4. Discussion

The case series presented here shows for the first time that asymptomatic pregnant women with mild right ventricular dysfunction after repaired ToF show abnormal venous Doppler blood flow waves in the liver and kidneys. These waveforms are very similar to the patterns seen in women with preeclampsia. This observation supports the hypothesis that venous congestion may occur in pregnant women, even when RV dysfunction is still pre-symptomatic. This pathway offers a clue into better understanding the increased risk for preeclampsia in women with pre-conceptional right ventricular dysfunction, and—more generally—into explaining the preeclampsia-related maternal organ dysfunctions.

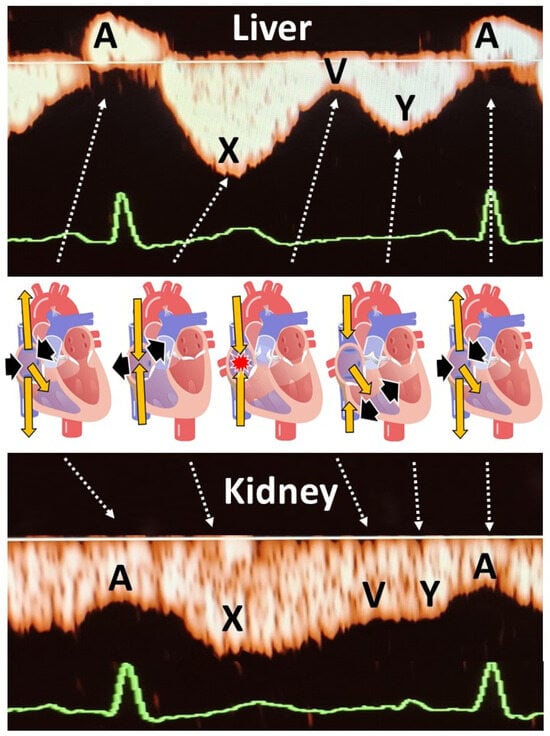

As shown in

Figure 2, second trimester hepatic and renal venous Doppler flow waves in all three cases are clearly different from those observed in the second trimester of uncomplicated pregnancies.

Figure 3A shows the change in venous Doppler flow patterns during the course of a normal pregnancy: in the liver, a dramatic shift is observed from triphasic patterns to flat patterns, and in the kidney, biphasic waves become monophasic. This change can be explained by the physiologic increase in intraabdominal pressure during pregnancy, associated with a rise in intravascular volume and a reduction in vascular tone [

15,

16]. The normal gestational changes in venous Doppler flow waves also occur in women with chronic or pregnancy-induced hypertension, but not in women with preeclampsia [

15]. As shown in

Figure 3A, hepatic venous Doppler waves in preeclampsia are tri- or tetra-phasic, and those in the kidneys show sharp reduction in A-wave velocity as a result of retrograde rebound of right atrium contraction. One of our three pregnant women was diagnosed with intrauterine growth restriction, and none of them had preeclampsia. Despite this, they all showed (1) increased venous impedance index, (2) decreased venous pulse transit time and (3) discontinuous diastolic blood flow patterns (

Table 2,

Figure 2). In non-pregnant conditions, a raised venous impedance index is known to be associated with reduced RV compliance and elevated RV end-diastolic pressure [

17]. In studies on patients with heart failure, this discontinuous renal venous flow is interpreted as a result of intravascular volume expansion and intermittent volume stasis with hampered drainage of venous blood from the internal organs [

18,

19]. The women in our case series all had increased intravascular volume as a result of physiological pregnancy-related volume expansion. Our observations demonstrate that this volume expansion, in association with asymptomatic right ventricular dysfunction, also presents with tri- to tetra-phasic hepatic Doppler waveforms and discontinuous renal venous flow. The relevance of this observation is that these abnormal venous Doppler flow patterns are considered early signs of hepatic and renal congestion [

18,

19]. Venous congestion is responsible for gradual deterioration in organ dysfunction and eventually organ failure, as is known to occur in acute heart failure and in cardiorenal, cardiohepatic and intraabdominal compartment syndromes [

20,

21,

22,

23]. As compared to normal pregnancy, right ventricular dysfunction and higher right ventricle systolic pressures with reduced longitudinal strain are reported in women with preeclampsia [

24,

25,

26]. A direct link between these cardiac features and venous hemodynamics and/or organ congestion have not yet been reported. Our case series shows that right ventricular dysfunction indeed is associated with abnormal venous Doppler flow patterns, and this enhances the vulnerability to organ congestion and dysfunction [

20,

27,

28]. Symptoms of organ dysfunction and abnormal venous Doppler waveforms distinguish preeclampsia from chronic and pregnancy-induced hypertension [

15]. As such, our observation that right ventricular dysfunction is associated with abnormal venous hemodynamics and with an increased risk for preeclampsia is a clinical model that helps explain and understand the symptoms of organ dysfunction in preeclampsia.

Ever since the last decades of the previous century, the etiology of preeclampsia has been linked to a process of abnormal placentation in early pregnancy [

29]. Shallow invasion of the spiral arteries by trophoblast cells is responsible for an inadequate perfusion of the intervillous space, insufficient to meet the needs of the growing conceptus. This causes a state of chronic hypoxia at the level of the placenta, with release of mediators of oxidative stress, systemic inflammation and endothelium activation in the maternal circulation, eventually causing the gestational syndrome named preeclampsia [

30]. More recently, however, this theory has been expanded for several reasons. The histologic features of abnormal placentation are not pathognomonic for preeclampsia, as they are also found in the placentas of uncomplicated pregnancies and are often absent in placentas of patients with preeclampsia [

31]. Clinical observations merely support abnormal uteroplacental perfusion as a consequence, rather than as a cause, of abnormal maternal circulatory function [

32]. An imbalance between cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance, already present before conception, is shown to predispose to gestational complications as preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction [

33,

34]. Our research group also observed a higher incidence of preeclampsia in pregnant women with congenital heart disease, specifically when right ventricular dysfunction is present [

11,

35]. This raises the question whether abnormal placentation may be linked to a process of backward insufficiency of the maternal circulation via a pathway of venous hemodynamic dysfunction and congestion. The case series presented here is in line with this view and is supported by the observation of peri-implantation trophoblast invasion of maternal veins as early as a month before spiral artery patency [

36,

37]. Whereas during the first month after embryo implantation, the lumen of the spiral arteries is blocked by trophoblast plugs, the decidual veins remain patent while they are invaded by trophoblasts [

38]. This serves a direct and open communication canal between conceptus and mother already from the very first stages of implantation: extracellular trophoblast vesicles and placental microRNAs are demonstrable in the maternal serum as early as 6 weeks, whereas spiral arteries only become patent at around 8–10 weeks [

39,

40]. It is likely that abnormal maternal venous hemodynamics at this stage may predispose to an abnormal maternal response to trophoblast signaling, with inadequate installation of gestational adaptations of the maternal circulation that can have important clinical repercussions at more advanced stages of pregnancy. The direct link between abnormal venous hemodynamics and congestion during the process of embryo implantation and placentation is to be evaluated in future research.

Limitations

The inclusion period was during the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore inclusions and data collection were limited. However, since this pilot is an exploratory study, we decided to write down our first three cases, as they all showed abnormal venous flow associated with pre-existing right ventricular dysfunction. Further studies are required to assess the clinical value of hepatic and renal vein examination during pregnancy.