Growing up in Chicago, Chakena D. Perry knew not to trust the water coming out of her tap.

“It was just one of these unspoken truths within households like mine — low-income, Black households — that there was some sort of distrust with the water,” said Perry, who later learned that Chicago is the city with the most lead service lines in the country. “No one really talked about it, but we never used our tap for just regular drinking.”

Now, as a senior policy advocate for the Natural Resources Defense Council, Perry is part of a coalition that fought for stricter rules to force cities like Chicago to remove their toxic lead pipes faster. Last year, advocates celebrated a big win: The Biden administration’s Environmental Protection Agency mandated that water systems across the country replace all their lead service lines. Under the new rule, most water systems will have 10 years to complete replacements, while Chicago will likely get just over 20, starting in 2027, when that requirement kicks in.

But the city’s replacement plan, submitted to the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency in April per state law and obtained through a public records request, puts it 30 years behind that timeline.

Chicago’s plan adheres to state law and an outdated EPA rule from the first Trump administration. It aims to replace the city’s estimated 412,000 lead service lines by 2076 — completing 8,300 replacements annually for 50 years, starting in 2027.

The latest federal rule requires Chicago to replace nearly 20,000 pipes per year beginning in 2027 — more than double the speed of the city’s current plan. Documents show city officials are aware of the new requirements, but have not yet updated their plans.

A delayed timeline will expose many more children and adults to the risk of toxic drinking water, and rising temperatures from climate change may exacerbate the risk by causing more lead to leach off pipes and into water.

Coming soon: More reporting on Chicago’s lead service lines, plus an interactive map to explore which areas are most at risk. Sign up to be notified when these stories and tools are available.

For Perry, even 20 more years of lead pipes was a compromise.

“People are already being exposed — they’re being exposed daily,” Perry said. “There is no number [of years] that is satisfactory to me, but 20-ish years is better than 50.”

In recent decades, drinking water crises in Washington, D.C., and Flint, Michigan, put the public health threat of lead on the national map. Lead pipes are a danger across the country, where about 9 million lead service lines need to be replaced to adhere to the new requirements. About a million of those are in Illinois — the most of any state in the country. Among the five U.S. cities estimated to have the most lead pipes — Chicago, Cleveland, New York, Detroit, and Milwaukee — only Chicago has yet to adopt the latest federal deadline. The rest plan to replace their lead pipes within a decade of 2027.

Lead can damage the human brain and nervous system, kidney function, and reproductive health, and it’s also an underappreciated cause of cardiovascular problems.

Lead is particularly harmful to children: It can hamper brain development and cause permanent intellectual disabilities, fatigue, convulsions, comas, or even death. Lead exposure during pregnancy can also cause low birth weight or preterm birth.

Experts emphasize that there is no safe level of lead exposure.

In Illinois, the Metropolitan Planning Council found that people of color are up to twice as likely as white people to live in a community burdened by lead service lines.

Because of a three-year grace period in the 2024 EPA rule — the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements, or LCRI — the city does not have to begin complying with the new replacement requirements until 2027. But Chicago’s plan outlines a timeline that starts the very same year and is significantly slower.

“I’m not sure what Chicago is thinking there,” said Marissa Lieberman-Klein, an Earthjustice attorney focused on lead in drinking water.

Chicago is facing a Herculean task. Even with a 50-year timeline, it will have to start moving much faster than its current replacement speed: The city will need to replace more lead service lines annually than the total of 7,923 it managed over the past four years ending in March. Of these replacements, about 60 percent occurred alongside repairs for breaks and leaks or water and sewer main replacements.

Megan Vidis, a spokesperson for the Chicago Department of Water Management, said Chicago is ramping up its replacement speeds. The city will replace 8,000 lines this year, she said.

“We have been and will continue to move as quickly as resources allow to replace lead service lines,” Vidis wrote in an email.

Asked about the feasibility of the current EPA rule’s 20-year replacement timeline, Vidis wrote, “We need substantial additional funding, particularly the kind available to help pay for private side replacements.” That refers to the city’s split ownership structure, where homeowners own one part of the line and the city owns the other.

Erik D. Olson, senior strategic director for environmental health at the NRDC, said these financial woes are a reason for Chicago to put forward a more ambitious replacement plan.

Olson pointed out that $15 billion in national lead service line replacement funds from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, also known as the bipartisan infrastructure law, expire next year.

“If Chicago isn’t beating down the doors to get that money, that is tragic, because that money could evaporate,” Olson said. “They should be front-end loading as much of the service line replacement as they possibly can.”

U.S. EPA spokesperson David Shark confirmed that Illinois water systems are currently under the new rule. But the agency did not answer specific questions about Illinois’ obligations between now and when the compliance deadlines start in 2027, citing pending litigation on the rule.

Illinois EPA spokesperson Kim Biggs wrote in an email that the state is operating under the replacement requirements included in the 2021 EPA rule and the state’s law until 2027.

Lead service lines were required by Chicago’s municipal code — reportedly influenced by lead companies and the plumbers union — for decades after much of the country stopped using them due to health concerns. According to a study published last year, two-thirds of the city’s youngest children — under 6 years old — live in homes with tap water containing detectable levels of lead.

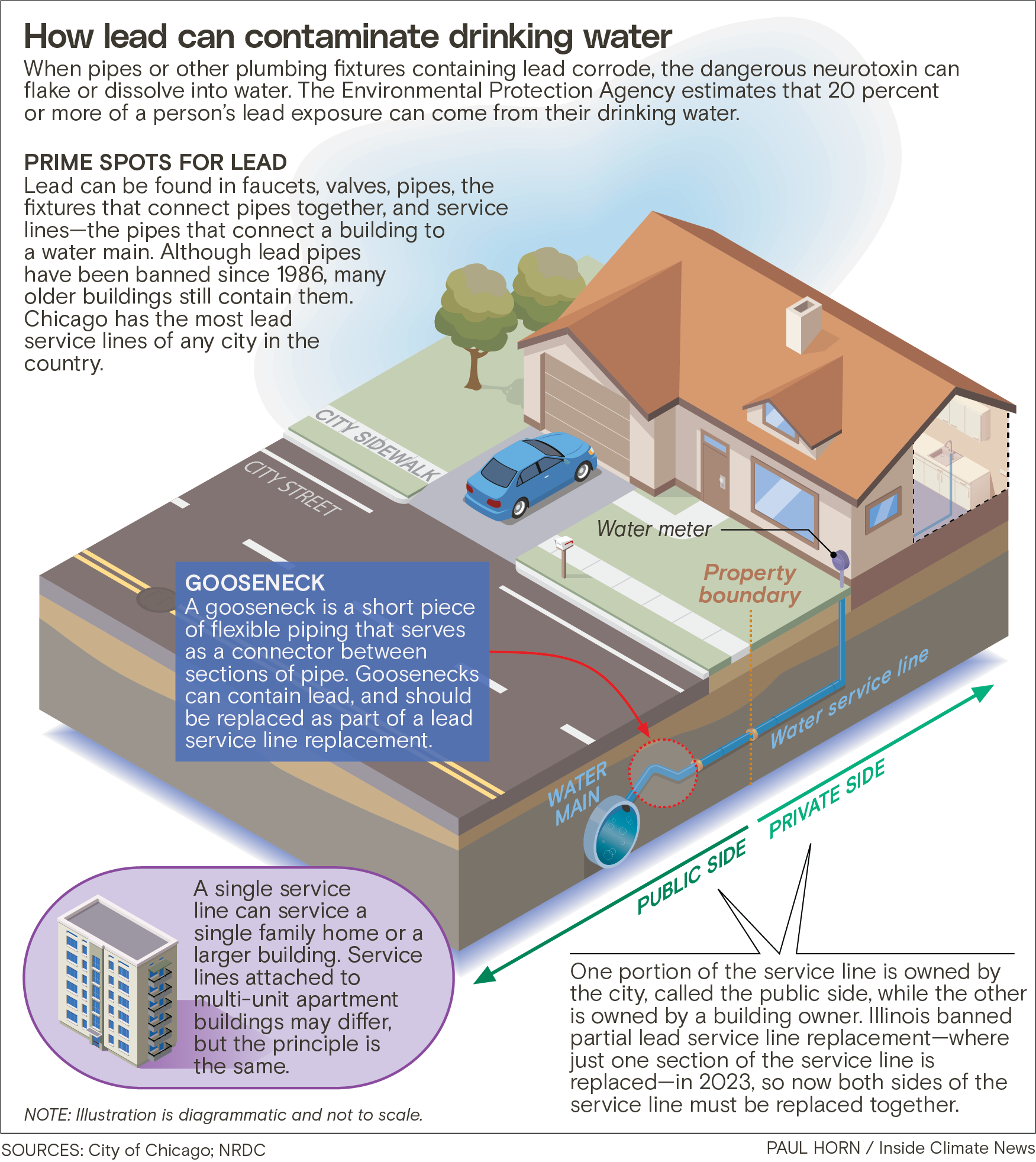

Drinking water is just one way that people are exposed to lead. It’s also found in soil and paint. But experts estimate that water could make up at least 20 percent of a person’s exposure.

When lead pipes corrode, the toxic material can dissolve or flake into water and poison residents without their knowledge. Rising temperatures due to climate change could be exacerbating lead risks, and researchers have found that childhood lead poisoning levels spike during hotter periods.

Perry now lives in Oak Forest, one of Chicago’s southern suburbs, but she also owns the home her mother lives in, on Chicago’s South Side. That home has a lead service line, Perry said, and she doesn’t know when it will be replaced.

The city has “a responsibility to the residents in the city of Chicago to protect them at all costs,” Perry said. “There’s no price that’s too high to pay for safe drinking water.”

Chicago’s plan is based on a 2021 state law requiring that water systems with 100,000 or more lead service lines — which includes Chicago — replace all of them within 50 years from 2027.

At the time of its passage, this state law was stronger than the federal Lead and Copper Rule Revisions of 2021, which did not require replacement in most cases.

Experts and advocates criticized and even sued the EPA over that rule — enacted by the Trump administration in the final days of the president’s first term — saying it weakened existing efforts to achieve safe drinking water nationwide.

Near the end of President Joe Biden’s term, the EPA finalized the current rule. Most systems across the country must replace all their lead service lines before 2038, with deferral allowances for places with large proportions of lead service lines — like Chicago, which would likely get until mid-2049 to finish.

The EPA estimated that each year this rule will prevent up to 900,000 cases of low birth weight and 1,500 cases of premature death from heart disease. Many advocates praised the rule, while others noted that two more decades of lead pipes still pose significant health risks in Chicago.

But according to the document the city submitted to the state, Chicago’s plan hasn’t yet caught up to the newer federal law. The plan acknowledges the faster federal timeline but notes that Chicago isn’t abiding by that yet.

The city, its plan states, will comply “if the regulations go into effect.”

Nationally, the regulation is already in effect, Earthjustice’s Lieberman-Klein said, and the EPA does not need to release any additional documents to make that true.

But what city officials might be thinking, she said, is that given the continued rollbacks of many environmental and health regulations by President Donald Trump’s EPA, this requirement might eventually be wiped off the books.

“It’s possible Chicago is just looking at what this administration has been generally saying about rules promulgated by the previous administration, and it’s saying, ‘We’d like to wait and see what they say about this rule,’” Lieberman-Klein said.

Some congressional Republicans tried to revoke the lead pipe replacement rule legislatively, but they missed the deadline to do so.

Last year, the American Water Works Association — a water industry organization — challenged the rule in court, alleging that its requirements are not feasible. Environmental groups stepped in to defend the rule, but it remains to be seen whether the EPA will do likewise. The agency declined to comment on the pending litigation.

Chicago’s water department cited the lawsuit as one of its reasons for submitting a plan that doesn’t account for the 20-year replacement timeline. But the rule isn’t on pause, Earthjustice’s Lieberman-Klein clarified.

“The litigation does not stay the rule or change its effective date,” she said. “It still went into effect at the end of October and nothing about the compliance dates have changed.”

Over the past few years, Chicago officials say each service line replacement has averaged about $35,000, although they plan to lower these costs by more frequently replacing the service lines for full blocks at a time. This is much higher than national estimates, which range from about $4,700 to $12,000 per line.

Regardless, it will be no easy feat for Chicago to piece together the funds to finish the job quickly, and big proposed cuts to federal funding would make a challenging task even harder.

The Trump administration’s proposal for the EPA next fiscal year would cut the agency’s budget by more than half. Part of that plan: slashing almost all the money for the low-interest loan program that states rely on to update water pipes.

Trump’s budget proposal says “the states should be responsible for funding their own water infrastructure projects.” Chicago’s plan notes that $2 million of expected funding for a program focused on replacing lead service lines in daycares serving low-income communities was lost this year in the blanket elimination of congressional earmarks.

Megan Glover, co-founder and former CEO of 120Water, an Indiana-based company that runs a digital platform to help water systems manage lead replacement programs, wasn’t surprised by the news. Federal funding is a concern for her company’s customers across the country, she said.

“All grants and earmarks, we’re kind of starting from a ground-zero standpoint,” Glover said. “All of that is kind of up for grabs at this point with the new administration.”

Anna-Lisa Gonzales Castle is director of water policy at Elevate, a Chicago-based nonprofit focused on water and energy affordability that is also involved with local lead service line replacement programming. She said that ramping up replacement speeds will be a challenge, but homeowners shouldn’t be left on the hook for something that wasn’t their fault.

“We want to see the city move swiftly, and we want to see the federal government and the state bring resources to bear on this too,” she said. “It’s gonna be an all-hands-on-deck approach.”

Explore which areas are most at risk from lead pipes. Sign up to be notified when we release more reporting on Chicago’s lead service lines and an interactive map.

Source link

Keerti Gopal grist.org