1. Introduction

Africa has the highest urban growth rate worldwide [

1]. According to the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), the urbanization rate has increased from 35% in 2000 to 43.5% in 2020 (Urbanization and Development Section|United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (uneca.org)). This increase in urban population is often reflected in substantial land consumption through the growth of urban footprints. Of relevance, it is small and medium-sized cities (henceforth referred to as “secondary cities”) that have experienced the strongest demographic growth in the past four decades in Africa [

2,

3].

The marked urban growth of secondary African cities is expected to continue and even intensify in the years ahead. According to the United Cities and Local Governments [

3,

4], by 2030, two out of three new urban dwellers in Africa will settle in a small- or medium-sized city. The scale and speed of these urban transformations are unprecedented, and present enormous challenges. However, despite the critical role secondary cities seem to play in African urbanization, they are rarely the specific focus of urban studies. Indeed, several recent works have raised the concern that secondary cities in Africa still receive much less attention than capital cities from academics, politicians, experts, and donors [

5,

6,

7]. They have been neglected by public authorities and research, despite being characterized by highly informal systems for which there are few data [

8] and rapid, unplanned urbanization. They suffer from a lack of attention and support from research, raising many questions about their future. Scientific research in Africa tends to focus on metropolises, which are supposed to be the main centers of economic growth and innovation.

One of the main concerns related to the growth of secondary cities in Africa is to better understand the management of land, including the rate of land consumption and resulting urban forms [

9]. Land is a genuine support for all societal development processes [

9], and rapid urbanization and the sprawling growth of secondary towns are causing rapid changes in land use [

10,

11]. The outward expansion of cities fostering scattered urban forms is a palpable sign of unplanned and poorly managed urbanization [

12]. The most critical impacts of this situation could be the disappearance of the original plant cover and the suppression of the agricultural activities on which a significant part of the urban population in Africa depends [

2].

In this context, how can we ensure that these rapidly growing secondary towns are constructive partners in sustainable development? Given the impacts of urbanization on the quality of living environments and ecosystem services [

13,

14,

15,

16], it is imperative to better understand the different urbanization processes happening in Africa, which are still at an early stage (as compared to other regions in the world) and, possibly, identify concrete examples of sustainable urbanization.

There is already a robust body of research using remote sensing to detect, map and quantify the evolution of urban footprints, both across the globe and in Africa and at various spatiotemporal resolutions [

1,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Notably, a recent study assessed the urban land use expansion across Africa [

22], based on the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 11.3.1. Such studies are essential for achieving the SDGs, notably those linked to SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), which includes targets related to sustainable and efficient land use.

While there is a large amount of “top-down” studies quantifying urbanization in secondary African cities [

23], recently emphasized there is a critical lack of “bottom-up” urban studies aiming to understand urbanization from the residents’ perspective. In fact, we argue there is a need for mixed studies directly connecting quantitative, earth observation data, with qualitative, primary data obtained from residents and decision-makers. This more comprehensive approach is key to better understanding context-specific drivers of urban growth and the diversity of urban forms across different locations.

West Africa is particularly affected by planning challenges related to the rapid growth of secondary cities, making this region a fertile ground for urban studies. There, urbanization “is going faster than anything else: faster than economic growth and productive investment, faster than urban planning and management” [

24]. As in the rest of the continent, secondary cities in this region have absorbed most of this urban growth, accounting for 56% of the urban population [

4]. For instance, in Togo and Ghana, between 1960 and 2020, the number of urban agglomerations with less than 30,000 inhabitants rose from 3 to 47 in Togo, and from 28 to 155 in Ghana; those between 30,000 and 300,000 went from 1 to 17 in Togo, and from 6 to 64 in Ghana.

The impact of urbanization on landscape patterns and the extent of urban sprawl in these growing secondary cities remains unclear [

25]. However, despite the critical role secondary cities seem to play in African urbanization, they are rarely the specific focus of urban studies. They receive less attention from academics, politicians, experts and donors working on the urban fabric [

6]. It is very important to know the extent and spatial configuration of urban growth in order to improve decision making [

25].

Most existing studies in West Africa focused on large cities [

12,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], while the few studies that focused on secondary cities [

6,

23,

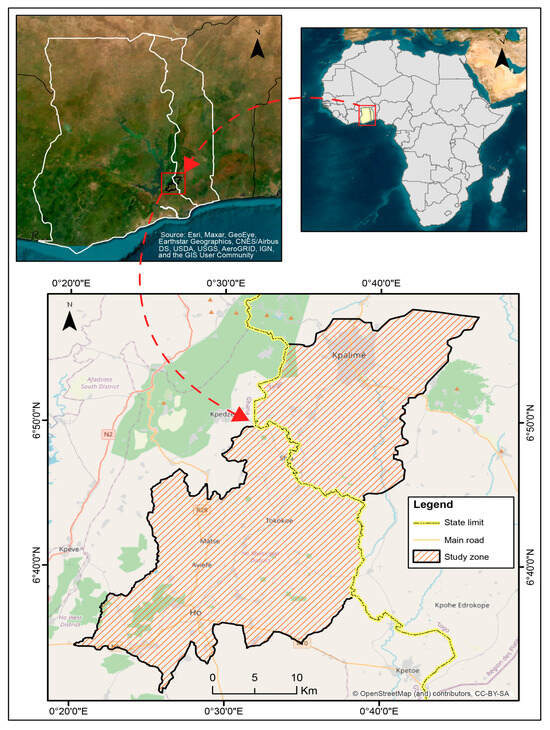

31] were either qualitative or quantitative, but never mixed. Moreover, to our knowledge there are no comparative studies assessing whether different urban governance frameworks can explain differences in urban forms. This study addressed this research gap by conducting a mixed methods analysis of the urban expansion of two secondary cities in West African countries under different governance frameworks: Ho (Ghana) and Kpalimé (Togo).

This study aimed to answer the following questions: what are the historical dynamics in terms of urban and demographic growth in those two secondary cities? What factors explain these dynamics, from the perspective of local residents and decision-makers? To answer these questions, we employed mixed methods, using qualitative information from stakeholder interviews to discuss the determinants and temporal variations of urban growth in the two cities, quantified by satellite imagery.

5. Conclusions

This comparative, mixed methods study, the first of its kind between two secondary cities under different urban governance contexts, strengthens the literature on urbanization dynamics in West Africa. This study provided empirical evidence on the drivers of rapid and diffuse urbanization. Most importantly, it showed that the effective management of urban growth in secondary African cities is possible, as seen in Ho. The analysis of population growth and land consumption rates in Ho and Kpalimé showed that these two secondary cities are currently marked by the phenomenon of urban sprawl, but have undergone very distinct urbanization processes. Whereas Kpalimé showed a constant trend towards sprawl over the period of 1985–2020, Ho experienced compact urbanization between 1985 and 2010, and only more recently has its urban footprint grown faster than its resident population.

According to our interviews with various stakeholders in Ho and Kpalimé, the determining factors behind the urban sprawl recently observed in these two cities were as follows: the absence of housing policies aimed at low-income populations, the absence of or non-compliance with master plans and urban policies, the preponderance of single-family housing, land speculation, and the location of infrastructures and road networks.