilers) to electrical systems, which increases demand on the electrical grid. With the growing RES and electric-powered systems, the current grid is not equipped to handle the complex bi-direction loads from RES and excess energy loads from the electrification of the built environment and will thus need to adapt [

5,

6]. As a result, there is a growing paradigm shift in the distribution of electrical energy from centralized to de-centralized, where energy is beginning to be managed closer to the demand side rather than the source. New methodologies for optimizing demand side management (DSM) have recently begun to trend, such as peer-to-peer energy (P2P) energy trading, which will be explored in greater detail in the following sections of this paper.

The electrical grid has evolved to cater to new demands in the past for both residential and non-residential energy consumption; however, with ambitious new climate policy and evolving aforementioned paradigm shifts in energy generation and distribution, new challenges have arisen that require novel approaches to achieving climate objectives [

2,

7]. With the advancement of electrical-dependent technologies such as electric vehicles (EV), heating systems, and smart appliances, among a plethora of other devices in use today, coupled with the proliferation of distributed energy resources (DERs), such as photovoltaic (PV) and storage technologies, the grid must cope with larger demands and disturbances as well as bidirectional energy flows for which it was not originally designed [

7,

8]. Consequently, new DERs on the grid reduce the dependency on centralized generators such as gas, nuclear, and hydro turbine generation, which reduces the amount of available inertia that supports grid stability during disruption; however, counterpoise to loss of inertia, DER can also provide stability by leveraging storage technologies such as batteries to maintain grid stability. Given these factors, distribution system operators (DSOs) and transmission system operators (TSOs) now need to adapt and leverage these technologies towards stable grid operations and constant and reliable energy for end-users practically during natural and anthropogenic disruptive events (storms, earthquakes, or malicious attacks) and demand side generation (wind and PV curtailment, heat waves, local/national events) [

7,

8,

9,

10]. To this end, the propagation of information communication technology (ICT), Internet of Things (IoT) hardware/software technologies, and 5G communication has enabled sophisticated solutions to address the above issues with the grid, allowing stakeholders to better manage complex grid loads and disruptions [

11,

12,

13].

Grid management has evolved not only to cope with an expanding grid but to better manage and optimize resources related to the grid, often leveraging IoT technologies. For example, dynamic line rating (DLR) leverages thermal sensors distributed across the grid to allow for dynamic rating of the line’s capacity to handle loads. Historically, line ratings were static to ensure the operators did not exceed the load, potentially causing voltage surge damage to the asset; however, these ratings are often conservatively low to better protect the asset. With DLR, operators can exceed the power lines’ static rating to cope with excess loads based on the local temperature, as temperature impacts the capacity of lines to cope with energy loads. Demand response (DR) is another feature that has been improved by IoT technologies. Smart-enabled equipment in buildings can now receive signals from grid operators towards load shifting and renewable curtailment to better manage the grid and reduce energy losses [

5,

13]. IoT has enabled two-way communication between operators and users, which has brought on the inception of the smart grid (SG). Not only can SG optimize energy use on the grid, but, as mentioned previously, it improves grid resilience during disruptive events by utilizing features such as self-healing grids or backup RES and storage systems [

14,

15]. Moreover, the potential for smart microgrids that are isolated from the national grid could benefit greatly from the aforementioned technologies by enabling seamless local bidirectional flow, optimization of local renewable assets, and optimal cost benefit for tariffs for local consumers by utilizing P2P trading technology [

16,

17].

Recently, P2P grid concepts have grown in popularity due to their potential to optimize DER assets towards better financial outcomes for consumers and improved DR for operators in line with the current paradigm shift towards decentralization of national grids, which in turn creates a more resilient and reliable grid infrastructure. In P2P systems, the network comprises of users who are both producing and consuming energy; these producing consumers are known as prosumers [

8,

17]. These prosumers trade surplus energy with buildings on their local grid network, which is incentivized via financial benefits such as feed-in tariffs that are worth more than the current prices for trading with the network provider and less than the current tariff that standard consumers would pay at the time the surplus energy is available. P2P operations have been largely limited to theoretical desktop and small-scale pilot studies [

17,

18,

19]. From the literature, at least four cornerstone technologies are key to the large-scale adaptation of P2P, namely (i) smart metering devices, (ii) a software platform underpinned by blockchain supported with load management algorithms, (iii) a strong communication network for low latency communication (5G), and (iv) DERs distributed across the grid. However, many of these technologies are still in their infancy and need some maturity to ensure security from data breaches and cyber threats, as well as improved 5G coverage towards optimal responsiveness from critical IoT devices. Moreover, in most P2P use cases, current regularity frameworks are prohibitive towards fully operational P2P networks as, much like the grid itself, they have been drafted to cater to top-down grid architecture, which lacks the versatility to cater to bidirectional flows across multiple actors [

20,

21].

Despite the current challenges of P2P, new advancements in communication, transport, building energy, and renewable energy technologies culminate in opportunistic solutions to reduce the costs of grid reinforcement by optimizing current and future DER on the grid via P2P implementation. Current literature on testing P2P, either in real-world conditions, mathematical simulations, or a combination of both, and sometimes coupled with gaming theory, often demonstrates positive results in their applications by increasing local consumption of RES, reducing energy transmission loss, and increasing financial benefits for prosumers [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Furthermore, advancements in technology, such as AI, can improve the performance and security of these P2P networks, supporting their proliferation into the future [

26]. Often, these studies use digital twins (DT) to virtually represent network actors, assets, and local environments to predict P2P performance towards real-time management, cost–benefit analysis, and supporting policies and regulations relating to the grid [

22,

27].

Naturally, most of this multidisciplinary research discussed so far is conducted within the realms of electrical engineering, particularly in fields concerning grid networks, RES, and DER; however, as the power grid plays a key role in decarbonization policy for achieving ambitious climate change objectives, it is imperative that fields relating to climate change and the grid reflect these changes too. In building energy, research on the decarbonization of buildings involves applying novel, efficient electrical technologies that are dependent on the continued decarbonization of the grid [

28,

29,

30]. Building energy models (BEM) and urban BEM (UBEM) use predictive physics-based DT to predict buildings’ energy performance over a calendar year towards optimizing energy consumption at the building and city scale, respectively. These models estimate equipment, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), lighting, and domestic hot water (DHW) loads to determine how energy-efficient buildings are. In retrofitting scenarios, these system properties are often replaced in favor of more energy-efficient, electricity-dependent systems. These models often underpin building regulation policy and support the decarbonization roadmaps for local and national governments [

28,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

BEMs are often used for building compliance in the design stage, generating energy performance results, and testing retrofit strategies for decarbonization and energy optimization. UBEMs offer the same capabilities with rapid results at a large scale; however, rapid results at scale come at the cost of reduced accuracy due to computational limitations. Despite the reduced accuracy, UBEMs can still test PV, storage, and district heating/cooling strategists with reasonable accuracy, which is suitable for predictive models at district and city scales [

35,

36,

37]. Currently, physics-based UBEMs have grown in popularity in addressing large-scale energy master planning strategies for both existing and future building stock towards decarbonization of building stock, improved performance of district cooling/heating systems, and grid development strategies [

31,

33,

37,

38].

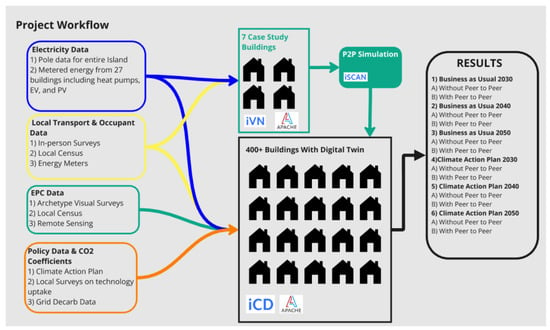

In this paper, IoT energy metering sensors coupled with detailed building, network, and socioeconomic data from onsite surveys, local and national databases, and remote sensing data are used to develop a physics-based UBEM model (intelligent community lifecycle, ICL) DT (

https://www.iesve.com/digital-twins https://www.iesve.com/discoveries/view/3828/introducing-icl-film accessed on 1 September 2024) of a small island community off the west coast of Ireland, Inishmore. This research uses the DT to assess the potential contribution that P2P energy trading can make in supporting decarbonization roadmaps. This work aims to leverage existing state-of-the-art technologies to support local and national policy and decarbonization roadmaps by incorporating the current paradigm shift in the national grid with building decarbonization roadmaps to leverage their geographical and user profile juxtaposition towards optimal energy use of existing and future DER implementation on this remote island. The following sections describe the structure of the research, with

Section 2 demonstrating the methodology, data, and technology used in developing this DT;

Section 3 describes the results;

Section 4 discusses the findings; and

Section 5 concludes the key findings from this paper.

4. Discussion

The IDT produced sub-hourly data on the island’s energy loads, which enabled a dynamic assessment of energy consumption and production for various potential future scenarios for Inishmore. The impacts of P2P on local RES consumption have notable benefits and demonstrate the potential use of onsite surplus energy, although, in PV-saturated markets, these benefits are modest. Although the methodology does not capture the technical and behavioral influences associated with sophisticated P2P energy trading, such as blockchain or smart contracts, it does highlight the potential savings and limitations in implementing P2P. On average, each scenario for P2P demonstrated savings between 2–54% of onsite consumption of renewables, which would have otherwise been sold back to the grid or curtailed, resulting in losses. However, the methodology’s limitation is its inability to account for how surplus energy may have been consumed and the potential positive impacts that may have had, which other methods such as gaming theory, economic models, and blockchain simulations could have potentially captured. Nevertheless, for the scale of its application, the authors believe that this is a reasonable assessment of potential P2P simulation at a neighborhood scale.

Technical obstacles in implementing real-world P2P have been identified during the implementation of the methodology for this paper. Moreover, sociotechnical obstacles have been identified, but the scope of this paper was limited in addressing obstacles of this nature. Given the remote nature of the pilot site, common data that are generally available nationally were limited, such as real-world EPC and remote sensing data, which were symptomatic of wider coverage and connectivity problems across this remote part of the grid. In terms of connectivity, three of the original ten use case buildings were omitted due to poor 4G signal, which resulted in data gaps, rendering them ineligible for inclusion in the study. Moreover, data latency is another factor in energy trades, as most trades are optimally executed, as dependable connectivity is a vital component in any P2P network, as energy trades happen in real time, and any latency or data gaps reduce or prevent the ability of the network to trade. In Ireland, over 90% of properties have some sort of internet connection; however, internet speed varies widely depending on geography, which is often slowest in rural areas due to the slow proliferation of novel technologies due to dispersed populations, such as fiber optic broadband rollout (

https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-isshict/internetcoverageandusageinireland2022/householdinternetconnectivity/ accessed on 10 September 2024). Ultimately, poor signal and internet speeds impact the ability of P2P networks to trade optimally. Moving forward, increased rollout of 5G coverage, coupled with strategic placement of IoT equipment, should mitigate the impacts of slow or lost signals.

Sociotechnical issues relating to current policy regarding smart energy communities on the grid will need to involve more stakeholders related to the grid infrastructure and communities. Currently, only registered energy aggregators are able to operate energy-sharing schemes on a large scale on the Irish grid. The DSO has attempted to trial the P2P project in Ireland but took a top-down approach focusing on local suppliers and their ability to enable P2P; however, this attempt was unsuccessful due to poor stakeholder commitment due to differing views on the rollout of P2P and what the market place would look like, as well as uncertainty around the introduction of a clean energy policy, which derailed the project [

42]. Furthermore, in Ireland, neither the Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU) nor the Irish government has developed meaningful policy that supports P2P with regard to energy communities; moreover, to the best of the author’s knowledge, no substantial policy or projects have been fully realized in Ireland yet [

42,

43]. Based on the success of onsite surveys during the application of the methodology of this paper, the authors suggest a bottom-up approach to stakeholder engagement could be more effective if both technical limitations, such as the aforementioned data and connectivity gaps, as well as sociotechnical, with the DSO engaging with end-users and suppliers to identify opportunities and how to facilitate the development of the grid towards more secure energy trading infrastructure, which could enable a path forward for P2P proliferation.

Scenarios two, three, five, and six demonstrated modest gains after P2P applications. These scenarios captured a marketplace that was saturated with up to 80% of buildings that were installing PV on their roof space without storage. These scenarios demonstrate the importance of DSM, which can be better facilitated via storage assets such as batteries, vehicle-to-grid EVs, or even smart DHW tanks or behavioral change towards using equipment at off-peak times. This would increase the potential for onsite consumption at appropriate times and enable more sophisticated local P2P trades as users could tailor better-preferred trades to cater to their energy needs.

Finally, the IDT has the potential to support complex decision-making for intricate systems such as national grids. With a myriad of new technologies interacting at the regional scale, it is difficult to curate policy that leverages all novel technologies towards larger goals such as decarbonization strategies. The IDT in this project was capable of making predictions on peak energy loads that could potentially overload the current infrastructure, which demonstrated that CAP2050 peak loads have the potential of overwhelming 1.5 MW, assuming that this is the current capacity of the line. Moreover, if the IDT had more accurate information on the current state of the grid as well as specific infrastructural specs, P2P loads could have been tested to see if they could mitigate grid reinforcement. Future scenarios and tests could be investigated in future research, such as the cost–benefit of P2P and local energy storage.