4.1. Validation of CMIP6 Models

According to the validation results of CMIP6 models in the Tacna region, it was found that the models perform better for minimum temperature, show moderate performance for precipitation, and exhibit weaker performance for maximum temperature. Some GCMs struggle to accurately capture the complex geographic features of regions like the Andes, which can result in incorrect temperature simulations, particularly with respect to elevation-dependent lapse rates [

53]. Regarding precipitation, the difference between observed data and GCM outputs may be explained by the limitations of GCMs, such as systematic biases, coarse spatial resolution, and the insufficient representation of climatic processes at regional scales [

54].

These results are consistent with recent studies that highlight the challenges climate models face in simulating temperature and precipitation, particularly in complex regions such as the Andes [

16]. According to [

48], annual cycles in the Tropical Andes Hotspot are not accurately captured by GCMs, particularly during the wet season; however, CMIP6 models show improvements, with reduced biases compared to previous generations. Moreover, according to [

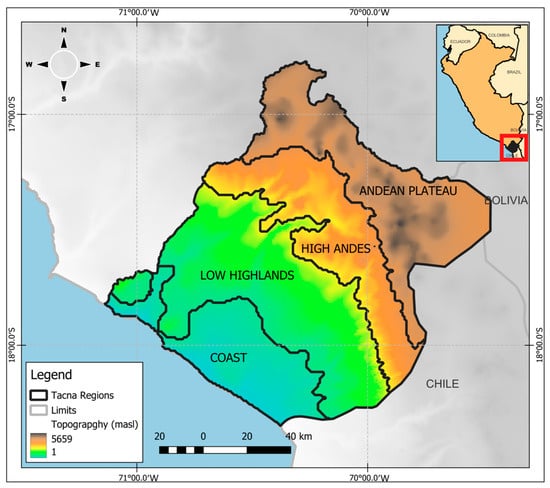

19], CMIP6 models show biases and limitations in accurately representing the annual cycle of precipitation and temperature in Peru. Specifically, these models tend to underestimate Tmax over the Andes while overestimating Tmin in the Peruvian coastal areas and generally overestimate precipitation across the Andes region. It is also worth highlighting that significant variability may exist within regions due to localized factors such as microclimates, elevation differences, and specific topographic features. These variations can result in diverse climatic conditions over relatively small spatial scales, further limiting efforts to accurately model regional climate impacts.

In this sense, there is importance of advanced bias correction techniques to improve model accuracy for temperature and precipitation variables in mountainous regions. The elimination of systematic biases in GCM simulations can significantly enhance the accuracy of statistical evaluation [

55], leading to improved model performance and more reliable climate projections. However, future studies exploring alternative statistical downscaling techniques are necessary to improve the performance in representing maximum temperature in the Coast and Andes regions.

4.2. Temperature and Precipitation Projections

The projected temperature increases for the period 2015–2100 align with various studies conducted in South America and the Andes, with the most pronounced changes occurring in the SSP5-8.5 scenario [

56,

57]. By 2050, the warming values for both Tmax and Tmin are consistent with those identified by [

58]. For maximum temperature, larger increases have been identified in the coastal regions compared to higher altitude areas. This disparity may be linked to greater cloud cover during daytime over the Andes, which helps to moderate temperature fluctuations, especially during the daytime, resulting in less variation in maximum temperatures. However, further research is needed to fully understand differences.

For Tmin, greater warming is observed at higher altitudes. In the Andean Plateau region, warming exceeds +6 °C by the end of the century. Generally, the western side of the Andes experiences greater warming compared to the eastern side [

59]. The substantial warming of minimum temperatures in the Andes may be associated with increased cloud cover during the night, which traps longwave radiation and limits nocturnal cooling, leading to higher Tmin values.

For precipitation, the high discrepancy observed in projections, particularly in the Low Highlands and Coast regions, can be explained by intensified atmospheric processes due to rising temperatures, which increase energy within the climate system and amplify variability in meteorological variables like precipitation. This variability is further influenced by complex interactions between topography, oceanic influences, and large-scale atmospheric circulations. As the climate warms, stronger atmospheric dynamics contribute to more frequent and severe extreme events, such as heavy rainfall and prolonged droughts, driven by enhanced moisture availability and shifts in circulation patterns. Additionally, model resolution limitations and uncertainties in representing convective processes and orographic effects exacerbate this discrepancy. This uncertainty presents challenges for water resource management, agriculture, and infrastructure planning, heightening exposure to floods, droughts, and inefficiencies. Addressing these challenges requires the use of high-resolution regional climate models and multi-model ensembles, which can better capture fine-scale dynamics and reduce the uncertainties associated with individual model projections.

In the coastal region, precipitation levels are so low that even large percentage changes do not result in significant increases in total rainfall. This is largely due to the aridity of the region, particularly during the JJA months, when precipitation totals are close to zero. Significant precipitation decreases have been identified only at the annual level and towards the end of the century, particularly in high-altitude regions. In the short term, the changes are minimal and consistent with [

60], which reported variations ranging from −5% to +5% by 2030, remaining within the bounds of natural variability. According to [

58], by 2050, precipitation in the mid and high-altitude areas of Tacna is expected to decrease significantly, while certain coastal areas may experience increases. In contrast, our results indicate that by 2050, precipitation in the higher-altitude regions shows a decrease, though it is not statistically significant. However, by the end of the century, annual reductions become significant, reaching up to −14.28% in the Andean Plateau. These reductions highlight a concerning trend in water availability for these regions, which are heavily reliant on consistent precipitation for sustaining ecosystems, agriculture, and water resources for downstream communities. At the seasonal level, no significant changes have been observed. This suggests that the GCMs may be projecting a redistribution of rainfall throughout the year without substantial alterations to the seasonal patterns. In other words, while the total annual precipitation may decline, the wet and dry seasons are expected to maintain relatively stable patterns, with no major changes. This implies that changes in precipitation may be more about frequency and intensity within individual events rather than a complete alteration of the seasonal cycle.

While this study provides valuable insights into future climate conditions in Tacna, certain limitations must be acknowledged. Despite improvements in CMIP6 models, biases persist in simulating temperature and precipitation in the Coast and Andes regions, particularly in terms of maximum temperature projections. These biases are likely influenced by the coarse resolution of GCMs, which fail to fully capture elevation-dependent effects and local climate variability. Additionally, the statistical downscaling method employed, though robust, introduces uncertainties related to the assumptions inherent in bias correction techniques, such as Quantile Delta Mapping. Further research could expand the scope of scenarios analyzed and incorporate alternative downscaling approaches to enhance the reliability and applicability of the findings. Moreover, using different models for various variables may disrupt coherence because each model has unique biases and assumptions, leading to discrepancies in cross-variable analyses. Consistent model selection ensures alignment and reliable relationships between projected variables.

Changes in climatic conditions are expected to have wide-ranging and complex impacts on the region. For instance, olive production in the Tacna coast would be affected, as its optimal maximum and minimum temperatures are 24.07 °C and 16.24 °C, respectively [

61]. Considering the projected climate scenarios, this crop is likely to face significant challenges including reduced yields, changes in flowering and fruiting patterns, and heightened vulnerability to pests and diseases. On the other hand, the combination of rising temperatures and declining precipitation could lead to a significant increase in evapo-transpiration, potentially causing water stress and adversely affecting vegetation. The interplay between temperature-driven evaporation and reduced precipitation could further exacerbate the vulnerability to water scarcity, highlighting the need to account for changes in evaporation intensity when assessing future humidity conditions.

Actionable strategies for the Tacna region should prioritize integrated water resource management to enhance resilience. This includes implementing water conservation measures, such as the modernization of irrigation systems to reduce losses and improve efficiency in agricultural practices. Additionally, the development of water storage infrastructure, such as reservoirs and aquifer recharge systems, will be essential to capture and store rainfall during wetter periods. Promoting the use of drought-resistant crop varieties and diversifying agricultural practices can help sustain food production in the face of declining water availability.

The implementation of water management strategies in Tacna can leverage proven frameworks like the Drought Management Plan for the Caplina–Locumba Basin in Tacna. By defining operational risk levels (Normal, Pre-alert, Alert, and Emergency), stakeholders can implement phased interventions tailored to the severity of water scarcity starting with early warning systems and progressively implementing mitigation measures such as water rationing or alternative supply solutions [

62]. This approach ensures a proactive and structured response to water scarcity, minimizing impacts on vulnerable populations and optimizing the use of available resources

Implementing these strategies in Tacna requires engaging communities for equitable resource use, strengthening local capacities to manage challenges, and securing funding through partnerships to support sustainable infrastructure projects. However, the region faces significant barriers, including economic constraints like funding large infrastructure projects and social challenges such as conflicts over equitable water distribution among stakeholders [

63]. Overcoming these barriers requires targeted funding, capacity-building programs, and strong governance frameworks to ensure effective implementation.

On the other hand, collaboration with downstream communities is critical to establish equitable water-sharing agreements, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently. Finally, fostering community engagement and raising awareness about sustainable water use, paired with the integration of climate data into regional planning, will empower stakeholders to adapt effectively to these changes.

Additionally, water demand in Tacna already far exceeds supply, driven by population growth, agricultural needs, and industrial demands. This imbalance has led to the overexploitation of underground aquifers and increasing salinization near the coast [

32], with severe consequences. In coastal areas, for example, increased salinization from marine intrusion threatens not only agricultural productivity but also the availability of freshwater for other uses. The aquifers in Tacna and the Caplina Basin are under further stress due to climate change, with altered precipitation patterns and increased variability, further threatening groundwater availability and quality [

64]. These challenges underscore the urgent need for informed decision-making and effective water management strategies.