1. Introduction

Low back pain is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and is predicted to increase due to population growth and aging [1]. While its prevalence rises with age, most cases occur between the ages of 50 and 55 [2], resulting in an enormous socio-economic burden, as back pain is a major contributor to absenteeism [1,3,4]. The causes of pain are manifold, and treatment can be complicated when no specific disease or structural cause is known [5,6]. Treatment is generally based on the following two pillars [7,8,9]: conservative treatment, such as psychotherapy, medication, injections, and physical therapy and surgical treatment. In both cases, medical devices are frequently used. However, even when all treatment options have been exhausted, it is often not possible to achieve complete relief of symptoms [9]. A significant proportion of patients often experience recurrent or new problems [10]. To improve treatment for back conditions, reduce surgery and recovery times, minimize post-operative complications, and improve overall quality of life [8,11], new medical devices are constantly being developed [12,13].

Two examples of medical devices used to stabilize the spine are lumbar orthoses for conservative treatment [14,15,16,17] and spinal implants for surgical treatment [18,19]. The latter include screws and rods, interbody cages, and plates that are implanted for the direct fixation and fusion of the spine [20,21,22,23]. A lumbar orthosis, on the other hand, is an external device that encompasses all or part of the lumbar and sacroiliac regions of the trunk and is used to modify the structural and functional characteristics of the neuromuscular and skeletal systems [16,24]. To support the engineering design process [25] and predict the treatment outcomes of new devices, biomechanical studies are conducted [26]. These provide essential quantitative measures to ensure that the design process is not based solely on expert opinion rather than by biomechanical data and clinical evidence [27]. However, even the latest experimental methods used to study spinal mechanics and the loads and effects of medical devices have their limitations [28]. As a result, virtual models are increasingly being used, with varying levels of detail and solution approaches [29,30,31]. These models are intended to describe the existing knowledge of the complex physiology and pathology of the human body using mathematical models in order to derive useful predictions for treatment as a quantitative hypothesis [32].

A variety of different virtual spine models have been developed, which can be categorized into the following three types of numerical modeling [29,33]: finite element (FE), musculoskeletal multibody (MB), and combined FE–MB modeling. Each type of modeling has specific advantages and disadvantages and is used to answer different scientific, clinical, and engineering questions. To support the design process of medical devices, FE modeling is most frequently used [30,34]. It enables a detailed structural mechanics analysis of products or engineering designs in interaction with parts of the healthy or pathological osteoligamentous spine [28,35]. To obtain relevant results, realistic boundary conditions must be chosen that reproduce physiologically appropriate spinal loads [36,37,38]. However, the most common limitation of FE models is the absence of the muscles and tissues surrounding the spinal column [34,39]. The effects of muscle forces, body weight, and external loads due to physical activity must be represented by external forces and moments as simplified boundary conditions [38,40,41,42,43,44]. As it is recognized that the loading of the spine is highly complex due to the multiple surrounding redundant intrinsic and extrinsic muscles [45,46,47], the use of simplified boundary conditions can lead to over-simplification and inaccurate predictions of in vivo loading conditions [39,48,49,50,51,52]. Experimental [53] and simulation [54] studies have shown differences in implant loads between simplified and realistic loading conditions, which can be critical if underestimated in the design process. Muscles are also essential for spinal stability [55,56,57,58,59], which is affected by treatment with medical devices such as implants or orthoses [60,61].

To overcome these limitations and retain the advantages of FE modeling, the advantages of musculoskeletal MB modeling can be exploited in the context of a forward dynamic hybrid FE–MB model of the spine [29,33,62,63] with a muscle-driven approach [64,65,66]. These are still rarely used in spinal biomechanics and represent an alternative to coupled FE–MB models [49,52,67,68,69]. A hybrid FE–MB model allows for the calculation of the stresses and strains of specific structures while using rigid bodies and muscles in a single simulation step. This avoids, for example, the technically and mechanically complex coupling of two or more separate FE and MB models, which is necessary for the two-way exchange of simulation results and model synchronization [33,67]. A muscle-driven approach also allows for the simulation of movement and posture by predicting the muscle activation patterns for a dynamic musculoskeletal spine model and its interaction with the environment [66,70]. Such a hybrid FE–MB model can be used, for example, to conduct virtual technical feasibility studies and engineering designs of medical devices to clarify their interactions with biomechanical factors and generate new knowledge to improve patient care [31,71,72,73].

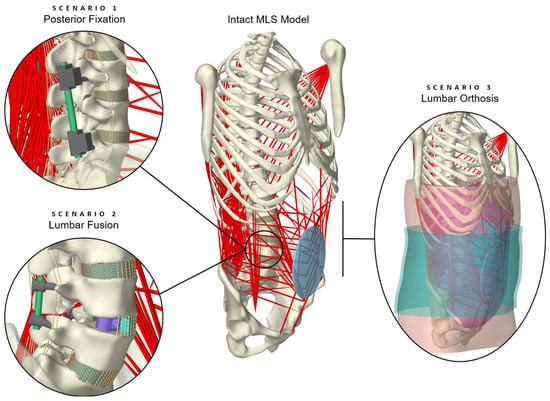

The aim of this study is, therefore, to illustrate a novel model for predicting in vivo-like loading conditions of the lumbar spine treated conservatively or surgically with medical devices. For this purpose, a previously validated intact hybrid FE–MB spine model [74] was modified in three exploratory scenarios, fitted with implants or an orthosis. The model validity was evaluated for different physical activities, including a comparison with data from the literature for the biomechanical responses of the FE and MB components, as well as the internal loads on the spinal implants. As the entire model was muscle-driven, the stabilization mechanisms of the muscle forces were also evaluated and passive minimal models without muscle influence were extracted and validated in advance.

4. Discussion

Determining the internal dynamics of the human spine under realistic loading conditions is an essential step towards a better understanding of the treatment of low back disorders. Therefore, the purpose of our present study was to develop a forward dynamic hybrid FE–MB model capable of predicting the effects of the interplay between passive and active spinal structures, as well as medical devices. The modeling process involved adapting our previously validated active MLS model [74,75] to include different treatment scenarios. The back and abdominal muscles, facet joints, and all spinal ligaments were included. Intervertebral discs, implanted devices, abdominal soft tissue, and an orthosis were modeled using 3D finite elements with linear and non-linear material properties. The comparisons with available in vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies showed a high validity of the three scenarios in the context of the simplified passive OLS and the entire active MLS model.

Even if this model offers a new way to validly study clinical scenarios under enhanced loading conditions, some general limitations must be noted. Firstly, only one model was created and modified in three scenarios. The effects of subject variability could not be addressed. In order to reduce the time currently required for the largely manual creation of such a model, automated pipelines [135] using a deep learning approach [136] may be a way to generate larger cohorts of patient-specific models in the future. Individual segment masses, which are essential for MLS models, could also be more easily predicted from image data using artificial neural networks [137]. Due to the complexity of the model and the scarcity of data from the literature, we validated the model incrementally. This was under the assumption of component validation [138], assuming that models consisting of well-validated sub-models are likely to be valid. The OLS model [75] and the intact MLS model [74] based on it were extensively validated in advance. The investigations in this study were limited to sagittal tasks, the results were evaluated when the entire model reached a static state (equilibrium), and this research was not intended to address specific clinical objectives [16]. However, as a new simulation approach was realized to predict the interdependent effects of implants and orthoses on a muscle-driven musculoskeletal lumbosacral spine model, the three variants were sufficient for a proof of concept. Future studies can include different physical activities to investigate new or patient-specific implant and orthosis designs. Therefore, the proposed model can be used as a basis for a prediction tool for the internal dynamics of the spine in the virtual product design of medical devices. In addition, manufacturers could be supported in proving their compliance with regulatory requirements, necessary under the Medical Devices Regulation (MDR, EU-V 745/2017) before placing such devices on the market in the European Union. These involve demonstrating safety and efficacy, with the potential benefit to the patient increasing with the level of risk.

A key differentiator from comparable spine models is the inherent representation of muscles in the hybrid MLS model. To determine the muscle forces that produced coordinated spinal movements, an optimization routine was utilized. Using a simplifying optimization-based routine, however, may not realistically represent physiological muscle activation patterns lacking a physiological basis, leading to errors in predicted muscle forces [29,139], and internal loads. Validations of the directly correlated spinal loads are, therefore, even more relevant. As appropriate in vivo data are difficult or almost impossible to obtain and are often difficult to justify ethically, the available in vivo studies are limited. For different postures and situations, we compared the results of our model with in vivo data on lumbar IDPs [127,128,129] and internal loads in implanted posterior fixators [36]. There was good to very good agreement, which led us to conclude that the calculated muscle force patterns were valid predictions. It should be noted, however, that in previous studies [140], similar lumbosacral model responses were found for different muscle force predictions for the major spine extensors. As it is very difficult to measure the electrical activity of autochthonous muscles in vivo, there is a lack of data to test mathematical models in this respect [47]. Furthermore, the current optimization routine could not explicitly account for co-contractions of the abdominal and oblique antagonistic muscles [29], as used, for example, when lifting heavy loads [141], which resulted in a tendency to underestimate their activities.

The muscle-driven approach used enabled the forward dynamic MLS model to be moved and held in different body postures without prescribing complete spinal kinematics. However, as partial kinematic specifications were also part of the multi-criteria optimization, an influence is inevitable [142]. For this reason, we examined and minimized the influences of the rotational contributions of the vertebral target frames on the MLS model responses in a previous study [74]. In the first two scenarios of this study, we adopted the hypothesis proposed by Panjabi [123] that a fusion causes an intervertebral motion redistribution that enables the patient to achieve the same ROM as before the surgery. Therefore, we kept the total thoracic ROM and modified the expected rotational contributions of the vertebral tracking target frames based on preliminary examinations with the OLS model. The limitations of this approach were that it is uncertain how individual intervertebral rotation contributions break down and whether patients actually have the same lumbar ROM after fusion surgery. In the in vivo study by Rohlmann et al. [36], for example, patients were asked to move as much as possible without pain. Because the ROM varied, we calculated the internal loads on the fixators for extension and flexion angles from −10° up to +30° and compared the deviations (see Figure 8a). In addition, the pelvis was fixed so that the simulated flexion of the upper body could not represent a combination of hip and lumbar spine movements [125].

Further common limitations of muscle-driven and forward dynamics simulation approaches in the context of clinical biomechanics are a high computational complexity, the required model accuracy, and a Sim2Real gap. A predicted movement or posture is the result of a dynamic interplay of all modeled structural components. This requires a high degree of model accuracy concerning all load-bearing structures (cf. Figure 3) and the motor control unit, which predicts individual muscle activation patterns [65]. As a consequence, forward dynamics simulations do not generate residual forces and moments, but may continuously diverge from experimental data (e.g., kinematic tracking), which is referred to as Sim2Real gap [31]. The computational times were significantly increased with driving muscle excitations compared to the passive OLS model. Using a desktop PC with Intel Core i7-13700K @ 3.40 GHz, 32 GB Ram, and 1 TB SSD running Windows 10 Pro 64-bit, scenarios 1, 2, and 3 took a maximum of 48, 95, and 89 minutes, respectively. Overall, the unavailability of detailed internal loads in other methods emphasizes the importance of a forward dynamics approach as the most powerful approach for investigating changes in mechanical biological spinal structures [143].

As is usual with numerical models [34], this study used an idealized situation for spinal fixation and lumbar fusion. Factors that were disregarded included, for example, pathological bone elasticity, muscle injury, incomplete resection of the cartilage endplate, spinous process fracture, and poor blood supply. All intervertebral discs were modeled as non-degenerated, which is rarely the case for treated in vivo segments [144] and is often the reason for the surgical procedure [37,122]. As a result, both ROMs [145] and IDPs [146] may have been affected. Our internal fixators were simulated without preloading. In reality, this is hardly possible due to the fixation of the screws, results in deviations in the internal loads [89], and can have a strong effect on the mechanical behavior of the bridged region [125,126]. The bone–screw connections were assumed to be ideally bonded, with no relative movement or loosening. Even if this may represent a realistic scenario after complete osseointegration [147], a stiffer construct can be assumed for the primary stability condition tested here. For the posterior fixations and the cage, the available reference data could not be exactly replicated, which may be a factor contributing to differences in the biomechanical model responses. For the screws, this does not allow for a valid assessment of their failure or stress intensifications [147,148]. Our focus was on the rods and their internal loads, which were comparable to study data. The implanted cage was of a different type, narrower, and positioned more anteriorly compared to the cages in the reference study. However, in vitro studies showed that there were no significant differences between cage types in ROM with [149] and without [22,91] PF. Segment stiffness generally increases as the cage size increases, as shown in a numerical study [150]. A further simplification of our current modeling relates to cage insertion and the evaluation of cage subsidence. No bone grafts or fragments were placed in and around the cage, as is usually done [151], which contributes to better osseointegration and fusion [152]. Consequently, it can be assumed that the primary stability was reduced, since the cage contact area was smaller and the stress distribution was less homogeneous (cf. Figure 7b).

The interaction between the trunk and an orthosis is highly complex, with a variety of biological and technical factors influencing each other [24]. The modeling in the third scenario was a feasibility study for extending a detailed muscle-driven spine model to include abdominal soft tissue. Although the full validation of such a model is impossible [61], the validity of the underlying components has been confirmed in previous studies [74,75,85]. In contrast to the first two scenarios, no passive OLS model components could be compared with in vitro studies. To the best of our knowledge, there is no comprehensive study of the exact mechanism of action of lumbar orthoses [153] that would allow for the estimated biomechanical model responses to be compared under similar conditions. Only separate biomechanical responses of model components could be quantitatively compared with independent data from the literature, as follows: the IAP resulting from external radial compression [131], the pressure on the skin [60,117,118], the stiffness and deformation of the active abdominal tissue under local compression [85], and the IDP [116]. Although moderate to good correlations were found, this is the main limitation in assessing the validity of the third scenario.

Further limitations and potentials, the influences of which we consider to be particularly relevant for scenario 3, concern the diaphragm, abdominal wall, and IAP. For the diaphragm, its material properties, geometry, and function were simplified. These include orthotropic and muscle-activation-dependent non-linear material properties [82]. Furthermore, it was not taken into account that breathing and body posture influence the morphology of the diaphragm [154] and how this, together with pelvic floor contraction, contributes to an increase in IDP [155]. The abdominal wall also has a decisive influence on the IAP, the biomechanics of which depend on the variable IAP, the passive mechanical properties of fascial and muscle tissue, and the activation of the abdominal muscles [156]. The active abdominal wall is, thus, deformed both by breathing and muscle activity [157,158], as well as by the external radial compression of an orthosis [159]. One way of taking the biomechanics of the abdominal wall into account is to directly embed detailed, active fiber and aponeurosis structures into the abdominal hexahedral mesh [160]. Another option is to use a realistic active 3D FE model where the volumetric abdominal wall is modeled with separate muscle layers and muscle contractility [161]. This active compression of the abdominal content is likely to further increase the stabilizing effect of the trunk already observed in this study. In addition to the IAP, the spine compression force is expected to be increased by the co-contraction of the trunk muscles [158]. The multipoint transversal and oblique abdominal muscles of the MLS model could be replaced and the volumetric muscles could be activated by the Tracking Controller [106]. This has the advantage that the IAP acting on the thorax can only consist of the second component, as follows: (1) a surrogate force calculated from the sum of the abdominal muscle forces acting posteriorly on the abdominal plate (cf. Appendix A) and (2) the forces of the abdominal FE soft tissue acting directly on the diaphragm.

Any time-related effects on the abdominal FE soft tissue were neglected. We only examined the immediate effects after the orthosis was applied. The interaction between the soft tissue and the spine was realized using simplified contact conditions (geometric skinning of the spine) and nodal attachments. The results showed that trunk stiffness, quantified by a decrease in predicted muscle force, was increased for the same postures compared to the intact MLS model without soft tissue. This was inevitable with the current approach and must be taken into account when interpreting the results. An additional and expected increase in trunk stiffness occurred due to the external radial compression of the abdomen. The orthosis modeled corresponded to a tall and flexible belt that was tightened more than usual. In this form, it represented a simplified version of orthoses for conservative treatment and is not comparable to weightlifting belts. The latter are narrower, usually made of leather, and, therefore, almost inextensible [162]. Orthoses for treatment purposes are usually higher posteriorly than anteriorly, closed asymmetrically, and made of different fabrics with integrated reinforcements [60,117,153]. This allows for the targeted application of forces to the pelvis, chest, and abdomen, for example to decrease the lordosis angle [163,164] and to posteriorly shift the abdominal center of mass [24]. Studies have shown that the design of the orthosis has an influence on trunk stiffness [60,165], ROM [166], and muscle activity [167]. Consequently, our results were specific to the modeled orthosis in the applied position.

Source link

Robin Remus www.mdpi.com