1. Introduction

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in US feedlots, developing from intricate interactions between pathogens, stress, and host factors [

1,

2,

3]. This complex syndrome contributes approximately 70–80% of total morbidity and 10–50% mortality in US feedlots [

2]. Cattle are exposed to varying degrees of stress surrounding feedlot entry including weaning, comingling, dietary transitions, and transportation. Viruses commonly isolated from affected animals include bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), and bovine herpes virus 1 (BHV-1). Bovine coronavirus is known to cause calfhood diarrhea; while its role in BRD is not fully understood, research supports a trophism for respiratory tract epithelium in cattle [

4,

5]. Four bacteria typically isolated from morbid animals and respiratory tissues of deceased animals include

Mannheimia haemolytica,

Pasteurella multocida,

Histophilus somni, and

Mycoplasma bovis [

2].

At this time, BRD diagnosis is primarily focused on a visual exam identifying signs of depression, inappetence, and abnormal respiratory rates; however, cattle are prey species and will attempt to mask illness from predators [

1,

2,

3]. Antemortem diagnostic methods, such as nasal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage, and transtracheal washes, reflect individual animals and require labor, time, and animal restraint.

Aggregate sampling allows for a concurrent collection of multiple individuals, providing a broad overview of health trends. In veterinary medicine, this approach minimizes the need for invasive procedures on individual animals, thus reducing stress, ensuring safety, and improving animal welfare. Swine veterinarians frequently use aggregate samples, such as oral fluids, as an effective diagnostic tool in the detection and surveillance of respiratory viruses [

6,

7,

8]. Similarly, viruses and bacteria can be detected by sampling bulk milk tanks in dairies [

9,

10]. In human medicine, wastewater is a valuable surveillance substrate to regionally detect illicit drug use and infectious diseases, such as COVID-19 [

11,

12]. Additionally, environmental samples, such as bioaerosols, have been utilized for respiratory virus detection in swine and poultry farms, and even military barracks [

13,

14,

15]. Pen-level sampling in confined cattle was previously explored using ropes and fecal samples to detect

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella spp. [

16,

17]. However, there are currently no aggregate sampling techniques to detect bovine respiratory disease [

8,

18].

In the US feedlot industry, management decisions are often made at the lot or pen level. The ability to detect pathogens at the pen level could lead to improved accuracy in BRD case definition, enhanced precision of antimicrobial therapies, and superior treatment outcomes. Additionally, the success of an aggregate diagnostic tool could be critical in the detection of emerging viruses, foreign animal disease, and zoonotic pathogens.

The objectives of this pilot study are to determine if the water trough can serve as an aggregate sample substrate to detect pathogens associated with bovine respiratory disease and to describe the viral, bacterial, and antimicrobial resistance profiles over time.

3. Results

Ten pens were enrolled and sampled in this study. Overall, the average calf weight at placement was 675.0 lbs. ± 128.1 (306.7 kgs ± 58.2). In the first 100 days on feed, the respiratory morbidity per pen ranged from 0.7–50.8% of animals affected. Total mortality ranged from 0.6–9.7%. The average number of animals per pen was 157 ± 22. The observed respiratory morbidity was further divided post hoc into three categories: low, moderate, and high for morbidity < 15%, 16 to 30%, and >31%, respectively. This division is based on the average respiratory morbidity reported in US feedlots [

26]. Placement weight, respiratory morbidity, and total mortality are presented in

Table 1.

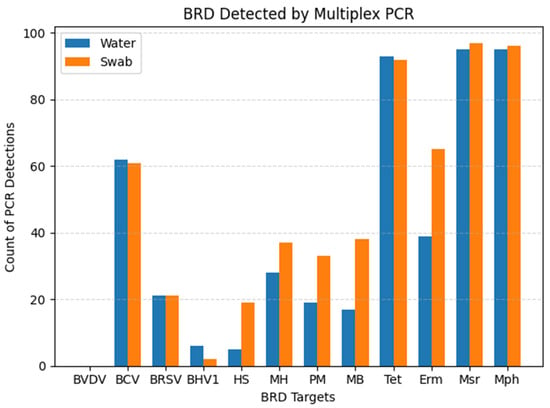

All ten pens received tylosin in the feed for reduction of liver abscesses. Nine out of ten pens received chlortetracycline in the feed for the treatment of respiratory disease. Six out of ten pens received an injectable antibiotic at the time of initial processing, known as metaphylactic control of respiratory disease. Six pens were heifers only, three pens were steers only, and one pen fed a mixed-sex group. The cumulative distribution of detected viral, bacterial, and AMR genes from each sample substrate can be visualized in

Figure 1.

Agreement between the sample substrates is depicted in

Table 2. The prevalence of each multiplex component varies, and thus wide ranges of PPA and kappa are observed. The overall PPA and kappa are 84.01% and 0.72, respectively. Bayesian latent class analysis generated wide ranges of sensitivity and specificity (

Table 3). The highest mean sensitivity was observed for BCV, BRSV, and all four AMR genes. Viral and bacterial organisms reached peak sensitivity values on days 4–21 and peak specificity values on days 35–56 (

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). For example, BCV reached 79% sensitivity on day 7 and a specificity of 55% on day 42.

Mannheimia reached a peak sensitivity of 67% on day 4 and a peak specificity of 79% on day 56. All four AMR genes’ sensitivity and specificity remained relatively constant throughout the sampling period. BVDV was not detected in this dataset and was excluded from further Bayesian analyses.

Fisher’s exact test was used to determine if there was a significant association with total PCR viral and bacterial detections and observed morbidity categories. Statistical significance was declared if

p-values were ≤0.05. A significant association was detected for sample specimens (

p = 0.0139 water;

p = 0.0222 swab). Differences in PCR detections between low-morbidity pens compared to a higher-morbidity pen can be visualized in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The same pens are represented in each figure. These figures illustrate the fluctuation in PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values across time per viral, bacterial, and AMR multiplex PCR panel. The respective cumulative pen morbidity percent is overlayed on each subplot, using the same

y-axis scale. Minimal viral and bacteria are detected from the low-morbidity pen compared to the high-morbidity pen; however, AMR genes are detected in both pens. Overall, the moderate and high-morbidity pens displayed similar trends of pathogen prevalence and cycle threshold values.

Relationships between diagnostic results, pen demographics, and sampling day were further investigated in multiple individual analyses. To account for repeated measures, mixed-effects logistic regression was used to analyze the association between PCR detections and sampling days. Generalized linear mixed-model regression analyses were used to explore the relationship of morbidity and pen demographics. These analyses were deemed unsuitable due to small sample size, unreliable estimates of random effects, and poor model convergence.

4. Discussion

The results of this pilot study investigate the plausibility of using the water tank as an aggregate sample substrate in pens of confined cattle. Viral, bacterial, and AMR components of BRD were detected throughout the first 60 days on feed in varying degrees. PCR detections differed significantly among observed morbidity categories (

Table 1; Fisher’s exact

p = 0.0139 water;

p = 0.0222 swab).

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate the comparison between a low morbidity to a high morbidity pen in relation to PCR detections from viral, bacterial, and AMR panels. In this dataset, detections of viral and bacterial pathogens occur early in the feeding period (≤21 DOF) as visually observed morbidity increases. Pathogen detections tended to plateau before decreasing to an undetectable level as the feeding period progressed (≥42 DOF) and morbidity plateaued. AMR genes tended to be detected early and remain detected throughout the sampling period. Peak sensitivity ranges (21–79%) observed early in the feeding period suggest the probability of detection is greatest from days 4–21.

The presence of viral and bacterial nucleic acids does not necessarily indicate active infections. It is possible the viral detections, apart from coronavirus, are influenced from the use of parenteral, modified live vaccines in these animals [

27]. However, all pens received equivalent vaccines and the low-morbidity pens did not demonstrate similar viral detections as the high-morbidity pens. In addition, the detection of AMR genes in these samples does not necessarily indicate that they originated from BRD pathogens as the genes are potentially mobile and can be found in other organisms [

23]. However, these genes are consistently found in BRD pathogens and have high predictive values in bovine lungs for the isolation of phenotypically resistant

Mannheimia [

23]. Specimens included in the multiplex PCR may or may not be representative of the true microbial dynamics in the water tanks. Water tanks have been examined in another study, which demonstrated profound diversity in bacteria and AMR profiles using whole genome sequencing [

28]. The water tanks represent a focal area of the pen that each animal visits and contributes saliva and nasal secretions; however, the tank can also capture environmental dust, manure, feed particles, etc., from which the AMR genes could originate, as these genes are associated with BRD pathogens, but are not necessarily specific to them. For this reason, it is possible that wildlife, such as birds, could contribute to AMR gene detections. These factors potentially explain the AMR prevalence from the low-morbidity pens in

Figure 4. Nonetheless, this study illustrates a pattern of detection, or perhaps a manifestation of stress, while clinical observations of morbidity accumulate. Further research is needed to understand the magnitude of these trends.

The agreement between the water sample and tank swab was explored with Percent Positive Agreement, kappa, and Bayesian latent class estimates of sensitivity and specificity. The overall agreement between the water and swab samples varied depending on what was detected (viral, bacterial, or AMR genes) and when. Percent Positive Agreement ranged from 17.39% to 99.48%. Kappa results ranged from 0.104 to 0.884. The overall PPA and kappa are 84.01% and 0.719, respectively. A more uniform cattle population may improve precision in these estimates.

There is no gold standard in evaluating aggregate diagnostic samples in bovine medicine [

18,

29]. There is also no gold standard for the clinical diagnosis of BRD [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Therefore, Bayesian latent class analysis was applied to estimate sensitivity and specificity of each substrate’s ability to detect pathogens. This methodology provides a rigorous approach to assessing diagnostic test accuracy in the absence of a gold standard [

34,

35], offering insights into the utility of water samples for detecting pathogens and estimating pathogen shedding levels in the field. The Bayesian latent class analysis framework allows for the estimation of test accuracy without relying on strong prior assumptions, thereby accommodating the exploratory nature of the pilot study. Sensitivity and specificity reflect prevalence, which can be dynamic over time [

24]. Thus, sensitivity and specificity estimates vary across sampling days and from organism to organism; nonetheless, overlapping confidence intervals suggest comparable performance between water and swab samples.

Most published Bayesian analyses use informative, prior beta distributions based on expert panel opinions and previous studies. A previous study estimated the sensitivity of visually observed clinical illness in beef cattle to be 57.5–62.2% and specificity to be 62.7–62.9% [

30]. This study also estimated the sensitivity of lung lesions at harvest to be 77.4–84.7%. These results suggest 38% of truly diseased animals are missed, and approximately 37% of calves without disease are treated as such [

30]. Another study found similar results in dairy calves using thoracic ultrasound (sensitivity 79.4%; specificity 93.9%) and clinical respiratory scores (sensitivity 62.4%; specificity 74.1%) [

32]. Other studies have estimated the sensitivity and specificity of visually observed clinical illness to be 27% and 92%, respectively [

33].

These studies reflect the complexity of identifying BRD in the field without the aid of diagnostics. Clinical signs typically used to identify morbid animals are subjective and not pathognomonic for respiratory disease. Without pragmatic, objective criteria, such as diagnostics, accuracy in BRD case definitions and the assessment of causal agents remain challenging.

Limitations

Given the nature of a longitudinal pilot study, many limitations exist. A robust comparison to conventional individual animal sampling, such as nasal swabs, would aid in the analysis and interpretation of these results. In addition, the sample size is underpowered to draw conclusions of the effect of viral and bacterial prevalence. Mixed models yielded unstable estimates or failed to converge, creating unreliable results. Conditional dependence may also exist that was not accounted for. Overall, sensitivity reflects the probability of detection. Further, enrolled pens were not randomly selected to intentionally include low and high-risk pens. This created variation in prevalence, which is reflected in the results. Sensitivity, specificity, and confidence intervals would likely improve with a more uniform cattle population. Additionally, any dilution effect within the tanks is largely unknown and not considered in this study. Seasonal effects and pathogen longevity are also unknown with this technique and require additional research.