At Climate Week NYC, across a wide range of topics from finance to law, energy to food, infrastructure to conservation, one message rang clear: We need more collaboration, particularly across diverse stakeholders.

This message is nothing new. If you are engaged in environmental or societal issues, you would most likely agree that no single actor or sector has the capacity, incentive or mandate to truly address the systemic problems we currently face. The calls for collaboration, therefore, were mixed with an odd sense of déjà vu. One audience member was heard groaning, “If one more panelist says we need more collaboration, I’m going to lose my $#!t!”—reflecting a deeper struggle within the climate community to understand how, exactly, we can make such collaborations happen.

One Climate Week event addressed this challenge by focusing on something many of us can relate to: our daily coffee. The event, Sustainable Prosperity for Coffee Farmers: An SDG-Based Approach, was led by Lara Fornabaio, lead researcher at the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, and Jeffrey Sachs, president of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. It served as a launchpad for a new handbook, Prosperity for Coffee Farmers Through SDG-Based Coffee Plans, that showcases a methodology for collaborative investment planning, to align finances and the diverse incentives, across stakeholders, in coffee-producing regions.

Why coffee? Because coffee is a highly traded commodity subject to climate risks like drought, as well as supply chain risks, and it offers a good use case in facilitating collaboration across the public and private sectors by aligning their interests, capacities and mandates.

Sachs, an economist at heart, opened the event with a lighthearted comment on how any disruption to the world’s coffee supply would “create a disruption to the world’s productivity.” But his words underscore a serious problem: coffee prices are on the rise due to a supply squeeze, not only because of recent tariffs, but also due to climate change in coffee-exporting countries like Brazil, which is preparing to host this year’s Conference of Parties (COP). In Brazil, coffee-producing regions like Minas Gerais are currently facing an intense drought, recording about 70% of the average rainfall, depressing crop yields.

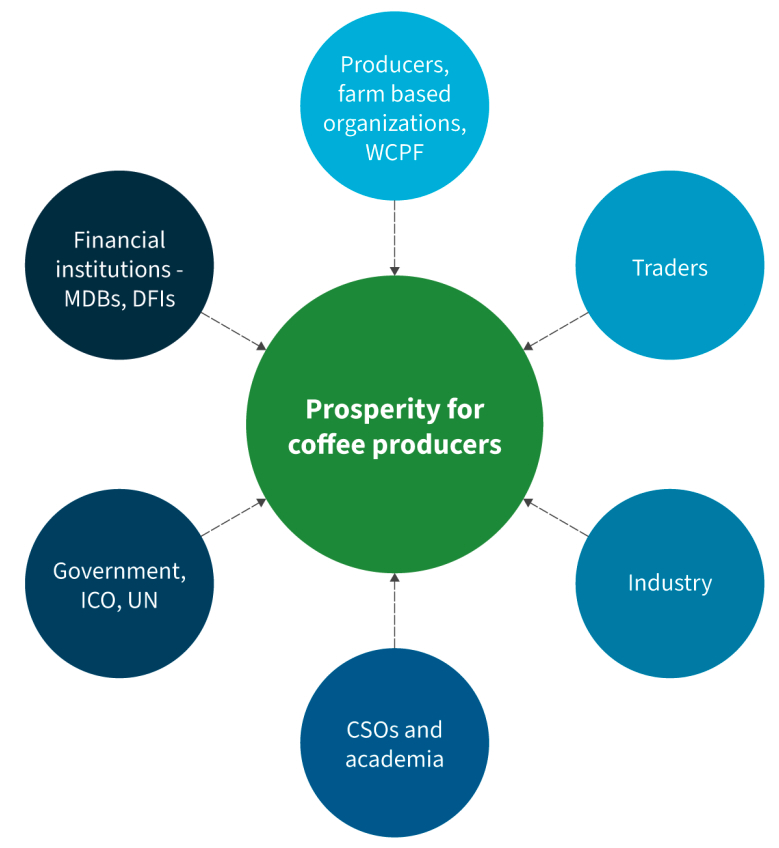

Developed by Fornabaio and Sachs, this methodology for collaborative investment planning may not just bode well for the coffee sector, but for other key commodities, resources and technologies. Speaking with State of the Planet, Fornabaio highlighted the crux of sustainable investment challenges. “Often it’s not about a lack of financing mechanisms, but coordination and planning, across various tools like public subsidies, short-term loans and concessional finance, which each respond to specific use cases within the broader system.” She provided an example: “The private sector will not build schools, or clinics, or provide pensions to coffee growers—that requires public investment in critical social services and infrastructure. Meanwhile, governments won’t mobilize capital to make supply chains more resilient—that’s the responsibility of the private sector to ensure they can continue producing coffee.” It’s about identifying these areas for investment, figuring out which ones are high priority for the farmers, and directing finance from the sources—both companies and public institutions—that are best incentivized to administer these funds.

Fornabaio and Sachs wrote the handbook to address this lack of coordination and planning among the many coffee supply-chain stakeholders. The handbook was developed through field simulations in Colombia, Costa Rica and Brazil, and acknowledges that the coffee sector needs a holistic approach to planning around coffee production at the national and sub-national levels. Climate change is throwing the Earth’s ecosystems off-kilter, impacting the continued production of commodities like coffee—a key concern for coffee companies across the world. But beyond the immediate threat of climate change, coffee farmers have historically been price-takers—in other words, they sell at prices the market dictates—and face high rates of poverty and food insecurity, with very limited social protection.

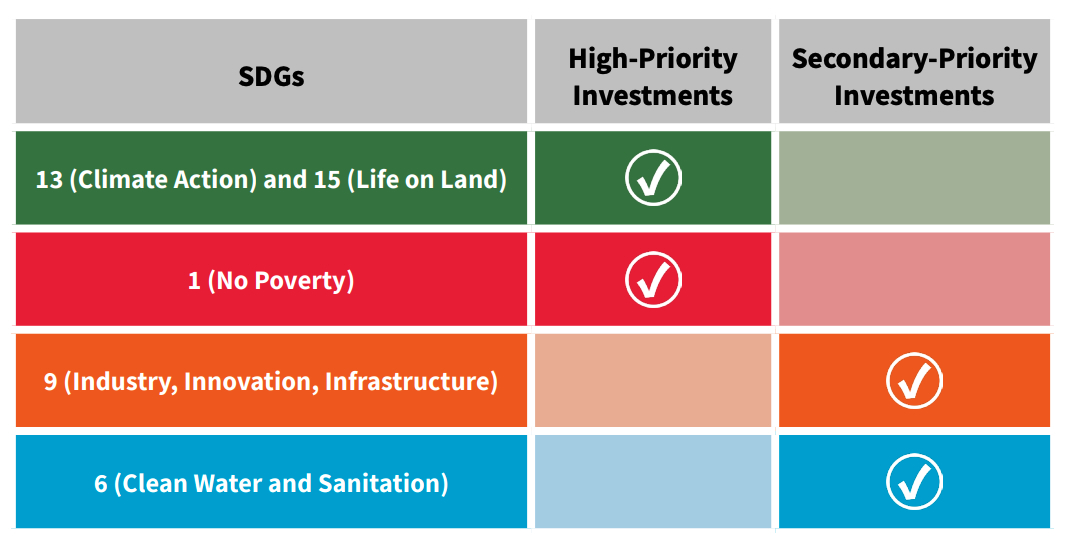

The handbook provides a three-step participatory methodology to assess financing needs and gaps across the various dimensions of this challenge, using the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a framework to develop investment roadmaps that coordinate public and private investments across priority areas ranging from social protection for farmers to technologies for climate adaptation. The SDGs work as a framework for this, said Fornabaio, because they help take into account the socio-economic challenges farmers face, in tandem with the environmental challenges.

Key to addressing these challenges is identifying the actual, not perceived, challenges. “We cannot finance what we don’t clearly define,” said Fornabaio, who underscores the need for farming communities to participate in the process of identifying areas for investment that are most important for them. Through data analysis and stakeholder interviews, quantitative and qualitative research, we can better understand the region in terms of progress toward the SDGs and other issues that farmers say matter to them, such as the availability of credit.

The handbook goes beyond current industry practices like certifications and due diligence in value chains, to help coffee-producing regions develop a coordinated investment approach to achieve the SDGs. Once investment priorities are identified, the methodology provides a costing equation to quantify the SDG financing gaps. These gaps—i.e., how much it costs to achieve the SDGs—are then addressed through an investment roadmap. The objective of each investment is then paired with the appropriate financing tools and the actors best positioned to do something about it.

Due to the issues outlined above, COP30 is already being called the “implementation COP.” On the agenda are several key issues to address regarding mitigation and adaptation, with strong calls for national climate plans, and frameworks for coordination between countries, companies and communities. But national plans and coordination are a necessary starting point, whether addressing biodiversity, food systems resilience or emissions reduction.

Set against the backdrop of the Amazon, COP30 will unfold in one of the most biodiverse places on Earth. There, the world will be asked to confront how investments in nature and food systems not only help us adapt to climate risks, but also advance nature-positive outcomes. There is a clear appetite to address the world’s deepest collective action problems, but without a clear understanding of what these problems are and why they persist, there is little we can do.

Systemic challenges require system-wide responses from governments, companies and international organizations alike. These responses necessarily need plans of action that play to the strengths, incentives and mandates of those who are best positioned to tackle each piece of the puzzle. Implementation hinges on appropriately sequencing and coordinating cross-sector efforts—no amount of technical assistance or finance will solve climate challenges without clarity on local priorities and the mandates of those positioned to act. And this is what Fornabaio hopes the handbook might help accomplish—she will be at COP this year, handbook in hand, focusing on food systems investment planning.

“It’s time to address the real bottleneck for implementation: collaboration and planning,” Fornabaio said. “COP could be an opportunity for participants to apply the principles of the methodology outlined in the handbook, and create practical plans in the face of climate change.”

Source link

Guest news.climate.columbia.edu