4.2. PRAI Fused to Another Protein Still Confers Trp Prototrophy

We first wanted to test whether PRAI is still functional when fused to another protein, such as the RWDBD used in our study. If the PRAI retains its function when fused to another protein, then expression of this recombinant protein should render the strain Trp prototrophic. To test this, strain H1511 was transformed with plasmids expressing recombinant proteins consisting of only GST and RWDBD (GST-RWDBD), and consisting of GST, RWDBD, PRAI, and the myc tag (GST-RWDBD-PRAI-myc). The backbone of these plasmids has in common the

URA3 selectable marker, allowing plasmid maintenance in medium lacking Ura. To have a Ura and Trp prototrophic strain as a reference, H1511 was also transformed with two empty vectors bearing the

URA3 (pRS316) and

TRP1 (pRS314) selectable markers, respectively. Next, saturated overnight cultures were subjected to 10-fold serial dilutions and aliquots transferred to solid medium. Plates were incubated at 30 °C and the growth monitored with a document scanner. On medium containing glucose and Trp, all strains grew equally well, as expected (

Figure 2A, left panel). On medium containing galactose and Trp, all strains were able to grow (

Figure 2A, right panel). However, on medium containing galactose but not Trp, strains lacking the

TRP1 gene were unable to grow (

Figure 2A, third panel, rows 1–2), validating that growth on this medium requires Trp prototrophy. On the same medium, strains expressing proteins fused to PRAI were able to grow, and they grew as well as the strain expressing plasmid-borne PRAI from its native promoter (

Figure 2A, third panel, rows 3–6 vs. 7 and 8). This suggests that the PRAI fused to the RWDBD is still enzymatically functional. As expected, on medium containing glucose but not Trp, strains expressing native PRAI from its native promoter were able to grow, but not strains expressing the recombinant proteins harbouring PRAI from the galactose-inducible promoter (

Figure 2A, second panel, rows 7 and 8 vs. 3–6).

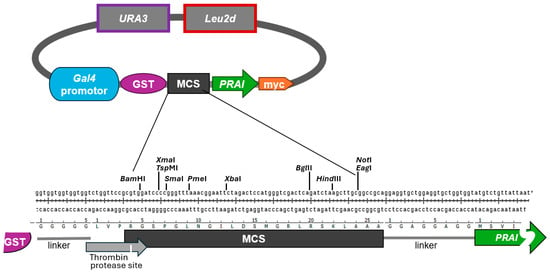

Together, our findings strongly suggest that PRA1—when C-terminally myc-tagged and N-terminally fused to another protein—is still able to confer Trp prototrophy. We are aware of the fact that PRAI function may be impacted by the type of protein it is fused to. However, we refrained from testing proteins other than the RWDBD, as one cannot forecast which proteins may impact PRAI function, if at all. To reduce the likelihood of steric interference between the protein of interest and PRAI, the vector is constructed such that the protein of interest and the PRAI are separated by the flexible eight amino acids long linker sequence GGAGGAGG (

Figure 1, bottom panel). Whenever fusing a protein of interest to PRAI, it is recommended to test whether PRAI is still functional, even if this is very likely the case. This is straightforward, as documented in our study, as well as fast and low cost.

4.3. The RWDBD Remains Functional When Fused to PRAI

With a length of 224 amino acids, PRAI is relatively large, raising the possibility that its fusion to the C-terminus of a protein of interest may affect that protein’s function. Therefore, we next tested whether RWDBD can still execute its function when C-terminally decorated with PRAI. As indicated earlier, overexpressed RWDBD hampers Gcn2 activation. Gcn2 activity can be easily scored by monitoring growth on medium containing the drug 3-amino-2,4-triazole (3AT). 3AT inhibits the histidine (His) biosynthetic enzyme encoded by

HIS3, leading to His starvation [

21]. Cells able to activate Gcn2 are able to overcome starvation and grow on medium containing 3AT, while cells unable to activate Gcn2 cannot. Hence, growth on 3AT is indicative of the level of Gcn2 activation, where the growth rate is proportional to the level of Gcn2 activity.

To test whether the RWDBD still retains its function of inhibiting Gcn2 when fused to PRAI, yeast wild-type strain H1511 was transformed with plasmids expressing from the galactose-inducible promoter GST-RWDBD and GST-RWDBD

R2259A, decorated with or without C-terminal PRAI-myc, respectively. As a control, H1511 and the isogenic

gcn1∆ strain (H2556) were transformed with a plasmid expressing GST only. A semiquantitative growth assay was conducted as above. On plates containing glucose, strains grew equally well. On plates containing galactose, strains expressing GST-RWDBD and GST-RWDBD

R2259, decorated with or without C-terminal PRAI-myc, also grew as well as those expressing GST alone, suggesting that overexpression of the recombinant proteins did not affect cell growth in general (

Figure 2B, left two panels). On medium containing galactose and 3AT, the

gcn1Δ strain was barely able to grow, as expected, since the absence of Gcn1 does not allow Gcn2 activation (

Figure 2B, row 9). Amino acid Arg-2259 in the RWDBD is critical for the interaction with Gcn2, rendering overexpressed RWDBD

R2259A unable to disrupt Gcn1-Gcn2 interaction and unable to hamper Gcn2 activation [

12]. Accordingly, as expected, strains expressing GST-RWDBD

R2259A or GST-RWDBD

R2259A-PRA1-myc were still able to grow on medium containing 3AT (

Figure 2B, right two panels, row 6–8 vs. 1 and 2). In contrast, and as expected, strains expressing GST-RWDBD showed reduced growth compared to strains expressing GST (

Figure 2B, right two panels, rows 4 and 5 vs. 1 and 2). The same growth defect was observed for the strain expressing GST-RWDBD-PRAI-myc (

Figure 2B, right two panels, row 3 vs. 4 and 5). This strongly suggests that the RWDBD retained its function even when fused C-terminally with PRAI-myc. This also suggests that the PRAI-myc did not affect the proper folding of the protein, i.e., it retained its native solubility.

From the above findings, we can conclude that the RWDBD and PRAI both retained their function when fused in-frame. This would suggest that decorating the protein of interest with a C-terminal PRAI does not impact the function of either protein. Certainly, this needs to be validated for each protein of interest investigated. In addition to a flexible linker separating the protein of interest from the PRAI, the protein of interest is also separated from the N-terminal GST tag by a flexible linker, again with the intention to reduce the likelihood of steric hinderance that may interfere with the function of the protein of interest.

4.4. The Epitope Tags of the Protein Constructs Are Detectable

The Trp prototrophy conferred by PRAI fused C-terminally to the protein of interest would indicate that the protein of interest is expressed in full length. Western blotting could be conducted to verify the correct size of the hybrid protein by probing for the N- or C-terminal epitope tags. Particularly important are Western blots where variations in expression levels must be considered when assessing the functions of different protein variants. In our plasmid system, the recombinant proteins harbour an N-terminal GST tag and a C-terminal myc tag. Very strong antibodies against GST and myc are commercially available, and both tags also allow easy protein purification or co-precipitation studies. In fact, anti-myc antibody-linked resins are commercially available, and so are glutathione resins (GST binds to glutathione).

To detect the tags via immunoblotting, transformants were grown to exponential phase in liquid medium containing galactose as a carbon source. Cell extracts were generated and subjected to denaturing SDS polyacrylamide electrophoresis and Western blotting using antibodies against GST and myc, and the housekeeping gene Pgk1 as a loading control. When probing for GST, one distinct band could be detected in each lane, with those of GST alone and GST-RWDBD-PRAI-myc at the expected size of 26 and 95 kDa, respectively. For GST-RWDBD, the detected size was slightly higher than expected (69 kDa vs. 64 kDa) (

Figure 3A). As reported previously, observed discrepancies between calculated and observed kDa values of a protein could be due to amino acid composition, post-translational modifications, protein conformation, and SDS binding, as well as variations in the accuracy of pre-stained protein markers and differences in gel composition or running conditions, which can affect protein mobility [

22,

23,

24].

When probing for myc, expected signals were only observed in the cell extracts containing recombinant proteins harbouring a myc tag (

Figure 3B). Together, this suggests that both tags are readily detectable via Western blotting.

While in Western blotting antibodies detect their epitope tag in denatured proteins, in immunoprecipitation or purification procedures, the tags need to be accessible within natively folded proteins. The N-terminal GST tag is commonly used for co-precipitation or purification approaches [

25,

26], and so is the myc tag [

25,

26]. To reduce the possibility of steric hindrance in our plasmid system, the tags are separated from the fusion protein by linkers, with the SGGGGG linker between the GST tag and the fusion protein, and the GGG linker between PRAI and the myc tag. Nevertheless, one cannot exclude the possibility that steric hindrance obstructs the accessibility of the tag in the context of a folded protein, hence it is recommended to experimentally test with each protein of interest whether the tags are accessible to antibodies or resins (e.g., glutathione-linked resins). At least for the GST-RWDBD hybrid protein, it has been shown previously that the GST tag can be used for co-precipitation studies [

12]. Since the accessibility of tags needs to be tested for any protein of interest, we refrained from conducting co-precipitation studies and from testing other hybrid proteins in our study.

4.5. Enrichment of Yeast Cells Expressing Protein Variants with Desired Phenotypes

If, for example, the scenario was to identify protein variants with improved properties from a yeast library generated via random mutagenesis, the first step would be to remove cells that express truncated proteins. We have demonstrated above that our vector system allows the removal of yeast cells expressing truncated proteins due to their inability to grow in the absence of Trp.

The next desired step would be to enrich the library for those cells that express protein variants with improved properties. This can be conducted by competitive growth, as long as the improved protein property elicits a change in phenotype that provides a growth advantage. Such competitive growth conditions would need to be optimised first. This optimisation process is outlined next using as an example our proof-of-principle study.

In our study, the desired protein function is the loss of Gcn2 binding and concomitant gain of Gcn2 function, which manifests itself phenotypically by the strain’s regained ability to grow in the presence of 3AT. Two control strains were needed, the original control strain that expresses the original protein of interest, and the positive control strain that expresses a protein with the desired improved property. In our study, these were RWDBD and RWDBDR2259A, respectively. RWDBD can inhibit Gcn2, impairing growth on 3AT, while RWDBDR2259A cannot. If a positive control protein is not available, a strain that displays an equivalent improved fitness can be used instead. In our scenario, this could have been a wild-type strain harbouring the vector alone and thus containing a fully active Gcn2, since we are looking for mutations that render RWDBD unable to bind Gcn2 and incapable of inhibiting Gcn2.

RWDBD was expressed from a plasmid harbouring only the

URA3 selectable marker (pAG01, equivalent vector is pAG41 for the original control strain), while RWDBD

R2259A was expressed from a vector harbouring both selectable markers

URA3 and

Leu2d (pSG50, equivalent vector is pAG40 for the positive control strain) (

Figure 4A,B). These plasmids were introduced into the wild-type yeast strain H1511.

First, it was necessary to identify growth conditions under which the positive control strain harbouring RWDBDR2259A grew at a faster rate than the original control strain harbouring RWDBD, i.e., had a higher fitness. The point of growth difference was the ability of a cell to activate Gcn2 under starvation conditions, which is hampered by RWDBD but not RWDBDR2259A. Therefore, we determined the optimal 3AT concentration at which there was a clear difference in growth rate between these two control strains. To do this, saturated overnight cultures of the strains were individually inoculated into medium containing galactose and increasing amounts of 3AT as before, the strains grown at 30 °C and 180 rpm overnight, the exponentially growing cultures re-inoculated into fresh medium containing the same amount of 3AT as before, and the optical density measured at 2 h intervals. As a control, we also included in our growth assays the wild-type strain and isogenic gcn1Δ strain expressing GST alone.

As expected, in the absence of 3AT, all strains grew at a similar rate (

Figure 4C). However, the

gcn1Δ strain did not grow as well as the wild-type strain expressing GST alone in the presence of 0.25 mM 3AT (

Figure 4C). The

gcn1Δ strain still showed some growth, likely because the amount of 3AT used was insufficient to fully inhibit His biosynthesis. The strain expressing GST-RWDBD

R2259A grew at least as well as the wild-type strain expressing GST alone, in agreement with the idea that RWDBD

R2259A is unable to impair Gcn2 activation, allowing the cell to overcome starvation and grow in the presence of 3AT. In agreement with previous findings [

12], the strain overexpressing RWDBD showed impaired growth in the presence of 3AT, as found for the

gcn1Δ strain, due to RWDBD impairing Gcn2 activation. The growth discrepancy between strains expressing RWDBD and RWDBD

R2259A became slightly more pronounced with increasing 3AT concentrations. For the competition study, we chose the lowest 3AT concentration that still elicited the maximum difference in growth, which was 0.5 mM.

The next step would be to perform a pilot competitive growth assay to determine the timeframe over which the culture becomes enriched with cells displaying the desired phenotype (the positive control strain), i.e., expressing the protein with the desired improved property. Galactose medium containing 0.5 mM 3AT was inoculated with cells to a final OD600 of 0.05. The inoculum consisted of a 1:9 ratio, with 1 part positive control strain (cells expressing RWDBDR2259A) and 9 parts original control strains (cells harbouring RWDBD). For the control growth assay, the same experimental setup was used, but the medium did not contain any 3AT. After every 22–24 h of growth, an aliquot was taken and the culture re-inoculated at an OD600 of 0.05 into fresh galactose medium containing 0.5 mM 3AT (or not containing 3AT in case of the control growth assay). The aliquots were 10-fold serially diluted and spread on solid media lacking Ura or lacking both Ura and Leu. Plates were incubated at 30 °C until colonies emerged, and the number of colonies determined. All strains were expected to grow on plates lacking Ura, while on plates lacking Ura and Leu, only strains that harboured the plasmid bearing RWDBDR2259A (the positive control strain) were expected to grow since its backbone carries the Ura3 and Leu2d selectable markers. This allowed us to determine in the competitive growth culture the ratio of cells expressing GST-RWDBDR2259A (positive control strain) to those expressing GST-RWDBD (original control strain), and to follow over time any changes from the initial 1:9 ratio.

According to the colony counting results, as expected, the strain expressing RWDBD dominated at 90% at the start (

Figure 5A). After 72 h, its abundance reduced to 4%; accordingly, the strain expressing RWDBD

R2259A became the prominent strain (

Figure 5A). It appears that the point of equal ratio between the two strains was between 24 and 48 h. Since the strain expressing RWDBD remained the predominant strain on medium lacking 3AT over the equivalent time period (89% abundance), and since after 120 h this was still the case (83% abundance), this supports the idea that the selection pressure imposed by 3AT drove the change in the ratio between cells expressing RWDBD vs. RWDBD

R2259A. Taken together, these results suggest that 72 h of competitive growth were sufficient to dramatically enrich the strain with the desired phenotype.

Next, we wanted to obtain additional evidence of the effectiveness of the competitive growth procedure in enriching the strain with the desired phenotype. The idea behind the next assay is that the more abundant a strain is in the competitive growth culture, the more abundant its plasmid should be; hence, PCR applied directly on an aliquot of the competitive growth culture should yield a larger proportion of amplicons originating from the more abundant plasmid. To test this, we used PCR primers that amplified a portion of the RWDBD that encompasses the amino acid Arg-2259, the point of difference between the RWDBD and the RWDBD

R2259A proteins. Another difference was that the R2259A substitution removed the nearby

AseI restriction site. This meant that the PCR amplicons originating from the RWDBD versus the RWDBD

R2259A templates could be distinguished by a subsequent

AseI restriction digest, where only the amplicons from the RWDBD template were cut but not the amplicons from the RWDBD

R2259A template; hence, after resolving the digested amplicons via agarose gel electrophoresis, they could easily be identified and quantified (

Figure 5B, lanes 1 and 2 vs. 3 and 4). The same was true for a mixed sample where the RWDBD

R2259A and RWDBD templates were in a 1:9 ratio (

Figure 5B, lanes 5 vs. 6). At the start of the competitive growth assay, restriction digest of the PCR amplicons revealed that the 364 and 149 bp bands (PCR product containing the restriction site) were more abundant than the 513 bp band (PCR product lacking the restriction site) (

Figure 5B, lanes 7 and 8), suggesting that the strains expressing RWDBD were more abundant, as expected. Upon quantification of the band intensities, the RWDBD abundance was 90% and 88.5% for the competitive growth and control culture, respectively, which aligned well with the expected 90% (

Figure 5C). After 48 and 72 h of growth, the 513 bp PCR product originating from the RWDBD

R2259A template increased in abundance compared to the bands originating from the RWDBD template (

Figure 5B, lanes 10 vs. 12 vs. 13). Quantitation of the bands revealed that the strains expressing RWDBD

R2259A increased to 64% and then to almost 100% abundance. Growth beyond 72 h resulted in the positive control strain maintaining a level of 100%. Together, this indicated that 72 h of competitive growth was sufficient to enrich for the positive control strain expressing RWDBDR

2259A.

In the control culture lacking 3AT in the medium, the 364 and 149 bp bands (PCR product originating from RWDBD) remained more abundant than the 513 bp band (PCR product originating from RWDBD

R2259A) over time (

Figure 5B, lanes 7, 9, 11, 14, 15, 17). The starting 10:90% ratio between the positive and original control strains only changed to a ratio of about 25:75% and 17:83% after 72 and 129 h, respectively, as opposed to 0:100% after just 72 h in the competitive growth culture grown in the presence of 3AT (

Figure 5C). This means that the positive control strain was barely enriched under conditions lacking 3AT, supporting the idea that the enrichment of the positive control strain was not by chance but due to the selection pressure imposed by 3AT. This is in agreement with the colony counting results above (

Figure 5A).

In summary, the colony counting approach and the liquid culture PCR-based assay gave similar results. Both assays indicated that the 10:90% ratio between the positive and original control strains shifted to a 50:50% ratio between 24 and 48 h, and that at 72 h, the abundance of the positive control strain was almost 100%. This suggests that a competitive growth of only a few days (here 3 days) was sufficient to enrich for strains with higher fitness, expressing the desired protein of interest with improved properties. Beyond 72 h, the colony-counting-based assay seemed to indicate that the ratio shifted from 4:96% ± 2% back to about 20:80% (28:72% ± 10.21% at 96 h and 15:85% ± 1.6% at 120 h), suggesting that competitive growth after reaching the point of maximal positive control strain proportion (here at 72 h) may not be advantageous. Nevertheless, the desired strain still remained the majority. On the other hand, the PCR-based assay seems to indicate that the 0:100% ratio remained unchanged beyond the 72 h of competition. However, it is possible that ethidium bromide-based staining may make it hard to detect low-abundant DNA in the gel. Nevertheless, the PCR-based assay still allows for the determination of whether the positive control strain became enriched in the culture. Another important advantage of the PCR-based assay is that—unlike a colony-based assay—it provides results in less than 24 h. This is critical for determining whether to continue a competitive growth culture, as it needs to be re-inoculated every 24 h. In contrast, a colony-based assay takes up to 2 days, making it too slow for timely analysis during an ongoing competitive growth assay. However, to use a PCR-based assay, a DNA sequence that is unique to the original strain or to the strain with improved property is essential, e.g., by way of presence or absence of a restriction site.

Following the competition assay, one could then identify the gene mutations responsible for providing increased strain fitness by performing targeted sequencing using next-generation sequencing techniques. The technique used can be amplicon sequencing, third-generation, or massive parallel sequencing, depending on the length of the DNA to be sequenced [

28,

29,

30,

31]. If there are several protein variants that enhance fitness, next-generation sequencing will not only reveal the sequence of the gene of interest variants eliciting enhanced fitness, but also reveal the relative abundance of the respective plasmids in the culture. Strains containing the plasmid-encoded protein conferring the highest fitness would be the most abundant.