2.2. Adaptive Varifocal Liquid Lens Based on DEA

Compared with traditional varifocal lenses, the adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by DEA is superior in terms of compactness, speed, efficiency, and flexibility. The typical structure of the adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by DEA has a liquid medium fully encapsulated by deformable film or enclosed by a chamber and an elastic membrane, as shown in

Figure 2a.DEA is presented wrapped around the lens surface or integrated into the membrane. The fluid is pressurized so that the initial curvature of the lens membrane bulges out when it is not activated [

56]. Inspired by the adaptive lens structure of the human eye, Carpi et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by DEA [

51,

57]. As shown in

Figure 2a, the proposed lens consisted of a liquid medium enclosed by the annular optically transparent DE, and the remaining part of the membranes is coated with a compliant-electrode material that can apply voltage to the DE. The DEA of the adaptive liquid lens was arranged along the optical path. When a voltage was applied to the electrodes, the surface area of the DE increased because of the decrease in radial tension. It resulted in a decrease in the diameter of the adaptive varifocal liquid lens, which led to an increase in the thickness of the liquid lens. It caused a decrease in the radius of curvature and focal length of the adaptive varifocal liquid lens. The proposed adaptive liquid lens had a focus length range from 16.72 mm to 22.73 mm when the applied voltage increased from 0 to 3.5 kV. The adaptive varifocal liquid lens used an acrylic-polymer-based film as DE material, whose dielectric strength and optical properties of polyacrylate surpass those of PDMS [

58]. However, using acrylic elastomer membranes as DE material and carbon grease electrodes applied by hand makes the DEA slow, exhibits large viscoelastic drift, and has short lifetimes [

59]. Using silicones or polyurethanes as DE material, which is less viscous, can achieve faster focal length tuning [

60,

61,

62]. By using silicones as DE material, Shea et al. proposed an adaptive liquid lens driven by DEA, as shown in

Figure 2b [

59]. This adaptive liquid lens had the fastest response time so far, whose response time was less than 175 μs. The proposed liquid lens consisted of two pre-stretched films with a liquid (2–8 μL in volume) sealed between them, ring-shaped flexible electrodes coated on the upper and lower surfaces of the DE, which were fixed by two rigid PCB boards. When the driving voltage was applied to the compliant electrodes, the DE squeezed the fluid causing its radius of curvature to decrease. Thus, the focal length of the liquid lens decreased. The initial focal length of the adaptive varifocal liquid lens depended on the volume of the liquid encapsulated between the two membranes. The settling time of the lens was shorter than 175 µs, and a 20% change in focal length was obtained. This proposed liquid lens driven by DEA had extreme strain, fast response speed, and good stability, which means that it can be used for high-frequency varifocal applications and fields where compliance and speed are needed.

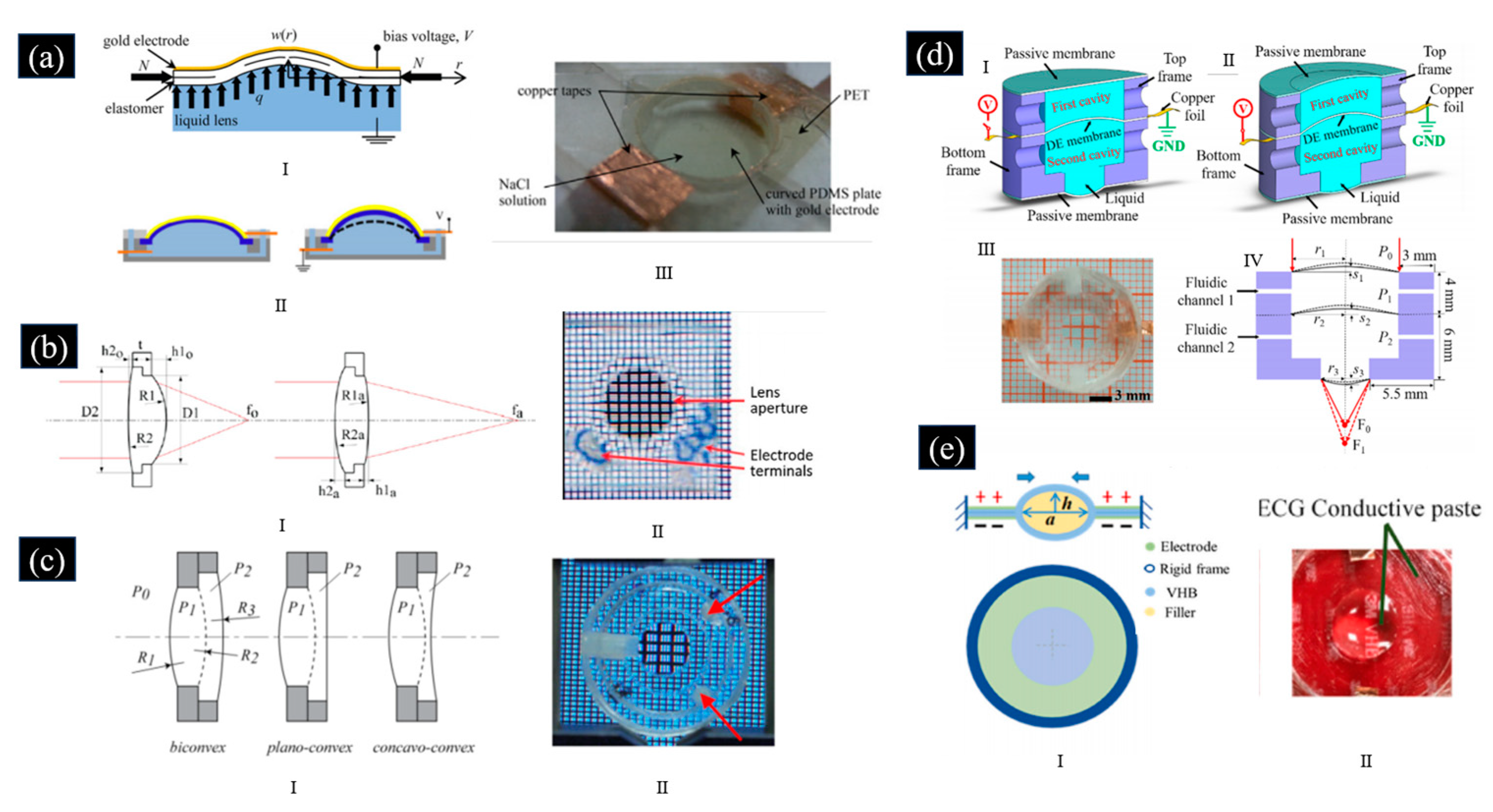

Figure 2.

(

a) I. The principle of the adaptive varifocal liquid lens is based on the DEA proposed in [

57]. II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

57]. (Reproduced with permission from [

57]). (

b) I. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

59]. II. Photograph of fabricated adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

59]. (Reproduced with permission from [

59]).

Figure 2.

(

a) I. The principle of the adaptive varifocal liquid lens is based on the DEA proposed in [

57]. II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

57]. (Reproduced with permission from [

57]). (

b) I. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

59]. II. Photograph of fabricated adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

59]. (Reproduced with permission from [

59]).

The compliant electrode deposited out of the central region of the DEA above is opaque, which makes the dimensions large and the available optical aperture small [

51,

57,

59]. To address this issue, some DEAs using transparent compliant electrodes were developed to make the structure of adaptive liquid lenses more compact [

52,

63,

64,

65]. Liang et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by DEA with transparent ionic electrodes, as shown in

Figure 3a [

63]. The DEA consisted of a curved PDMS thin film sandwiched between a gold electrode and the NaCl solution. Because movable ions in NaCl solution can conduct electricity, it can act as an ion electrode for DEA. The electrostatic force induced radial compression when a bias voltage was applied and caused the lateral deflection of the PDMS. It led to the radius of curvature of the lens being altered and then changing the focal length. The focal length of the adaptive liquid lenses had a focusing range from 16.1 mm to 13.1 mm as the applied voltage increased from 0 to 900 V. Due to the use of NaCl solution, the breakdown voltage of the DEA was only 1400 V. So, the focus length tuning range of this liquid lens was narrow. Moreover, the deposition of the gold layer reduced the transmittance of the adaptive liquid lens. For the wavelength between 390 and 770 nm, the transmittance of the fabricated PDMS plate was higher than 90%, but it decreased to 50–70% after the gold layer was deposited. Shian et al. produced and evaluated highly compliant transparent, compliant electrodes, including single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and silver nanowires (AgNWs) [

66]. The results showed that SWCNT electrodes had better optical transparency and a higher figure of merit for actuation than AgNW electrodes. Shian et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens based on DEA using SWCNT electrodes [

52,

64]. The adaptive varifocal liquid lens required only a minimal number of components, i.e., a frame, a passive membrane, a DEA, and a clear liquid, as shown in

Figure 3b [

64]. The transparent DE membrane was coated with SWCNT electrodes on both sides, and the passive membrane was arranged along the optical path [

66]. When a voltage was applied to the DE, DE deformed then the tension in the membrane decreased, causing a concomitant decrease in liquid pressure resulting in a decrease in fluid pressure. Then, the radius of curvature of DE and the passive film were changed, which changed the focal length. The liquid lens had a focal length change range greater than 100% and a response time of less than 1 s. Building on the foundation above, Shian et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens based on DEA coated with SWCNT electrodes, consisting of a stiff frame cavity separated into two same liquid-filled cavities by a transparent DE membrane [

52]. The other side of the DE membrane was a passive elastomer membrane in each cavity. As shown in

Figure 3c, the liquid pressure in the left cavity (P1) was greater than the environmental pressure (P0), making the adjacent membranes bulge outward, while the liquid pressure in the right cavity (P2) was less than P1. Thus, the curvature of the passive membrane in the first cavity was convex, while the curvature of the passive membrane in the second cavity can be convex (P2 < P0), flat (P2 = P0), or concave (P2 > P0), depending on the amount of fluid in the second cavity. When a voltage was applied to the DE, DE deformed then the tension in the membrane decreased, causing a decrease in P1 and an increase in P2. As the diameters of the passive membrane (D1 and D2) were not equal, the difference in the curvature between the two membranes made the focal length of the adaptive liquid lens change. When the driving voltage varied from 0 to 4500 V, the optical power of the lens changed from 66 m

−1 to 17 m

−1, the change rate in the focal length was 300%, and the response time was 35 ms.

However, the SWCNT deposition process is complicated, and the strain actuation of the SWCNT is low for a DEA because its high stiffness impedes dielectric deformation [

65]. We proposed an adaptive varifocal lens using DE sandwiched by transparent conductive liquid, whose fabrication process is free of the deposition of the opaque compliant electrodes [

65]. As shown in

Figure 3d, the proposed lens consisted of two PMMA frames, two passive membranes, and a transparent conductive liquid separated by a DE membrane. The volumes of the liquid in the two cavities were constant, and the hydraulic pressures gave the liquid lens an initial focal length. When a driving voltage was applied to the copper foils, the shape of the DE membrane changed, which in turn changed the shapes of the two passive membranes, and then the focal length of the liquid lens was changed [

67]. The liquid was made by mixing glycerol and sodium chloride at a 10:0.1 weight ratio, which not only served as the refractive material of the tunable lens but also worked as the compliant electrode of the DE. The lens proposed has a compact structure and high transmittance, and the fabrication process was simpler and free of the deposition of opaque compliant electrodes. The transparent gels generally have a low Young’s modulus and high stretchability, which can response fast and strain largely [

68,

69]. It is also desirable to replace traditional electrodes with transparent conductive gels for the adaptive liquid lens based on DEA. Zhang et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal lens using EGC (electrocardiogram) conductive gel as the electrode of the DEA, as shown in

Figure 3e [

70]. Compared with traditional carbon grease electrodes, EGC gels have a greater electrostriction rate and a lower driving voltage. In addition, the ionic gels also possess high transparency and stability. The lens is fabricated by using the negative pressure method which makes the lens structure stable during operation [

71]. The proposed lens has potential applications in the biomedical imaging field.

Figure 3.

(

a) I. Side view of adaptive liquid lens based on DEA in [

63]. II. Side view of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

63] without applying voltage (left) and lens when a bias voltage was applied (right). III. Photograph of fabricated adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

63]. (Reproduced with permission from [

63]). (

b) I. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

64] at the rest state (left) and during actuation (right). II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

64]. (Reproduced with permission from [

64]). (

c) I. Three possible geometrical configurations of the adaptive liquid lens are proposed in [

52] at rest. The ambient pressure and pressure in cavities 1 and 2 were indicated by P0, P1, and P2, respectively. II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

52]. (Reproduced [

52] with permission from SPIE Publishing). (

d) Architecture of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

65] at the rest state (I) and the activation state (II). III. Photograph of the fabricated adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

65]. IV. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

65]. (Reproduced with permission from [

65] © Optical Society of America). (

e) I. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

70]. II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

70]. (Copyright (2023), Reprinted from [

70] with permission from Elsevier).

Figure 3.

(

a) I. Side view of adaptive liquid lens based on DEA in [

63]. II. Side view of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

63] without applying voltage (left) and lens when a bias voltage was applied (right). III. Photograph of fabricated adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

63]. (Reproduced with permission from [

63]). (

b) I. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

64] at the rest state (left) and during actuation (right). II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

64]. (Reproduced with permission from [

64]). (

c) I. Three possible geometrical configurations of the adaptive liquid lens are proposed in [

52] at rest. The ambient pressure and pressure in cavities 1 and 2 were indicated by P0, P1, and P2, respectively. II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

52]. (Reproduced [

52] with permission from SPIE Publishing). (

d) Architecture of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

65] at the rest state (I) and the activation state (II). III. Photograph of the fabricated adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

65]. IV. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

65]. (Reproduced with permission from [

65] © Optical Society of America). (

e) I. Schematic of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

70]. II. Photograph of the adaptive liquid lens proposed in [

70]. (Copyright (2023), Reprinted from [

70] with permission from Elsevier).

The DEA used in the lenses mentioned above works as an in-plane actuator. Here, several adaptive varifocal liquid lenses using conical DEA were proposed, whose DEA worked as an out-plane actuator [

72,

73]. Our group proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by a conical DE, as shown in

Figure 4a, which consisted of two conical DE, compliant electrodes, a liquid droplet, three annular PMMA frames, several screws, screw nuts, as shown in

Figure 4a [

72]. When a voltage was applied to the electrode, the DEA made the middle PMMA frame move upwards, increasing the surface curvature of the droplet which caused the focal length to decrease. The proposed adaptive liquid lens is 9.4 mm in diameter and 12.5 mm in height. Cai et al. proposed a DEA tunable lens controlled by an electrooculographic (EOG) signal, whose two pre-stretched DE films and lenses form a biconical structure, as shown in

Figure 4b [

73]. Two DE films and encapsulated salty water form the lens at the central part of the structure. The salty water and the annular carbon grease worked as the electrodes for the DEA. When a voltage was applied to the electrode, the annular electrode area expanded so that the radius of curvature of both sides of the lens decreased and the focal length increased. Each of the two DE films had four separate active areas. The movement of the lens can be controlled by comparing the EOG signals from the left–right channel and the up–down channel. The proposed lens has potential applications in visual prostheses and the medical field.

As a liquid droplet can present a lens character because of its biconvex shape and its smooth surface, liquid droplet lenses based on DEA, which can be fabricated with a more compact structure, have been proposed [

74,

75,

76,

77]. Ren et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens for millimeter and micron diameter apertures by filling a droplet into the hole of the DE film, as shown in

Figure 5a [

74]. Initially, the focal length of the liquid lens was the longest when no voltage was applied. When a drive voltage was applied to the DE, the aperture of each hole shrunk, causing the diameter of the droplet to decrease. It led to an increase in the curvature of the liquid, so the focal length of the liquid lens became shorter. The liquid lens can be easily prepared, and the proposed liquid lens has a fast response. Zhao et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid droplet lens, as shown in

Figure 5b [

75]. When a voltage was applied to the DE, the DE exhibited an in-plane expansion, which compressed the center areas that were not covered by the carbon black coating. That changes the contact of the droplet and changes the focal length. Our group proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by DEA with a transparent conductive droplet, which acted as the material of the lens and the compliant electrode of the lens, as shown in

Figure 5c [

76]. When a voltage was applied to the droplet, the area of the DE expanded, which decreased the diameter of the droplet and increased the focal length of the lens. The droplet lenses proposed above have a compact structure and a simple fabrication process. To reduce the gravitation effect, the droplet lens should be controlled in micro size and placed in the horizontal position. Due to the small dimension, the droplet lens has potential applications in various compact imaging systems.

Most adaptive varifocal liquid lenses based on DEA mentioned above have DE films used as both the lens membrane and the actuator [

52,

57,

59,

64]. The main advantages of this architecture are the compact size and the simple fabrication process [

78]. Nevertheless, it challenges membrane puncture, the stability of the lens, and the optical property of DEA caused by sharing of the same elastomeric membrane [

56]. As the lens with DEA arranged along the optical path suffers from the challenges of membrane puncture and the stability of the lens and the optical property of DEA caused by sharing of the same elastomeric film, Lau et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens with a DEA diaphragm pump, as shown in

Figure 6b. The DEA diaphragm separated two hydraulic chambers, which were filled with oil [

56]. Oil impregnation improved the high dielectric strength and life of DEs. When there was a voltage applied to DE, the DE membrane expanded outward and the fluid pressure of the lens changed, altering the curvature, which led to a change in focal length. The volume of the hydraulic chamber was larger than the volume of the lens chamber. So small deformations in the electroactive film can cause larger deformations in the lens film, resulting in a larger change of the focal length range. The liquid lens had a diameter of 8 mm and could focus on 15 cm and 50 cm targets at a drive voltage of 1.8 kV. Zhao et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by a concentric ring DE encapsulated in a self-adapting film, as shown in

Figure 6b [

79,

80]. Since no stretching of the DE membrane was needed, the mechanical instability of the lens was greatly reduced. When a voltage was applied to the ring DE, it led to the transmission of liquid in the lens portion and the driving portion. The focal length variation at 1 kV driving voltage ranged from 25.4 mm to 105.2 mm (when the initial bow height was 273 μm), and the maximum focal length variation exceeded 300%. By separating the lens and actuator, the reliability and performance of the lenses were enhanced. Separating the lens and actuator allows unrestricted choice of lens film materials with better optical properties or stretchability. This also allowed the DE to reduce the thickness independently from the lens film to reduce the driving voltage [

56]. However, this architecture occupies a larger volume.

Using more than one kind of fluid can also develop adaptive varifocal liquid lenses, which change the focal length by controlling the meniscus shape between the fluids. The adaptive liquid lenses using two immiscible liquids driven by DE were proposed [

81,

82]. Rasti et al. proposed a DE stack actuator-based adaptive varifocal liquid lens, which can reduce the driving voltage [

81,

83,

84]. This liquid lens consisted of two insoluble liquids and a membrane actuator, as shown in

Figure 7a. In this case, distilled water and silicon oil were employed, which were separated with a membrane actuator. The center of the membrane had a hole with a diameter of 4 mm. The meniscus acted as a lens whose focal length can be changed by changing the rectangular shape. When a voltage was applied to the DE, DE deformed and resulted in a change in meniscus shape and a change in focal length. The focal length of each lens had a focusing range from 6 to 35 mm as the applied voltage increased from 50 V to 750 V. Ren et al. proposed an adaptive varifocal liquid lens using two immiscible liquids, as shown in

Figure 7b [

82]. The meniscus acted as a lens and formed in the opening area due to the interfacial tension, and the aperture of the lens was confined using an iris diaphragm (ID). The two liquids had a spherical interface, and their boundary was defined by a variable aperture. By applying a voltage to the bubble driver, the aperture of the aperture can be changed, and the surface profile of the two liquids is altered; thus, the focal length is changed. The two liquids were separated by the blades of the variable aperture, except where they met at the center opening. Due to the interfacial tension of the liquids, a curved surface is formed at the opening area. When a voltage was applied to the electrodes, the DE film expanded and pushed the connector to move upwards. Then, the lever rotated and changed the aperture. When the dimension of the opening area was changed, the contact angle and the focal length were changed because of the balance of the interfacial tension. At an applied voltage of 8 kV, the height of the DE film rose by 6.9 mm, approximately 25% of the initial height, the control rod rotated by 11°, and the aperture increased or decreased by approximately 2 mm. The lens using two immiscible liquids driven by DE has the advantages of large aperture change and good mechanical stability.

It is difficult to bind two components together without affecting structural homogeneity and avoiding the formation of defects, so it remains a challenge to create DEA-based lenses with a high dielectric constant together with both mechanical and optical properties. Using electrohydrodynamic (EHD) 3D printing technology, Zhou et al. proposed a polymer-based adaptive varifocal liquid lens driven by DEA, as shown in

Figure 8 [

85]. EHD printing is an efficient, simple, and low-cost fabrication technique using an electric field to create the fluid flows necessary for delivering inks containing high-content fillers to a substrate [

86,

87]. The printed lens exhibited a 29% change in focal length from 33.6 mm to 26.1 mm under a dynamic driving voltage signal control. Furthermore, it displayed excellent stability when the focal length was tuned from far to near (30.1 mm to 25.3 mm) for 200 cycles.

2.3. Adaptive Varifocal Soft Solid Lens Based on DEA

Due to the liquid-based adaptive varifocal lens still having challenges in environment stability and preventing liquid leakage, an all-soft solid adaptive varifocal lens driven by DEA has become a good choice [

56,

88,

89]. The DEA-based soft solid adaptive varifocal lens has the advantages of fast response, large aperture, and small thickness, making it more suitable than a liquid lens for applications that are particularly sensitive to mechanical vibrations, temperature changes, and distortions introduced by gravity [

90].

When the DEA of the soft solid lens is involved in optical path refraction, the structure of adaptive varifocal lenses can be more compact. A soft varifocal solid lens driven by DEA was proposed by Kim et al. and it was obtained by bonding a silicon lens and DEA tightly, as shown in

Figure 9a [

91,

92]. The DEA was made of stacked nitrile butadiene rubber film, and liquid carbon was dispensed for creating electrodes. By the application of voltage to the actuator that extends its area, the silicon lens became thicker and had a smaller curvature, and then the focal length was changed. The lens can be zoomed 1.04 times with a high driving voltage. Son et al. proposed a DEA-based varifocal solid lens, as shown in

Figure 9b [

78,

93]. Different from the lens above, the DE film, which acts as a lens, was made of silicone rubber with high transmittance. The thin DE membrane coated with transparent, compliant electrodes was confined by rigid boundaries; the compressive force caused the material to expand when a large enough voltage was applied. Then, the membrane became either convex or concave whose curvature can be changed by applying the voltage, so a variable focal length was achieved. Though this lens did not have a high varifocal ratio, the lens’s structure is simple and compact since the lens itself functions as the actuator.

Inspired by reptile and bird accommodation, Carpi et al. proposed a soft varifocal solid lens driven by a peripheral annular DE, which can achieve large tuning ranges, as shown in

Figure 10a [

90]. The thin DE coated with transparent, compliant electrodes on both sides was radially pre-stretched on a circular rigid frame. When a voltage was applied, the DE squeezed towards the center part while the outward expansion was blocked by the rigid frame, causing a decrease in the diameter of the electrodeless part that hosts the lens. Thus, the focal length of the lens can be changed, and the tunable lens was capable of focal length variations up to 55%. Using an acrylic-based DE with high optical transparency simplified the fabrication process and reduced drive voltage but also made the lens have a low response speed and hysteretic behavior.

Compared with acrylic and polyurethane elastomers used as the material of the DEA field, silicone has lower viscoelastic losses, higher response speed, and higher stability in general [

55,

59,

94]. By using silicone as the material of both a solid lens and DE, Carpi et al. proposed a varifocal solid lens driven by DEA [

55]. The proposed lens was an electrically reconfigurable, fully elastomeric, tunable lens with motor-less electrical controllability of astigmatism in the visible range [

55]. As shown in

Figure 10b, four independently controlled electrodes (S1-S4) are printed on one side of the actuator, and zoom and dispersion can be achieved by applying voltages to each of the four electrodes, depending on the situation. Using silicone materials with high dielectric coefficient and low Young’s modulus, Yoon et al. proposed a varifocal solid lens driven by disk type DEA, which has the features of simple structure, compactness, and good performance, as shown in

Figure 10c [

95]. The lens consisted of a soft lens and a DEA which can enable purely in-plane radial actuation of lens diameter and consequent curvature change. Performance test results showed the lens had 93% focus length change capability and a response time of 7 ms, which was 1.4 times the focusing capability (65%) and 9.4 times the response time (67 ms) of previous lenses [

96]. The results indicated that the material of the DEA has a strong influence on the performance of the lens. Using silicones can have a lower viscoelastic loss, more stable performance, and higher response speeds [

90].

Figure 10.

(

a) I. Schematic of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

90] at relaxed state (the left) and accommodated state (the right) II. Top view of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

90]. III. Lateral view of a prototype adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

90] at electrical rest(top) and under maximum actuation (bottom). (© IOP Publishing. Reproduced with permission from [

90]. All rights reserved). (

b) I. Schematic of the varifocal solid lens proposed in [

55]. II. Schematic lateral sectional view of the lens proposed in [

55] at electrical rest (top) and under actuation (bottom). III. Photograph of the varifocal solid lens proposed in [

55]. (Reproduced with permission from [

55]). (

c) Structure and operation principle of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

95] with no voltage (I) and with a voltage value of V

d (II). III. Photograph of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

95]. (Reproduced with permission from [

95]).

Figure 10.

(

a) I. Schematic of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

90] at relaxed state (the left) and accommodated state (the right) II. Top view of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

90]. III. Lateral view of a prototype adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

90] at electrical rest(top) and under maximum actuation (bottom). (© IOP Publishing. Reproduced with permission from [

90]. All rights reserved). (

b) I. Schematic of the varifocal solid lens proposed in [

55]. II. Schematic lateral sectional view of the lens proposed in [

55] at electrical rest (top) and under actuation (bottom). III. Photograph of the varifocal solid lens proposed in [

55]. (Reproduced with permission from [

55]). (

c) Structure and operation principle of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

95] with no voltage (I) and with a voltage value of V

d (II). III. Photograph of the adaptive varifocal solid lens proposed in [

95]. (Reproduced with permission from [

95]).

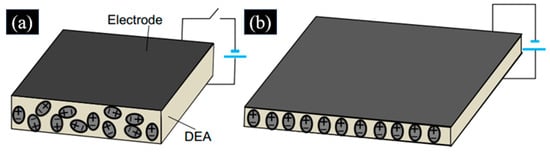

The DEA-based soft varifocal solid lens needs stretchable, robust, and highly conductive electrodes [

97]. Grease or particulate electrodes for DEAs are not stable and difficult to pattern for a miniaturized varifocal lens. Therefore, Lau et al. proposed a DEA-based varifocal solid lens with inkjet-printed and patterned silver nanoparticles as electrodes, which had better stretchability and conductivity than metal electrodes [

97]. Some conductive gel can act both as a lens and electrodes of DEA, so it has been a better choice to use the conductive gel as the electrodes of the DEA-based varifocal solid lens [

88,

98]. Liu et al. proposed a new self-contained varifocal lens based on transparent and conductive gels, as shown in

Figure 11a [

98]. The convex gels can be used as both lenses and actuator electrodes, whose desirable curvature was precisely patterned by inkjet 3D printing, making the lens system an unprecedented compact structure. The lens had a large focal length variation of 32–81% and a fast response speed of 80–153 ms. Zhong et al. proposed a solid tunable lens driven by a DEA based on a polyelectrolyte elastomer, as shown in

Figure 11b [

88]. The polyelectrolyte elastomer was directly synthesized by a mold-free technique on a DE membrane, which was used as both a lens and actuator electrode. It compacted the structure and simplified the fabrication procedure of the adaptive varifocal lens.

Ren et al. proposed a DEA-driven solid lens module that tunes the focal length by changing the position of the lens, as shown in

Figure 12 [

99]. A solid lens was tightly attached within a through-hole of a DE film with electrodes on the left side of the DE and no electrodes on the right side. When a voltage was applied to the electrodes of the DE, the expansion and contraction of the DE caused the solid lens to move to the right along a direction perpendicular to the optical axis. Since the shape of the lens did not change, the optical properties did not deteriorate. When combined with a solid lens, it becomes a lens group that can change the focal length by changing the position of the lens. When the driving voltage was 5.5 kV, the lens shift displacement was about 1.7 mm, and it took about 3.5 s to reach displacement stability.

The variable focal length range is an important indicator for an adaptive varifocal lens. For the varifocal solid lens in static conditions, the achievable range of focal length changing is mainly determined by three factors: the compliance of the lens, the area of the compliant electrodes, and the driving electric field [

90]. While dynamically tunable optical systems can achieve a wider range of focal length [

89,

100]. Kyung et al. proposed a dynamic varifocal solid lens driven by DEA [

100]. The lens consisted of a plano-convex PDMS lens as an aperture and a DEA. The DE bent upward when a voltage was applied to the electrodes, causing dynamic translational movement of the aperture in the vertical direction. It means the focal point of this lens can be dynamically adjusted by parallel movement in the vertical direction when the applied voltage changes, as shown in

Figure 13a. The focal length of the lens can be varied by 18.4%. The response time was less than 1 ms, and it was highly repeatable. Building on the foundation above, Kyung et al. proposed a DEA-based varifocal solid lens module for a dynamically varying focal system, which consisted of two parallel plano-convex and plano-concave lenses, as shown in

Figure 13b [

89]. Each active lens in the lens module consisted of a thin DE membrane with annular silver nanowires (AgNWs) electrodes, a hemispherical DE lens structure, and ground layers with a thin annular gold electrode. When a voltage was applied to the electrodes, the active lenses can produce electrically bi-directionally controllable and large translational movement ranging from −3.0 mm to 3.0 mm. A hybrid driving force was produced by silver nanowires and gold layers as well as the electromechanical pressure was produced from DE. The movement produced by the hybrid drive of the DE drive and electrostatic drive was as high as 230% of the movement produced by the DE drive alone. Based on the inverse mechanism of the expansion-tunable lens, Kyung et al. proposed a varifocal solid lens module consisting of a soft lens coupled with a radially expanding DEA pair, which can achieve a wider range focal length, as shown in

Figure 13c [

96]. The lens had a large focal length range since an expansion-based approach took advantage of larger focal length tunability over the contraction-based counterpart. The plano-convex soft lens in the middle of the ring was effectively stretched when the disk-type DE was driven by voltage, thus changing its focal length. Under the 5 kV driving voltage, the module operated with a focal length range of 65.7%. The soft lens had a diameter of 3 mm, and the focal length of the lens had a focusing range from 14.3 mm to 23.7 mm as the applied voltage increased from 0 to 4.6 kV.

2.7. Adaptive Varifocal Alvarez Lenses Base on DEA

Different from the conventional varifocal lens that changes the focal length through the axial movement of the lens group, the Alvarez lens is a novel kind of adaptive varifocal lens rediscovered by Alvarez and Lohmann, which can achieve a large focal length change through a small lateral movement [

111,

112,

113].

The Alvarez lens consists of two-phase plates with non-rotationally symmetric complementary cubic surface profiles, and the focal length is changed by the movement of the plate’s lateral perpendicular to the optical axis. The existing actuator to produce the lateral translation for the Alvarez lens includes MEMS-driven units, motors, and manual movement platforms [

114]. Compared with the actuator described above, the DE has many advantages, such as large displacement, quick response speed, low cost, and absence of noise pollution [

115,

116]. Continuous optical zoom of the Alvarez lens can be achieved by using DE, so DE has been a better choice of soft actuator [

114,

117,

118,

119,

120].

The principle of the Alvarez lens is not difficult to understand; the profiles of the two-phase plates can be described by the following equations [

111,

112,

113]:

where A, D, and E are constants to be determined as well as x and y is the transverse coordinate normal to the z-direction, and t1 and t2 are the phase profile of the Alvarez lens. A is the vector height modulation coefficient of the free-form surface, which controls the focal power of the Alvarez lens on the surface of a given area by controlling the height difference between the peaks and valleys of the surface; D is the influence factor of wedge quantity; E is the thickness of the center of each lens, ensuring that the thinnest part of the lens has sufficient mechanical strength.

Assuming the lateral displacement is δ, the focal length of the Alvarez lens (

f) can be expressed as:

where n is the refractive index of the Alvarez lens material.

According to Equation (6), when

δ = 0, the focal power of the Alvarez lens is 0, which is similar to a parallel plate. When

δ > 0, the focal power of the Alvarez lens is greater than 0, which is similar to a plano-convex lens with positive focal power; when

δ < 0, it resembles a plano-concave lens with negative focal power, as shown in

Figure 17 [

121].

The varifocal function can be achieved by applying actuation on the compliant electrodes of the DE adhered to the Alvarez lenses. The varifocal principle of the Alvarez lens actuated by the DEA is shown in

Figure 18. Two-phase plates were mounted on two DE film surfaces, respectively, to form the Alvarez lens [

114]. When no voltage was applied to the compliant electrode, the Alvarez lens was similar to a parallel plate; as shown in

Figure 18a, the focal length of the lens was infinite. When a driving voltage was applied to the compliant electrode, the DE was radially compressed by Maxwell’s stress, then made the phase plate move laterally towards the edge. Applying voltage to different electrodes can change the direction of phase plate movement, as shown in

Figure 18b,c [

114].

Alvarez lenses based on DEA can be fabricated to achieve continuous optical zoom compound eye imaging [

119], ultra-wide varifocal imaging with a selectable ROI [

120], continuous high-magnification zoom imaging [

114], two-dimensional varifocal scanning [

118,

122], and thin wide range varifocal diffraction [

117]. The optical systems using the Alvarez lenses have potential applications in large field-of-view imaging, machine vision, consumer electronics, virtual reality, endoscopy, and microscopy in the future.

Our group’s work focuses on preparing lenses driven by DEA, including Alvarez lenses. We proposed a continuous optical zoom imaging system based on Alvarez lenses actuated by DEs consisting of two Alvarez lenses and a solid lens, as shown in

Figure 19a [

114]. The 10× proposed optical zoom imaging system can achieve a large continuous magnification from 1.58× to 15.80× with a response time of 150 ms at 1.0 mm lateral displacement. The presented Alvarez lenses actuated by DEA, which had a variable focus function based on an Alvarez lens structure and DEA, as well as a scanning function based on the DE-based four-quadrant actuators, as shown in

Figure 19b [

120]. Based on the proposed lens elements, an imaging system was built to achieve ultra-wide varifocal imaging with a selectable region of interest by our group. The focal length variation in the proposed varifocal component was up to 30.5 times, where the maximum focal length was 181 mm, and the minimum focal length was 5.94 mm. We proposed a novel two-dimensional varifocal scanning element actuated by DE, which consisted of two pairs of Alvarez lenses and a pair of decentred lenses, as shown in

Figure 19c [

118,

122]. The focal length variation was up to 3.75 times, where the maximum and minimum focal lengths were 19.5 mm and 5.2 mm, respectively. The maximum scanning angle was 14.18°. The rise and fall response times were 124 ms and 203 ms, respectively. We also proposed a continuous optical zoom compound eye imaging system based on Alvarez lenses consisting of a curved Alvarez lens array (CALA) and two Alvarez lenses, as shown in

Figure 19d [

119]. By adjusting the focal length of the CALA and the two Alvarez lenses, the proposed system can achieve continuous zoom imaging without any mechanical movement vertically to the optical axis. The experimental results showed that the paraxial magnification of the target can range from ~0.30× to ~0.9×. The overall dimensions of the optical imaging part were 54 mm × 36 mm × 60 mm (L × W × H). The response time was 180 ms. Moreover, the FOV of the proposed lens was 30°. We designed a thin, wide range of varifocal diffractive Alvarez lenses actuated by DEA, as shown in

Figure 19e [

117]. The focal length ratio was up to 10×, where the maximum the minimum focal lengths were 300 mm and 30 mm, respectively. The rise time and fall time were 134 ms and 206 ms. As it is difficult to process the complex free-form surface of the Alvarez lenses, we proposed a planar liquid crystal varifocal Alvarez lens based on DEA by combining the Alvarez varifocal principle with liquid crystal materials, as shown in

Figure 19f [

123]. Compared with the varifocal liquid crystal lenses with a similar aperture, the proposed lens can change the focus length by simply actuating the two-phase plates to move laterally without changing the arrangement of the liquid crystal molecules. The proposed liquid crystal Alvarez lens based on DEA can achieve a varifocal range from 1476 mm to 118 mm at a lateral displacement from 0.2 mm to 2.5 mm. The rise time and fall time were 185 ms and 296 ms, respectively.

Figure 20 shows the relationship between the F-number and lens diameter of some adaptive varifocal lenses. (The F-number is calculated by dividing focal distance by lens diameter).

Table 1 lists the parameters of adaptive varifocal lenses based on DEA. The response time of the lenses directly influences the imaging speed. The focal length range is also an important performance parameter in optical varifocal imaging systems. A wide varifocal range and a high varifocal ratio are supposed. The focal length range of some lenses is described by the object distance range for clear imaging. The driving voltage of adaptive lenses is another important performance parameter in optical varifocal imaging systems, which is influenced by the material of DEA and compliant electrodes. A low driving voltage is supposed. The functional principle shows how it changes the focal length.