1. Introduction

The global mortality rate among children under five years of age declined by 59%, from 93 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 37 deaths per 1000 live births in 2022 [

1]. This significant reduction has been primarily attributed to the provision of childhood vaccinations, contributing to achieving the fourth United Nations Millennium Development Goal, which aimed to promote healthy lives for children and eliminate preventable deaths among newborns and young children [

2]. Although substantial progress has been made in improving child survival, the magnitude of under-five mortality remains a significant burden in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [

1,

3]. Hence, continued efforts to reduce child mortality further are imperative.

In addition to the apparent health benefits, vaccination of under-five children is highly considered the most cost-effective, reliable, and robust public health intervention for curbing morbidity and mortality associated with preventable diseases [

2,

4]. Globally, immunization coverage has vastly expanded to cover all countries with the services available and accessible to rural and urban citizens of every nation [

5]. In recent years, more efforts have been directed toward strict adherence to the vaccination schedule to immunize the under-five with vaccines such as Diphtheria–Tetanus, Measles–Rubella, and Polio [

6]. The World Health Organization, in collaboration with governments of other countries, has implemented different strategies to upscale vaccine uptake among children [

2]. As a result, these strategies increased the delivery of vaccination services and raised citizens’ awareness of the vaccination benefits to under-fives. Yet, millions of children in Africa are still deprived of life-saving vaccinations, accounting for nearly half of the world’s unvaccinated and under-vaccinated children [

7].

Sub-Saharan African countries, particularly Tanzania, have recorded remarkable successes in nationwide child immunization coverage, attributed to vaccine availability, effective vaccine delivery mechanisms, and community sensitization and vaccination promotions [

8]. Despite these accomplishments, significant challenges remain, including high rates of under-five mortality [

9] and a considerable number of zero-dose and under-vaccinated children due to vaccine hesitancy [

10]. In Tanzania, one in four children are not fully vaccinated. Many regions fail to meet the 90% coverage target set by the Reaching Every District (RED) strategy [

10], and according to the WHO (2023), Tanzania, Angola, and Cameroon ranked among the top ten African countries with the highest numbers of zero-dose children in 2022 [

11].

Various factors contribute to vaccine hesitancy, including trust, occupational status, education, marital status, wealth, place of residence, media exposure, and access to antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC) [

12,

13,

14]. These factors are shaped by social, economic, and cultural dynamics influencing parental vaccine awareness. For instance, the lack of trust in vaccines and healthcare practitioners is often fueled by misinformation, cultural beliefs, and past negative experiences with vaccination [

13,

15]. This distrust is a key factor contributing to the lack of confidence in the efficacy and safety of vaccines. Both occupations and education influence the extent to which an individual is exposed to vaccine-related information. For example, healthcare workers are exposed to detailed vaccine information, which can lead to either high acceptance or hesitancy [

12,

14]. Parental marital status can also influence vaccination hesitancy, as making a decision about whether to vaccinate a child often requires agreement between both parents [

12,

16]. Individuals with stable and higher financial resources generally have better access to healthcare services and vaccine-related information, making them more likely to accept vaccines compared to those with limited financial resources and influenced by other beliefs [

14,

17]. There is a critical need for effective interventions to overcome these barriers and ensure that children from hesitant families receive vaccinations. According to the WHO, interventions targeting vaccine hesitancy should be specifically tailored to the concerns of the respective target population to maximize their effectiveness [

18].

Human-centered design (HCD) is a more ethical and practical approach to addressing public health challenges in complex sociocultural settings [

19]. As conceptualized by the IDEO (2015), HCD emphasizes creating interventions tailored to the target population’s needs, preferences, and experiences [

20]. This approach prioritizes collaboration with end-user communities, engaging deeply with the impacted individuals and groups. By fostering this co-creation process, HCD ensures that solutions are effective, culturally, and contextually relevant, making them more sustainable and likely to succeed [

21]. Despite the substantial contributions of HCD in addressing complex problems in public health, there is a lack of empirical evidence describing the implementation of an entire HCD project [

19]. Most studies are centered on one or two aspects of HCD, i.e., stakeholder engagement [

22], ideation [

23], or prototyping [

24]. To address this gap, this study described the use of the HCD approach in identifying, prioritizing, and implementing community-centered interventions to increase vaccine demand and close the zero-dose gap in Tanzania, focusing on the Ilala District in Dar es Salaam. Ilala is the leading district in Dar es Salaam, with a high number of zero-dose and under-vaccinated children [

25]. The intention was to reduce the number of children with zero doses of Diphtheria–Tetanus–Pertussis (DTP) and Measles–Rubella (MR) vaccines by at least 50%. Key stakeholders, mainly caregivers, community health workers, healthcare providers, parents, and religious and community leaders, were actively engaged throughout the HCD process, ensuring that solutions were developed collaboratively with the direct beneficiaries.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: the materials and methods section outline the research design, including co-creation workshops, data collection, analysis, challenge definition, solution design, and implementation methods. The results section presents findings on barriers to routine immunization, key opportunities for generating innovative solutions to reduce the zero-dose gap in Ilala, interventions, prototyped solutions, and their implementation. The discussion interprets these findings about the research objectives and relevant literature. Finally, the conclusion summarizes key insights, offers suggestions for improving digital systems, and highlights directions for future research.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information

As shown in

Table 1, the research involved a diverse group of 483 participants, with 24 consistently engaged throughout all phases of the human-centered design (HCD) process.

Table 2 presents a list of participants involved in testing ideas and prototypes. Such stakeholders were categorized into various groups: researchers from higher learning institutions (HLIs); national government officials, mainly from the Ministry of Health (MoH); regional and district government leaders such as the Regional Medical Officer (RMO), District Executive Director (DED), District Commissioner (DC), mayor, and the Council Health Management Team (CHMT); local government leaders such as ward executive officers (WEOs), Mtaa executive officers (MEOs), Mtaa chairpersons, environmental health officers, and members of local government councils; civil society organizations such as the Shivyawata–Tanzania Federation of Disabled People’s Organizations, the TADIO network of community radio stations in Tanzania, the Chavita (association of people with hearing impairment), and BBC Media Action; community health workers (CHWs) and caregivers; and international organizations such as UNICEF, WHO, JHPIEGO, and AMREF.

3.2. Identified Barriers and Key Opportunities

Based on a rapid inquiry and observation, multiple barriers to routine immunization, as depicted in

Table 3, were identified from various perspectives, including those of fathers, female caregivers, community health workers (CHWs), religious leaders, healthcare workers (HCWs), community leaders, and grandmothers. Each group faces unique challenges that impact the delivery and uptake of vaccinations.

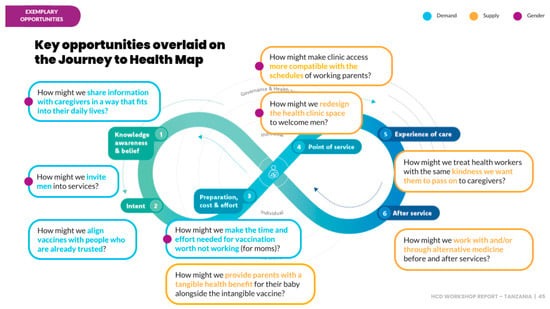

From these identified barriers, nine key opportunities emerged, as shown in

Figure 1, that were leveraged to generate innovative solutions to reduce the zero-dose gap in Ilala. These opportunities provided a foundation for targeted interventions to address each stakeholder group’s specific needs and concerns, ultimately increasing immunization coverage in the region.

3.3. Identified Interventions

From five opportunities, 309 ideas were generated through a collaborative brainstorming process involving diverse stakeholders, as summarized in

Table 4.

3.4. Prioritized Interventions

Of 309 ideas generated, 49 were prioritized after thorough discussion and broad thinking. The criteria used for prioritization were desirability, viability, and feasibility. These 49 ideas were then ranked through a participatory approach, with each idea being reviewed and discussed in detail. From this ranking process, the top six ideas listed in

Table 5 were selected for further exploration.

During the discussions, participants highlighted key issues and questions, pointing out barriers and opportunities that could be explored further. One notable opportunity is the government’s directive for health facilities to allocate resources through Health System Financing to enhance the capacity of CHWs. This initiative presents a valuable opportunity to strengthen CHW support. However, challenges remain, such as traditional healers’ reluctance to partner with healthcare providers, suggesting that their views and needs should be incorporated into the design process. Additionally, there were concerns about the effectiveness of initiatives to invite fathers and make clinics more male-friendly, with participants questioning the value of such efforts if the vaccination environment remains unwelcoming. Finally, the current guidelines prioritize men who bring their children for vaccination, highlighting a potential area for further development and reinforcement.

3.5. Prototypes

Prototypes of the top six ideas were created in different forms, not limited to sketches or storyboards on rough papers or even role play scenarios. These prototyped ideas were iteratively tested (three iterations). Feedback from the community was collected after each iteration, allowing the ideas to be refined and improved. As a result, three (3) of the most desirable and impactful ideas emerged, shaped by the inputs and suggestions from the community. The three ideas that emerged are summarized in

Table 6. It was also observed that community members preferred and emphasized the involvement of CHWs in all the ideas. Therefore, the idea of the capacitation of CHWs was merged into the three selected ideas, and new versions for each idea were created. Three rounds of iterative testing were conducted on the refined versions of the three chosen ideas, with feedback from each round used to further enhance the prototypes up to version 3.

3.6. Prototype Implementation

The selected idea for implementation was advocacy through community leaders and community health workers (CHWs). Preparations for this implementation included creating a human-centered advocacy implementation plan involving collaboration with various stakeholders. The advocacy prototype was refined during this process based on feedback from the planning phase.

The refined prototype, as shown in

Figure 2, underwent several modifications. Firstly, it broadened stakeholder inclusion by integrating previously omitted council leaders, such as the District Commissioner (DC), the Mayor, and the District Administrative Secretary (DAS). Secondly, the prototype streamlined the advocacy process by condensing the original four stages into two while still ensuring the participation of all relevant advocacy groups. The focus of the original prototype involved the DC advocating to ward-level leaders and Mtaa leaders (local/street leaders), who subsequently advocated to CHWs. However, since it was discovered during design research that CHWs maintain a closer relationship with the community, a more impactful approach would be for the DC to directly advocate for CHWs alongside ward leaders and Mtaa leaders (local/street leaders). Therefore, the advocacy flow was revised: the DC was now to advocate directly to council and community leaders. Community-level advocacy was restructured to incorporate the involvement of community health workers (CHWs), ward-level leaders, and street-level leaders.

During council-level and community-level advocacy, the DC championed vaccination to 430 participants, including government officials, regional leaders, district leaders, heads of departments, CHMTs, community leaders, CHWs, HCWs, media officers, and journalists.

House-to-house mobilization and sensitization commenced immediately after the advocacy meetings in 26 wards in the Ukonga and Segerea Constituencies. Depending on the established criteria, the house-to-house mobilization process spanned five or ten days per ward. Each of the 189 CHWs paired with an HCW was assigned a daily house-to-house target of 40 households, assuming an average of 4 families per household and 160 families per day. Ward Health Officers supervised house-to-house mobilization exercises, verified daily vaccination data, and confirmed visits with photos of house numbers or postcodes. Special tools were created to gather and organize vaccination data at community, ward, and council levels. The tool was designed to record the number of families reached, zero-dose cases addressed, defaulter cases resolved, and the total count of children in each family and household. As a control measure, the Mtaa chairperson verified and stamped the daily data report for each CHW. CHWs were to document visited families.

The data collection tool used during the house-to-house vaccine mobilization exercise also included fields to capture challenges, achievements, and views from CHWs, HCWs, community leaders, and community members. The data collected were analyzed, and it was observed that the challenges, successes, and opinions were related to the following thematic areas: RCH Card, Infrastructure, Tools, Community Participation, Resources, Availability of Children, and Vaccine Education.

Table 7 summarizes the key challenges frequently highlighted by the participants. Most of the feedback from community leaders and families was positive, highlighting that most families were cooperative and loved empowering CHWs to mobilize families alongside HCWs. A notable recommendation was that prior notifications should be provided through PAs, radios, and TV.

In the planning phase, it was initially estimated that, on average, four families resided in each house within the Ilala area. However, subsequent observations revealed a variance in the ratio of families to houses across different divisions. Specifically, in Ukonga, the ratio was two families per house, whereas in Segerea, the ratio was three families per house. Outliers may have influenced the estimated ratio of families per house, as some houses in Ilala were found to accommodate huge families, with numbers reaching up to 16 families per house. During the exercise, 67,145 houses were visited (104% of the goal) as summarized in

Table 8 and shown in

Figure 3. Within these visited houses, 156,995 families were recorded, of which 131,088 (83%) were offered vaccination services.

Table 2 shows the number of zero doses and 1753 defaulters. However, as depicted in

Figure 3, fewer zero doses (387) were identified during the vaccination exercise, while a significantly higher number of defaulters (9899) were identified. While the results may be alarming, they align with the HCD problem diagnosis and research findings. These findings revealed that Ilala, the central urban hub in Dar es Salaam, attracts frequent family movements. Documenting children as defaulters may not accurately reflect their vaccination status, as there is a high likelihood that they moved and received vaccination services in HFs other than the ones they were born in. The frequent movements within and outside of Ilala highlight a pressing challenge: the need for a mechanism to track the vaccination process and synchronize vaccination records within Ilala.

3.7. Identified Theory of Change

The theory of change aims to map out the system of people and activities that are assumed to collectively bring about the desired change. It provides a framework for collaboratively monitoring progress over time, ensuring that each step taken contributes to long-term goals. By tracking intermediate outcomes along the way, the approach ensures that all stakeholders are aligned and working towards common objectives.

Table 9 depicts the theory of change for each persona built from identified barriers and co-created ideas. For instance, to have increased vaccine coverage in Ilala by 50%, CHWs need to be empowered to take on responsibilities such as administering vaccines, keeping records, and weighing babies. As a result, the workload for HCWs is significantly reduced. This leads to improved work–life balance for HCWs, resulting in a more positive clinic environment and the potential to extend clinic hours. As a result, families are more likely to attend and support regular healthcare services, leading to increased trust and accessibility.

4. Discussion

The use of HCD as a framework of this study helped involve and engage local community leaders, health workers, community health workers, and local communities of the study area to identify community-specific impediments to vaccination of under-fives and determine the possible solutions to address the issue. This design emphasizes the need for vaccination interventions to involve the target population in the ideation, prototyping, and implementation stages. The study established the root causes of under-fives defaulting and the zero-dose gap. Among the challenges identified were the inadequate support from local community leaders in sensitizing and monitoring under-five vaccinations, poor infrastructure (especially roads) to newly settled areas during the rainy season, parental hesitancy and unwillingness, limited involvement of male spouses, the absence of house numbers, and the lack of an effective surveillance and notification system. These challenges align with findings from Vasudevan et al. [

10], Shearer et al. [

26], Hogan and Gupta [

33] and Reñosa et al. [

34].

Efforts to bridge the zero-dose gap among under-fives in Tanzania and the rest of the Sub-Saharan countries of Africa highly depend on the availability and proper record-keeping of vaccination data [

25]. As evidenced by this study’s findings, there needed to be more official data on unvaccinated children held by official designated authorities and those gathered in the study area. For example, the existing official vaccination data of the Ilala district showed that zero-dose vaccination is the most persistent vaccination challenge among the under-fives in the district, but this study found the opposite. As summarized in

Figure 3, the study results suggest that vaccine defaulting among under-fives is the prevailing problem. According to the results, the district had a higher number of vaccine defaulters compared to the number of unvaccinated children. Consequently, the prevailing data discrepancies may lead to duplication of efforts and wrong demand-creation interventions.

The mismatch between existing official vaccination data and the field data collected in this study can be attributed to several factors. One major issue is the lack of an effective tracking and notification system for identifying vaccine defaulters, recording routine vaccination data, and sending reminders to parents and guardians. The current system relies on printed cards where healthcare workers manually record vaccination details, which are then kept by parents or guardians. This system poses challenges: cards can be lost, and parents may forget to check or remember vaccination dates. Additionally, some healthcare workers fail to record subsequent vaccination dates accurately. Consequently, this results in vaccine defaulting among under-fives. These findings align with existing research, which links parents’ forgetfulness and inadequate knowledge of vaccination schedules to incomplete vaccinations [

35,

36,

37]. Similarly, the lack of vaccination cards has been linked to non-adherence to immunization schedules [

38].

Moreover, families migrating into the Ilala district and seeking better maternity services have led to incomplete vaccination records when they return to their regions of origin after the initial doses of vaccines such as DTP1 and BCG. This migration has contributed to a rise in vaccination rates for some vaccines, like DTP and BCG, while rates for others, such as MR2, have declined. Additionally, the rapid expansion of new settlements in the district, characterized by high population density, fertility rates, and limited access to health services, exacerbates vaccine defaulting. Due to transport challenges, mobile vaccination services, such as Huduma Mkoba, are infrequent in these areas.

The rapid urbanization and expansion of new settlements contribute to persistent vaccine defaulting and zero-dose cases among under-fives. These findings are consistent with Sambayuka et al. [

25], who identified rapid urbanization in Dar es Salaam, particularly in the Ilala district, as a factor in persistent zero-dose and under-vaccination issues. The study also highlighted that the under-capacitation of healthcare workers impacts the delivery of vaccination counselling and contributes to vaccine hesitancy and defaulting.

Notably, the achievement of targets, as shown in

Figure 3, confirms that face-to-face interpersonal communication through house-to-house vaccination advocacy effectively addresses the zero-dose gap and reaches vaccine defaulters. This approach facilitates the accurate capture of vaccination data and mitigates hesitancy and negative influences often associated with mass vaccination campaigns.

Generally, the HCD framework effectively captured the quantitative house-to-house vaccine mobilization data and qualitative data on the challenges and achievements. It guided the determination of community-specific solutions to bridge the zero-dose gap and persistent vaccination defaulting among the under-fives in the study area. This study observed that the majority of participants (council and local community leaders, health workers, community health workers, and grassroots communities) held positive views of the HCD framework for employing community-based solutions to address vaccination challenges among under-fives and bridge the zero-dose and vaccination defaulting gaps in the study area. This framework can be pre-tested in other districts of Tanzania to determine its efficacy in eradicating the country’s zero-dose gap and under-vaccination of under-fives.

4.1. Lessons Learnt

The study demonstrated the transformative impact of engaging community members in every stage of the design and implementation process via co-creation workshops to address their challenges. Data-driven strategic advocacy and the involvement of trusted community members and leaders led to significant outcomes, including providing vaccination services to 131,088 families (83%). This effort reached 387 children with zero doses out of 2550 and identified many defaulters (9899 out of 1753). The success of this approach demonstrated the potential benefits of applying HCD innovation to public health issues, ensuring that the interventions were grounded in the realities and needs of the target population. The implementation team recommended extending this model to different regions and globally and integrating it with training institutions to ensure formalization and local sustainability.

4.2. Limitations of the Study

The study provides valuable insights into using an HCD approach to address vaccine hesitancy and increase uptake among under-five children. However, it was conducted in a single district. The Ilala district may not represent the entire country, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other regions with different cultural, economic, and healthcare dynamics. The insights and interventions developed in Ilala may not directly apply to rural or more socio-economically disadvantaged regions, which might face unique challenges in vaccination uptake. Additionally, the study focused primarily on stakeholders involved in child immunization, such as caregivers, CHWs, and HCWs. However, broader systemic challenges, such as supply chain issues, vaccine storage, and distribution, were not deeply examined. These factors could influence vaccine availability and accessibility, impacting the overall success of the interventions.

4.3. Recommendations

Future research should expand on these findings by conducting similar studies in diverse settings and incorporating broader factors influencing immunization coverage. The Ministry of Health and relevant stakeholders should institutionalize HCD as a core component of the immunization strategy. HCD should be used beyond immunization efforts. Scaling the use of HCD across regions will allow for identifying more nuanced community-specific challenges and co-creating tailored solutions to ensure formalization and local sustainability.