1. Introduction

Phase change memory (PCM) has been regarded as a promising candidate for storage-class memory, embedded memory and computing-in-memory [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], owing to its outstanding performance with fast speed, good scalability and high reliability [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Unfortunately, the issue of high power consumption has long been a pain point for PCM, which limits its application in high-density integrated circuits [

13,

14]. The high power consumption of conventional PCM arises from the high-temperature melting of PCM materials during the crystalline-to-amorphous transition (RESET operation), which consumes too much energy [

13,

15]. Therefore, there has been a longstanding goal to achieve PCM through melting-free crystalline-to-crystalline phase transitions (

c-to-c PCM) [

16,

17]. The idea has been proposed in various explorations such as the layer-block sequence transition in interfacial PCM [

18], the electron beam-induced 2H-to-1T transition in MoS

2 [

19], the ultrafast laser-induced 2H-to-1T’ transition in MoTe

2 [

20,

21], the ultrafast laser-induced rhombohedral-to-cubic transition of GeTe [

22,

23,

24], and the thermally driven α-to-β and β-to-γ phase transitions in In

2Se

3 [

25,

26,

27], among others. Despite these intriguing proposals and material-level demonstrations,

c-to-c PCM devices with practical performance are still absent.

Recently, a new type of

c-to-c PCM device utilizing the reversible phase transitions between α-MnTe and β-MnTe was realized by Sutou’s group [

28]. The power consumption of the device was indeed an order of magnitude lower than that of conventional PCM devices. High-resolution TEM analyses also demonstrated that the transformation between α-MnTe and β-MnTe is a diffusionless displacement-type phase transition [

29]. At present, the endurance of the MnTe-based

c-to-c PCM device is limited to only a few hundred cycles. Therefore, optimizing the material composition, stimulation pulses and device architecture or exploring new materials with similar properties is urgently needed. The possible phase transition mechanism has been proposed in several reports by Mori et al. [

28,

29,

30]. However, the resistive switching mechanism and the atomic pathways of the phase transitions between α-MnTe and β-MnTe are still not fully understood, primarily due to the lack of dynamic pictures of the transition processes at atomic scales, which hinders the optimization and design of materials for

c-to-c PCM devices. Theoretical investigations on the experimental observations should be helpful to understand the underlying mechanisms.

In this work, we uncover the electronic origins of resistive switching, the atomic pathways of the c-to-c transitions and the effect of strain on these transitions through first-principles calculations. The resistance contrast between the two phases is attributed to differences in hole effective mass and vacancy defect formation energy. Atomic structure analyses have clarified that the previously hypothesized intermediate phase is possibly unlikely to exist. Two ‘slide-and-stand-up’ pathways of the transitions from α-MnTe to β-MnTe are identified through transition state analyses, with energy barriers of approximately 0.17 eV per formula unit (eV/f.u.) and 0.38 eV/f.u. for Path 1 and Path 2, respectively. Moreover, the energy barriers can be modulated by stress or strain. By applying experimentally feasible uniaxial strains along the c-axis, the energy barriers of the α-MnTe-to-β-MnTe transition can be reduced to 0.10 eV/f.u. and 0.26 eV/f.u. for Path 1 and Path 2, respectively. In contrast, the β-MnTe-to-α-MnTe transitions are only slightly affected by the strains. The revealed electronic and atomic mechanisms not only explain the performance of MnTe-based c-to-c PCM devices but also offer guidance for optimizing low-energy-cost PCM materials and device designs.

3. Results and Discussions

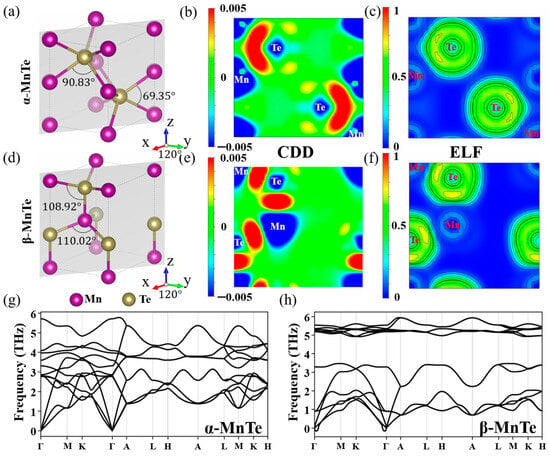

According to previous experiments, the two phases employed as the low-resistance state (LRS) and high-resistance state (HRS) in the

c-to-c PCM device are the NiAs-type hexagonal α phase and the wurtzite-type β or strained-β (β’) phase of MnTe, respectively [

28]. The atomic structures of α-MnTe and β-MnTe are shown in

Figure 1a,d. Both phases exhibit antiferromagnetic order and are therefore treated as A-type collinear antiferromagnetic materials in the following calculations [

39,

40]. The magnetic moments at the Mn sites for the two phases are shown in

Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials. The calculated lattice parameters (a = b = 4.20 Å, and c = 6.68 Å for α-MnTe and a = b = 4.54 Å, and c = 7.36 Å for β-MnTe) agree well with the experimental results [

28]. The analyses on the charge density difference (CDD) and electron localization function (ELF) in

Figure 1b,c,e,f indicate that the bonding properties of α-MnTe and β-MnTe are similar. The accumulation of electrons between Mn and Te atoms indicates a covalent bonding component, while the electron transfer from Mn to Te suggests an ionic bonding component. The calculated phonon spectra in

Figure 1g,h demonstrates that both α-MnTe and β-MnTe are stable without imaginary frequencies. Also, the optical modes of β-MnTe are more localized than those of α-MnTe, which suggests the bonds of β-MnTe are more rigid.

The experimentally measured band gaps of α-MnTe (about 1.25–1.51 eV) and β-MnTe (about 2.7 eV) are different [

41,

42,

43]. However, the resistances of the two phases are not directly determined by the band gaps, as the carrier concentrations are significantly higher than those arising from intrinsic excitation [

28]. To elucidate the origin of the resistance contrast between α-MnTe and β-MnTe, the analysis of their electronic structures is required.

Figure 2 presents the calculated band structures and density of states (DOSs) for the two phases, revealing that α-MnTe exhibits an indirect band gap of 0.76 eV, while β-MnTe features a direct band gap of 1.84 eV. These results are consistent with the experimental findings, considering the general underestimation of the band gap by DFT. In addition, we also calculated the band structure, the density of states and the total energy using larger values of U (

Figure S1 and Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials). The band structures and energy differences between α-MnTe and β-MnTe are only slightly affected. Moreover, we further performed calculations using the hybrid functional (HSE06), which better reproduces the experimental band gaps, revealing that α-MnTe exhibits an indirect band gap of 1.43 eV, while β-MnTe features a direct band gap of 2.58 eV (

Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials). The spin–orbit coupling effect is also demonstrated to have tiny influences on the band structures (see

Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials). The DOS indicates that the states near the conduction band minimum (CBM) are mainly contributed by

3d orbitals of Mn atoms, while those near the valence band maximum (VBM) are mainly composed of

p orbitals of Te atoms. According to the band structures, the band near the VBM of β-MnTe appears flatter than that of α-MnTe, suggesting a larger effective mass and potentially lower carrier mobility. To verify this, three-dimensional

E–

k diagrams near the CBM and VBM of the two phases were calculated (

Figure 3). Indeed, the 3D

E-k relations show a very flat band in β-MnTe (

Figure 3h). To provide a quantitative assessment, the effective masses of electrons at the CBM and holes at the VBM were calculated using the EMC code [

35].

Table 1 shows the calculated results. The average electron effective mass (

mn*) at CBM of α-MnTe is larger than that of β-MnTe, while the average hole effective mass at VBM (

mp* = −

mn*) of α-MnTe is smaller than that of β-MnTe. More details of the directions of the effective masses are presented in

Table S3 of the Supplementary Materials. Since both phases exhibit

p-type conductivity, the smaller hole effective mass of α-MnTe leads to higher carrier mobility compared to β-MnTe, consistent with experimental observations [

41,

44].

As for the carrier concentration, it has been reported that the

p-type conductivity of MnTe comes from the Mn vacancy (V

Mn) [

45], suggesting that the concentration of V

Mn defects governs the carrier concentrations. Then, we calculate the formation energies of V

Mn in α-MnTe and β-MnTe (see

Note S1 and Figure S4 in the Supplementary Materials for more details). The results indicate that the formation energies of V

Mn in α-MnTe (0.36–3.25 eV) are indeed lower than those in β-MnTe (1.58–4.49 eV). Based on the formation energy of V

Mn, we estimate the ratio of V

Mn concentration in β-MnTe to that in α-MnTe (

Note S1 and Figure S5 in the Supplementary Materials) [

46]. The V

Mn concentration in β-MnTe can be several orders of magnitude smaller than that in α-MnTe, suggesting that the hole concentration will be significantly reduced after the α-to-β transitions. Therefore, we propose that the concentration of V

Mn decreases after the α-to-β transition in MnTe, which in turn reduces the carrier concentrations. In brief, the origin of the resistive switching after the α-to-β transition in MnTe is attributed to the increased hole effective mass and the enhanced formation energy of V

Mn.

Understanding the atomic pathway of phase transitions between α-MnTe and β-MnTe is essential for comprehending and controlling the

c-to-c transitions. Here, the CI-NEB method is used to identify the transition states of the α-to-β phase transition, by which two possible pathways are found (

Figure 4).

Figure 4a illustrates the energy landscape of

Path 1, with an energy barrier of approximately 0.17 eV/f.u. Six atomic configurations along the transition path (labeled I to VI) are shown in

Figure 4c. These consecutive atomic snapshots reveal that the process is a displacement-type transition without long-range atomic diffusions. During the transition, the second-layer (Te) and third-layer (Mn) atoms slide along the

direction (from right to left in

Figure 4c), while the first-layer (Mn) and fourth-layer (Te) atoms move in the opposite direction (from left to right in

Figure 4c). To complete this process, two Te-Mn bonds around each atom are broken. Then, the six-coordinated configuration in α-MnTe turns into the four-coordinated tetrahedral configuration in β-MnTe. The process seems like a ‘

slide-and-stand-up’ motion of the Te-Mn bonds between the first-layer (Mn) and second-layer (Te) atoms, as well as between the third-layer (Mn) and fourth-layer (Te) atoms. As for the transition from β-MnTe to α-MnTe, it should occur in the reverse manner with an energy barrier of 0.19 eV/f.u. (

Figure 4a).

Note that the ‘

slide-and-stand-up’ pathway of

Path 1 involves the sliding of atoms along the [1

0] and [

10] directions, resembling the two-step process (α-β′-β) proposed in previous experimental studies [

29]. However, the ‘

slide-and-stand-up’ motion is directly accomplished through the sliding and rotation of chemical bonds, rather than the previously proposed two-step ‘

slide-and-expansion’ or ‘

buckling-and-puckering’ process [

28,

29]. Then, further calculations are performed to check the stability of the proposed intermediate β′ phase.

Figure S6a shows the structure of the β′ phase, adopting the lattice constant of the α phase as depicted in a previous report [

28]. It immediately turns into the β phase after structural relaxations (

Figure S6b).

Figure S6c shows the atomic forces on different atoms. The large atomic forces suggest that the structure cannot be stable. The situation is the same when the β′ phase adopts the lattice constant of the β phase (

Figure S6d). This instability is physically reasonable, as some chemical bonds in the proposed β′ phase are significantly compressed, leading to strong Coulomb repulsions that hinder the stabilization. Therefore, further experimental investigations are needed in future studies to address the issue.

We notice that the α-to-β phase transition can also be realized by the sliding motions in the opposite directions to those of

Path 1.

Path 2 is then constructed by displacing the atoms in the opposite directions to those in

Path 1. The transition states of

Path 2 are also identified by the NEB method.

Figure 4b shows the energy landscape of α-to-β transition via

Path 2, with an energy barrier of 0.38 eV/f.u. The first half of the pathway is shown in

Figure 4d (states I–III), where the second-layer (Te) and third-layer (Mn) atoms move along the [

10] direction, while the first-layer (Mn) and fourth-layer (Te) atoms move in opposite directions. For the second half of the pathway (states IV–VI in

Figure 4d), the third-layer (Te) and fourth-layer (Mn) atoms move along the [

10] direction, leading to the rotation of Te-Mn bonds between the second-layer (Te) and third-layer (Mn) atoms, as well as between the fourth-layer (Te) and fifth-layer (Mn) atoms. During the transition, up to three chemical bonds around each atom are broken (see

Figure 4d, state III). Therefore, the energy barrier is larger than that of

Path 1. Note that a β′-like transition state is observed in

Path 2, as illustrated in

Figure S6e (i.e., state III in

Figure 4d). The forces on the atoms are negligible in this structure (

Figure S6f) because the structure corresponds to the saddle point of the energy landscape (i.e., state III in

Figure 4b). No chemical bonds are compressed in such a β′-like structure. Therefore, state III and the nearby states, such as state II in

Figure 4d, may be stabilized by constraints from the surrounding matrix. Further experimental explorations are needed to clarify whether these β′-like structures are related to the previously observed β′ phase.

Next, we study the effect of stress on the

c-to-c transition in MnTe because considerable stresses may exist due to device constraints or thermal expansion effects. For instance, it has been reported that the c-axis lattice constant of the β′ phase is very close to that of α phase, indicating that the β′-MnTe is a strained phase under compression stress [

28]. Similarly, another report shows that the c-axis lattice constant of the α phase near the α-MnTe/β-MnTe interface after the β-to-α transition is close to that of β-MnTe, suggesting it is a strained phase under tensile stress [

47]. Therefore, the effects of stress and strain on the phase transition warrant further investigation.

According to experimental reports [

28,

47], two strain or stress conditions are considered (

Figure 5a): (1) the α-strained condition, where the c-axis lattice constant of α-MnTe is strained to match that of β-MnTe during the transition, and (2) the β-strained condition, where the c-axis lattice constant of β-MnTe is strained to match that of α-MnTe during the transition. Note that under both strained conditions, the lattice constants of α-MnTe and β-MnTe along the a- and b-axes are slightly relaxed due to Poisson’s effect (see

Figure 5a). CI-NEB calculations are then performed for the transitions under the two strained conditions: from α-strained α-MnTe to strain-free β-MnTe and from strain-free α-MnTe to β-strained β-MnTe (see

Figures S7 and S8). The energy barriers of the phase transitions are altered, while the transition pathways remain unchanged (

Figure 5b–e). For

Path 1 under the α-strained condition (

Figure 5b), the energy barrier for the α-to-β transition decreases significantly to 0.10 eV/f.u., while the barrier for the β-to-α transition increases slightly to 0.22 eV/f.u. (

Figure 5c). In contrast, under the β-strained condition, the energy barrier for the α-to-β transition via

Path 1 increases to 0.23 eV/f.u. (

Figure 5b), while the barrier for β-to-α transition decreases slightly to 0.18 eV/f.u. (

Figure 5c). For

Path 2, the α-strained condition not only significantly reduces the energy barrier for α-to-β transitions to 0.26 eV/f.u. (

Figure 5d) but also slightly reduces the barrier for β-to-α transition to 0.37 eV/f.u (

Figure 5e). The β-strained condition in turn enhances both of the barriers for α-to-β and β-to-α transitions. According to ref. [

28], the temperature for α-to-β transition is higher than that for β-to-α transition. Therefore, we suggest introducing tensile strains along the c-axis in the device to further reduce the RESET voltage. The lattice of β-MnTe under the z-direction compression condition is relaxed along the x-y directions. If the lattice is not relaxed along the x-y directions, the total energy of the β-MnTe will be 0.18 eV/f.u. larger than the energy of α-MnTe. The energy difference between α-MnTe and β-MnTe is smaller than that in a recent experiment [

30]. The reason may be that the calculations are performed at 0K. Further investigations at finite temperatures are needed to clarify the issue.