Beatriz Salazar was sifting through her usual pile of mail this spring when an envelope from the city of Chicago caught her eye. Inside, she found a letter warning her — in 10 different languages — that her drinking water was delivered to her tap through a toxic lead pipe.

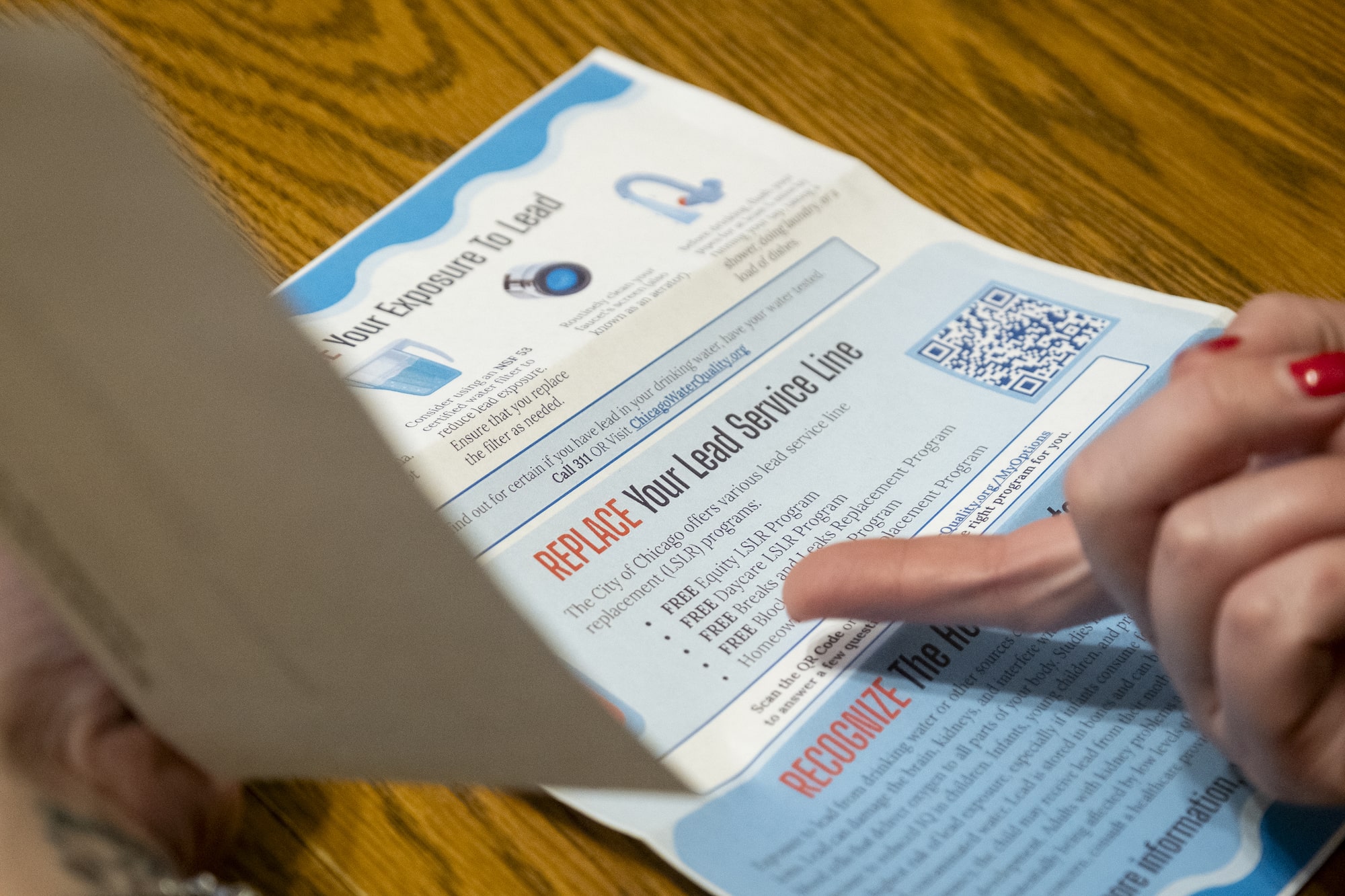

With it, the city included tips to reduce exposure, links to city programs to help replace the pipe, and a full-page diagram showing how the lead can flake or dissolve into tap water from a service line or other plumbing infrastructure and cause serious health harm, including brain and kidney damage.

“Lead?” Salazar remembered thinking. “We’ve been drinking lead for how long?”

Salazar, a housing counselor, lifelong resident of the city’s Southeast Side and mother of two, immediately called friends and family. Her mother-in-law, who lives around the corner, had received the same letter. So, too, had one of her clients. But others, including her mother, 74-year-old Salome Fabela, fewer than 10 blocks away, hadn’t seen or heard anything about it.

Keerti Gopal / Inside Climate News

A federal drinking water rule required Chicago officials to warn approximately 900,000 renters, homeowners, and landlords before November 16, 2024, that their drinking water is at risk of lead contamination. Their properties were built before 1986, when the city required the installation of lead service lines. Lead pipes were banned nationwide that year.

But as of early July, Chicago had only notified 7 percent of the people on its list that their water may be dangerously contaminated.

Fabela’s home, according to city records, is connected to a service line containing lead, so she should have received a letter. But she is among the vast majority of people who — eight months past the deadline — still have not been warned. The federal law requires water systems to warn residents on a yearly basis until all of its lead pipes are replaced.

Megan Vidis, spokesperson for the Department of Water Management, estimated that about 3,000 letters are mailed out every week, adding up to about $8,500 in monthly costs.

Advocates worry that the city’s delayed warnings could keep already vulnerable communities in the dark about the state of their drinking water and what they can do about it. A study published last year found two-thirds of Chicago children under 6 years old live in homes with tap water containing detectable levels of lead.

Vidis said DWM has asked the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency for more time to make its notifications, but they haven’t received an extension thus far. She added that the state is aware of Chicago’s delay and estimated that the city would not complete its first round of mailed notifications until 2027, but that it will notify residents electronically by the end of this year.

IEPA said water systems that did not certify completion of the requirement by July 1 will receive a reporting violation that they will have to make public.

Lead pipes are a serious health hazard, and millions are still in use across the country in older homes and buildings. No other city in the nation is so reliant on the dangerous metal as Chicago, where around 412,000 out of about 490,000 service lines are at least partly made of lead, or may be contaminated with it. And the city doesn’t plan to finish replacing them for another five decades — 30 years later than required by the federal government.

Climate change could amplify the health risks of lead pipes because soaring temperatures can increase the amount of lead dissolving into and contaminating drinking water. Service lines, which bring water from the street into homes and buildings, are just one of many plumbing fixtures — along with faucets, valves and internal plumbing — that can add lead to drinking water.

All of that makes timely notifications even more important.

This is the first time water utilities have been required to notify the public they might be getting water through a lead pipe, according to Elin Betanzo, founder of Safe Water Engineering. Betanzo was instrumental in uncovering the water crisis in Flint, Michigan — which celebrated the replacement of a majority of its lead service lines earlier this month.

Chicago has provided other resources to let residents know that houses built before 1986 are likely to have a lead service line, including an online lookup tool that shows the material sourcing water to a specific address. The city also encourages residents to test their water by calling 311 and signing up for a free lead test kit. But the program was unable to complete any tests in May while it was undergoing maintenance, and it’s currently backlogged. Some residents have been waiting months, or even years, to receive results.

Gina Ramirez, director of Midwest environmental health for the Natural Resources Defense Council, said her mother completed a lead test in 2022 and never received results, although her service line was replaced through a city program geared toward lower-income residents in 2023.

Of the 10 cities with the most lead service lines in the country, only Chicago has confirmed that it has not yet finished mailing all its notices. By the end of last November, about 200,000 notices had gone out in Cleveland and Detroit, more than 100,000 in Milwaukee, more than 85,000 in Denver and St. Louis, more than 75,000 in Indianapolis, nearly 70,000 in Buffalo, and more than 55,000 in Minneapolis, according to the cities’ respective water departments and utilities. New York City did not respond to multiple inquiries.

In Chicago, only about 62,000 of the 900,000 notices that were due in November had gone out by early July. In some cases, they pointed residents to broken links.

While Chicago is struggling to mail 3,000 notices a week, Milwaukee sent over 100,000 in a single day. And Detroit has already sent 124,000 this year after its 200,000 last year.

“People are not getting the information they need to protect themselves,” Betanzo said of Chicago’s pace. “It’s information they should have had a long time ago, and we’re continuing to delay that? That’s not OK.”

Keerti Gopal / Inside Climate News

Chicago has a big job ahead, replacing hundreds of thousands of lines that are partially owned by private citizens, and it has to get permission from homeowners to replace their portion of the line. The city has said in its service line replacement plan that notifying homeowners of the problem and why it should matter to them is an important step in building buy-in for replacement.

Suzanne Novak, a senior attorney working on safe drinking water issues for the nonprofit Earthjustice, said she thinks Chicago’s delay means city officials aren’t taking their responsibilities to the public seriously.

“They are brazenly violating the law,” Novak said. “We not only need them to step up and catch up really quickly, but we also need the state of Illinois and EPA to use their powers to hold them accountable for this blatant lack of compliance with the law.”

The EPA also requires water systems to send out three types of notifications to residents: one if their service line is confirmed to be made of lead; another if it’s galvanized steel, which contains lead; and a third if the material of their service line is unknown. So far, Chicago has only started sending letters to homes with confirmed lead service lines.

Chicago officials say they are also prioritizing notifications by neighborhood and type of home. So far, the city has notified homes within 15 wards, mostly in lower-income areas on the city’s South, West, and Northwest sides. The city has begun by sending letters to single-family homes, which officials say are more likely to experience higher lead contamination due to less water usage and, subsequently, more water stagnation in the pipes.

But advocates and residents say the notification letters haven’t reached every affected home in these categories. Salazar and her mother both live in the 10th ward, one of the city’s priority areas, and Fabela lives in a single-family home.

Vidis, the spokesperson for the city’s Department of Water Management, said Fabela had not yet received a letter because city records showed she has a galvanized steel pipe. Vidis said Fabela’s notice would go out this year but did not specify when.

“I just think they should have done something to inform us faster,” Salazar said. “I think they’ve known this, and they’re just now informing us.”

Vanessa Bly, co-founder of Southeast Side neighborhood advocacy group Bridges//Puentes: Justice Collective of the Southeast, has been working since 2022 to raise awareness about the dangers of lead in drinking water. Last year, Bly began working with a Northwestern University laboratory that is developing rapid, at-home lead tests.

Bly has been troubleshooting the experimental test kits with homeowners like Salazar and Fabela on the Southeast Side. The predominantly Black and Latino community experiences disproportionate pollution and health harms linked to toxic exposures, including higher rates of chronic disease and lower life expectancy. Decades of disinvestment have also bred distrust with the city.

Coming soon: More reporting on Chicago’s lead service lines, plus an interactive map to explore which areas are most at risk. Sign up to be notified when these stories and tools are available.

Have you been affected by lead pipes or lead exposure in Chicago? Tell us what happened.

Over and over, Bly has found that many of her participants still haven’t received lead notifications from the city. She worries about residents drinking their tap water with no idea it could be unsafe.

“Is it so hard to have a commercial campaign to talk about it?” Bly asked.

Some residents have long been suspicious about their water quality, even if they didn’t know it might contain lead. Salazar and her kids drink bottled water at home and keep a filter in the refrigerator, she said. Her mother, Fabela, has filtered her water for almost 25 years, first through a filter attached to her tap, and then through a handheld pitcher.

At her mother’s kitchen table, Salazar looked over the city’s options for lead service line replacement. She doesn’t qualify for Chicago’s equity program, which replaces lines for free for homeowners whose household income is below 80 percent of the area median income. The city is raising money to cover costs for more homeowners, but it hasn’t told Salazar when it might get to her line. And she doesn’t have $30,000 to pay for her own immediate replacement.

For now, she said, continuing to filter her water is probably the most realistic option. But she thinks the city should have told her and her family about the risk sooner.

“How long have they known?” Salazar asked. “And why did it take them so long to inform us?”

Editor’s note: The Natural Resources Defense Council and Earthjustice are advertisers with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

Source link

Juanpablo Ramirez-Franco grist.org