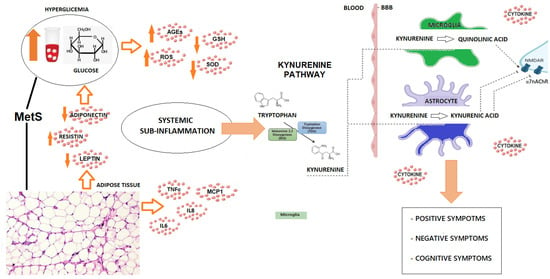

Patients with schizophrenia frequently present with comorbid MetS, with a prevalence exceeding 40% [9]. This association is linked to systemic low-grade inflammation driven by visceral obesity, hormonal dysregulation, and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines [4,9,10,11,12]. MetS correlates with greater cognitive impairment in schizophrenia [2,44], potentially due to enhanced neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, cytotoxicity, white matter (WM) disruption, and microglial activation [5,6,13,14,15,45,46]. All these pathogenic elements have a negative impact on the cognitive outcome. Indeed, patients with MetS exhibit lower cognitive performance across multiple cognitive domains [2,44]. Interestingly, the relationship between individual MetS components and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is well documented [44,47], though with small effect sizes [48]. Reverse causality is possible, where cognitive deficits, but also negative symptoms, may contribute to MetS through socioeconomic disadvantage, unhealthy lifestyles, less access to healthcare, carelessness, and sedentary behavior [49]. Second-generation antipsychotics, known for inducing weight gain and metabolic abnormalities, further compound MetS risk [50]. Indeed, Mitchell and colleagues compared un-medicated patients, first-episode psychoses, and patients on stable antipsychotic treatment and found that the prevalence of MetS drastically increases if antipsychotics are prescribed [51]. The KP may mediate the link between systemic inflammation and cognitive decline through neuroactive metabolites, which are formed under inflammatory conditions [5]. Some findings suggest a relationship between MetS and pharmaco-resistance, although the causal link may be bidirectional, as refractory symptoms are typically treated with higher doses of antipsychotics, particularly clozapine, which is associated with significant weight gain, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance [50]. Conversely, the pro-inflammatory state induced by MetS and subsequent activation of the KP may partially explain the more severe refractory symptoms observed in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS). As a matter of fact, obesity, altered metabolism, and systemic low-grade inflammation correlate with an increased KYN/Trp ratio, reflecting greater Trp catabolism through the KP and elevated levels of its metabolites [52,53,54,55,56]. Therefore, peripheral inflammation driven by the dysmetabolic state may lead to enhanced concentrations of KYN in the brain through inter-organ crosstalk involving adipose tissue, skeletal muscles, the gut, and the CNS [55,56,57].

Source link

Jacopo Sapienza www.mdpi.com