As Earth and Mars orbit the Sun, they pull on each other gravitationally, causing their paths to stretch and relax in a cycle that repeats roughly every 2.4 million years. These subtle orbital shifts change how close the planets approach the Sun, which in turn can alter their long-term climate patterns.

New research shows that the Mars–Earth cycle once had a 1.6-million-year cycle that coincided with major climate swings. The work was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

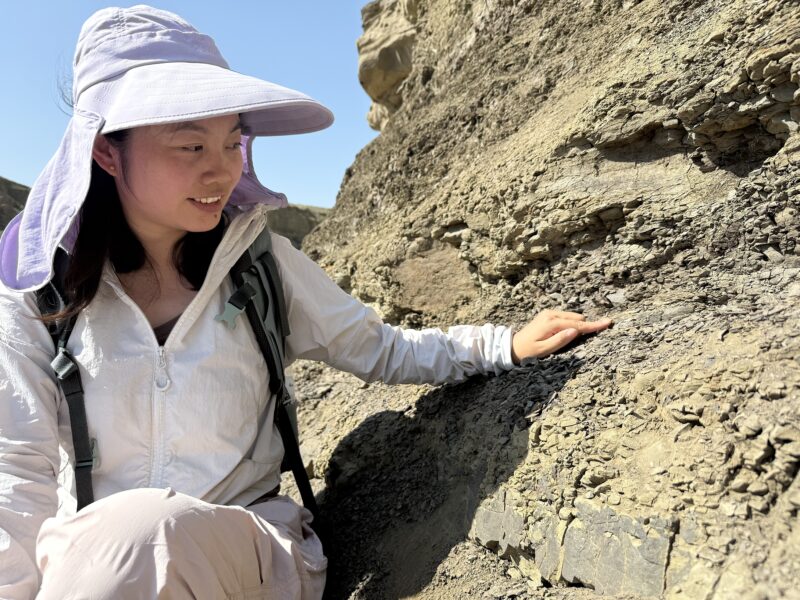

The study was led by Yanan Fang of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Paul Olsen of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, which is part of the Columbia Climate School.

The researchers found geologic evidence for the shorter 1.6-million-year rhythm preserved in Jurassic lake sediments of the Sangonghe Formation in northwestern China. They measured signals lined up to form three complete 1.6-million-year “beats” centered around 183 million years ago. One beat aligns with the Jenkyns Event, when huge lava eruptions in present-day South Africa briefly but sharply warmed the planet via a massive release of volcanic CO2.

“The implication is that the co-occurrence of these two independent events may have amplified their climate impact, although this remains to be fully explored,” says Olsen.

Another key outcome of their study concerns how far back scientists can reconstruct planetary orbits. Until now, orbital calculations were reliable only to about 60 million years ago; beyond that, chaotic interactions among the planetary bodies makes reconstructions unreliable.

Fang and Olsen’s new geological record, combined with older datasets, pushes that boundary about 120 million years deeper into the past, and confirms that the length of the Mars-Earth cycle can change markedly over geologic time, due to solar system chaos.

For media inquiries, please contact press@climate.columbia.edu.

Source link

Francesco Fiondella news.climate.columbia.edu