This paper employs SPSS 21.0 and Mplus 8.3 to analyze and evaluate the validity and reliability of the measurement model. We tested the hypothesis using a hierarchical regression model.

4.1. Common Method Variance Test

Given that the variables were solely obtained by self-report measures from the participating entrepreneurs in response to the provided questionnaire, it is plausible that the study may be susceptible to the issue of common method variance (CMV). Consequently, we used Harman’s one-way test to include all the variables in the study in the measurement of the items in the factor analysis. The findings indicate that out of the five main components derived from the unrotated component matrix, the initial factor principal component accounts for 37.560% of the variation, which is less than half the overall variance (81.529%), which suggests that this study does not suffer from significant CMV. Then, the nested model was used to compare the goodness-of-fit of the one-factor model and the measurement model. The results show that, with the addition of the method factor, the baseline model has a better model fit index (χ2/df = 1.495, RMSEA = 0.040, CFI = 0.973, TLI = 0.972, SRMR = 0.065) than the four-factor model. However, when χ2/df falls by 0.015, CFI and TLI increase by only 0.001, RMSEA decreases by 0.001, and SRMR increases by 0.006. Overall, the fit did not improve significantly, suggesting the absence of serious CMV.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

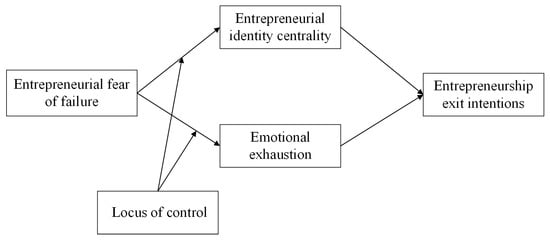

To further understand the mechanism of action between the main variables, we used Mplus 8.3 and SPSS 21.0 to test H1, H2, H3a, and H3b in turn based on the hierarchical regression method [

51].

Table 3 shows the results.

First, we test the mediating effects of entrepreneurial identity centrality as well as emotional exhaustion between EFF and entrepreneurial exit intentions. After all control variables (gender, age, and education) are controlled for, EFF has a significantly positive effect on entrepreneurial identity centrality (M2,

β = 0.174,

p < 0.001) and emotional exhaustion (M5,

β = 0.639,

p < 0.001), as shown in Models M2 and M5 in

Table 3. As shown in models M9 and M10 in

Table 3, entrepreneurial identity centrality has a significantly negative effect on entrepreneurial exit intentions (M9,

β = −0.366,

p < 0.001), and emotional exhaustion has a significantly positive effect on entrepreneurial exit intentions (M10,

β = 0.191,

p < 0.001). In order to further confirm the mediating role of entrepreneurial identity centrality and emotional exhaustion between EFF and entrepreneurial exit intentions, we follow Mackinnon et al. (2007) and further test the significance of the mediating effect using the nonparametric bootstrap method (with 5000 random samples) [

52]. The results are shown in

Table 4. When the mediating variable is entrepreneurial identity centrality, the indirect effect is −0.041, and the 95% CI is [−0.073, −0.013], which indicates that the mediating impact of entrepreneurial identity centrality between EFF and entrepreneurial exit intentions is significant, and H1 is confirmed. When the mediating variable is emotional exhaustion, the indirect effect is 0.122, and the 95% CI is [0.066, 0.181], excluding 0, indicating that the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion between EFF and entrepreneurial exit intentions is significant, and H2 is confirmed.

Second, we investigate the moderating effects of LoC on the correlation among EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality. As shown in Model M3 in

Table 3, there is a statistically significant and positive relationship among EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality (

β = 0.190,

p < 0.001) when controlling for the relevant control variables. The predictive effect of the interaction term between EFF and LoC on entrepreneurial identity centrality is considerably positive (

β = 0.213,

p < 0.001). This finding indicates that higher internal control, as measured by the LoC, is associated with a stronger positive association between EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality—that is, individuals with better internal control are more inclined to be motivated by their fear of failure to develop a stronger sense of entrepreneurial identity. In order to reflect the moderating effect of the control variables on the correlation among EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality, we follow Aiken and West (1991), who suggest taking the value of the LoC plus or minus one standard deviation to proxy for the moderating effect of entrepreneurial identity centrality, as shown in

Figure 2 [

53]. As shown in

Figure 2, the positive correlation among EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality is stronger for internals than for externals, which is consistent with the initial expectation.

Meanwhile, in order to determine the significance level of the moderating effect of entrepreneurial identity centrality more accurately, we perform a simple slope analysis of the moderating effect based on different LoC levels (plus or minus one standard deviation). Performing a simple slope analysis shows that the positive correlation among EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality is stronger for internals (M-SD) (γ = 0.609, t = 4.999, p < 0.01). In contrast, the positive correlation among EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality was weaker for externals (M + SD) (γ = 0.321, t = 5.508, p < 0.01). Thus, H3a is confirmed.

Third, we examine the moderating impact of LoC between EFF and emotional exhaustion. As shown in Model M6 in

Table 3, there is a statistically significant and positive relationship among EFF and emotional exhaustion (β = 0.639,

p < 0.001) when controlling for the relevant control variables. The predictive effect of the interaction term between EFF and LoC on emotional exhaustion is considerably negative (β = −0.241,

p < 0.001). This finding indicates that higher internal control, as measured by the LoC, is associated with a less positive association between EFF and emotional exhaustion—that is, EFF is less likely to result in emotional exhaustion.

To reflect the moderating impact of the control variables on the relationship between EFF and emotional exhaustion, we follow Aiken and West (1991), who suggest taking the value of the LoC plus or minus one standard deviation to proxy for the moderating effect of emotional exhaustion, as shown in

Figure 3 [

53]. As shown in

Figure 3, the positive correlation between EFF and entrepreneurial identity centrality is stronger for internals than for externals, which is consistent with our initial expectations. Meanwhile, in order to determine the significance level of the moderating effect of emotional exhaustion more accurately, we perform a simple slope analysis of the moderating effect based on different LoC levels (M ± SD). The simple slope analysis shows that the positive association between EFF and emotional exhaustion was stronger for externals (M-SD) (γ = 0.468,

t = 5.346,

p < 0.01). In contrast, the positive correlation between EFF and emotional exhaustion was weaker for internals (M + SD) (γ = 0.102,

t = 0.520,

p > 0.05, n.s.). Therefore, H3b is confirmed. The model results are shown in

Figure 4.

Finally, we test whether LoCs moderate the mediating role of entrepreneurial identity centrality and emotional exhaustion between EFF as well as entrepreneurial exit intentions. Following Edwards and Lambert (2007) [

45], we use Mplus 8.3 to build a holistic measurement model for moderated path analyses and assess individual direct and indirect effects [

32]. The results are shown in

Table 5.

First, if the mediating variable is entrepreneurial identity centrality, when the degree of LoC is high (internal control), the indirect effect is significant (β = −0.182, 95% CI = [−0.351, −0.076]). When the degree of LoC is low (external control), the indirect effect is no longer significant. With different values for the entrepreneurial control variables, the difference in the indirect effect is significant (Δ = −0.268, 95% CI = [−0.550, −0.066]), reflecting that LoC moderates the indirect effect of EFF via entrepreneurial identity centrality, which affects entrepreneurial exit intentions. That is, the indirect effect in which EFF affects entrepreneurial exit intentions via entrepreneurial identity centrality is greater for internals than externals—thus confirming H4a.

Second, if the mediating variable is emotional exhaustion, when the degree of LoC is low (external control), the indirect effect is significant (β = 0.217, 95% CI = [0.100, 0.364]). When the degree of LoC is high (internal control), the indirect effect is not significant. The significant difference in the indirect effect (Δ = −0.175, 95% CI = [−0.384, −0.048]), at different values of entrepreneurial control variables, suggests that LoC moderates the indirect effect of EFF via emotional exhaustion on entrepreneurial exit intentions. That is, the indirect effect of EFF affecting entrepreneurial exit intentions via emotional exhaustion is greater for externals than internals—thus confirming H4b.