At first glance, it may not seem like food and fashion have all that much in common. But these two fields, which can communicate our cultural and personal identities while bringing great joy and comfort, also represent major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, material waste and unethical labor practices around the world.

By convening leaders, experts, designers and educators from both industries for a day-long discussion of wide-ranging fashion and food-systems issues as part of this year’s NYC Climate Week, the Forward Food & Fashion event aimed to address their complex challenges and brainstorm ways to ensure a more sustainable future. Presented by Clim-Eat in collaboration with Barnard College and Columbia Climate School, the day’s sessions included conversations, interactive activities, interdisciplinary presentations and even food tastings.

“How can we work across sectors and break some of the silos that have built up?” asked Dhanush Dinesh, the founder of the nonprofit Clim-Eat, who hosted the event. How do we find a path forward together?

In opening remarks, Jessica Fanzo, professor of climate and director of the Food for Humanity Initiative at the Columbia Climate School, said she considered Forward Food & Fashion one of the most unique events on the Climate Week schedule.

“You’ve heard about the term ‘fast fashion.’ You’ve heard the term ‘fast food.’ How do we slow down these two sectors? How do we make them more sustainable?” Fanzo asked the audience.

What’s more, how do we quantify the true environmental costs of these two industries, she continued. While consumer costs of, say, buying a burger or sweater may be relatively low, “Someone’s paying for the true cost to produce fashion. Someone’s paying for the true cost to produce food,” she said. “Is it the planet? Is it the people producing these foods?”

In a sentiment that would be echoed by many of the day’s speakers, Fanzo said, “We have the solutions,” including better land, soil and water management; increased protection of biodiversity; and more ethical labor practices. What we need is action, scale-up and accountability—especially from the private sector, she added.

Consumers also have a role to play by educating themselves, buying less or secondhand, consuming the food they do buy and demanding more transparency about where their food and fashion is coming from, Fanzo said.

Sandra Goldmark, associate dean for interdisciplinary engagement at the Climate School and professor of professional practice at Barnard College, discussed working as a theater set designer in the first part of her career, until she realized how much of the scenery would be thrown into the dumpster after each show. She remembered thinking, “What am I doing? I did not get into this to make garbage.”

Now, Goldmark is an advocate for circularity and fixing what’s broken instead of throwing it away. “Every single human will wake up today, will eat food and get dressed,” she said. While the presentation and price may differ tremendously, food and fashion are fundamental stories we are telling every day in terms of our histories and our cultures.

How do we change our global narrative to one we won’t regret? she asked. “This is a chance to change our shared story…to reduce emissions, improve livelihoods around the world, reduce waste, raise standards of living and even sequester carbon.” Already, we are seeing our students leading the way in this movement, Goldmark said.

The panel on Women Leading in Climate, featured Catherine McKenna, adjunct senior research scholar at the Climate School and chair of the U.N. High-Level Expert Group on the Net-Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities; Amanda Sturgeon, CEO of the Biomimicry Institute; Marci Zaroff, CEO/founder of Ecofashion Corp and board chair/co-founder of the Textile Exchange; Amanda Parkes, chief innovation officer of Pangaia, and Ruth DeFries, chief academic officer and co-founding dean emerita of the Climate School, shared diverse perspectives on fashion and its effects on climate—from agriculture practices to textile recycling.

Although all the panelists championed the accomplishments of women leaders in the climate space, “it’s time to get men on board,” McKenna said, “and to demand governments step up.”

Often “the poorest people in the world are the ones producing the food and fiber, and they can’t afford to make [sustainable] choices,” DeFries said. “And on the consumption end, most people in the world don’t have a lot of flexibility to spend extra on food and fiber.” These challenges need to be considered in a “systems” sort of way, she said; for example, what can we do to nudge the incentives system for people to make better choices for the environment?

While it’s unpopular to say because it will make things more expensive, DeFries acknowledged, to change the system, we need to internalize the external costs of food and fashion—from the production to the disposal stages—that otherwise aren’t seen by today’s consumers. We will need to be bold if we want to effect real change, she said.

The panelists also discussed the importance of improving traceability and transparency in the food and fashion industry, and of turning to science and nature for ideas about how to create—and destroy—materials more sustainability and regeneratively.

In keeping with the event’s theme, the food served for lunch was provided by Le Botaniste, an organic, plant-based and carbon-neutral restaurant in New York, in reusable containers and dishware by Re:Dish, which had scannable QR codes to tell you how many times your container had been reused.

The afternoon also offered a presidential debate in sustainability where experts in food—Ana Maria Loboguerrero, director of adaptive and equitable food systems at Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—and fashion—Christine Goulay, founder and CEO of Sustainabelle Advisory Services—sounded off on their lessons from the field.

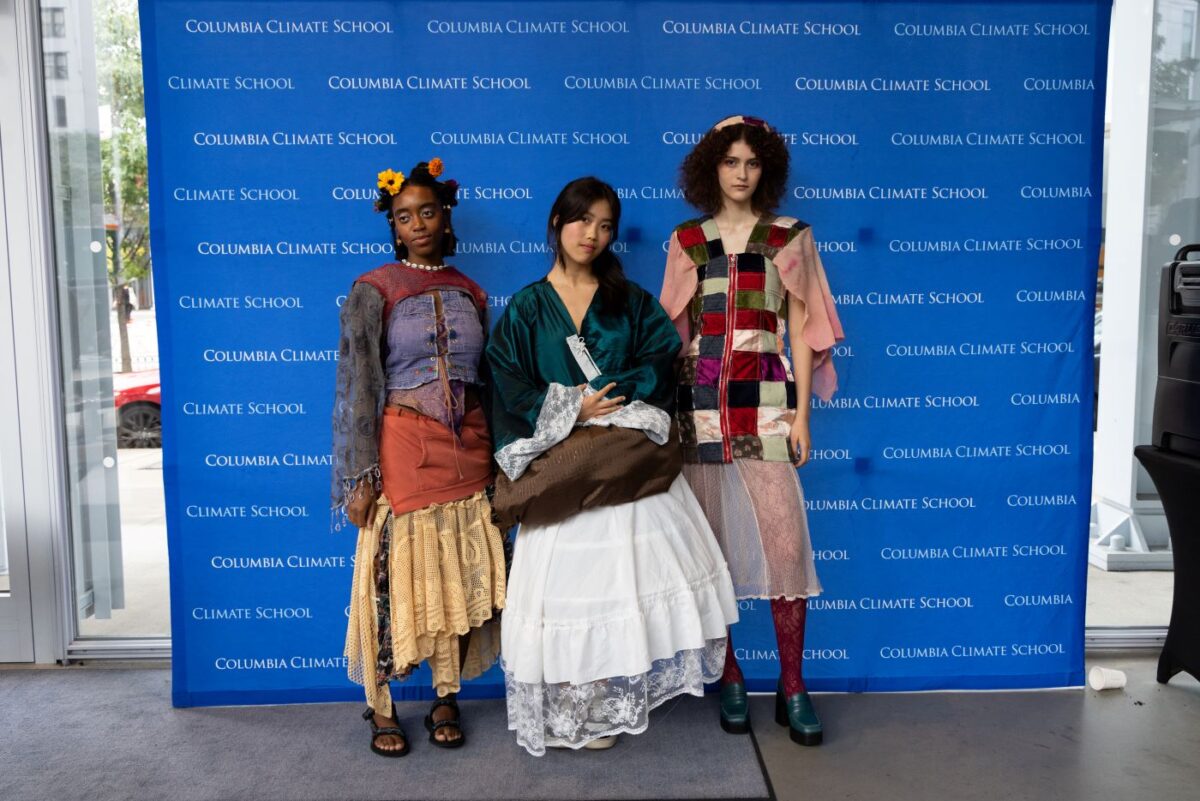

And for the grand finale, three student teams participated in a Food and Fashion Sustainability Fusion challenge; each team created a design and a dish that embodied their vision for the future. Audience members got to taste and view these creations, including a root vegetable casserole, a tomato-liquid mocktail and a quilted zip-up tunic dyed with blueberry juice. Guest judges Erin Beatty, founder of Rentrayage; Ngozi Okaro, founder of Custom Collaborative; Indré Rockefeller, Columbia Climate School alum and founder of the Circularity Project and Michael DeMartino, executive chef of Columbia Dining, provided feedback.

In the end—unlike a traditional design competition or bake-off—there was no sole winner. As Goldmark argued, a sustainable future for food and fashion depends on a diverse ecosystem of complementary solutions; “there is no single silver bullet—and either we all win, or nobody does.”

Source link

Olga Rukovets news.climate.columbia.edu