3.1. Components of Early Warning Systems

EWSs currently have a wide range of applications. They are used to warn against crisis events of various types. Since crisis management is a multidisciplinary field, such systems require knowledge from various disciplines, which should be integrated into the general crisis management framework, under which the need for EWSs also falls. As Zhou et al. [

22] mentioned, EWSs rely on a wide sensor network, simulation tools, and decision-making systems. The foundation of every system lies in data collection, which is then analysed and assessed. For natural crisis events, this primarily involves physical parameters, as well as chemical ones, which influence the occurrence of natural hazard.

The infrastructure of EWSs relies on data collection using sensors or satellite technologies. The systems consist of numerous parts, and various technological devices and often people are integrated into them. An EWS could be defined as a complex system, consisting of data sources, data transmission, data storage, data assessment and evaluation, and the distribution of information about specific impending hazards through technical communication means. The basic difference between EWSs and MHEWSs is the complexity of MHEWSs, which functions for multiple natural hazards; however, the term EWS is also often used in this context.

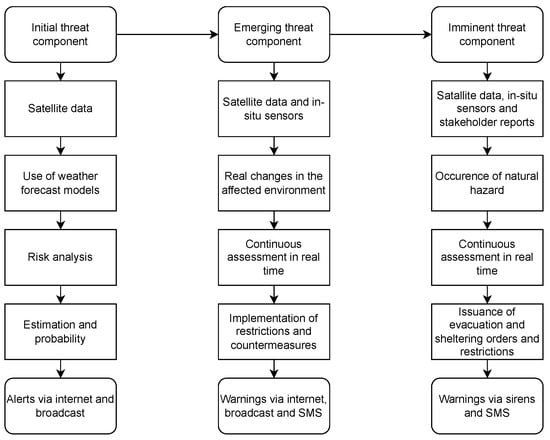

The basic data sources for warning systems are generally sensors. However, in addition to sensors, more complex satellite technologies and satellites should be implemented. The systems should be as comprehensive as possible since their role should not only be to warn about imminent threats in real time, but they should also provide information for early warnings and alerts about the potential development of crisis events. From the perspective of the importance of threat information, EWSs and MHEWSs could be divided into three components based on the timeline in which they operate and the information they distribute:

Initial threat component;

Emerging threat component;

Imminent threat component.

The first component should be the initial threat component. Within this component, the system should record the initial signs of a crisis event, respectively, the potential for its occurrence, the probability of its occurrence, including the likely affected area. These are initial data, which we already acquire today and can work with effectively. These data are used in weather forecasts. This primarily involves the use of forecast models, which mainly stem from satellite images and satellites.

These satellites can quantify physical geographic phenomena associated with the movements of the earth’s surface (earthquakes, mass movements), water (floods, tsunamis, storms), and fires. These satellites contain different kinds of sensors that are used for the remote sensing of natural hazards over a number of spatial and temporal scales [

41]. However, empirical data also play a very important role here, from which the most probable effects of crisis events are modelled [

42].

The greatest use of these data sources lies in estimating precipitation, temperature, and wind, which reflect the key characteristics of natural crisis phenomena. They are particularly significant in predicting hurricanes, floods, droughts, extreme temperatures, strong winds, and storms. Additionally, they play a crucial role in assessing fire risk. These insights provide crisis management with initial information and the opportunity to prepare for potential crisis events. The information is primarily used in the crisis management cycle during the prevention phase [

43].

On a global scale, the technological infrastructure for this already exists; however, the main reason for the lack of implementation in crisis management is not the unavailability of solutions but rather the lack of awareness among relevant stakeholders and authorised management regarding their existence or potential [

44]. Meteorological entities generally have access to this information. However, a challenge may arise from limited access to these technologies and the data they generate for poorer countries that lack the financial resources for their own remote sensing technologies or are not part of larger networks that possess such data. A particular challenge lies in integrating these data into crisis management structures and extracting relevant information from meteorological systems for the needs of crisis management.

Beyond the need for crisis management, this information should also serve the general public, informing them of existing risks that could arise from certain activities, helping them plan accordingly. These insights should be distributed in the form of alerts. At this stage, distribution should occur through crisis management applications, the internet, or broadcast, while critical infrastructure entities should receive alerts via pre-established methods. Other forms of communication to the public are less meaningful at this stage, as this information should be disseminated several days before a potential threat emerge. Additionally, at such an early stage, there is still a degree of uncertainty regarding the development of the situation.

The second component should focus on the initial onset of a natural hazard. This component primarily deals with the actual impact of given influences on a specific area, rather than just the probability of occurrence, as in the first component. At this stage, there is a shift in hydrological, meteorological, or geological conditions in a given area. From a crisis management perspective, this phase involves restricting certain activities that pose a danger or preparing countermeasures. The information provided as an alert is now transited into a warning. It is recommended that warnings at this stage should be issued also via SMS to maximise public awareness of the potential danger [

12,

45].

Since 2018, the European Union has enforced Directive (EU) 2018/1972 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 establishing the European Electronic Communications Code, which mandates that all member states implement an SMS and broadcast-based warning system for designated risk areas [

46]. Such messages should include details about the emerging danger, recommendations for necessary actions, and activities that should be strictly avoided. Additionally, important businesses should be notified, particularly those that may pose a hazard or are classified as high-risk. These include critical infrastructure facilities and enterprises handling hazardous substances.

For the second component, meteorological information from satellites and data from ground-based sensors should be integrated. Real-time data should be used to continuously assess and adjust predictive models, ensuring the most accurate possible estimation of a crisis event’s development.

The third component should account for the actual occurrence of a crisis event and its impact as a direct threat. This is the moment when there is a real risk to life, health, property, or the environment—an imminent threat requiring immediate attention, emergency response, and the implementation of protective measures to mitigate its effects. In this phase, measures such as evacuation, sheltering, or restricted access to affected areas may be enacted.

The goal of the third component is to warn the public of an imminent threat with clear instructions for protection and appropriate action. At this stage, warnings and notifications should be communicated through sirens as well as SMS messages. Crisis event information should be conveyed as clearly and concisely as possible. Public messages must meet certain quality criteria—they must be truthful, timely, and comprehensive [

47]. The information should precisely indicate the type of crisis event, the extent of the threat, the severity level, and the necessary actions to be taken.

EWSs must be comprehensive. All three components should be integrated into a single system within the crisis management structure, ensuring access to up-to-date and relevant information required for decision-making and response. Real-time data sources, particularly sensors and remote sensing technologies, play a crucial role. While a significant amount of data infrastructure already exists, further development is necessary—especially in establishing measuring stations equipped with sensors to monitor parameters that trigger crisis events, as well as to measure their actual manifestations.

Figure 1 presents a model of an EWS based on three components.

For crisis management, receiving, analysing, and modelling these data are critical. Emphasis should be placed on a unified information system that not only displays all relevant information but also evaluates all the data using machine learning methods or artificial intelligence, with direct capabilities for issuing alerts and warnings.

3.2. The Importance of Sensors in Early Warning Systems

Sensors play a crucial role in EWSs. They collect real-time data, which are extracted into databases and can be integrated into various systems, including the Geographic Information System (GIS) [

48]. They are fundamental for data collection to assess crisis events, their severity, or for developing predictive models, as well as for analysing past events and their extent. In addition to real-time data, empirical data are also valuable for evaluating the impact or severity of crisis events. Their role in EWSs within crisis management is particularly significant. Depending on their configuration, sensors detect the presence of input information and its value.

Ideally, information is automatically evaluated using machine learning or artificial intelligence, and warnings are sent to at-risk populations within seconds. This is especially crucial for earthquakes, where machine-based evaluation is essential for applying ground motion prediction equations (GMPEs) [

49]. These equations enable the calculation of the anticipated affected area of an earthquake. One of the most advanced earthquake EWSs is in Japan, where sensors detect P-waves across a wide network. The system then distributes alerts to the affected population a few seconds before the arrival of stronger seismic waves. The system can also estimate the magnitude and intensity of the earthquake [

50].

Sensors are also widely used in flood EWSs. There are several ways to use them effectively, but one of the most critical parameters for flood risk and EWSs is water level height. During rainfall events, river levels rise due to natural runoff from the terrain. The most common cause of flooding is a river overflowing its banks due to intense or prolonged rainfall [

51].

When assessing flood risk, two key indicators are essential for predictive models and evaluating flood severity:

Water level height;

Flow velocity.

Flow velocity or water discharge helps estimate the anticipated water level height in a given section of the river. Using empirical data, it is possible to calculate both discharge and inflow from real-time data. If discharge is lower than inflow, water accumulates, leading to a rise in water levels. The water level height directly reflects the destructive nature of floods and their potential formation [

52,

53].

However, for early warning purposes, real-time data are the most critical. It is essential to integrate meteorological stations and sensor networks into crisis management structures and ensure their continuous evaluation [

54]. By analysing a digital elevation model (DEM), it is possible to identify locations where the riverbed is shallowest and narrowest. When combined with empirical data and rating curves, these models help identify areas where river overflow is most likely. Water level sensors should be installed at these critical locations [

55].

An alert should be sent to at-risk populations when:

Another key parameter is flow velocity, which provides insights into river discharge. If inflow exceeds discharge at certain points, water accumulates, increasing the risk of localised flooding.

These examples illustrate how sensors can be used to monitor crisis event formation. However, their implementation is possible for many other crisis events beyond earthquakes and floods. Selecting appropriate sensors is essential, both for monitoring the factors that trigger crisis events and for detecting the actual manifestation of those events.

3.3. Requirements for Early Warning Systems

EWSs should reflect current requirements for sustainability from the perspective of sustainable development goals [

56], accuracy, integration, and complexity. Ideally, sensors and all necessary components for signal and information distribution should be powered by renewable energy sources. One possible solution is the use of solar panels or wind turbines. These renewable sources have already been applicated in many applications and have proven to be an efficient source of energy [

57,

58].

However, both options present certain disadvantages. Solar panels are highly dependent on direct sunlight and receive only a small amount of energy from diffuse radiation. The biggest challenge arises during prolonged cloudy weather or winter months, when only diffuse solar radiation is available for an extended period. On the other hand, the main drawback of wind turbines is the long-term absence of wind. A suitable solution could be a combination of solar panels and wind turbines with an appropriately oversized 12 V battery. The battery must be capable of ensuring the operation of all components for at least seven days.

It is common for meteorological station components, such as sensors, to be designed for 12 V batteries, eliminating the need for voltage converters. To ensure continuity and availability of information, it would also be advisable to have a backup power source from the grid where feasible and financially viable. Using renewable energy as the primary source meets sustainability requirements.

Ensuring an uninterrupted dataset is one of the key quality parameters for flood prediction. Annual peak flow records are compiled, where possible, from an uninterrupted observation period. However, the periods used to select annual peak flow records may not be the same for all hydrometric stations. According to OTN ŽP 3112-1:03, datasets of annual peak flows must be homogeneous. Homogeneity in this context means that the data must be selected from a period in which there was no significant human-induced influence on the hydrological regime, such as the construction of reservoirs, water diversions, or extensive river modifications [

59].

By centralising multiple sensors in one location, a comprehensive monitoring system can be established. It is important to recognise that in addition to physical and chemical parameters, which ultimately reflect the destructive nature of a crisis event, various other phenomena contribute to the formation of natural hazards. These factors can be classified into:

Primary causes, which directly trigger a crisis event;

Secondary causes, which influence the intensity and extent of the event.

Additionally, other factors may affect the occurrence of a given hazard, such as terrain characteristics, forest cover, sediment accumulation, or infrastructure. Some of these factors are particularly difficult to assess or monitor over time. Even if they are not identified as primary or secondary causes, they may significantly influence the final manifestation of crisis events.

Table 2 presents primary causes of natural hazards, as well as secondary factors that affect their intensity and extent. A categorisation of these causes was conducted to define the fundamental reasons behind their occurrence.

The primary causes of floods are highlighted in a significant review by Abegaz et al. [

51], where it can be observed that floods are most often the result of excessive precipitation, frequently accompanied by storms or hurricanes, snowmelt, and, in coastal areas, high tides. Research by other authors confirms this assumption [

52,

60,

61].

Secondary causes increase the intensity of floods, as they lead to soil saturation with water, reduced evapotranspiration, or high humidity affecting evaporation.

In the case of droughts, the main causes include a lack of precipitation in the affected area, high temperatures leading to increased soil drying, and excessive evapotranspiration [

62,

63,

64]. A lack of groundwater further accelerates evapotranspiration, as does low humidity.

Wildfires, while a natural hazard, are strongly influenced by anthropogenic activity. The key causes therefore include physical parameters that significantly increase the risk of ignition. In this regard, temperature and air humidity play a crucial role [

65,

66,

67].

For landslides, from a climatic perspective, precipitation levels have a major impact. During rainfall events, the soil becomes saturated with water, leading to a rise in groundwater levels and soil moisture. Rainfall therefore reduces embankment stability [

68]. As pointed out by Zhao et al. [

69], in addition to rainfall, internal dynamic factors, such as earthquakes, play a significant role. As noted by Korkmaz [

70], ground shaking and ground failure lead to ground motion, which contributes to the occurrence of earthquakes.

Beyond identifying primary and secondary causes, it is also important to consider the final effect, manifestation. This effect reflects the destructive impact of various hazards, and in the development of an EWS, its monitoring is crucial. Observing these parameters plays the most important role in the response phase of the crisis management cycle. Manifestation refers to the direct impact of a natural hazard, representing its primary consequence upon occurrence. Essentially, it marks the transition of the hazard from a potential threat to an active force with measurable consequences.

Table 3 illustrates the manifestations of natural hazards, which represent the primary danger or sources of risk to the population.

3.4. Flowchart for Early Warning Systems

Based on

Table 2, the primary and secondary causes influencing the occurrence of natural hazards have been identified.

Table 3 further categorises the manifestations of these hazards.

When designing a comprehensive monitoring and early warning system, it is essential to consider not only the causes of these events but also their manifestations, as these are the direct sources of risk. In EWSs, sensors should be used to identify both the causes and consequences of hazards. Therefore, a data flow analysis is necessary.

The diagram follows the initial impact of primary causes, which are continuously monitored by sensors. These data are constantly transmitted to a data centre, where they are analysed. The same applies to secondary causes.

The manifestations of natural hazards represent state variables, they exist at all times, but their values fluctuate. When a hazard occurs, these values change, creating anomalies. Throughout the event, their development is monitored by sensors that collect real-time data, which are then sent to the data centre or database.

Modern EWSs often integrate automated processes, artificial intelligence, and machine learning [

71,

72,

73]. However, human input is still used for data monitoring and analysis in many cases. If an anomaly meets the criteria for activating a warning system, the system is triggered, and an alert or warning is issued. In this case, the final step in the model is the distribution of this information to the affected population. A flowchart of such a system is illustrated in

Figure 2.

However, some data remain static or are difficult to measure—primarily spatial data. This includes factors such as substrate composition, terrain slope, orientation, and land use and land cover, which should be available to crisis management teams for risk assessment [

35].