1. Introduction

A bazaar is a multifunctional public space that plays a crucial role in the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of urban life [

1]. It serves not only as a venue for commodity trading but also fulfills broader social functions such as cultural inheritance, information dissemination, spiritual entertainment, and social interaction [

2]. Serving as a central hub of the ancient Silk Road and the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, bazaars embody traditional architectural heritage extensively found throughout Central Asia and Xinjiang, China [

3]. The bazaar has transcended its role as merely a market to become an integral component of social and economic life in Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, effectively becoming a true “cultural landmark” [

4]. The unique social, economic, and cultural contexts of Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, have endowed their bazaars with distinct characteristics.

The bazaar possesses a profound historical heritage and unique spatial value [

5], facilitating cohesion between various urban and rural areas [

6]. It plays a significant role in the social and cultural framework [

7]. The integration of the bazaar’s aesthetic, historical, and cultural values not only engenders a sense of place [

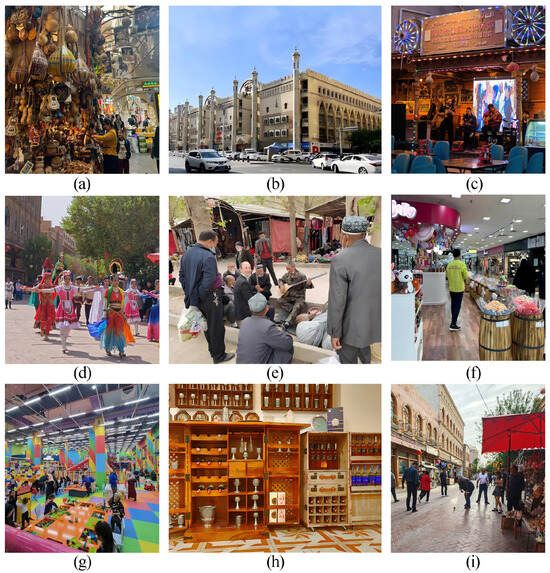

8] but also fosters a deep attachment among its inhabitants to this space. The live view of the bazaar presented in

Figure 1 elucidates its structure and functionality. However, with the advent of modernization, traditional bazaars encounter numerous challenges and impacts [

9]. Traditional bazaars experience pressures from dwindling vitality and face social exclusion driven by spatial delineation [

10,

11]. This dual dilemma renders traditional bazaars particularly susceptible to modernization, compromising their ability to manifest the significance and value of their architectural heritage [

12]. The bazaar is actively seeking new opportunities for transformation and enhancement to rejuvenate its vitality and vigor.

Bazaars serve as vibrant hubs for exploring diverse facets of civilization including architecture, art, economy, culture, and education, all of which influence the bazaar [

13]. The environmental quality directly influences the bazaar’s attractiveness [

14,

15]. As centers of commodity trade, bazaars are crucial spaces for community interaction. Effective spatial design enhances both customer mobility and security, and fosters a sense of participation and community cohesion among residents [

16,

17]. High environmental quality facilitates communication among customers and between vendors and customers, improving usability and thereby boosting the bazaar’s image, competitiveness, and economic vitality [

18,

19]. However, environmental enhancements and spatial optimizations have their limitations. While environmental improvements can quickly enhance a market’s appearance, they may not sustain long-term customer loyalty and attractiveness [

20]. Excessive focus on physical environment improvements can overshadow the cultural essence and uniqueness of the bazaar, leading to homogenization. Moreover, continuous investment is required for environmental maintenance and optimization. Without effective management, resource conservation may be compromised, hindering sustainable development.

The economic environment is crucial for boosting the competitiveness of bazaars [

21]. Optimizing the economic structure promotes diversification of goods and services, thereby increasing the attractiveness of bazaars in a varied market [

22]. A favorable economic environment fosters consumption growth and enhances market traffic and turnover, while stable prices and quality services directly impact customer consumption choices [

23]. Encouraging innovation among traders, supporting the development of local specialty brands, and launching consumer-oriented products can enhance the added value and market recognition of goods, improving the bazaar’s overall image through brand marketing [

24]. The economic impact is limited by short-term interests. For example, vendors might prioritize sales volume over the quality and cultural depth of goods, thereby reducing customer trust and satisfaction [

25]. Overemphasis on economic benefits can lead to the homogenization of goods and services, causing the market to lose its distinct characteristics. Furthermore, if economic activities neglect social responsibility, it could disconnect the market from the community, weakening the consumer base [

26].

Culture plays a pivotal role in the sustainable development of bazaars. Cultural spaces serve as venues for both popular and traditional activities [

27], encompassing material, spiritual, and social dimensions [

28]. As cities evolve, buildings with a single function increasingly fail to meet the complex demands of contemporary society [

29]. Introducing cultural spaces can enhance the multifunctional integration of architecture [

30], merging cultural, commercial, leisure, and entertainment elements. This integration boosts not only the structure’s appeal and competitiveness but also invigorates urban and rural vitality, elevates residents’ quality of life, and bolsters cultural identity and pride [

31]. Bazaars represent a distinct architectural and cultural space within the urban and rural fabric [

32]. As spiritual needs evolve, the cultural and artistic roles within bazaars are becoming increasingly vital. Combining these with cultural spaces can transform and enhance bazaars, promoting social interaction and rejuvenating their appeal and vitality [

33]. While environmental enhancement and economic optimization positively impact bazaar transformations, reliance solely on these factors may increase vulnerability to external shocks. Therefore, culture should be central in transforming and upgrading bazaars. It not only defines their uniqueness and allure but also embeds deep cultural heritage and community cohesion, enhancing resilience during adversities and supporting long-term sustainable development.

Research on bazaars in architectural design primarily addresses the design of urban spaces within bazaars and their sustainable development. Most urban design studies highlight the integral role of bazaars in urban planning. V Mirzaei underscores the need for spatial continuity in bazaars, adhering to hierarchical principles to strengthen the connections between architectural and urban elements, thus fostering a coherent urban space [

34]. H. Sobouti and P. Alavi propose using bazaars as centers for enhancing social interactions, creating sustainable social spaces that contribute to the development of sustainable cities, both socially and economically [

35]. Mohammadreza Pourjafar, employing a historical interpretation approach, discovered that bazaars foster cohesion among various city parts, connecting key urban functions and playing a significant role in the city’s social and cultural fabric, thereby uniting its citizens [

36]. Numerous scholars have identified dilemmas that bazaars face amid urban renewal, prompting investigations into the causes of these dilemmas and strategies for revitalization. BA Kaveh and KR Reihaneh employed spatial syntax to analyze both the bazaar and Tehran shopping centers, concluding that while shopping centers satisfy economic needs, they cannot replace the multifunctional role of bazaars [

37]. ÖZLEM ÖZ and MINE EDER explore the transformation of the bazaar alongside competing urban spaces [

11]. They contend that urban regeneration and modernization efforts have subjected the bazaar to dual pressures: the commodification of public land and the imposition of spatially defined social exclusion. The bazaar must successfully transform to reclaim public space and foster urban socialization. Halleh Nejadriahi and Mukaddes Fasli assessed the sustainability of Tajrish Bazaar using the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), a multi-criteria decision-making tool that incorporates environmental, social, and economic dimensions to address complex problems in sustainable development. The analysis revealed that the social dimension was the most sustainable, followed by economic and environmental aspects [

38]. Lak, Azadeh, et al. proposed a novel methodology for studying the morphology of Iranian bazaars by applying urban space design theory to the Shiraz and Kerman Bazaars [

39]. Mahmoud Ouria applied a four-dimensional sustainability model to examine the sustainable attributes of the Tabriz Grand Bazaar, analyzing its correlation with environmental satisfaction and identifying historical and vernacular architecture as key strengths [

40]. Asif Iqbal and colleagues compared user preferences for shopping malls and bazaars to elucidate the causes behind the marginalization of bazaars in urban development [

41]. I Kiumars and BO Arman investigated structural changes in a Kermanshah City Bazaar and the influencing factors, utilizing field surveys and map comparisons [

42]. Rana Najjari Nabi and colleagues employed a phenomenological approach to detail the physical, functional, and semantic variations within the bazaar, proposing strategies to maintain spatial authenticity and enhance its identity [

43].

This study investigates strategies for effectively leveraging cultural spaces to transform and enhance the bazaar, thereby promoting the sustainable development of its architectural heritage. The focus of this research is on preserving and leveraging the socio-cultural values of traditional bazaars within urban settings to ensure their vitality and adaptability in contemporary society. While research on bazaars has expanded recently, concentrating primarily on their urban spatial roles, structural changes, and related influencing factors, there remains a scarcity of specific studies addressing how to harness the cultural strengths of bazaars to unlock their potential. Moreover, the traditions, customs, and preferences of individuals contribute to unique social, economic, and cultural patterns within the bazaar [

44]. However, the literature lacks comprehensive analyses of users’ subjective experiences and their cultural and spatial preferences. These observations indicate that, despite the critical socio-cultural roles of the bazaar in urban contexts, more systematic research is required to guide its transformation and upgrading, particularly concerning the practical integration of cultural spaces within the bazaar.

To fill this research gap, this paper selects bazaar cultural spaces in Central Asia and China as comparative cases, and through field research, cross-analysis method and narrative preference method, it profoundly explores the commonalities and differences in the development status and user behaviors of bazaar cultural spaces in the two places and proposes targeted transformation and upgrading strategies. The cross-analysis method [

45] compares the relationship between different variables. It can explore in depth the multiple factors affecting specific behaviors, qualitatively compare the impact of each variable on user behavior, and thus identify how the cultural space affects the usage patterns of the bazaar. The narrative preference method [

46,

47], on the other hand, allows subjects to express preferences in the face of a virtual object through an experimental design, which, combined with a discrete choice model to estimate the parameters, can capture users’ emotional responses and preference profiles and provide empirical support. By combining these three methods, the study will integrate qualitative and quantitative data to deeply analyze the behavioral tendencies and preferences of users from different cultural backgrounds in bazaars from multiple perspectives and then provide scientific and feasible suggestions and strategies for the sustainable development of the bazaar.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Content and Methodology

This study encompasses several dimensions: initially, a concise comparison of the prevailing conditions of bazaars in Central Asia and China; subsequently, a detailed comparative analysis of the preferred attributes of bazaar cultural spaces in these regions, which includes an overview of their development, user behavior trends, and the extent of user preferences for different types of bazaar cultural spaces; and ultimately, a conclusion alongside a discussion of the challenges and emerging trends in bazaars and bazaar cultural spaces in both locales.

In this paper, we primarily employ the narrative preference method (SP method) for our research. The narrative preference method is a survey and research technique that enables participants to interact with virtual scenarios and express their preferences through a structured experimental design. This method is often integrated with a discrete choice model to estimate parameters. Detailed descriptions of the specific research steps and methodologies will follow.

- (1)

Bazaar status quo comparison stage

This stage involves a comparative analysis of the current state of bazaars using field investigation methods. We conducted preliminary research on 90 bazaars across four Central Asian countries and 160 bazaars in Xinjiang, China. Our focus areas included the count of fixed and temporary stores, main items sold, commercial and non-commercial functions, recent changes in size and area, and the overall business conditions of the bazaars.

- (2)

The stage of comparison of preference characteristics of bazaar cultural space

This stage began with distributing a bazaar cultural space questionnaire to the residents of Central Asia and Xinjiang, China. We employed cross-analysis to compare the developmental profiles of bazaar cultural spaces and behavioral tendencies of users [

48,

49,

50]. Utilizing the collected data, we identified the attributes and levels of bazaar elements. Subsequently, preference experiments were conducted to ascertain regional preferences for types of bazaar cultural spaces. The experimental procedure is outlined below:

The preferability experiment [

51] utilizes a discrete choice model to analyze user preferences for Central Asian and Chinese Bazaars. This model, detailed in references [

52,

53,

54,

55], encompasses eight attribute hierarchy indicatives of residents’ preferences towards bazaar attributes. The model is structured based on the following mathematical expressions:

—different bazaar choice options,

—denotes the utility value of choosing a specific bazaar,

—model parameters to be estimated,

—the commercial size of the bazaar,

—time taken by residents to travel to the bazaar (unit: min),

—different subcategories of the bazaar’s cultural–spatial functions.

Orthogonal experiments were conducted using SPSS 27 software to identify 23 valid attribute combinations for evaluating bazaar selection intentions. These attributes were integrated into a questionnaire targeting residents of Central Asia and Xinjiang. The survey was distributed in both paper and online formats. In total, 115 valid responses were collected from Central Asia, and 489 from Xinjiang, China. After collecting and counting the data, the model will be used to determine the relative importance of each influencing factor, and the parameter fitting of the model will be carried out by Stata 18 statistical software.

The validation experiment was conducted using principles analogous to those of the initial research study, but it incorporated updated attributes and level data pertaining to new bazaar elements. A discrete choice model was developed to depict residents’ preferences for bazaar spaces, featuring 11 attribute levels. This model not only includes six primary functional attributes but also incorporates five additional factors: degree of openness, environmental quality, fees, frequency of activities, and event duration. These factors are vital in shaping preferences for the various sub-functions within the bazaar’s cultural framework. The mathematical expression for the model is as follows:

—different options for the bazaar,

—selecting the utility value of a specified bazaar,

—model parameters to be estimated,

—six sub-functional types of bazaar cultural spaces,

—five attribute indicators that influence preferences.

A new questionnaire containing 49 valid combinations was then designed, resulting in 73 valid questionnaires recovered from Central Asia and 416 valid questionnaires from Xinjiang, China. In the new questionnaire design, instead of considering the size of the bazaar and the time needed to travel to the bazaar, the data were obtained by distributing the questionnaires on-site in typical bazaars at different levels (city, regional, and community). This method effectively solves the previous questionnaire’s problem of difficulty in measuring the impact of different bazaar sizes on residents’ preferences and reduces the possible bias of the public in self-judging bazaar levels.

A redesigned questionnaire featuring 49 valid combinations yielded 73 responses from Central Asia and 416 from Xinjiang, China. In this updated questionnaire, data collection occurred directly at bazaars across varying levels—city, regional, and community—omitting prior considerations of bazaar size and travel time. This approach addresses prior difficulties in assessing the impact of bazaar sizes on resident preferences and mitigates potential biases in the self-assessment of bazaar levels by respondents.

The data from the collected questionnaires were analyzed using Nlogit 4.0 statistical software, yielding standardized fitted results.

2.2. Sources of Research Data

Central Asia and China, regions characterized by extensive bazaars scattered across remote villages and towns, provided the data for this study through field surveys and questionnaires administered in representative bazaars. From October 2023 to April 2024, the research team carried out comprehensive surveys in 31 districts in Kazakhstan, 25 in Uzbekistan, 30 in Kyrgyzstan, and 4 in Tajikistan, covering a total of 90 bazaars. In China, bazaars are predominantly located in the Xinjiang region. From June 2019 to August 2020, the research team conducted exhaustive studies on 160 bazaars varying in size across 106 counties in Xinjiang. Concurrently, multiple questionnaires were administered to residents of Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, including the Bazaar Basic Research Questionnaire, the Bazaar Cultural Space Questionnaire, and the Questionnaire on Residents’ Willingness to Choose Bazaars.

Owing to the considerable temporal gap between the research conducted in Central Asia and that in China, the team undertook a targeted review of Chinese bazaars from March to June 2024. This involved sampling 56 bazaars of varying sizes in the Urumqi, Turpan, Yili, Hotan, and Kashgar regions of Xinjiang. Additionally, spatial questionnaires and Bazaar Choice Intention Questionnaires were distributed to the residents.

3. Findings

3.1. Comparison of the Current Status of the Bazaar

The comparative analysis of bazaars in Central Asia and China centers on several dimensions: the number of fixed and temporary stores, the range of products sold, commercial and non-commercial functions, changes in size and area over recent years, and the overall business climate.

Both Central Asian and Xinjiang Chinese bazaars feature a mix of fixed and temporary stores. In contrast, Central Asian bazaars predominantly comprise fixed stores, averaging 369 per bazaar, double the number of temporary stores. Xinjiang bazaars in China blend fixed stores with temporary stalls, notably those operating only one or two days a week, such as the Friday Bazaar in Xiaoyingpan, Bole City, Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, which heavily depends on temporary stalls.

Both bazaars cater to local needs, primarily selling daily necessities, food ingredients, medicinal herbs, clothing, decorations, handicrafts, electrical equipment, building materials, and home furnishings. Commercial functions such as retail and catering dominate both Central Asian and Xinjiang bazaars, with the former more focused on wholesale operations and the latter integrating commercial activities with tourism services.

Both bazaars reflect local characteristics. However, Central Asian bazaars focus more on form, featuring straightforward regional displays like song and dance performances and visual exhibitions, with limited interactive participation. In contrast, Chinese bazaars emphasize deeper engagement through interactive experiences.

Central Asian bazaars frequently host educational and training activities, sports competitions, and entertainment, whereas art performances and medical services are less common. Conversely, Xinjiang bazaars in China feature a balanced distribution of functions, including entertainment, exhibitions, art performances, and public facilities. However, in terms of the bazaar as a whole, there are fewer cultural spaces in the bazaars of both places.

Recent years have seen minimal changes in the scale of Central Asian and Chinese Xinjiang bazaars, likely due to force majeure events and operational challenges. Only a few bazaars in Central Asia exhibit a slight growth trend, whereas some in China have seen reduced functionality and scale.

3.2. Comparison of Bazaar Cultural Spatial Preferences

In this phase of the research, a questionnaire focusing on bazaar cultural spaces was distributed to residents of Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, to explore the developmental trends of these spaces and the behavioral tendencies of the users in both regions. Subsequently, a discrete choice model was developed using the collected data to evaluate the significance of various attributes and to delineate the preferences of residents in both regions for different types of bazaar cultural spaces.

3.2.1. Comparative Overview of the Development of Cultural Spaces in the Bazaar

The analysis of the integration of the bazaar into the daily lives of residents, its connectivity to the public transportation system, accessibility, openness, and the typological distribution of bazaar cultural spaces, unveils the current state of their development in Central Asia and Xinjiang, China.

The bazaars in both Central Asia and China exhibit only a moderate connection to daily life, as indicated by most respondents who rate the level of integration as average, with a notable minority perceiving it as weak or negligible.

Figure 2 illustrates a cross-reference of the connection intensity between bazaars in Central Asia and those in Xinjiang, China, with regional distribution. From a regional analysis, it is evident that in both territories, underdeveloped areas, particularly rural zones, demonstrate a stronger reliance on bazaars. Conversely, bazaars in urban centers have the weakest link to daily life, likely due to the varied shopping alternatives available to city dwellers. Upon comparing the two regions, the bazaars in China’s Xinjiang province show a closer integration with daily life than those in Central Asia. However, the bazaars in the rural areas of Xinjiang are less integral to daily life compared to those in Central Asia, possibly due to the impacts of China’s rural revitalization and the proliferation of e-commerce, which have provided rural inhabitants with alternative shopping methods and reduced their dependence on bazaars.

- 2.

Closeness of the Bazaar to Public Transportation:

The proximity of the bazaar to public transportation is evaluated based on two criteria: first, the residents’ preferred mode of transportation to the bazaar, and second, the walking distance from the nearest public transportation station to the bazaar. According to the data in

Figure 3, walking and private vehicles are the predominant transportation methods used by residents of both regions to access the bazaar. The data further show that only a small fraction of residents opt for public transportation in both regions. However, the proportion of bazaar-goers in Xinjiang, China, utilizing public transportation is slightly greater than in Central Asia, though it remains below one-fifth of the total number of visitors. Among those who utilize public transportation, a majority of respondents in Xinjiang, China, and Central Asia reported that the walk from the nearest public transport stop to the bazaar takes less than 10 min. Slightly fewer than one-sixth of the individuals in Xinjiang, China, reported a walking time exceeding 10 min from the public transport stop to the bazaar, compared to one-fifth in Central Asia. The data suggest that bazaars in China have a slightly stronger connection to public transportation, indicating that both regions’ bazaars were designed with accessibility via public transport as a priority. Nevertheless, there is a need to enhance integration with the public transportation systems in both regions.

- 3.

Bazaar accessibility and openness:

Greater regional development correlates with denser bazaar distribution, shorter resident travel distances, and a greater diversity of transportation modes. Residents of Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, are considered in a cross-comparison of bazaar consumption times, as depicted in

Figure 4a. Across these regions, small to medium-sized cities demonstrate the highest accessibility levels, while rural areas exhibit the lowest. This pattern suggests that urban traffic congestion extends travel times for residents and diminishes overall accessibility. Comparative data reveal that bazaar accessibility in Xinjiang, China, surpasses that in Central Asia, particularly in rural Chinese areas. Regarding openness,

Figure 4b illustrates that approximately four-fifths of Central Asian residents and two-thirds of residents in Xinjiang, China, expect all-weather access to public spaces within bazaars. However, fewer than one-tenth of Central Asian bazaars and less than one-sixth of bazaars in Xinjiang, China, offer all-weather access to their public spaces. This indicates a significant mismatch between resident needs and the current availability of public spaces and opening hours in both Central Asian and Xinjiang Chinese bazaars, pointing to a general inadequacy in these provisions.

- 4.

The current distribution of the types of cultural spaces in the bazaar:

When comparing the current distribution of cultural space types in the Central Asian and Chinese bazaars (see

Figure 5), it is observed that in the Central Asian bazaars, educational services predominate, followed by exposition, production, folklore, and performance-viewing services. In the Xinjiang bazaars, however, exposition services lead, followed by performance-viewing, educational, production, and folklore services. The distribution of cultural space types across both regions is uneven, particularly in Central Asian bazaars, where educational functions constitute nearly half of all spaces. Conversely, performance-viewing spaces represent a mere 8.97% of the total.

3.2.2. Comparison of Behavioral Preferences of Users of Bazaar Cultural Spaces

The analysis of bazaar user behavioral preferences encompasses four dimensions: purpose and behavior, visit frequency, length of stay, and influencing factors.

Residents of China and Central Asia visit bazaars for broadly similar purposes, as shown in

Figure 6, with most going for entertainment, some to socialize, and a few for residence and work. The behavior of the residents of these two areas entering the bazaar is also similar, with most residents going to the bazaar to shop and eat, others going to hang out and meet with friends, and only a few going to the bazaar for work and residence. Visiting behavior aligns closely with the residents’ objectives for visiting the bazaar. It is worth noting that some of the residents of the visiting Central Asian and Chinese bazaars are involved in cultural activities, which indicates that although the current function of the bazaar is mostly centered on economic activities, cultural elements are gradually being integrated into the function of the bazaar. The potential environmental and social value of these bazaars should be further emphasized and developed.

Frequency of visits: Both Central Asian and Xinjiang bazaars experience low visitation rates, as illustrated in

Figure 7. Over half of the Central Asian residents rarely visit the bazaars, a situation exacerbated in Xinjiang, where nearly four-fifths of Xinjiang residents hardly ever go to the bazaars, while the majority of those who do go to the bazaars visit them once a month. The lack of appeal in the commodities and cultural spaces of these bazaars contributes to their infrequent visitation. However, a small number of respondents in both regions visit the bazaar almost daily for work, residence, dining, or recreation, indicating that the bazaar’s multifunctionality could enhance visit frequency. Further analysis correlates shorter travel times to the bazaar with increased visit frequency, revealing a significant positive relationship between accessibility and frequency of visits. The more mixed the functions of the bazaar, the higher the accessibility and the higher the frequency of visits.

Length of stay: Data from

Figure 8 indicates that most respondents from Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, spend between 0.5 to 3 h at the bazaar. Particularly, 64.55% of Central Asian and 78.84% of Xinjiang respondents report staying within this time frame, with Xinjiang attendees typically staying longer. Further analysis reveals a direct link between the bazaar’s openness and length of stay; residents favoring access to public spaces generally stay longer, often exceeding three hours.

Factors affecting willingness to visit: A comparison of the statistical data affecting willingness to visit the bazaar in Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, is shown in

Figure 9. The principal factors influencing Central Asian residents’ choice of bazaar are environmental quality, ease of access, and business format. Similarly, Xinjiang residents prioritize ease of access, environmental quality, and business format, with little variation in their importance scores. Accessibility, business diversity, and environmental quality are key determinants of visitation willingness. Specifically, environmental quality is paramount in Central Asia, whereas accessibility is crucial in Xinjiang.

- 2.

Analysis of behavioral preferences of users of the bazaar cultural space

Residents of Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, generally favor the integration of cultural spaces within their bazaars. As shown in

Figure 10, there is a general willingness among these residents to visit more frequently and extend their stay at the bazaar.

Figure 11 reveals that the choice to frequent bazaar cultural spaces is driven by their interesting content, the openness of the venue, a comfortable environment, and freedom of choice. The integration of cultural spaces not only increases residents’ willingness to visit and duration of stay but also enhances the influence and competitiveness of the bazaar’s cultural offerings by offering advantages over traditional venues. This integration fosters a synergistic relationship marked by mutual benefit. Preferences vary regionally; Central Asian residents are drawn to bazaars with compelling content, whereas those in Xinjiang, China, favor those offering more open spaces.

3.2.3. Comparison of Bazaar Cultural Space Type Preferences

Preferences for cultural spatial types in Central Asian and Chinese bazaars were quantitatively analyzed using preference experiments. The resulting data were then compared to elucidate regional differences in spatial preferences among residents. The results of the preference test fit are detailed in

Table 1.

The goodness-of-fit values for the validation tests registered at 0.15, 0.15, and 0.18, respectively. Although these values indicate a modest fit, the results are deemed usable. Comparing the first model result folds with the second model mean result folds (

Figure 12), the two results of the Central Asia Bazaar differ only in the order of weights of convenience services and healthcare. The two results of the Xinjiang China Bazaar differ only in the order of weights of convenience services and education and training. Despite these differences, the experiments in Central Asia and Xinjiang, China, display broadly similar trends in weighting for each sub-function, suggesting mutual corroboration.

Based on the data in

Table 1 and

Figure 11 the following results can be obtained:

In Central Asia, residents’ preferences for cultural space functions within the bazaar rank as follows: Culture and Arts > Plaza and Green > Leisure and Recreation > Education and Training > Medical and Healthcare > Citizen Services. In Xinjiang, China, the preferences for cultural space functions within the bazaar are ordered as: Culture and Arts > Leisure and Recreation > Square and Green > Education and Training > Civic Services > Medical and Healthcare. The function of culture and arts is the most favored cultural space among residents in both regions.

The negative coefficients associated with travel time and the size of the bazaar suggest that, ceteris paribus, residents prefer bazaars that are closer and smaller.

3.3. Second Survey of Bazaar Cultural Space in China

The research team conducts a second survey of the Chinese region regarding the current situation of the bazaar and the preferences of its cultural space.

3.3.1. Current Situation of Chinese Bazaars in the Second Survey

The second survey’s results indicate minimal changes in the fundamental aspects of Chinese bazaars, including the count of permanent and temporary stores, the primary goods for sale, the inclusion of commercial and non-commercial functions, the area size of the bazaar, and the overall commercial environment. Only a slight increase in the number of temporary stalls and recreational space in some of the bazaars, while other overall changes were not significant.

3.3.2. Preferences of Chinese Bazaar Cultural Spaces in the Second Survey

The second survey’s results on the cultural space preferability of Chinese bazaars are compared with the first survey’s results. The data in

Figure 13 show that the two surveys’ results on Chinese bazaars have only minor data fluctuations, and the overall results have not changed much. Consequently, the comparative analysis of cultural spaces in Central Asia and the Chinese bazaar conducted in this paper holds validity.