1. Introduction

Dengue, Zika, and chikungunya are arboviral diseases transmitted by the dengue virus (DENV), which has four serotypes (DENV-1 to DENV-4), the Zika virus (ZIKV), both belonging to the

Flavivirus genus (Flaviviridae family), and the chikungunya virus (CHIKV), classified under the

Alphavirus genus (Togaviridae family) [

1].

As of 19 December 2024, the Americas reported 12.78 million suspected dengue cases, with 6.78 million confirmed and 7822 fatalities (Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) [

2]. The PAHO data also report 225,094 confirmed cases of chikungunya, with 211 fatalities, as well as 2048 cases of Zika with one fatality during the same period [

3]. Brazil accounted for 53% of all arbovirus cases, with 6.89 million infections, including 6.62 million dengue cases (5959 deaths), 6081 Zika cases (no deaths), and 266,241 chikungunya cases (210 deaths) [

2].

Another disease of significant epidemiological importance in the Americas is malaria, which Brazil, Venezuela, and Bolivia account for 73.0% of the cases [

4]. In Brazil, malaria is primarily caused by the etiologic agents

Plasmodium vivax and

P. falciparum (Plasmodiidae), which are responsible for 82.7% and 13.3% of the 128,214 cases reported in the country in 2024, respectively [

5].

The high incidence of malaria in Brazil is influenced by environmental and socioeconomic conditions that favor the proliferation of the mosquito

Anopheles darlingi Root, 1926 (Diptera: Culicidae), the primary vector of the disease, and increase the population exposure to this transmitter [

6]. Similarly, dengue, Zika, and chikungunya present an alarming scenario fueled by the presence of

Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 1762 (Diptera: Culicidae), in urban environments [

1]. These factors result in a heterogeneous and complex spatial distribution, with varying scenarios and risks of occurrence for both malaria and these arboviruses [

5].

Another critical factor influencing the proliferation of

An. darlingi and

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes is their increasing resistance to synthetic insecticides, performed by the action of detoxifying enzymes that play a crucial role in the survival and maintenance of these species [

6]. Mosquitoes possess enzymatic systems such as esterases, oxidases, mono-oxygenases, and others like glutathione S-transferases, which help break down and neutralize the harmful effects of insecticides such as organophosphates, carbamates, and pyrethroids [

6].

These enzymes provide a defense mechanism that allows these species to withstand exposure to synthetic chemicals [

7]. Furthermore, oxidative stress, induced by the accumulation of reactive oxygen nitrogen species (RONS) during insecticide exposure, whether natural or synthetic, triggers the activation of these detoxifying enzymes as part of the organism’s defense response [

8]. This adaptive mechanism enables mosquitoes to mitigate the damaging effects of oxidative stress, promoting their survival [

9].

The enhanced detoxifying enzyme activity and oxidative stress tolerance in resistant mosquitoes enable their survival under high insecticide pressure, sustaining populations and disease transmission [

10]. Therefore, the resistance reduces the effectiveness of chemical control strategies, allowing vector populations to persist and spread in both rural and urban environments [

11].

Currently, detoxifying enzymes involved in mosquito defense against insecticides and those associated with neurological processes, including acetylcholinesterase, have been extensively studied [

8]. Furthermore, oxidative stress caused by RONS during insecticide exposure has garnered scientific interest due to its role in vector survival mechanisms, being investigated not only to understand resistance processes but also to develop innovative control strategies that can overcome the limitations of current approaches [

7].

Another problem in applying synthetic insecticides in breeding sites poses considerable environmental risks due to their high toxicity to non-target species, including beneficial organisms in aquatic ecosystems [

12]. Indeed, recent research has shown that α-cypermethrin (LC

50 between 0.22 and 0.29 μg/mL) [

13] and temephos (LC

50 between 4.85 and 5.82 μg/mL) [

14] exhibit significantly higher toxicity against non-target species like

Toxorhynchites sp. Theobald, 1901 (Diptera: Culicidae),

Anisops sp. Spinola, 1837 (Hemiptera: Notonectidae),

Gambusia sp. Poey, 1854 (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae), and

Diplonychus sp. Leach, 1815 (Hemiptera: Belostomatidae).

Considering the diversity and ecological importance of these species in aquatic environments, as they play essential roles as predators, decomposers, and prey for other animals [

15], it is imperative to adopt more sustainable and targeted mosquito control measures to mitigate or reduce the toxic effects on non-target organisms and the environment [

16].

Due to growing concerns about environmental safety, insecticides based on natural bioactive compounds, particularly from plants, have become an effective alternative for controlling a wide range of insects with low toxicity to non-target organisms [

17], providing a more sustainable solution for managing pests and disease vectors [

18].

Plant-derived compounds used as insecticides are highly toxic to target insects specific to these organisms while being harmless to beneficial species and having a lower environmental impact [

19]. Recent studies have shown that natural compounds extracted from plants exhibit biological activity, acting selectively on target organisms while preserving beneficial and essential species in aquatic ecosystems [

20,

21].

Insecticide compounds, such as amides, in arthropods primarily cause symptoms such as hyperactivity, hyper-excitation, rapid knockdown, and immobilization [

22]. Several amides [

20,

21] can directly or indirectly affect a wide range of targets, including insect proteins, receptors, ion channels, neurotransmitter systems, and enzymes involved in signal transduction pathways, which act as agonists or antagonists, disrupting normal neural functions, leading to paralysis, convulsions, and eventual death.

Additionally, according to Rattan [

23] and Ganesan et al. [

24], some amides can also induce the overproduction of RONS, causing oxidative stress and cellular damage, as well as alterations in the activity of defense enzymes, including catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), thiols, esterases, and mixed-function oxidases (MFOs). Common targets of plant-derived compounds include acetylcholinesterase (AChE).

Several studies have reported the biological activity of amides derived from various plants, including those of the genus

Piper (Piperaceae) against Culicidae. For example, pellitorine (from 0.4 to 5 μg/mL) [

25,

26,

27], lansiumamide B (at 0.45 μg/mL) [

28], piperine and piperanine (at 0.27 and 0.37 μg/mL) [

29], piplartine (at 50 μg/mL) [

30], n-isobutil-2

E,6

Z,8

E-decatrienamide, n-isobutil-2

E-decenamide, and n-isobutil-decanamide (from 4.24 to 50 μg/mL) [

31], guineensine, retrofractamide A, and pipercide (from 1.5 to 3.2 μg/mL) [

26], wuchuyuamide I (at 26.16 μg/mL) [

32], and other amides [

24] demonstrated the potential to interfere with critical physiological processes in mosquito larvae, particularly in

An. albimanus Wiedemann, 1821,

An. gambiae Giles, 1902,

An. quadrimaculatus Say, 1824,

An. sinensis Wiedemann, 1828,

An. subpictus Grassi, 1899,

An. stephensi Liston, 1901,

Ae. aegypti,

Ae. albopictus (Skuse, 1894),

Ae. togoi Theobald, 1907,

Ae. subpictus Grassi, 1899,

Culex quinquefasciatus Say, 1823,

Cx. pipiens pallens Coquillett, 1898, and

Cx. tritaeniorhynchus Giles, 1901, contributing to the population reduction in these vectors without compromising local biodiversity.

The adoption of amides for mosquito control not only reduces the risks associated with synthetic chemicals but also promotes a more stable ecological balance by preserving natural predators and other species that play crucial roles in aquatic environments [

33,

34].

Regarding genus Piperaceae plants,

Piper purusanum Yunck. is a shrub characterized by alternate ovoid leaves measuring 8.7 cm in length, with an oblique base and a petiole of about 0.3 cm, with erect inflorescence around 1.5 cm long, along with a sheath, midrib, secondary veins, stipules, and a stem and branches covered in spikes. It has a restricted distribution in the State of Amazonas, Brazil, as reported by Guimarães et al. [

35]. The first report of the biological activities of the essential oil and its major compounds from this plant against

Ae. aegypti and

An. darlingi larvae, as well as their low toxicity to non-target aquatic animals, is described in detail in our study [

13].

In this context, we hypothesize that piplartine could be an effective alternative for larval control, particularly against malaria and dengue vectors, with minimal toxic effects on non-target organisms, making it a safe and sustainable option for vector management. Thus, this study aimed to isolate and identify the amide piplartine from a crude leaf extract of P. purusanum using bioassay-guided methods. We investigated its larvicidal activity and mechanism of action against Ae. aegypti and An. darlingi to determine its effectiveness in vector control. Additionally, we evaluated its impact on non-target organisms to assess its environmental safety.

3. Discussion

The Piperaceae family is a diverse group of plants consisting of five genera and over 3000 species, characterized by their versatile stem structures and pinnate leaves [

37]. These species are predominantly distributed across tropical and subtropical regions [

38]. Among them, the genus

Piper, comprising more than 1000 species, is particularly notable for its abundance of secondary metabolites, including amides and alkaloids, which exhibit a wide range of biological activities with a pronounced effect on arthropods [

39].

Among amides, piplartine, also known as piperlongumine, is a bioactive compound that was first isolated in 1967 from the petroleum ether extract of the dried stem bark and roots of

P. longum Linnaeus, yielding 2.5 g obtained using classical techniques for isolation, purification, and characterization including column chromatography, ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry, which collectively confirmed the compound structure and identity [

40]. Later, the compound was also described in

P. tuberculatum Jacq. [41] and P. aborescens Roxb. [

42].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the presence of piplartine in the leaves of

P. purusanum, in which the fragmentation patterns and chemical data were consistent with those previously reported for piplartine isolated from the roots, fruits, and leaves and seed of

P. aborescens Roxb.,

P. cernuum Vell,

P. longum L., and

P. tuberculatum Jacq. [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

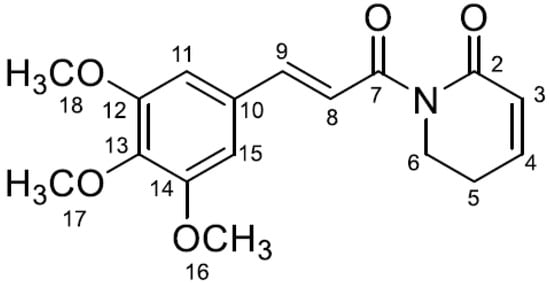

Regarding its chemical characteristics, piplartine consists of two carbonyl groups. The first is directly attached to carbon number 7, which is connected to the pyridine ring, while the second is located on carbon number 2 of the pyridine ring. Additionally, there are three methoxy groups attached to carbons 12, 13, and 14 (

Figure 1), interacting significantly for the biological activity of the molecule [

46].

The methoxy groups, being electron-donating, increase the electronic density in the aromatic ring, influencing its polarity and stability, which promotes solubility and interaction with biomolecules [

38]. On the other hand, the carbonyl groups, being electrophilic, participate in important interactions with proteins and enzymes, such as hydrogen bonding, and contribute to the molecule reactivity and affinity with biological targets [

44].

This interaction between the methoxy and carbonyl groups creates a balance that enhances solubility, permeability, and biological activity, which is essential for the insecticidal properties, as described with

Ae. aegypti larvae; with a decrease in L3, the adult development time from 3 days to 1 day was observed at concentrations of 1 and 10 μg/mL of piplartine, respectively, compared to the negative control, which ranged from 4 to 5 days [

31]. Additionally, larvicidal activity was noted, with an LC

50 of 155.5 μg/mL [

30]. This larvicidal activity was also reported against

Ae. aegypti and

An. darlingi larvae, described in

Table 2.

According to Maleck et al. [

30], several significant changes were observed in the digestive tract, indicating cellular stress followed by apoptosis on

Ae. aegypti larvae. These changes include intense cytoplasmic vacuolization, shortened and sparse microvilli, the presence of myelin, and disorganized cellular structures. Additionally, some nuclei in the midgut cell exhibited DNA extraction, further highlighting the extent of cellular damage. In fact, the observation of myelin in mosquito larvae cells could indicate cellular stress, as this structure is often associated with cell damage and breakdown in other biological contexts [

47].

The cellular damage described by Maleck et al. [

30] suggests that piplartine induces oxidative stress in

Ae. aegypti larvae, even though the authors did not perform biochemical or enzymatic assays to investigate this effect directly. In contrast, our findings, as shown in

Figure 3a,b, provide clear evidence that piplartine at a concentration of 25 μg/mL significantly promotes the overproduction of RONS in both

Ae. aegypti and

An. darlingi larvae, therefore elucidatingClick or tap here to enter text. a larvicidal mechanism of action. Indeed, a recent review conducted by da Azevedo Da Silva et al. [

43] confirmed the potential of this compound in induced RONS and apoptosis cells.

Exposure to bioactive compounds, such as piplartine, causes significant cellular damage in mosquito larvae, disrupting vital functions and leading to death [

48]. The main alterations observed include disorganization of the intestinal epithelium, characterized by intense cytoplasmic vacuolization, reduction or destruction of microvilli, and the general disruption of epithelial cell structures, which are often attributed to the induction of oxidative stress, evidenced by the excessive production RONS, which promote lipid peroxidation and compromise the integrity of cellular membranes [

49]. Furthermore, nuclear alterations, such as the extraction of genetic material, suggest the activation of programmed cell death processes (apoptosis) or necrosis [

47].

The overproduction of RONS contributes to an increased generation of free radicals, which can cause significant damage to critical biomolecules such as lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids [

48]. This process disrupts the organism antioxidant defense system, creating an imbalance that exacerbates oxidative stress [

50]. Due to their reactivity, these species can interact with a wide range of biomolecules, amplifying the complexity and extent of oxidative damage within the organism [

51]. These findings highlight the potential of bioactive compounds such as piplartine as larvicidal agents for vector control, acting through multiple cellular mechanisms [

52].

The correlation between larvicidal or insecticidal activity and the production of RONS has been clearly demonstrated in various arthropod species, including

Ae. aegypti,

An. darlingi,

Cx. quinquefasciatus Say, 1823,

An. stephensi Liston, 1901 (Culicidae),

Drosophila melanogaster Meigen, 1830 (Drosophilidae),

Ephestia kuehniella Zeller, 1879 (Pyralidae), and others. This effect was observed following exposure to essential oils and compounds such as β-caryophyllene, fenchone, 4-vinylcyclohexene 1,2-monoepoxide, and 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide, which are derived from plants like

P. tuberculatum Jacq.,

P. purusanum C.DC.,

P. alatipetiolatum Yunck. (Piperaceae),

Tetradenia riparia (Hochstetter) Codd (Lamiaceae), and

Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. (Poaceae), as well as synthetic insecticides such as α-cypermethrin, temephos, and imidacloprid, which have also been linked to similar effects [

13,

48,

50,

51,

52,

53].

The RONS in mosquito larvae, induced by amides such as piplartine, triggers significant oxidative stress that causes critical alterations in the organism antioxidant and metabolic systems [

54]. This increase in RONS acts as a signal for the activation of antioxidant defense mechanisms, leading to an elevation in the activity of protective enzymes such as catalase, GST, MFO, and esterases (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). However, AChE activity often decreases, suggesting a direct impact of the amides on essential neurological and metabolic processes [

53] (

Figure 4c,d).

CAT plays a pivotal role in neutralizing hydrogen peroxide, converting it into water and oxygen [

7]. Elevated CAT activity indicates the organism effort to mitigate the deleterious effects of oxidative stress [

49]. Complementarily, GST acts by conjugating reduced glutathione to reactive species, facilitating the detoxification of xenobiotic compounds and lipid peroxidation products [

47]. MFOs are essential for the oxidative metabolism of xenobiotics, while esterases contribute to the degradation of esters and other toxic compounds [

55].

On the other hand, the decline in AChE activity can be attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, the accumulation of RONS and associated oxidative damage may compromise the structure and functionality of the enzyme, reducing its efficiency [

56]. Secondly, amides such as piplartine may directly inhibit AChE by interacting with its active sites, an effect observed in several studies on insecticidal compounds [

57]. This reduction in AChE activity has significant implications, as the enzyme is fundamental for regulating neurotransmission [

58]. Its inhibition can lead to acetylcholine accumulation in synapses, resulting in neuromuscular dysfunction, paralysis, and eventually larval death [

53].

The decline in AChE activity, in contrast to the increased activity of other defense enzymes, highlights the complexity of the organism response to induced oxidative stress [

14]. While antioxidant and metabolizing enzymes attempt to mitigate cellular damage, AChE inhibition compromises neurological function, intensifying the toxic effects of amides [

54]. This imbalance between defense mechanisms and oxidative damage represents one of the primary larvicidal mechanisms of amides, emphasizing their effectiveness in vector control [

59,

60,

61].

Regarding the comparative toxicity assessment of piplartine and α-cypermethrin for non-target aquatic insects, the results obtained in this study provide robust and conclusive evidence regarding the toxicological differences between piplartine and α-cypermethrin, two compounds with potential for vector control but with markedly distinct toxicity profiles. Piplartine, even at a high concentration of 264.4 μg/mL, showed no observable toxicity, resulting in 100% survival for Notonectidae, Gerridae, Corixidae, Nepidae, Mesoveliidae, Belostomatidae, Chironomidae, Neocoridae, Caenidae, and Hydrophilidae over a 30-day period. DMSO, used as a solvent control, also demonstrated equivalent safety, causing no negative impacts on the tested species. In contrast, α-cypermethrin, applied at a substantially lower concentration (0.025 μg/mL), induced acute toxicity in all species, with a survival rate of only 9.1% after three days of exposure.

In fact, for example, α-cypermethrin and several synthetic larvicides, including lambda-cyhalothrin, thiamethoxam, and temephos, have been shown to be highly toxic to non-target species such as

Cyprinus sp. (Cyprinidae),

Diplonychus sp. (Heteroptera),

Toxorhynchites sp. (Culicidae),

Anisops sp. (Hemiptera), and

Gambusia sp. (Poeciliidae), with LC

50 values ranging from 0.22 to 5.82 μg/mL [

9,

13,

14]. In a recent study, the acute and rapid toxicity of α-cypermethrin at a concentration of 0.39 μg/mL was observed on

T. haemorrhoidalis,

A. bouvieri, and

D. indicus, resulting in the complete mortality (100% death rate) of these animals [

50].

These results highlight the importance of selecting fewer toxic alternatives for vector control, considering the environmental impacts that insecticides can have on non-target organisms, especially those inhabiting aquatic environments [

13]. While α-cypermethrin is widely used for its effectiveness, its devastating effects on non-target species, as evidenced by Cox regression and Kaplan–Meier analysis, emphasize the need for more sustainable strategies [

62]. The Cox regression revealed that the mortality associated with α-cypermethrin was 54.6 times higher than that observed with piplartine or DMSO, indicating pronounced lethality that could compromise aquatic biodiversity [

63].

On the other hand, piplartine demonstrated a favorable safety profile, likely due to its selective action on specific physiological mechanisms in mosquitoes without affecting other groups of aquatic insects [

64]. The absence of mortality suggests a wide safety margin and positive ecological compatibility of piplartine with non-target aquatic organisms [

65]. This aspect is particularly relevant when considering these species’ diversity and ecological importance in aquatic environments, as they play essential roles in maintaining aquatic ecosystems, such as predators, decomposers, and prey for other animals [

15].

Moreover, the covariate analysis revealed that the insect order did not influence the mortality outcomes, reinforcing the consistency of the results and suggesting that the observed response was solely due to the treatments rather than variability among species [

66]. The statistical robustness of the results, supported by highly significant

p-values, further strengthens the confidence in the conclusions that piplartine poses a low risk to non-target aquatic organisms in contrast to α-cypermethrin [

67].

It is important to highlight that many of the non-target aquatic insects tested in this study inhabit aquatic environments that often face varying degrees of pollution, which may have influenced their ability to cope with environmental stressors [

12,

55]. In contaminated aquatic ecosystems, many of these organisms have developed defense systems adapted to detoxifying xenobiotics, such as antioxidant enzymes and phase I and II metabolizing enzymes [

12]. Such adaptations may have contributed to the resistance observed in several of the tested species, as these insects may be more efficient in neutralizing the toxic effects of compounds present in the environment, including pesticides [

68]. This factor may partially explain the absence of mortality observed in the groups treated with piplartine and DMSO, as the ability to metabolize and excrete toxic substances may have acted as a protective mechanism against the compound effects [

69].

In contrast, α-cypermethrin, being a broad-spectrum insecticide with a less selective mode of action, likely interferes directly with critical physiological pathways, causing irreparable damage to non-adapted aquatic insects [

12]. The observed acute toxicity, even at low concentrations, can be attributed to the inability of these species to properly metabolize the compound, leading to the accumulation of free radicals and irreversible cellular damage [

70].

The presented results have crucial implications for environmental risk assessment and the development of safer alternatives for mosquito control, such as Culicidae [

71]. Piplartine, with its much lower toxicity to non-target aquatic insects, positions itself as a promising alternative in vector control programs while also preserving aquatic biodiversity, and its use could significantly reduce the adverse ecological impacts caused by traditional insecticides, such as α-cypermethrin, which pose high risks to non-target organisms [

68].