Three test cases with available measurements from the literature are selected to asses the accuracy of the code. The corresponding primary parameters are reported in

Table 3. It should be noted that, in the results discussion, the specific parameters follow the definitions of the corresponding reference papers. However, to facilitate the comparison among the case studies, the flow coefficient

adopted in

Table 3 is computed equivalently for any geometry and reads as follows:

where

n is the rotational regime,

D is the rotor external diameter, and

Q is the volumetric flow rate.

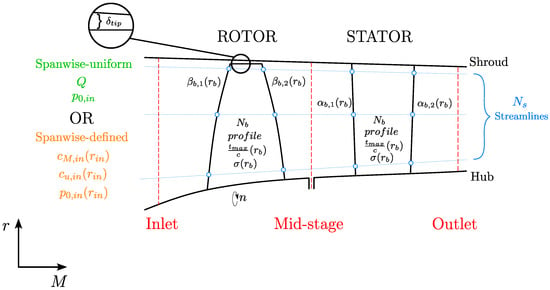

Before analyzing the code performance, the implementation was calibrated comparing empirical model combinations (

Figure 4). Specifically, a sensitivity study was conducted to determine the minimum number of streamlines required to make the results independent of the channel discretisation. This investigation showed that incrementing

above 21 does not provide consistent variation of the predicted statistics (

Figure 4a), and therefore, this quantity was adopted henceforth. Thus, all the computations reach convergence below

on all the residuals within 25 iterations. A typical residuals profile for near-design computations is reported in

Figure 4b.

3.1. NASA Rotor 02

The NASA R02 is a straight-duct rotor intended for initial stages operations, following an inlet inducer. The geometry results from a modification of previous designs [

32,

33] and the blade element measurements were made available in Miller et al. [

13]. The corresponding data are adopted as a reference for both the inflow boundary conditions and the outflow predictions comparison. Six different operating points (configurations 1 to 6) are selected within a range of flow coefficients,

, ranging from

to

. Here, the machine parameter is defined as

, with

denoting the rotor passage cross-sectional area. For this case study, the inflow quantities are provided as radial profiles instead of uniform distributions.

The resulting rotor map is reported in

Figure 5, depicting the work coefficient,

, and the hydraulic efficiency,

, as functions of the flow coefficient. Here, the two parameters are respectively defined as follows:

where the head

is computed as the total pressure (

) jump across the rotor,

is the tip rotor speed, and the ideal head rise is computed as

.

The pressure rise capability trend is in line with the experimental measurements. However, the computed solution exhibits a stable overprediction, inducing a discrepancy with a . However, with marginal improvements, the code portrays lower errors near the design operating conditions. This aspect is further emphasized by the efficiency curves comparison. In fact, from the experiments, the sudden drop of the hydraulic efficiency below the design point, combined with the smooth behavior of the work coefficient, suggests an abrupt increment of the measured torque. Differently, the code tends to smear out highly non-linear effects, recovering a smooth efficiency curve that constantly departs from the test data as the flow coefficient increases. As a result, the prediction error transitions from values below to over .

To investigate local accuracy, the spanwise distributions of meridional and tangential velocities and outflow relative angle are adopted to compare between ARES computations and experiments at both off- (configuration 1,

) and near-design (configuration 5,

) conditions (

Figure 6).

For configuration 1, the tangential velocity distribution exhibits a significant alignment with the test data, except for a marginal discrepancy in the span region between

and

(

Figure 6a). Conversely, the meridional component is stably underpredicted across the entire blade radius, with the major separation observed at mid-channel and the accuracy loss mitigated near the extremes. The mutual behavior of the two velocity components can be analyzed through the relative flow angle distribution (

Figure 6b). The predicted curve is generally in good agreement with measurements, depicting a maximum of

deviation above a span of

. At this location, such overprediction is induced by the underprediction of

, in contrast to the accurate estimate of

. On the other hand, above a span of

, the computed and measured curves tend to realign. This effect results from the underestimation of the tangential component, which is mitigated by a more accurate prediction of the meridional one.

The most accurate efficiency prediction is achieved for flow configuration 5. Since the computed head rise is higher than in the experiments, the low deviation of the efficiency curve depends on the ideal head rise prediction, which is a quantity uniquely determined by velocity components. In fact, the tangential velocity exhibits overprediction across the entire span, with a discrepancy increasing from the hub to shroud, except for end-wall boundary layer effects reducing the computed and tested curves separation (

Figure 6c). The resulting meridional velocity prediction evidently suggests an accuracy improvement, despite a stable underestimation. Similarly to the previous case, the mid-channel solution exhibits higher deviation from the test data. Conversely, the relative flow angle portrays a significant alignment with experimental measurements, with further reduction of the discrepancy, now located near span

(

Figure 6d).

This analysis indicates that pressure and velocity predictions are not directly correlated. In fact, while flow directions were generally aligned with experiments, the pressure field was stably overpredicted.

3.2. HIREP

The HIgh REynolds number Pump (HIREP) facility was adopted to conduct measurements on the flow effects of an IGV installed upstream of a rotor [

25,

26]. Here, the test data between the two blades are retained as inflow boundary conditions, while computations are compared downstream of the rotor. This test case provides insights into the code accuracy, when operated under non-uniform, swirled inflow. An operating map is reconstructed, tracking the variation in the torque coefficient,

, as a function of the flow coefficient,

(

Figure 7), with the former defined as in the reference experiments [

25]:

where

C is the rotor torque, and

φ is defined as in Equation (18). Under near-design conditions, ARES exhibits significant accuracy. Conversely, the predicted maps depart from the experimental measurements, as off-design operations are considered. This behavior is more emphasized at higher values of

, denoting a tendency to underestimate the rotor torque by up to

. Differently, the discrepancy is reduced at lower values with a

. The smooth monotonic trend of the curve is representative of the code stability over a wide range of operations.

As local statistics, spanwise distributions of normalized velocities and pressure coefficients are considered at design condition

(

Figure 8). From the analysis of the tangential velocity component (

Figure 8a) ARES can be seen to overpredict the flow turning, leading to negative values of

. Differently, during experiments, this component was essentially suppressed downstream of the rotor. Thus, continuity forces the axial component to decrease, thereby producing the left-shift observable in the corresponding distribution. The total pressure curves underscore a tendency of the model to underestimate losses, depicting stably higher values than the test data (

Figure 8b). However, the behaviour is not monotonic, with the greatest discrepancy occurring near midspan. Globally, the combination with the overprediction of the velocity distribution enables the model to recover a good agreement between the computed and measured static pressure fields. Anyhow, the curve is stably above experiments.

3.3. AxWJ-2

The test case represents a notional model for the validation of waterjet pump numerical models [

27,

31,

34]. Here, the geometry is selected to evaluate the code accuracy for a rotor–stator configuration, featuring a shaped duct with a variable cross-sectional area. Computations are performed using uniform inflow boundary conditions derived from the processed mass flow rate.

In this case, the characteristic map reports the head rise coefficient,

, and the hydraulic efficiency,

, as functions of the flow coefficient,

(

Figure 9). While the latter follows Equation (18), the other two are defined below:

where the angular velocity

expresses the rotational regime in rad/s.

ARES confirms significantly accurate near-design conditions (), with a discrepancy in the efficiency estimate, while exaggerating the head losses at higher mass flow rates. Despite keeping stable over a wide range of operating points, at low mass flow rates, the code diverges before completing the span of the experimental map. Notably, before the last simulated point, the results depict an increasing agreement with the reference measurements. Specifically, around the best efficiency point (), the efficiency is predicted with a error.

Thus, local Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) measurements from Chesnakas et al. [

27] are compared with computations at the station downstream of the rotor (

Figure 10). In this case, the spanwise distribution of the axial velocity component (

Figure 10a) significantly aligns with experiments, except for a velocity defect of the computed solution between the hub and

of the span. Then, the present method exhibits difficulty in predicting boundary layer dynamics near the shroud, where it tends to preserve the lower span evolution. Similar considerations hold for the tangential velocity component (

Figure 10b). In fact, for a major portion near the midspan, the numerical solution and test data are almost superimposed, while the lower and upper regions exhibit higher discrepancies. Especially for the latter, the results suggest scarce modeling of end-wall dynamics inside rotating domains.

The same statistics are analyzed downstream of the stator blades (

Figure 11). For this location, the disagreements are partially affected by the difference between the measurements station (at the nozzle exhaust) and the computations section (at the blade trailing edge), which differ due to the duct meridional shape variation. As a result, while the profile of the simulated axial velocity aligns with experiments (

Figure 11a), the corresponding values are lower because the code does not model the additional downstream expansion. Furthermore, the computed hub dynamics emphasizes boundary layer evolution, inducing exaggerate spanwise fluctuations in the lower span. Considering the tangential velocity component, the difference between the two solutions is large (

Figure 11b). While the wake dynamics impacts the evolution near the duct axis, the experiments exhibit an almost rectified flow. Differently, the numerical solution recovers a stably positive solution. Although the magnitudes are comparable between the computations and test data, the distribution profiles depict substantially different flow behaviors.

The results for this case study align with the two previous investigations featuring a rotor-only configuration. The code demonstrates good accuracy in predicting the flow downstream of the rotating blades, whereas larger discrepancies arise when comparing the stator blade flow to experimental data.