1. Introduction

Natural products have been used since ancient times to treat human diseases, and the popular knowledge in traditional medicine provides information for the discovery of novel medicines and therapies from products of animal, plant, and mineral origin [

1]. Honey is a food produced by bees, especially by

Apis mellifera, that is extensively used due to its several biological activities [

2]. Therefore, this food was used to treat wounds and tissue lesions and was a common medical practice in hospitals across Europe until the 1970s, due to its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities, stimulation of tissue repair, deodorant action, and injury tissue debris [

3]. Currently, modern medicine has rediscovered the honey therapeutic properties in infection treatments in hospitalized patients, as an adjuvant and alternative therapy against resistant microorganisms [

4,

5].

The growing interest in an atypical honey variety, commonly referred to as honeydew honey, has stemmed from its distinct nutritional, sensory, and potential therapeutic attributes [

6,

7]. Honeydew honey, derived by bees (

Apis mellifera) from secretions of living plant parts or excretions of plant-sucking insects, stands in contrast to the more familiar blossom honey produced from flower nectar [

8]. Despite its higher richness in phytochemical components and the consumption of honeydew honey, the literature is still limited regarding its biological properties when compared to floral honeys. Additionally, the chemical characterization of honeydew honey remains challenging due to its complex composition and the variability in its botanical and entomological origins [

9,

10].

The microorganisms’ resistance to antibiotics has increased and is considered a public health problem [

11]. The pharmaceutical industry invests in the research and development of novel medicines with an alternative mechanism of action; however, microorganisms increasingly possess an arsenal to overcome all obstacles to medicine. Moreover, the search for alternative therapies, and sources for the bioprospection of novel medicines, must be stimulated [

12]. Several studies have shown floral honey as a promising antimicrobial in different microorganisms causing human diseases, such as protozoa [

13,

14], fungi [

15], and bacteria [

16].

Recent studies have investigated honeydew honey as a functional food with potential health benefits [

7,

17], although there remains a lack of detailed information regarding its specific indications. Research indicates that honeydew honey possesses antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities, attributed to bioactive compounds such as phenolics, proteins, and amino acids [

6,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This honey has a higher concentration of phenolic compounds compared to flower honeys, resulting in potent antioxidant activity [

22,

23]. Furthermore, its anti-inflammatory property has been highlighted, demonstrating efficacy in the treatment of ulcers and wounds [

24].

Regarding antimicrobial activity, honeydew honey shows superior performance, particularly against

Staphylococcus aureus and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, due to its unique composition and higher acidity [

25,

26,

27]. However, few studies have demonstrated its antimicrobial activity against bacteria responsible for human infections [

6,

28], and none against periodontal pathogens. A search in the PubMed© database was conducted in March 2025, with no date restrictions, revealing only 64 indexed articles for the term ‘Antimicrobial honeydew’, while the term ‘Antimicrobial honey’ (using the Boolean operator ‘not’ to exclude ‘honeydew’) resulted in 2810 indexed articles. Despite the various biological properties reported for the honeydew variety, studies on its antimicrobial activity remain limited when compared to floral honey. Therefore, further research into this variety is essential, particularly considering the current global issue of multi-resistant infections.

The microorganisms present in the oral microbiota can cause different types of diseases. Periodontal disease is one of the most prevalent pathologies in the oral cavity and similar to dental caries, both are biofilm-dependent [

29,

30]. The consequences of periodontal disease include tooth loss, inflammation, halitosis, and difficulty chewing. The supragingival and subgingival biofilm formation is a crucial factor to establish and subsequently facilitate the progress of periodontal disease [

31]. The microbial colonization by the periodontopathogens and the inflammatory process are responsible for the clinical damage caused by periodontal disease [

32].

The orientation of prevention against periodontal disease includes a toothbrush, dental floss, mouthwash, and frequent visits to the dentist [

33]. Nonetheless, until now, there has been no report of using functional foods as an alternative therapy to prevent or treat periodontal disease. Despite honey’s antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties having already been related in the scientific literature, the research of these biological activities regarding periodontal disease is incipient primarily about the antimicrobial activities against oral biofilms, especially related to honeydew honey produced organically. Therefore, we evaluated in vitro and in vivo the effect of Brazilian organic honeydew (OHD) on microbial components and bone resorption in the periodontal disease model.

4. Discussion

The antibacterial properties of honey are well documented in the scientific literature [

41]. Numerous studies have demonstrated its activity against significant systemic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [

42],

Escherichia coli,

Proteus mirabilis,

Shigella flexneri, and

Staphylococcus epidermidis [

43]. However, there is a paucity of studies examining the antibacterial activity of honey against oral microorganisms, particularly periodontal pathogens [

16].

In previous research, we conducted a bioassay-guided screening of eight samples of Brazilian organic honey from the Atlantic Forest against cariogenic oral microorganisms [

16] and also against the

P. gingivalis W83 strain (unpublished data). All tested samples, including both honey (floral honey and honeydew honey) and its extracts, exhibited antibacterial activity against

P. gingivalis. The organic honeydew honey from

Mimosa scabrella (OHD), sample 7, showed the best results and was selected for further biological assays. OHD exhibited MIC and MBC values of 4% and 6% (

w/

v), respectively, against

P. gingivalis. These results suggest that organic honey may be a promising functional food against periodontal pathogens such as

P. gingivalis, warranting further research into its components and their role in periodontal disease.

Previous studies evaluated the antimicrobial activity of Manuka honey against various

P. gingivalis strains, including ATCC 33277, M5-1-2, MaRL, and J361-1, showing a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2% for all strains [

44]. Another study tested Manuka and clover honey against

P. gingivalis ATCC 33277, finding MIC values of 12.5% for both types of honey [

45]. Manuka honey from New Zealand is highly valued for its antimicrobial activity, which is not linked to peroxides and is often used in medical treatments due to its medicinal properties [

46,

47]. In contrast, OHD’s antimicrobial activity is primarily attributed to the peroxides produced by its enzymatic complex, as well as other components like phenolic compounds [

16].

In this study, Brazilian organic honey demonstrated promising MIC values against

P. gingivalis, comparable to those found for Manuka honey. Other studies have evaluated Egyptian honey [

48], Manuka honey, and a multifloral honey against oral microorganisms, including

P. gingivalis, with positive results. However, the use of the agar diffusion method in these studies complicated comparisons, as this method is not recommended for honey due to its high viscosity. This can lead to issues such as incorrect well volumes and inadequate diffusion of active components, resulting in unreliable data [

49,

50].

The antimicrobial activity of honey is well-established, but there is no consensus among scientists on the optimal methodology for evaluating it [

50]. Antimicrobial activity is just one of the initial steps in bioassay-guided studies aimed at discovering new substances with potential antimicrobial properties [

51]. However, with the rise in antimicrobial resistance and the severity of biofilm-associated diseases, assessing antibiofilm activity is essential for new antimicrobial therapy candidates [

52]. Microorganisms in biofilm form are organized in terms of architecture and integrity, making them up to 1000 times more resistant [

53].

Biofilms are dense microbial communities that grow on surfaces and are encased in high molecular weight polymers they secrete. As bacteria form biofilms, they adapt to environmental changes, altering their genetic expression patterns and becoming highly resistant to antimicrobials [

54]. Therefore, assessing the antibiofilm activity of antimicrobial honey is crucial for characterizing it as a protective agent against biofilm-related diseases, such as periodontal disease [

55].

Despite its widespread use as a medicinal agent, research on honey’s activity against oral biofilms remains limited. Studies assessing the antimicrobial activity of honey against mature oral biofilms are scarce. One study demonstrated that both Manuka honey and a German multifloral honey inhibited the formation of mature

P. gingivalis biofilms at a concentration of 10%, reducing bacterial viability within the biofilm for 42 h, but did not completely prevent biofilm formation or eliminate the biofilm [

44]. Another study evaluated the effect of supermarket honey from Saudi Arabia on

S. mutans biofilm formation, finding that 25% and 50% concentrations significantly reduced biofilm growth on polystyrene plates [

56]. However, no reports were found on antimicrobial activity against multispecies or subgingival biofilms. Therefore, this research provides novel data that fill a gap in the scientific literature.

This is the first study to investigate the antibiofilm activity of this functional food, providing essential data on its efficacy against a complex multispecies subgingival biofilm composed of 34 species. The use of a multispecies biofilm model, implemented with a Calgary device, adds to the study’s significance, as it closely mimics the in vivo oral environment and presents a greater challenge for antimicrobial testing. Moreover, this research contributes to filling a gap in the literature regarding honeydew honey. We previously employed this model to assess the antibiofilm potential of various bee products, including red propolis, reinforcing its reliability for evaluating natural antimicrobial agents [

36].

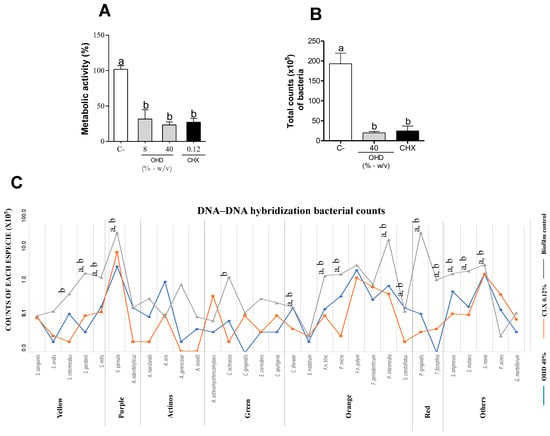

In our assays, the concentration used to treat the biofilm was based on the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for P. gingivalis (2× and 10× MIC). Treatments were administered twice daily for 1 min over a period of four days, with a six-hour interval between applications. Treatment with OHD significantly reduced the overall metabolic activity of the biofilm and showed no statistical difference compared to the positive control (CLX) (p > 0.05). Moreover, its strong antimicrobial activity and a lower concentration (2× MIC at 8%) reduced biofilm viability without differing from the gold standard (p > 0.05).

Our research group previously studied the antioxidant activity of eight organic honey samples, including OHD, and identified key chemical compounds in the crude honey extracts. The total phenolic content (mg GAE/g) values found in the honey extracts were 73.15 (OH-1), 59.79 (OH-2), 49.79 (OH-3), 52.20 (OH-4), 117.68 (OH-5), 84.08 (OH-6), 83.19 (OHD), and 53.03 (OH-8). Four phenolic compounds were identified: ferulic acid, caffeic acid, rutin, and hesperidin [

57]. Additionally, significant amounts of ascorbic acid were found, ranging from 2.75 to 6.22 mg/100 g in OH-3, OH-5, and OHD. Previous studies have demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity for the compounds identified in these organic honey samples [

58,

59].

Several compounds identified in the OHD sample are known for their anti-inflammatory activity, including apigenin [

60], quercetin [

61], and hesperidin [

62]. Interest in flavonoids has increased in recent years due to their diverse biological activities beyond anti-inflammatory effects, such as antioxidant properties, antidiabetic property, and antimicrobial activity [

63].

Two compounds found in the OHD sample belong to the phenolic class known as lignans: anhydrosecoisolariciresinol and matairesinol. These compounds are classified as phytoestrogens and are commonly found in fruits and vegetables. They have also been identified as chemical markers in Brazilian organic propolis type 1. Through intestinal microbiota action, these lignans can be metabolized into enterolactone and enterodiol, and their biological activity is linked to this metabolism [

64]. Lignans are reported to have therapeutic potential, including antioxidant, anticancer, gene expression modulation, antidiabetic, estrogenic, antiestrogenic, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [

65].

Fruits, vegetables, tea, and wine are the main dietary sources of flavonoids for humans. Since bees collect nectar from local flora, the chemical composition of floral and multifloral honey reflects the plant species involved. Consequently, other studies have also identified flavonoids in floral and multifloral honey samples [

66].

OHD is a honeydew honey obtained from the Bracatinga tree (

Mimosa scabrella), differing from floral honey in its origin. While floral honey is produced from flower nectar, honeydew honey is derived from plant secretions or the excretions of plant-sucking insects, as defined by the European Commission Directive (2002) [

8]. Compared to floral honey, honeydew honey generally has higher pH, electrical conductivity, liquid absorbance, ash content, and levels of disaccharides, trisaccharides, phenolic compounds, and proteins, which enhance its biological activities. Additionally, honeydew honey is darker in color and has unique sensory characteristics [

17,

67]. Honeydew honey is known to have a higher concentration of bioactive compounds, such as phenolics, proteins, and amino acids, compared to floral honey. This amplifies its antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, and for this reason, it has attracted the attention of researchers and consumers alike [

66,

67].

Honeydew honey exhibits strong antimicrobial activity, particularly against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Heterotrigona itama honey effectively inhibits

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus, with bactericidal effects confirmed by endotoxin release assays and scanning electron microscopy, which revealed cellular destruction [

28]. Czech

honeydew honey demonstrated potent antibacterial activity, with a lower minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against Gram-positive bacteria than medicinal honeys and comparable efficacy against Gram-negative bacteria [

68]. Certified samples of honeydew also exhibited activity against

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Streptococcus spp.,

Bacillus cereus, and

Yersinia enterocolitica, in addition to serving as a reservoir of bacteria that produce antimicrobial and probiotic metabolites. Its inhibitory effect on urease suggests potential applications in the treatment of specific bacterial infections [

6,

69].

These findings reinforce honeydew honey as a promising natural antimicrobial agent and an alternative in the fight against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Despite the promising antimicrobial activity of honeydew against pathogenic bacteria, its effects on oral microorganisms, particularly periodontopathogens, have not yet been reported. This study provides data that support the sustainable exploration of this functional food, both in the search for bioactive molecules with antimicrobial potential and as a dietary alternative to sugar to help prevent biofilm-associated oral diseases, such as periodontal disease.

A study on the chemical composition of honey and its extracts found a biphasic structure necessary for hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) production and antibacterial activity [

70]. The same research group highlighted that the arrangement of active macromolecules in honey, organized into stable colloidal structures, is crucial for understanding the biological activities influenced by this structural complexity.

In a previous study, we demonstrated the significant anti-inflammatory activity of various organic honeys from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, which reduced NF-κB activation and TNF-α cytokine levels in vitro. Additionally, OHD reduced NF-κB activation by 87% in an in vitro assay using RAW 264.7 murine macrophages and decreased neutrophil migration by 59% in an in vivo mouse model of carrageenan-induced peritonitis [

71]. Since periodontal disease has both microbial and inflammatory components this study aimed to further understand the antimicrobial activity of honey against different species in subgingival biofilms. We conducted a DNA–DNA hybridization assay on in vivo biofilm samples to assess specific reductions based on Socransky’s complexes, analyzing biofilms treated with OHD at 40%, chlorhexidine at 0.12%, and a diluent.

Studies have shown that periodontal disease begins with periodontal dysbiosis. Dysbiosis develops gradually, shifting the relationship between microorganisms and the host to a pathogenic state. The orange complex is first associated with dysbiosis and disease onset, followed by the red complex, indicating a mature biofilm and disease progression [

32,

72].

P. gingivalis adheres to yellow complex pathogens like

S. gordonii, increasing virulence and causing bone loss [

73].

Our DNA–DNA hybridization results showed a significant reduction in 14 species from a 34-species biofilm when treated with OHD at 40% compared to the control (

p < 0.05). Notably, the biofilm reduction included species from the red complex (

T. forsythia,

P. gingivalis,

P. intermedia,

P. micros, and

F. nucleatum) and the orange complex (

S. gordonii), which are closely linked to periodontal dysbiosis and disease establishment [

74,

75,

76]. The decrease in total bacteria count from the yellow, orange, and red complexes suggests that honey consumption can control these microorganisms’ growth, preventing periodontal disease establishment and progression.

We conducted a periodontal disease model in mice to verify the efficacy of OHD in preventing periodontal disease. Instead of solely applying a ligature silk suture thread to the mice’s first molar, we also exposed the mice to a

P. gingivalis inoculum (10

7) for 48 h under anaerobic conditions. For four consecutive days, the mice received 100 µL of

P. gingivalis. Another study demonstrated that combining

P. gingivalis with the ligature silk suture thread in the periodontal model exacerbated bone resorption dependent on the RANKL protein [

77].

Daily treatment with OHD at 40% five times a day decreased bone loss by 34% compared to the untreated group (

Figure 2A). However, the group that received raw honey did not show a statistical difference compared to the untreated group. The treatment frequency was based on a balanced diet of three regular meals and two light meals, totaling five honey feedings a day. A representative image of each experimental group (

Figure 2A) showed the preservation of the alveolar bone crest in the furcation area. Damage in that area indicates disease progression, and without regular periodontal treatment, there is an increased risk of molar loss involving the furcation area [

78].

A double-blind dental caries score was determined after the periodontal assay by a calibrated examiner, as previously described [

39]. None of the mice showed caries lesions or white spots. These findings suggest that despite honey being rich in carbohydrates, rational feeding and short-term use are safe. To verify the antimicrobial potential of OHD in vivo, a ligature silk suture thread was collected for DNA–DNA hybridization. As shown in

Figure 2D, the group treated with 40% OHD had a significant decrease in

S. gordonii,

S. sanguinis,

F. nucleatum,

P. gingivalis, and

Prevotella melaninogenica, confirming the in vitro results. In the group treated with natural OHD, only

P. gingivalis showed a significant reduction compared to the control.

Several studies have linked

P. gingivalis’s presence and virulence to increased bone loss in periodontal disease [

79,

80]. Therefore, the reduced bone loss in the OHD group may be due to the decreased viability of the

P. gingivalis biofilm and other periodontal pathogens, as well as its previously evaluated anti-inflammatory activity [

71]. These microorganisms stimulate the host immune system to release inflammatory mediators, which in turn stimulate osteoclast activity [

81]. Our results suggest that the combined antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity of OHD prevented excessive bone loss in the in vivo mouse model.

Surprisingly, OHD at 40% was more effective than raw honey. This enhanced effect may result from both the production of H

2O

2 by the glucose oxidase enzyme and the honey’s viscosity. The formation of H

2O

2 depends on the honey dilution, as the enzyme is inactive in raw honey [

82], and its activation varies with dilution rate [

83]. Previous studies have shown a strong correlation between H

2O

2 levels and bacterial growth inhibition by honey [

82].

Even at high dilutions, H

2O

2 remains in the solution and inhibits microbial viability to varying degrees [

84]. We hypothesize that raw honey does not activate its glucose oxidase enzyme sufficiently to produce antimicrobial quantities of H

2O

2. Additionally, the viscosity of honey may hinder biological compounds from effectively reaching the ligature region. Another factor is the mice’s self-cleaning behavior, which can prevent honey from reaching the ligature area. In contrast, mice treated with 40% OHD, which had active glucose oxidase producing H

2O

2 and a fluid consistency to reach the ligature, did not exhibit a self-cleaning behavior.

No other studies in the scientific literature have evaluated the biological activity of honey specifically in an in vivo model of periodontal disease. In our study, honey treatment began on the fourth day after the installation of a ligature silk suture thread, when bone resorption began [

37]. Considering that honey is a food, not a medicine, OHD could potentially reduce the risk of periodontal diseases if included rationally in the diet of healthy individuals.