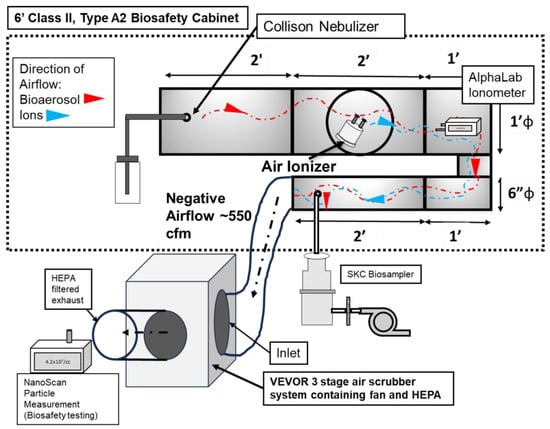

3.2. Measurement of Ion Concentration Inside Duct

The concentration of ions produced by the ionizers inside the experimental duct was measured with an ionometer. For each individual ionizer, two sets of ion level measurements were conducted. The results are presented in Table 1. For ionizer device A, the concentration of ions without any presence of bioaerosol was 2.836 (±0.16) × 105/cc. This was reduced to 2.546 (±0.31) × 105/cc in the presence of bioaerosol. This represents a 10% ion loss in the presence of bioaerosol, albeit not statistically significant (p = 0.2233). The temperature and humidity during the experiments was 21 °C and 42%, respectively. No significant change in either temperature or RH was observed during ion measurements. For device B, without the presence of any bioaerosol, the concentration of ions produced was 1.578 (±0.15) × 106/cc. This reduced to 1.116 (±0.05) × 106/cc in the presence of bioaerosol produced by the nebulizer and introduced into the system. Here, the reduction in levels of ions was higher and statistically significant, as compared to device A, with a 29.2% reduction in presence of the aerosol (p = 0.0072). The temperature and humidity during the experimental rating of the ionizer B were 20 °C and 45%, respectively. For both ionizers, the temperature varied by <±1 °C and the relative humidity varied by <±1.5%. This variation was not considered statistically significant. The reductions in the concentrations of ions can be attributed to collisions with aerosol particles. Ozone was below the detection limit of the measurement device (3 ppb).

3.3. Bacteriophage MS2 Inactivation

The results of the bacteriophage MS2 inactivation testing with Ionizer A exposure are shown in Figure 2a. The control (no ionizer exposure) air samples contained 1.1 × 104 (±2.46 × 103) pfu/liter of air of bacteriophage MS2. The air samples exposed to ions generated by ionizer A contained 1.98 × 103 (±3 × 102) pfu/liter of air. This translates to an 82.02% (0.745 log10) reduction (p = 0.0032). The temperature and relative humidity were measured to be 21 °C and 56%, respectively.

The results of the bacteriophage MS2 testing with Ionizer B exposure are shown in Figure 2b. The control (no ionizer exposure) air samples contained 4.23 × 104 (±2.48 × 104) pfu/liter of air of bacteriophage MS2. The air samples exposed to ions generated by ionizer B contained 7.73 × 103 (±1.09 × 103) pfu/liter of air. This translates to an 81.72% (0.738 log10) reduction (p = 0.0743). The temperature and relative humidity were measured to be 20 °C and 69%, respectively.

The results from the bacteriophage MS2 inactivation indicate significant inactivation for ionizer A, with p < 0.05. For ionizer B, the results are significant only to the 0.05 < p < 0.1 level; however, the scientifically meaningful nature of results can be attributed to the fact that contact time for the ions and the airborne virus is 0.625 s. This residence time was calculated according to the effective airflow in each section of the duct, between the ionizer section where the ions were generated and the bioaerosol sampling port, where the bioaerosol exited the duct. Since this is a single pass system and the effective flow rate was high (298 cfm), the residence time was quite short. According to ASHRAE standards, the required flow rate for indoor spaces is 15 cfm/person [38,39]. Hence, the flow rate utilized here corresponds well to the HVAC duct of a 20-person occupancy room, where one would expect such short residence times.

There have been few studies that have investigated the efficacy of technologies against airborne bacteriophage MS2. As the experimental parameters (such as the flow rate, residence time, and power consumption) vastly differ for studies on ionizers, direct comparison of the inactivation efficiencies is difficult. A study was conducted by Hyun et al., to determine the efficacy of corona discharge-generated bipolar ions. The experimental setup utilized by them included a test duct with a 0.04 × 0.04 m2 cross-sectional area and a length of 1 m. This was a design similar to that of the present study. The ionization plasma source was installed inside the duct, and bioaerosol of MS2 was exposed to it. The difference in methodology, however, was that in their study, much larger contact times, of 15 and 30 min, were utilized [17]. This was primarily due to the effective flow rate utilized by them being magnitudes lower than the one utilized in the present study. Wu et al. exposed airborne MS2 to atmospheric pressure cold plasma, which is known to generate ions, and for a short exposure time of 0.12 s, 80–95% inactivation of MS2 was reported, corresponding to 20–28 Watts of plasma power. Although this amount of inactivation is similar to the numbers seen in present study, the power utilized by their system is higher than that of the ionizers tested here [40]. Another study utilized nanosilver/TiO2 filters with a negative air ionizer and discovered that the highest efficacy could be found with a combination of two technologies, for a 97% removal of bacteriophage MS2 aerosol [35]. For ozone-based inactivation, a study reported that a dose of 3.43 ppm was required to inactivate 90% of MS2 bioaerosol, with 13.8 s contact time, thus emphasizing that ozone produces much slower inactivation as compared to the ions presented here [41]. In terms of UV as an intervention method, in an earlier study by the authors, a commercially available UV-based 222 nm device was found to produce a 90% reduction in the concentration of airborne HCoV-229E after 7.2 s of residence time [9].

When considering nanotechnology-based methods, the authors have developed a novel nano-carrier aerosol called Engineered Water Nanostructures (EWNS) for inactivation of viruses in air. In an earlier study, EWNS generated with nanogram levels of hydrogen peroxide produced a 94% reduction in the concentration of airborne H1N1/PR/8 Influenza virus [16]. The EWNS nano-carrier technology has also been shown to be effective against mycobacteria, as it produced a 68% reduction in the concentration of airborne Mycobacterium parafortuitum (a surrogate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis) after exposure to 36,000 particle of EWNS/cc [42]. Earlier mechanistic studies which evaluate ionizers and related ion generating cold plasma devices have pointed out ions, as well as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ozone to be the major inactivating agents [11,43,44]. Here, in this study, ozone can be eliminated as the ozone generated was lower than the detection limit of the monitors utilized, i.e., lower than 3 ppb. This points to ions and ROS as potential inactivating agents. Further investigation into the exact mechanism is warranted.

It should also be considered here is that String et al., in their study of the various surrogates utilized for SARS-CoV-2 found that the bacteriophage MS2 is more difficult to inactivate, as compared to the SARS-CoV-2 [27]. This is not surprising, given that SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped virus and MS2 is a small, non-enveloped virus, and it is generally accepted that enveloped viruses are more highly susceptible to chemical inactivation than small, non-enveloped viruses [45]. Thus, it is suggested that the efficacies of the ionizer devices tested in the present study are expected to be even higher when challenged with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Source link

Nachiket Vaze www.mdpi.com