This story is part of a Grist package examining how President Trump’s first 100 days in office have reshaped climate and environmental policy in the U.S.

Across seven decades and a dozen presidencies, America’s scientific prowess was arguably unmatched. At universities and federal agencies alike, researchers in the United States revolutionized weather forecasting, cured deadly diseases, and began monitoring greenhouse gas emissions. As far back as 1990, Congress directed this scientific might toward understanding climate change, after finding that human-induced global warming posed a threat to “human health, and global economic and social well-being.”

Donald Trump and his new administration evidently disagree. In the first 100 days of his second stint in the White House, the president has released a slew of orders that destabilize this apparatus. Earlier this month, the administration effectively scrapped the government’s comprehensive National Climate Assessment — a quadrennial report that provides scientifically-backed guidance for how towns, cities, and regions can prepare for a hotter climate — when it canceled a contract for the firm that facilitates the research. Recently leaked memos, reviewed by Grist, show the White House hopes to slash scientific research at NASA and eliminate all research at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, which is responsible for a host of climate, weather, and conservation science. And two weeks ago, the administration froze over $2 billion of research funding to Harvard — the latest in a series of punishments targeting the nation’s top schools that the president claims have become overrun by “woke” ideology.

Experts fear this siege against science could jeopardize the United States’ status as a global leader in climate research. Since Trump took office in January, the federal government has frozen billions of dollars in climate funding and grants for universities. At the same time, Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency has decimated the federal workforce, firing thousands of scientists, in a purported attempt to cut a trillion dollars in “waste and fraud” from the federal budget. This month, Musk’s team began canceling hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of scientific grants distributed by the National Science Foundation. And last week, Secretary of State Marco Rubio shuttered the Office of Global Change, which oversees international climate negotiations.

“One of the things that has made America great and will keep America great is our scientific excellence and world leadership in climate science,” said Max Holmes, who leads the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. “Gutting those things will send our country in a different direction.” While other countries may fill the void, he said, the loss of American research and expertise will affect the entire world.

Eamon Queeney / The Washington Post via Getty Images

One way of measuring a country’s scientific heft is by looking at the number of papers its researchers publish. For the last quarter century, American scientists have churned out some 400,000 studies each year — an unrivaled pace that has remained consistent throughout presidential administrations until China’s scientists surpassed it in 2016. This is largely thanks to the federal government, which has been the country’s largest overall funder of science and research since World War II.

Until now, no former president — including Trump — has tried to dismantle this legacy. For example, the fourth edition of the National Climate Assessment, a recurring report mandated by Congress under the auspices of the U.S. Global Change Research Program in 1990, was nearly complete the first time Trump took office in 2016. Although his administration limited the report’s publicity when it was released, they did not alter the contents of the report, according to federal scientists who worked on it.

But this go-round is different: On April 9, the Trump administration ended the contract with the consulting firm responsible for running the U.S. Global Change Research Program — a likely fatal blow for the sixth National Climate Assessment, which was due to be published in the next few years.

“For hundreds and even thousands of years, we humans have been making decisions based on conditions of the past,” said Katharine Hayhoe, a leading author of the last four assessments and a climate scientist at Texas Tech University. “It’s like driving down the road looking in the rearview mirror. But now, thanks entirely to human actions, we are facing a curve in the road greater than we humans have ever confronted.”

Other consequences of ending the Global Change Research Program are more immediate. The program’s interagency working groups are the primary way that federal agencies collaborate on climate problems, sharing data and expertise on greenhouse gas monitoring and sea level rise. Federal scientists told Grist that the program was essential for efficient communication between agencies and that without it, continuing these collaborations may not be possible.

The program also facilitates the United States’ participation in the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, through which scientists from nearly 200 countries work together to create a global report with the latest climate science.

“The U.S. has long had a profound presence at these reports — we have excellent research capacity,” said Kevin Gurney, an atmospheric scientist at Northern Arizona University and a leading author on several IPCC reports. “Politics aside, having the best available knowledge on climate change problems is crucial.”

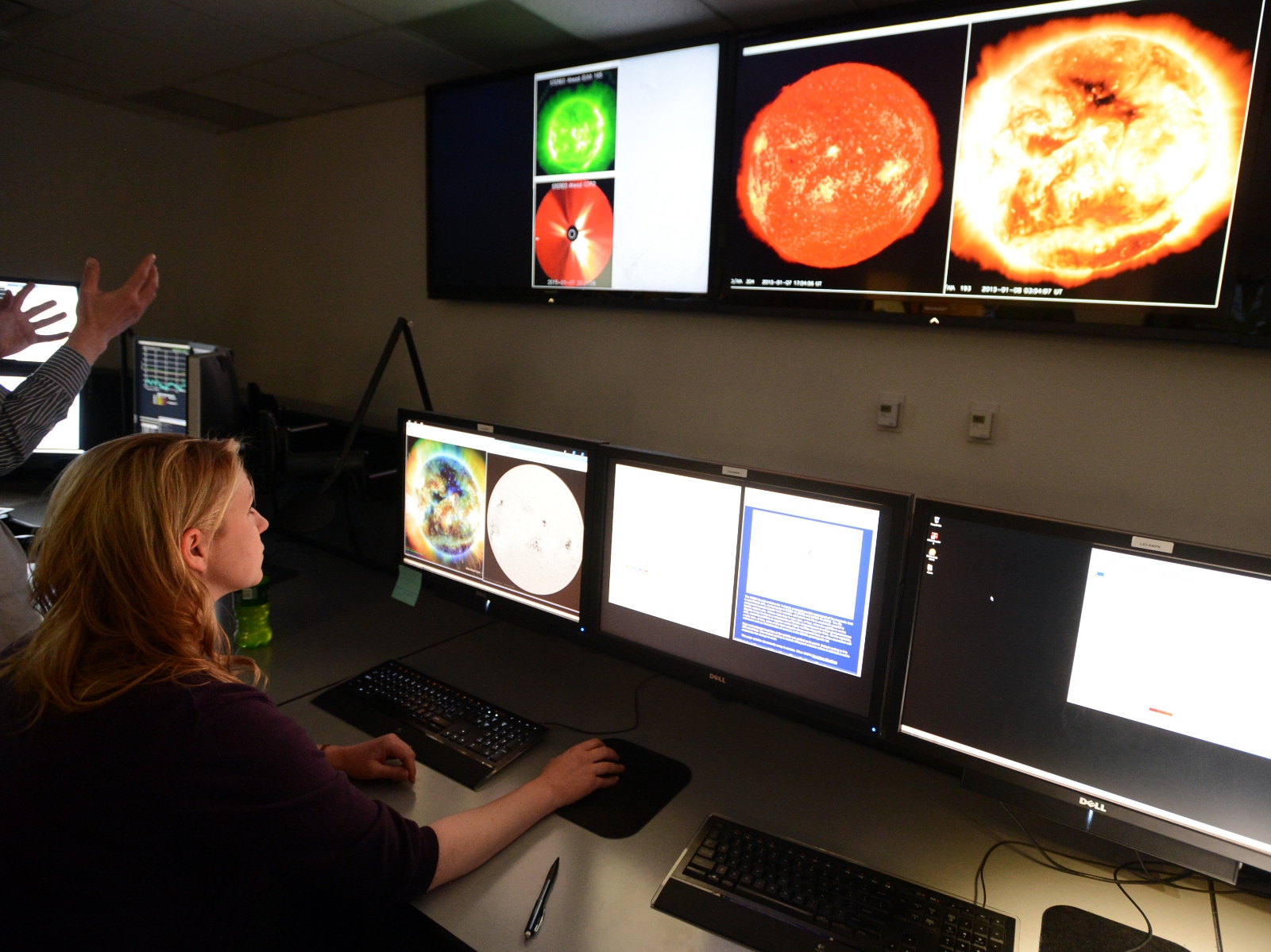

The Washington Post via Getty Images

Gurney noted that because America’s scientific workforce is so large and holds a wealth of research, climate models, and data, a diminished U.S. presence deprives other countries of crucial climate information. Pulling back could also dampen American input and influence over the contents of the IPCC report — which is used to inform international climate mitigation policies, such as a recently announced international shipping tax that aims to reduce emissions.

“There’s loss in both directions,” Gurney said. “I worry that it’s going to take us years to regain the momentum and capacity that it seems we’re just frivolously letting go of right now.”

In March, Gurney — who is not a federal employee — was one of a few U.S. scientists who attended an IPCC meeting in Japan after the Trump administration barred federal delegates from attending an IPCC planning meeting the previous month. In light of crumbling government support, a group of 10 American research institutions recently came together to form the U.S. Academic Alliance, which aims to preserve U.S. participation in the report. Hosted by the American Geophysical Union, the alliance is stepping up in place of the federal government to handle nominations for U.S. scientists to contribute to the next IPCC assessment.

The scientific research that fuels these assessments is under threat, too. In a recently leaked budget memo, known as a “passback,” the Trump administration laid out a plan to gut NOAA’s coffers by 27 percent, eliminating the agency’s entire research arm and closing all weather and climate labs. This includes the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawai‘i, which has provided the longest running measure of atmospheric carbon dioxide, as well as ocean-monitoring stations that support seasonal hurricane forecasts and key projects for gauging sea level rise and cataloging impacts of warming in the Arctic.

Beyond losing crucial data on the changing climate, culling science at NOAA will “hurt every aspect of society,” said Rick Spinrad, who led NOAA under Joe Biden’s administration. The data produced by the agency’s research division supports a wide range of government services, such as disaster management and agricultural forecasting. And because the agency’s research capacity, equipment, and expert workforce took decades to build up, the losses can’t be easily recovered.

“The American public needs to understand that you can’t just turn a science switch off and then turn it back on again,” Spinrad said. “This is not like tariffs.” He pointed out that while NOAA’s budget is small — just 0.01 percent of the federal budget, by some estimates — it plays an outsize role in American lives. It also financially benefits taxpayers far more than it costs them: A recent study by the American Meteorological Society found that every dollar invested into the National Weather Service returns $73 in value for the public.

Wekeli / iStock via Getty Images

The passback budget document also includes guidance to reshuffle the small parts of NOAA’s research division that may be spared into other parts of the agency. But because NOAA’s various offices are so interconnected, Spinrad said breaking it up and reorganizing it will disrupt the entire agency’s ability to function.

“The idea that all of this is predicated on government efficiency is really contradictory,” he said. “The consequences will be risks to lives, property, and economic development. There’s no question of that.”

Over the past couple weeks, other agencies that conduct climate science have received passback budget memos too. The budget proposal for NASA reveals the administration’s plans to halve the space agency’s science funding — docking over $3 billion from its 2026 budget. The cuts would likely mean that NOAA and NASA will no longer be able to launch the next generation of Earth-observing satellites, which provide crucial data for climate and weather forecasting.

MediaNews Group / Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s passback memo sent to the Department of Health and Human Services reportedly proposes slashing $40 billion from its budget. Many offices and programs inside the department — which houses the National Institutes of Health and the Center for Disease Control — would be shuffled, consolidated, or eliminated entirely. According to internal documents reviewed by The New York Times and ProPublica, National Institutes of Health programs and grants for studying the health impacts of climate change will no longer be funded, and the agency’s new policy is “not to prioritize” research related to climate change.

The Trump administration also plans to amputate the Environmental Protection Agency’s scientific arm, a move that means laying off thousands of scientists. On April 15, amid reports that the EPA plans to gut its greenhouse gas monitoring program, the U.S. missed the deadline to report its emissions to the United Nations for the first time in three decades.

“Essentially everything that is related to how we understand climate is on the table for being cut,” said a scientist who has worked at NASA and who requested anonymity. “We’ll just be flying blind while the planet is undergoing some of the most significant impacts and changes that have been experienced.”

The funding cuts could also imperil climate research outside the government. Many federal agencies, such as NOAA, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health, play a large role in providing universities grants to pay for research and fund graduate students. But in recent weeks, the Trump administration has frozen billions of these dollars as part of its investigation into antisemitism at over 60 universities, catching climate research in the broad net.

In 2018, the last year that the Government Accountability Office took stock of federal climate funding, the government was spending over $13 billion on climate change research, with many agencies providing grants to universities or collaborating directly with them. The National Institutes of Health and the Department of Energy have both revoked large chunks of funding to universities, sparking lawsuits. In mid-April, the National Science Foundation — which provided $800 million toward climate research in 2018 — froze all grant applications as Elon Musk’s team began combing through its books. Crowdsourced information from scientists shows that on April 18, DOGE had canceled hundreds of millions of dollars in grant funding. The agency has already been operating cautiously since Trump took office, funding 50 percent fewer grants than this time last year.

And in early April the Commerce Department announced $4 million of funding from NOAA would be pulled back from Princeton’s Cooperative Institute for Modeling the Earth System, which helps create improved weather forecasts and model water availability. According to reporting in The Washington Post, the Trump administration says the initiatives are “no longer aligned” with the agency’s objectives and that the research contributes to climate anxiety by promoting “exaggerated and implausible climate threats.”

“Climate science is important in tackling a complicated problem, but a lot of this is not about the research,” said David Ackerly, dean of the Rausser College of Natural Resources at the University of California, Berkeley. “The research funding is being used as a political pawn in a battle about something else.”

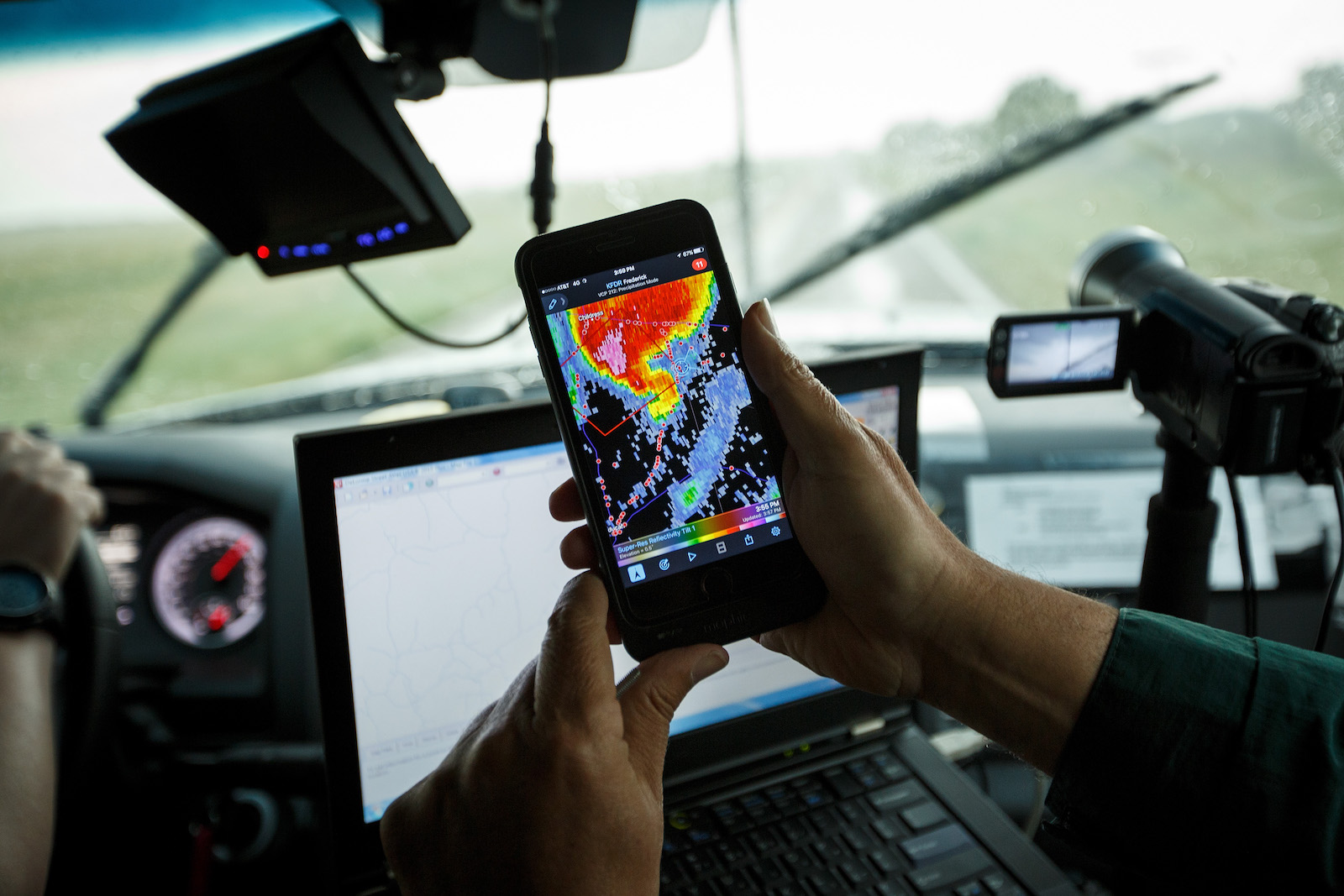

A scientist looks at radar on a smartphone as part of a group tracking a 2017 supercell thunderstormin Olustee, Oklahoma. Their research includes funding from the National Science Foundation and other government grants.

Ackerly said it’s too soon to know how the broadly applied cuts might reshape climate science done at universities, but expressed concerns that a generation of students could lose confidence in pursuing careers in higher education. International students — who earn roughly half of all graduate degrees in science and technology fields — may forgo coming to study in the U.S. at all. Some schools have already tightened their belts by freezing or restricting their graduate admissions. Because graduate students provide the workforce necessary to conduct scientific studies, run laboratories, help teach classes, and write papers, the slimming of student populations means less climate research can be produced in the United States.

“Our ability to educate the next generation of people to do this work is starting to be cut off,” said Gurney, the IPCC author. “It may take a while and we may not notice it at first, but we will. This is damage that could last for a long time.”

Holmes, of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, said that the escalating cuts signal to the international community that the U.S. is stepping back from leadership in climate research. With so much uncertainty, he said, scientists may begin to seek opportunities in other countries.

“Other countries will take the lead if we cede it, because we need leadership in climate solutions and science”

It appears the brain drain has already begun. According to a recent analysis from Nature, data from the scientific journal’s job board indicates that American scientists have submitted 32 percent more applications for international jobs during the beginning of this year compared to last year. In March alone, U.S.-based job seekers viewed international job listings 68 percent more than last year. At the same time, applications to U.S. institutions from European researchers fell by 41 percent.

Some European institutions are actively trying to attract American scientific talent, too. In March, France’s Aix-Marseille University said it was “ready to welcome American scientists” and created the Safe Place for Science program to sponsor those working in climate, health, and environmental fields. Germany’s top research institution, the Max Planck Society, announced in early April a new transatlantic program to create collaborative research centers with American institutions. After job applications from the U.S. researchers doubled over last year, the institution’s president said he is planning to tour U.S. cities to speak to Germany’s “new talent pool”. According to Nature, recruiters in China have also been targeting career ads toward fired American scientists.

“Other countries will take the lead if we cede it, because we need leadership in climate solutions and science,” Holmes said. “The sooner we can right the ship, the sooner we can get heading in the right direction again.”

Rachel Cleetus, a senior policy director with the Union of Concerned Scientists, said that nothing should be considered final until Congress approves the federal budget later this year. “Congress needs to push back on these disastrous cuts, because this scientific enterprise has been built up by investments over decades from U.S. taxpayers,” she said. “This is the crown jewel of science and expertise for our nation — even the world.”

Even if the lost funding is restored, Ackerly said the Trump administration’s attacks represent an unprecedented breakdown in the government’s longstanding support of science and research. It is this relationship, he said, that fosters a uniquely robust network of both private and public universities, and has made higher education and science in the United States stand out among other countries for decades. But now, said Ackerly, a new normal is being established.

“This will always be part of a history we live with,” he said. “You can never fully go back to where things were before.”

Source link

Sachi Kitajima Mulkey grist.org