1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

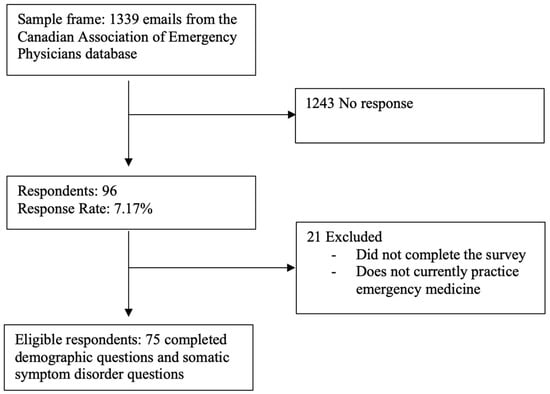

A voluntary and anonymous national survey was emailed to a list of 1339 EPs supplied by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Participants were excluded if they did not actively practise emergency medicine. Ethics approval was obtained from Dalhousie University on July 28 2023 (REB # 2023-6757).

The survey was distributed on 16 October 2023, with reminders after two and four weeks, and closed on 17 November 2023.

Statistical Analysis

Mean values and standard deviations for all 18 questions were calculated and responses were analyzed for associations with demographic information. A t-test was used for two-category demographics, and ANOVA was used for those with three or more categories, all at a 95% confidence interval. Bonferroni tests were conducted when necessary. Responses with fewer than six options (e.g., question 8) were scaled for comparison.

3. Results

In total, 96 participants completed the survey, of which 75 were deemed eligible.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate EPs’ attitudes and comfort in managing patients with suspected SSD and identify demographic factors associated with their responses.

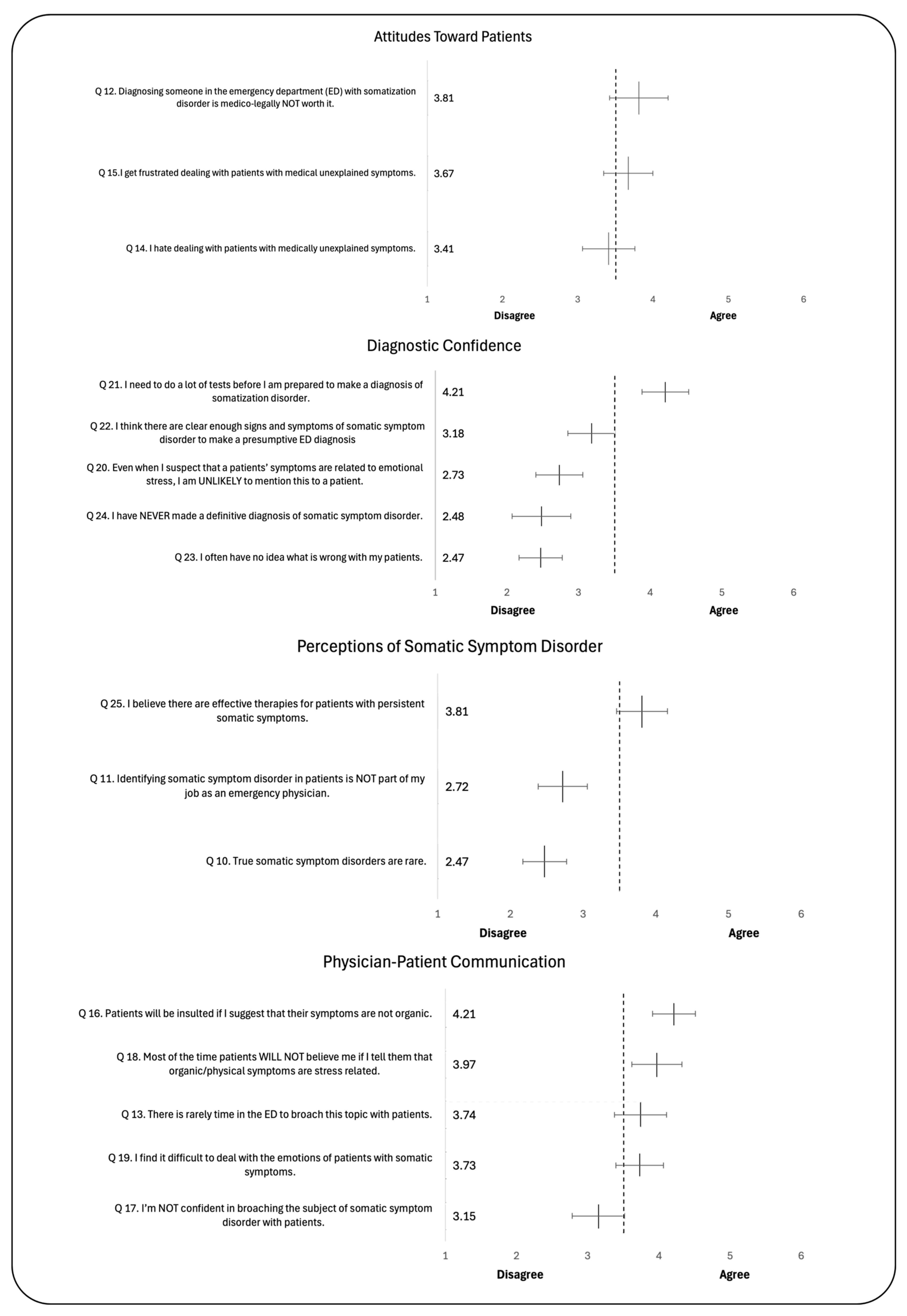

Most respondents felt that SSD is common and underdiagnosed, acknowledged the existence of effective therapies to treat SSD and acknowledged their role in diagnosing it. Respondents perceived the need for extensive testing before diagnosis. While this is understandable considering the imperative in EM to consider acutely life-threatening diagnoses, male respondents were more likely to believe there are clear enough signs of SSD to make a presumptive diagnosis.

CCFP(EM)-trained EPs were more likely to report having made a diagnosis than FRCPC physicians. This difference may be explained by a CCFP(EM) physician’s greater exposure to SSD patients in primary care training, and by the possibility that FRCPC-trained EPs are more likely to work in higher-acuity EDs, thus having an appropriately higher index of suspicion for acute life-threatening illness.

5. Conclusions

EPs recognize that, while ruling out life-threatening illness is crucial, SSD is common and underdiagnosed. They believe effective therapies exist and see SSD as a legitimate ED diagnosis. However, they remain concerned that patients may react negatively to non-organic explications, reported struggling with managing patient’s emotions, and reported that there is often a lack time to address the diagnosis. Opportunities remain to improve care for SSD and reduce the associated suffering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.W. and S.G.C.; data curation, J.H.W.; formal analysis, J.H.W., J.M.T. and S.G.C.; funding acquisition, J.H.W.; investigation, J.H.W.; methodology, J.H.W. and S.G.C.; project administration, J.H.W.; resources, J.H.W.; supervision, S.G.C.; visualization, J.H.W.; writing—original draft, J.H.W.; writing—review and editing, J.H.W., J.M.T. and S.G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We received financial support in the form of a CAD 5000 bursary from the Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine Ross Stuart Smith RIM Summer Studentship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dalhousie University (REB # 2023-6757, 28 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| SSD | somatic symptom disorder |

| ED | emergency department |

| EP | emergency physician |

| FRCPC | Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada |

| CCFP | Certification in the College of Family Physicians |

| CCFP-EM | Certification in the College of Family Physicians with additional certificate in Emergency Medicine |

| PCP | primary care physician |

Appendix A

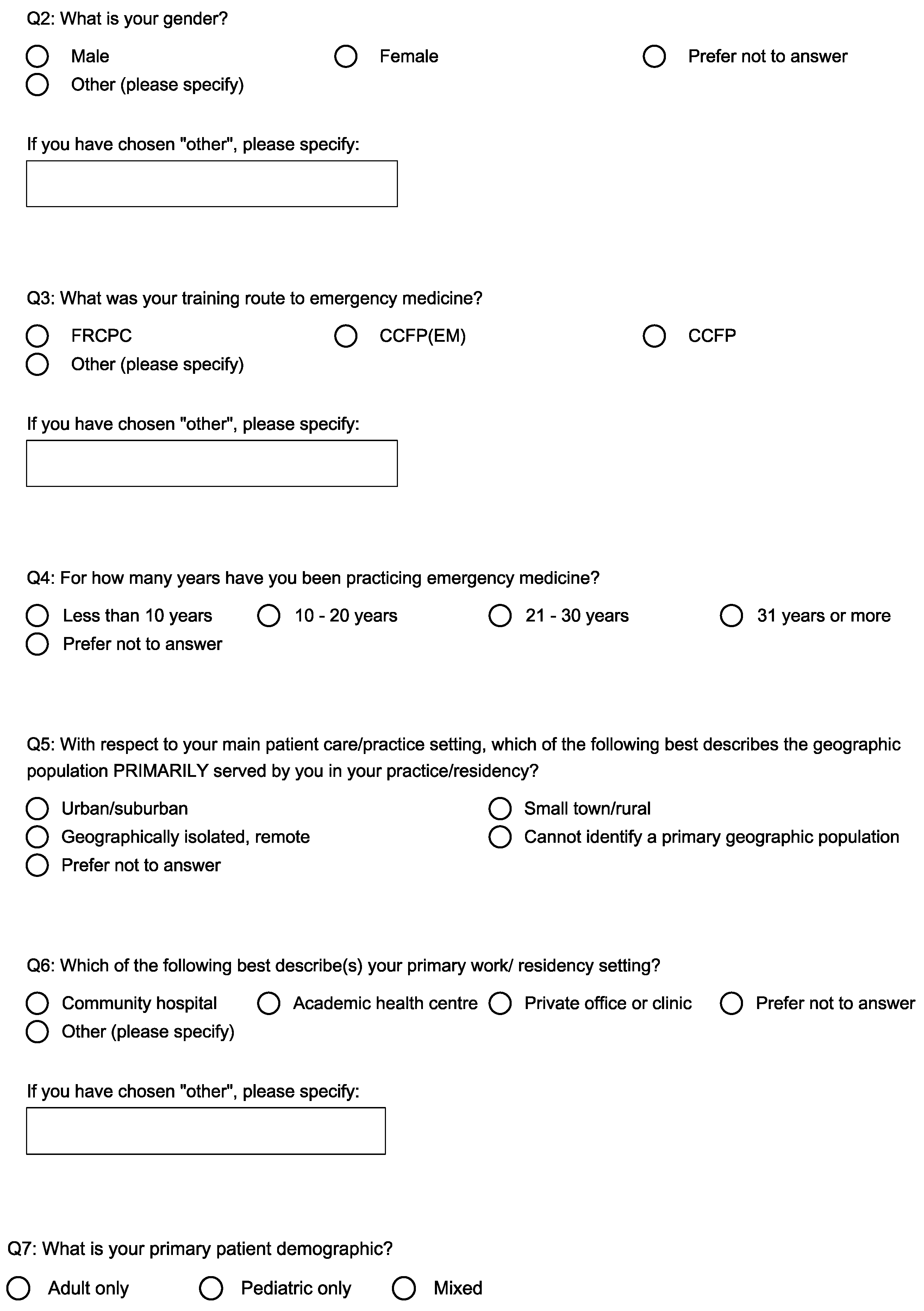

Section 1 of the survey collecting demographic information.

Figure A1.

Section 1 of the survey collecting demographic information.

Section 2 of the survey collecting the survey response data.

Figure A2.

Section 2 of the survey collecting the survey response data.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (Ed.) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th ed.; Text Revision; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Alsma, J.; van de Wouw, J.; Jellema, K.; Coffeng, S.M.; Tobback, E.; Delesie, L.; Brand, C.L.V.D.; Vogelaers, D.; Mariman, A.; Paepe, P.; et al. Medically unexplained physical symptoms in patients visiting the emergency department: An international multicentre retrospective study. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virk, P.; Vo, D.X.; Ellis, J.; Doan, Q. Pediatric somatization in the emergency department: Assessing missed opportunities for early management. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 22, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, S.; Akhlaghi, H.; Watson, T.; O’Reilly, G.M.; Karro, J. Attitudes and regard for specific medical conditions among Australian emergency medicine clinicians. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2022, 34, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, M.; Pohontsch, N.J.; Zimmermann, T.; Scherer, M.; Löwe, B. Diagnostic and treatment barriers to persistent somatic symptoms in primary care—Representative survey with physicians. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, D.; Vogel, L. National survey highlights worsening primary care access. CMAJ 2023, 195, E592–E593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.J.; Syue, Y.J.; Tsai, T.C.; Wu, K.H.; Lee, C.H.; Lin, Y.R. The Impact of Emergency Physician Seniority on Clinical Efficiency, Emergency Department Resource Use, Patient Outcomes, and Disposition Accuracy. Medicine 2016, 95, e2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desjarlais-deKlerk, K.; Wallace, J.E. Instrumental and socioemotional communications in doctor-patient interactions in urban and rural clinics. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.M.; Hadee, T.; Carroll, J.; Meldrum, S.C.; Lardner, J.; Shields, C.G. “Could this Be Something Serious?”: Reassurance, Uncertainty, and Empathy in Response to Patients’ Expressions of Worry. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, C.; Sattel, H.; Schaefert, R.; Henningsen, P.; Hausteiner-Wiehle, C. Functional Somatic Symptoms. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 553. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/10.3238/arztebl.2019.0553 (accessed on 10 August 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Town, J.M.; Abbass, A.; Campbell, S. Halifax somatic symptom disorder trial: A pilot randomized controlled trial of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy in the emergency department. J. Psychosom. Res. 2024, 187, 111889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iloson, C.; Praetorius Björk, M.; Möller, A.; Sundfeldt, K.; Bernhardsson, S. Awareness of somatisation disorder among Swedish physicians at emergency departments: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

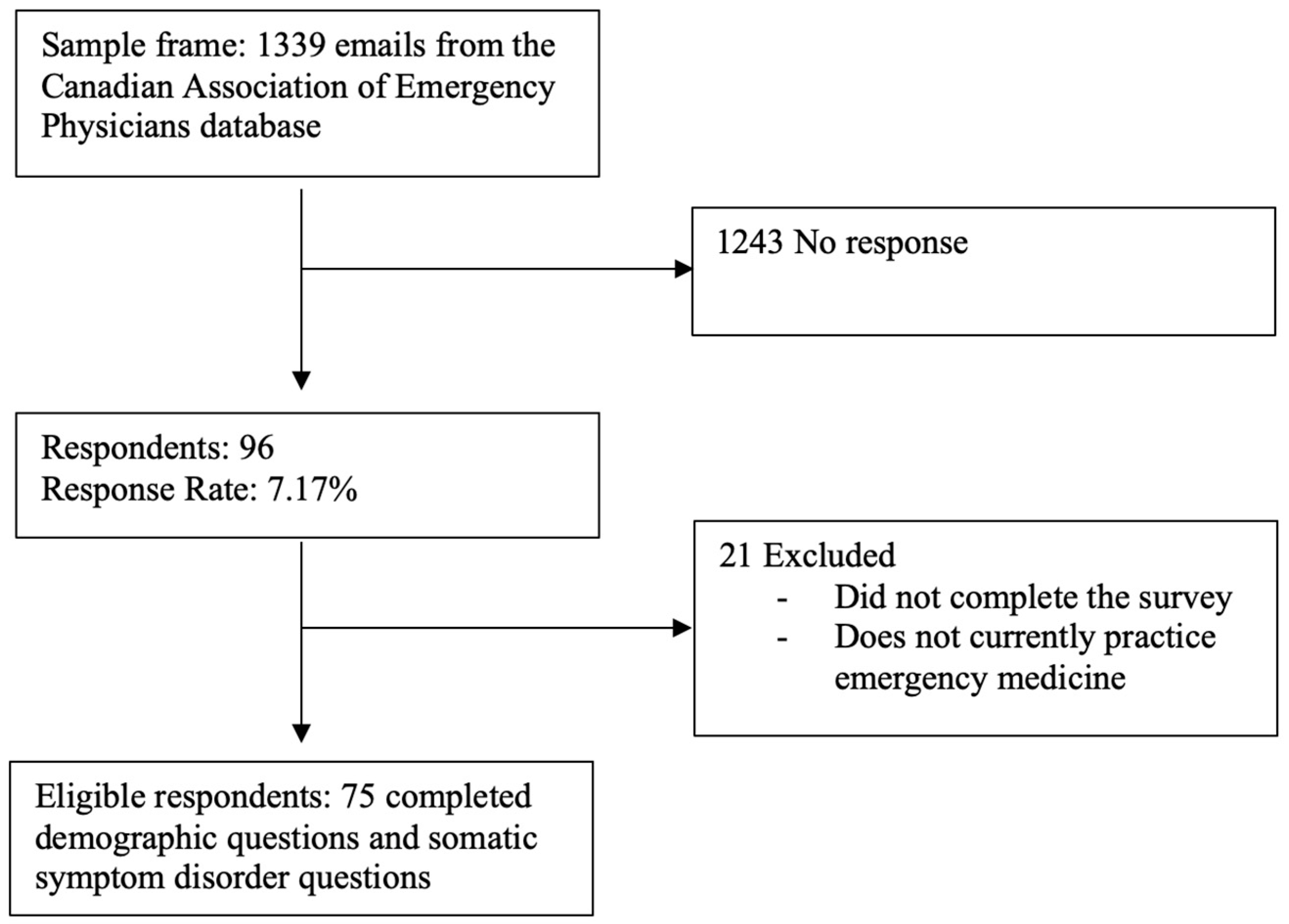

Study flow chart.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Mean responses to questions in Section 2 (Figure A2) of the survey. Questions are subdivided into four domains and ordered from highest average level of agreement to highest average level of disagreement. Mean responses are displayed beside the statement. The value 3.5 is represented by the dotted reference line. The closer the mean is to 6, the stronger the agreement. The closer the mean is to 1, the stronger the disagreement. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Mean responses to questions in Section 2 (Figure A2) of the survey. Questions are subdivided into four domains and ordered from highest average level of agreement to highest average level of disagreement. Mean responses are displayed beside the statement. The value 3.5 is represented by the dotted reference line. The closer the mean is to 6, the stronger the agreement. The closer the mean is to 1, the stronger the disagreement. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

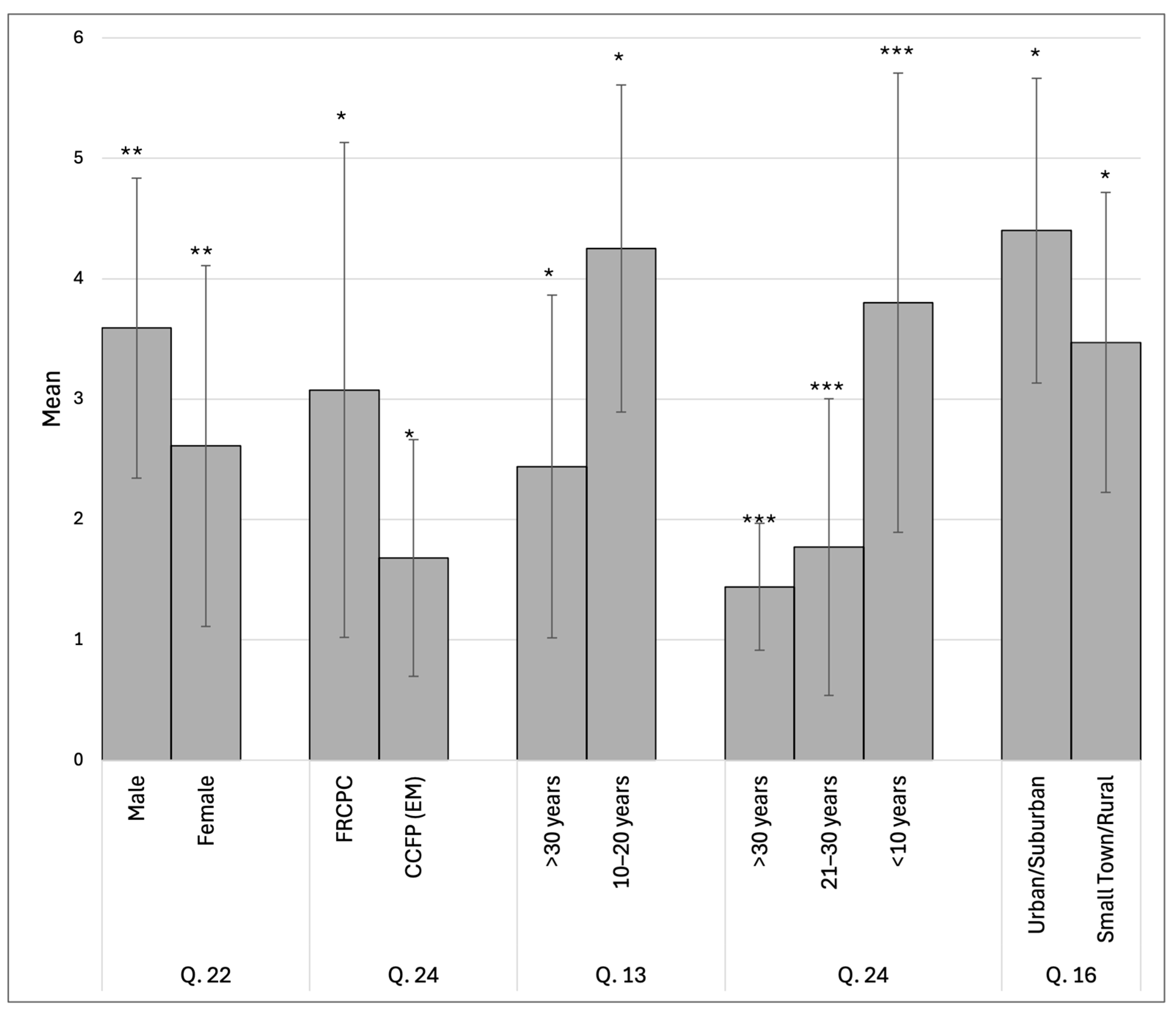

Bar graph showing mean responses in Section 2 (Figure A2) of the survey when significant differences existed based on demographic variables collected in Section 1 (Figure A1). Only significant differences are shown. Question number is indicated on the x axis along with the demographic variable. Error bars represent the standard deviation. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Bar graph showing mean responses in Section 2 (Figure A2) of the survey when significant differences existed based on demographic variables collected in Section 1 (Figure A1). Only significant differences are shown. Question number is indicated on the x axis along with the demographic variable. Error bars represent the standard deviation. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Personal and practice characteristics of participants, n = 75.

Table 1.

Personal and practice characteristics of participants, n = 75.

| Level | Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (%) | 44 (58.7) |

| Female (%) | 31 (41.3) | |

| Training Path | FRCPC (%) | 40 (53.3) |

| CCFP (EM) (%) | 28 (37.3) | |

| CCFP (%) | 5 (6.7) | |

| Other (%) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Years Spent Practising Emergency Medicine | >10 years (%) | 20 (26.7) |

| 10–20 years (%) | 24 (32) | |

| 21–30 years (%) | 22 (29.3) | |

| >31 years (%) | 9 (12) | |

| Geographic Population Served in Practice Setting | Urban/Suburban (%) | 60 (80) |

| Small Town/Rural (%) | 15 (20) | |

| Geographically Isolated/Remote | 0 | |

| Cannot Identify a Primary Geographic Location | 0 | |

| Primary Work Setting | Community Hospital (%) | 31 (41.3) |

| Academic Health Centre (%) | 44 (58.7) | |

| Private Office/Clinic | 0 | |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 0 | |

| Primary Patient Demographic | Adult Only (%) | 19 (25.3) |

| Pediatric Only (%) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Mixed (%) | 52 (69.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Source link

Jesse H. Wells www.mdpi.com