1. Introduction

In recent years, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the dangerous expansion of conflict in the Middle East, war has returned to the center of the news and contemporary political debate, along with its harmful humanitarian, economic, social, and psychological consequences (

Behnassi & El Haiba, 2022;

United Nations Organization, 2022a,

2022b). In a postmodernity already characterized by a hyper-acceleration of change (

Allam et al., 2022;

Ajad & Kumar Tiwari, 2022;

Berhe, 2022;

Carta et al., 2022) and collective phenomena of traumatic impact—such as economic crises, pandemics, and climate change—war emerges as a potential cumulative factor of traumaticity (

Khan, 1963/1974) that undermines the socioeconomic fabric of states, the sense of security, community belonging, and social bonds (

Murthy & Lakshminarayana, 2006;

Hirschberger, 2018).

On the European continent, after 70 years of peace and prosperity, the return of war occurred while people were still grappling with the economic, health, and psychological effects of the pandemic trauma (

Anand et al., 2020;

Horesh & Brown, 2020;

De Rosa & Regnoli, 2022;

Regnoli et al., 2022;

Talevi et al., 2020), slowing the recovery process (

Orhan, 2022). With the Russian–Ukrainian war, a new historical period has begun (

Sheather, 2022), marked by humanitarian and economic crises (

Ajad & Kumar Tiwari, 2022;

BBC News, 2022;

The Lancet Regional Health-Europe, 2022), and the re-emergence of the nuclear power as a threat, fueling anxieties, fears, and worries far beyond the geographical areas directly involved (

Riad et al., 2023;

Surzykiewicz et al., 2022). In this scenario of uncertainty, the past year has seen a dangerous escalation in the Middle East, with a tragic legacy of destruction, death, and injury, particularly among civilians (

ISPI, 2023); the reappearance of previously eradicated diseases; and a food crisis that has turned Gaza into a genuine humanitarian emergency (

Hussein & Haddad, 2024;

United Nations Organization, 2024), with the potential to spread to Lebanon.

The impact of wars has mainly been analyzed in terms of their degree of destructiveness and the economic and territorial transformations they have produced (

Murthy & Lakshminarayana, 2006). The psychological and social consequences, however, are more difficult to capture. Nevertheless, wars are undeniably traumatic events due to their destructiveness, violence, and uncontrollability (

American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Psychological research has focused on the effects of conflict on directly affected communities, consistently highlighting its role in increasing post-traumatic, depressive, anxiety, and psychosomatic symptoms in different contexts (

Ahmad et al., 2000;

Bisson et al., 2015;

Calderoni et al., 2006;

Cardozo et al., 2000). The negative impact of war on the mental health of the population, especially children, adolescents, and young adults, has also been highlighted in recent studies conducted in the context of the Russian–Ukrainian war and in the Gaza Strip (

Kurapov et al., 2023;

Moreno-Chaparro et al., 2022;

Riad et al., 2023;

Veronese et al., 2022;

Stevelink et al., 2018;

Taha et al., 2024).

1.1. “Beyond the Bombs”: The Indirect Psychological Impact of the War

In 1917,

Armstrong-Jones (

1917) emphasized the importance of considering the effects of war even in contexts not directly involved, a point that is reiterated by

Taylor and Frazer’s (

1981) theory of multilevel trauma, according to which —beyond the individuals directly experiencing a traumatic event —specific individual characteristics, media coverage of the event, or identification dynamics with victims may play a role in the development of anxiety and post-traumatic symptoms in individuals or communities not directly involved in the trauma (levels 5 and 6). Although research in this area is still limited, psychological studies have increasingly examined the indirect effects of war since the invasion of Ukraine (

Scharbert et al., 2024). These studies, ranging from the cross-cultural study by

Chudzicka-Czupała et al. (

2023) to those conducted in Germany and Poland (

Hajek et al., 2023;

Kalcza-Janosi et al., 2023), have highlighted the extent to which the outbreak of conflict has fueled negative emotions and various forms of mental suffering, and how fear of war increases psychological distress, which, as noted above, particularly affects women and the youth population (

Hamilton et al., 1988;

Poikolainen et al., 2004).

Among the developmental targets at risk are young adults, who are already deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (

Balsamo & Carlucci, 2020;

Parola et al., 2020;

Regnoli et al., 2022;

Vanhaecht et al., 2021) and by pervasive worries about the future of the world (

Millenial Survey Deloitte, 2022). The pandemic has indeed contributed to exacerbate the psychological distress that characterizes this developmental target group (

Nastro et al., 2013;

Rosina, 2019), clearly highlighting the “psychic fragility” (

De Rosa & Regnoli, 2022) fostered over the years by the dominant cultural logics (

Benasayag, 2004;

Chicchi, 2021;

Kaës, 2014). The experience of the lockdown, the uncertainty and fear fueled by the uncontrollability of the pandemic’s progression, the reduction in social interactions, and the increase in socioeconomic difficulties in many households have deeply affected the mental health of young adults, leading to increased anxiety, depressive symptoms, stress-related problems, and concerns about their personal and societal future (

Lessa et al., 2021;

Parola et al., 2020;

Pierce et al., 2020;

Regnoli et al., 2022;

Salari et al., 2021;

Sisk et al., 2022). The increase in these forms of distress has resulted in a true mental health emergency in Italy (

Ansa, 2021) and highlighted how the pandemic experience has contributed to a particular vulnerability among young people to subsequent collective events of a potentially traumatic in nature, such as war and the climate crisis (

Barchielli et al., 2022;

Lessa et al., 2021;

Mottola et al., 2023;

Regnoli et al., 2024b,

2024c;

Xiang et al., 2020).

Consistent with findings from studies conducted in other contexts (

Hajek et al., 2023;

Kalcza-Janosi et al., 2023), recent research has shown high levels of fear of war among young Italian adults, which predicts higher levels of self-reported psychological distress (

Regnoli et al., 2023). Furthermore, studies have highlighted the mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty and an anxious view of the future in this relationship (

Regnoli et al., 2024a). Furthermore, war is currently highly present in media communication, especially through the dissemination of information, images, and videos that—by brutally depicting the destruction and suffering of populations in conflict—increase uncertainty, anxiety, and worry about war in various contexts (

Chudzicka-Czupała et al., 2023;

Gottschick et al., 2023;

Malecki et al., 2023;

Johnson et al., 2022). As previously highlighted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (

Garfin et al., 2020;

Mazza et al., 2020), the media explosion of distressing events, interacting with various individual characteristics such as a predisposition to anxiety or worry traits or a pessimistic view of the future, can exacerbate psychological distress in young adults (

Papageorgiou & Pitsaki, 2017;

Vasterman et al., 2005). For this reason, discussing war in contexts not directly involved in conflicts has become a current necessity, as evidenced by the European Commission (2022) and several recent studies conducted in Italy (

Barchielli et al., 2022;

Bezzi, 2022;

Mottola et al., 2023), which found that the European population is most concerned about the escalation of conflicts, their negative economic consequences, and the possible involvement in a nuclear war.

1.2. From the Complex Mental Process of Worrying to the Worry About War

When faced with an event or problem that is perceived as stressful, threatening, and whose outcome is unpredictable, uncertain, and/or negative, the mental process of worry is crucial for understanding and defining the stressor and selecting strategies for coping with it (

Borkovec et al., 1983). It is defined as “a chain of thoughts or images burdened with negative emotions […] that is relatively uncontrollable” (

Borkovec et al., 1983, p. 10), the result of appraising a stressor that, if perceived as threatening and as a harbinger of consequences—such as war—is likely to foster psychological distress (

Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Conceptualized as a mental process focused on negative verbal thoughts rather than images (

Meyer et al., 1990), research has gradually differentiated the construct of worry from anxiety and fear, despite its strong associations with and role in anxiety and depression (

Borkovec et al., 1998;

Davey, 1993;

Goodwin et al., 2017).

As reflected in the definition, all individuals experience worry as an adaptive process that supports problem solving, focuses attention on the perceived problem/threat, and implements action (

Davey, 1993). It takes on a disabling function when it becomes an uncontrollable and persistent process that negatively affects everyday life, interferes with problem solving, and promotes avoidance and procrastination strategies (

Holaway et al., 2006;

Szabó & Lovibond, 2002). Research has shown that not only in its maladaptive function, but also as everyday worries—worries driven by daily and contextual stressors—worry can impair psychological well-being, fueling anxiety, stress, depression, psychosomatic symptoms, dissatisfaction with life, and feelings of loneliness, particularly in the developmental target of young adults (

Borghi et al., 1986;

Goodwin et al., 2017;

Kawachi et al., 1994;

Chang, 2000;

Kelly et al., 2005;

Kelly, 2008;

Brosschot et al., 2006;

Thomsen et al., 2004).

In line with the aforementioned literature, Worry about War has been considered as a cognitive–emotional process, mainly characterized by verbal–linguistic thoughts (and less by images) about war and its possible effects in the immediate (present) and long-term (future). In line with the dual nature of worry (adaptive/disadaptive), worry about war, on the one hand, could lead to awareness of the phenomenon, information seeking, and the adoption of behaviors to support affected populations, but, on the other hand, it can also become a persistent and/or uncontrollable mental process that, in interaction with complex negative emotions, can lead to psychological distress; it is also a form of apprehension about the consequences that war has or could have on oneself, loved ones, and other peoples.

Although several studies have explored the relationship between wars, increased worry, and mental health (

Goldenring & Doctor, 1986;

Mottola et al., 2023;

Hamilton et al., 1988), to our knowledge, there are no instruments that specifically assess the worry about war. In general, only a few instruments are currently available to measure the indirect psychological effects of war (Fear of War Scale by

Kalcza-Janosi et al., 2023; ad. it.

Regnoli et al., 2023; War Anxiety Scale by

Surzykiewicz et al., 2022; War-related Stress Scale by

Vargová et al., 2024), especially when considering the Italian context. Therefore, as

Surzykiewicz et al. (

2022) argue, precisely because of the relevance of the field of investigation, there is a need for valid and reliable measures to investigate the negative effects of war in different cultural contexts, and to identify the most vulnerable targets. The present study attempts to address this need by developing a scale of the impact of war, as measured by the construct of worry, to fill the gap in the literature. Specifically, worry—due to its association with a more enduring reflective component (

Dugas et al., 1998;

Goodwin et al., 2017)—may be a more suitable construct than anxiety or fear for assessing the impact of collective phenomena such as war in contexts not directly involved in the conflict but still strongly influenced by its media, social, and economic effects.

1.3. Phases and Aims of Empirical Research Design

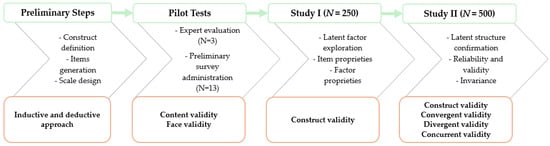

The present study describes the process of developing, validating, and evaluating the psychometric properties of the War Worry Scale (WWS), an instrument designed to assess worry about war in contexts not directly involved in war.

The first phase was devoted to the process of construct definition, item construction, and instrument design, followed by an evaluation of the relevance of the pool items by a panel of experts and a pilot test with a group of young adults to assess the clarity and comprehensibility of the generated items.

The first version of the WWS was then administered to a first sample of young Italian adults in order to examine the item characteristics, the dimensionality of the scale, and some preliminary psychometric properties (Study I). Subsequently, a second sample of young Italian adults was recruited in order to confirm the factorial structure that had emerged in the previous study, to test the internal consistency of the WWS, to explore the measurement invariance of the instrument with respect to gender, and to verify its convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity (Study II).

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the steps involved in the development and validation of the WWS.

5. Discussion

The present study describes the process of development and validation of the War Worry Scale (WWS), an instrument designed to assess the worry about war in non-war-torn environments, such as Italy. The development of the WWS aims to fill the gap in the literature regarding the lack of instruments to assess the indirect psychological effects of war. For this purpose, the construct of worry was chosen, which is defined as a chain of thoughts or images characterized by negative emotions (

Borkovec et al., 1983), resulting from the evaluation of a perceived stressor as threatening and heralding consequences (

Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In line with this literature and with

Taylor and Frazer’s (

1981) theory, worry about war has been defined taking into account that this phenomenon can be understood as an event that can have multilevel traumatic effects and can also affect the mental health of individuals and communities indirectly exposed to it. In order to study the effects of war in this type of context, the construction of appropriate and valid measures is seen as a need (

Surzykiewicz et al., 2022), to which this study aims to contribute. The final version of the WWS is presented in

Appendix A.

The items were generated from a content analysis (

Krippendorff, 1980) carried out on unpublished narrative material collected with a large group of young Italian adults (inductive approach). The selected narrative excerpts—in continuity with what has been highlighted in the literature (

Barchielli et al., 2022;

Bezzi, 2022;

Mottola et al., 2023)—highlighted the involvement of young adults in contemporary issues, and became fundamental for defining the content of the WWS items. At the same time, as recommended by

Boateng et al. (

2018), the item development and scale design took into account the literature review on the topics of interest and the comparison with other validated instruments related to the worry constructs or the specific domain (psychological impact of war). Expert evaluation and a pilot test with a small group of young Italian adults supported the assessment of the content and face validity of the instrument. Study I explored the latent structure of the WWS by integrating the exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The EFA suggested a two-dimensional structure, highlighting that all items were significantly consistent in defining the two factors, with factor loadings and communalities above the cut-offs considered (

Field, 2013). Items 1, 3, 7, 12, 13, 15, and 16 were removed because they did not meet the selected criteria.

The factorial structure emerging from the EFA was confirmed by the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted on an independent sample of young Italian adults in Study II. The results showed that the WWS can be considered a solid and robust measure in terms of statistical fit, reliability, and validity. CFA results showed a very good fit of the second-order structure with fit indices in line with recommendations in the literature (

Hu & Bentler, 1999;

McDonald & Ho, 2002). All items loaded in the hypothesized dimension were in line with the results of Study I.

Specifically, the first dimension, Worry about the Present, consists of five items that assess worry about war through items that focus on current worries about war and its intensity (e.g., “Worry about war very often occupies my thoughts”) and on the effects of war on those directly affected (e.g., “I worry when I think about the effects of the war on people living in places of conflict”). The second dimension, Worry about the Future, assesses worry about war through items that explore the consequences of wars for one’s future and loved ones (e.g., “I am worried that the war will compromise my future”) and the possible escalation of wars into wider and/or nuclear conflicts (e.g., “I am worried about the outbreak of a nuclear war”).

Measurement invariance (configural, metrical, and scalar invariance) across gender was confirmed. As recommended by

Cheung and Rensvold (

2002) and

Putnick and Bornstein (

2016) when comparing configural, metrical, and scalar invariance models, the alternative indices (ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA) were more considered, as the chi-squared statistic is often affected by the sample sizes of the groups, which in our case were also not homogeneous. The results show that the WWS is an instrument that can measure the same construct for Italian young adults of different genders (male and female). The invariance of the instrument allows for the comparison of the means of the two groups and opens the possibility for future comparative analyses, such as multi-group SEM analysis.

In terms of internal consistency, the results suggest that the WWS is a reliable instrument and that all items contribute significantly to the excellent internal consistency of the scale. Considering

Fornell and Larker’s (

1981) criteria, the instrument showed good internal validity and no multicollinearity between WWP and WWF.

Correlation analyses between the WWS dimensions and the Fear of War Scale support the convergent validity of the instrument. In particular, the positive correlation with the FOWARS, and more specifically with the Experiential dimension of fear, which is specifically referred to in the definition of the WWS items, highlights the relationship between the constructs of worry about war and the fear of war, in line with the literature (

Borkovec et al., 1998;

Davey, 1993;

Goodwin et al., 2017).

Correlation analyses between WW dimensions and resilience supported the divergent validity. In particular, the lack of correlation with resilience—a construct traditionally understood as a dispositional trait—highlights the good discriminant validity of WWS, which in contrast detects a specific worry driven by a macrosocial and contextual stressor perceived as threatening (

Boehnke et al., 1993;

Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Finally, correlation analyses between the WWS dimensions and the Dark Future Scale and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale supported the concurrent validity. This result confirms the findings highlighted in the literature, which, despite their differences, highlight the strong link that worry plays in anxiety and depressive symptomatology (

Davey, 1993;

Goodwin et al., 2017). At the same time, the results indicate that this positive and significant correlation is not particularly large. This finding is also consistent with the research on worry about climate change (

Stewart, 2021) and highlights the intrinsic nature of the construct of worry, which, in addition to its ability to affect psychological well-being (

Holaway et al., 2006), may also have an adaptive function in coping with stressors (

Davey, 1993). Furthermore, recent research suggests that the relationship between emotions and mental processes related to global collective phenomena and mental health outcomes should be explored in greater depth, taking into account the possible influence of additional variables (

Stewart, 2021). Finally, with regard to the relationship between WW and DFS, our findings are in line with recent studies that have highlighted the extent to which collective events fuel worries about the future (

Millenial Survey Deloitte, 2022) and a negative view of the future (

Regnoli et al., 2024a,

2024b).

Study II also analyzed differences in levels of WWS according to sociodemographic variables. Specifically, the analyses show that females are more worried about the war than males. This finding is in line with several Italian and European studies on the psychological impact of war (

Hajek et al., 2023;

Kalcza-Janosi et al., 2023;

Regnoli et al., 2024a). Higher levels of concern about the war are also found among young adults attending university, particularly in the humanities, than among people of the same age who are working. On the one hand, this finding suggests that young students are in the process of constructing their future and collective events—such as war, climate change, COVID-19—represent unresolved challenges to be faced (

Henkens et al., 2022;

Lass-Hennemann et al., 2024;

Martine, 2022); on the other hand, the university context could be a stimulus for learning about the impact of contemporary collective phenomena and this could fuel worry about war and worry about the future. These findings seem to be in line with what is clearly visible in the narrative excerpts collected in a preliminary sample of 200 young adults, reported in

Supplementary Material I, where a worry about contemporary traumatic events and their possible impact on the future emerges.

Furthermore, the highest levels of worry about the war were found in couples compared to single participants. This finding could be interpreted by considering that war—like other potentially traumatic contemporary phenomena (

Marks et al., 2021)—may influence couples’ future planning, particularly the decision to have children in a world perceived as “dangerous”.

The results also show that people who participate in peace organizations and have a left-wing political orientation have a higher level of concern about war. This finding seems to indicate that young adults who participate in peace activities, in line with the mission of the associations, have higher levels of worry about the impact of war in the present and future. Finally, our results suggest that political ideology may also play a role in worry about war. Despite these findings, future studies could deepen these findings by considering numerically more homogeneous groups and provide evidence to guide the construction of interventions to support the target group of young adults.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations must be acknowledged. Convenience sampling and self-report instruments were used, and known biases—related to individual characteristics and social desirability—may have influenced responses. To overcome these limitations, future studies could use representative samples. In addition, most of the participants were young adult students from Southern Italy. Although the research highlights how this age group is more invested in contemporary issues than others—which is why this target group was chosen—future studies could include a more diverse sample of young adults, involve more young workers, and consider different levels of education in more detail. The factorial structure and the invariance of the instrument were tested by considering young adults mainly from Southern Italy. Future studies could use the instrument with adolescents and the general population. This could be useful in order to make comparisons in Worry about War levels both in different age groups and in different areas of Italy. Furthermore, this study did not consider media exposure to war information as a sociodemographic variable. Exposure may indeed have an effect on war anxiety in young adults in non-war-torn environments. Future studies will address this limitation by considering media exposure as a variable of interest. Finally, other contextual variables could be considered because of their potential impact on worries about war, such as the role of the parents, which has already proven to be significant in the experience of COVID-19 (

Regnoli et al., 2022,

2025). On the one hand, parents could provide a safe space for discourse to mitigate anxieties about the future, but on the other hand, they could also fuel these concerns. For example, studies show how helicopter parenting, characterized by overprotection and control, can increase emerging adults’ anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty (

La Rosa et al., 2025), both of which are relevant to war-related concerns. Future studies could take this into account when assessing possible predictors of worry about war.

6. Conclusions

The present study increases the availability of a valid and reliable measure to detect the dimension of worry about war in contexts not directly involved in war. The different steps presented in this paper (

Figure 1) describe the process of developing and validating the War Worry Scale (WWS), a new instrument for exploring worry about war. The item construction process followed a rigorous integration of inductive and deductive approaches, and subsequent studies revealed the second-order structure of the WWS, factorial robustness, good internal consistency, invariance of the instrument between male and female, and good convergent, divergent, and concurrent validity. The good psychometric properties support the use of the WWS to assess worry about war in young Italian adults, responding to the growing need for valid and reliable psychometric instruments to measure the impact of war in contexts not directly involved in it (

Surzykiewicz et al., 2022). The WWS could be used to explore how contemporary wars affect the mental health of the Italian young adult population, taking into account different risk and protective factors that may play a role in this relationship. Given the growing involvement of young adults in contemporary issues, as highlighted in the literature (

Bezzi, 2022;

Millenial Survey Deloitte, 2022), the WWS could be a valuable tool to guide the design and implementation of targeted interventions to support the target population. Specifically, we believe that the WWS could be useful in individual clinical settings to assess war-related concerns, where appropriate, and thereby tailor psychological interventions to each individual’s unique needs. At the same time, we believe that this tool could also be a valuable aid in group interventions, where young people, under the guidance of an expert, can express, share, and discuss emotions, thoughts, and moods heightened by contemporary conflicts. These groups could provide a safe space for emotional expression while simultaneously supporting adaptive coping strategies, the maintenance of hope, and both individual and group empowerment (

De Rosa, 2023). In this regard, the WWS could be integrated into intervention programs aimed at raising awareness of the mental health issues that collective events such as war can generate, becoming a tool capable of stimulating reflection and discussion on these issues, and facilitating the identification of young adults most at risk of developing psychological distress. In this sense, the WWS could be a useful tool for the design of educational and psychological interventions and for the longitudinal evaluation of their effectiveness.