As Gina Ramirez buckled her 11-year-old son into her car last month for their daily drive to school, she handed him a plastic water bottle.

“I would love to be able to have him put a cup under the tap if he was thirsty,” Ramirez said.

She can’t.

Ramirez lives in a home on Chicago’s Southeast Side that’s serviced by a lead water pipe, a toxic relic found in most old homes in the city and many across the country. Exposure to lead can cause serious health harms, including neurological, kidney, and reproductive issues. Infants and young children are particularly susceptible.

A longtime activist, Ramirez knows that she and many of her neighbors have lead pipes in a community where residents are already overburdened by toxic pollutants in the air and soil. She also knows Chicago is lagging behind federal requirements to warn residents about their presence, and that the city isn’t planning to finish replacing them until 2076, three decades past a federal deadline.

Keerti Gopal / Inside Climate News

Each day, Ramirez makes the hour-long drive to her son’s year-round therapeutic school in Avondale on the Northwest Side, then heads to her office downtown. As the landscape around her changes from smokestacks and warehouses to shops and restaurants, she suspects lead pipes are another danger that disproportionately impacts her neighborhood and the families who live there.

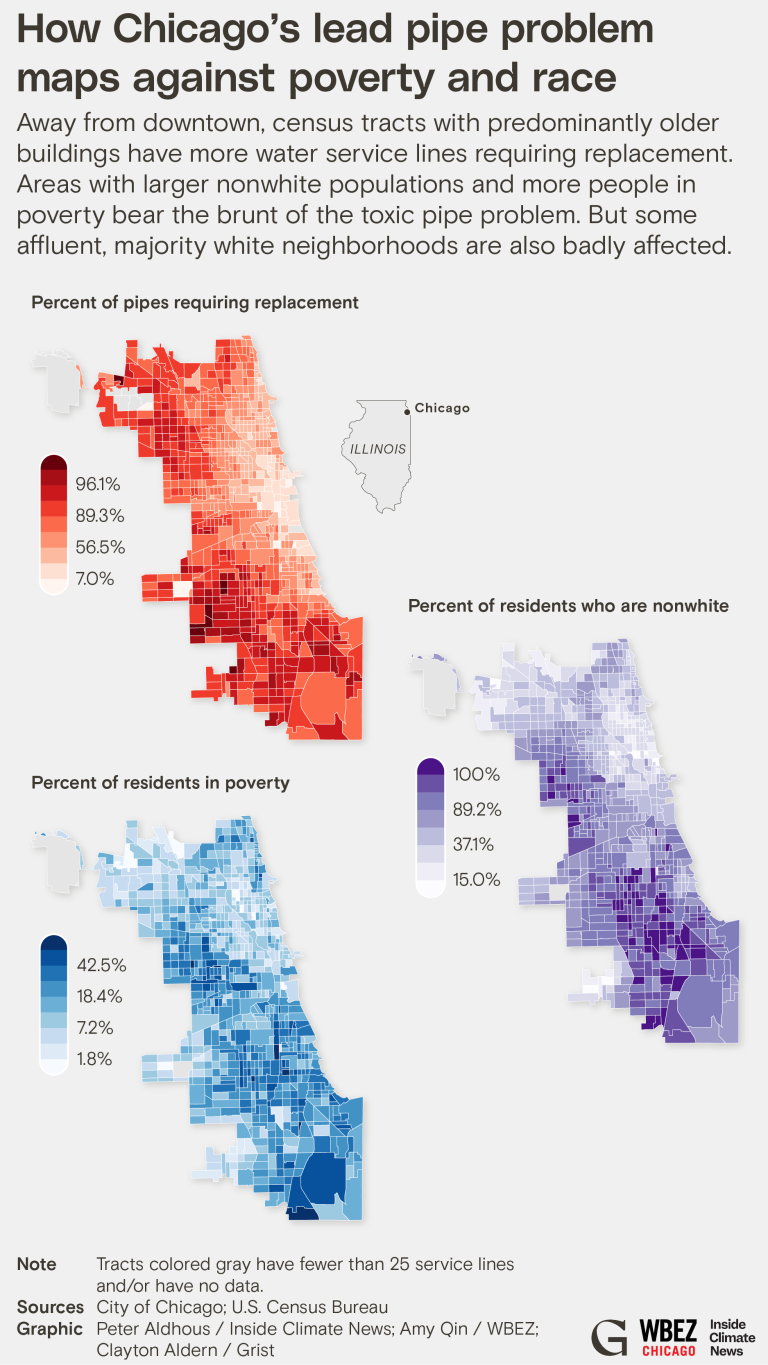

Chicago has the highest number of lead water service lines in the nation, with an estimated 412,000 of about 491,000 lines at least partly made of lead or contaminated with the dangerous metal. For the first time, Grist, Inside Climate News, and WBEZ have analyzed city data obtained through a public records request that allows Chicago’s residents to see where the problem is most acute — and how it intersects with poverty and race.

The analysis — which includes an interactive map that allows residents to search their address for information on their water lines — found that the toxic pipes plague residents throughout the city, across lines of race and class.

But majority Black and Latino neighborhoods — including Ramirez’s own — bear the biggest burden.

Use this map to view confirmed and suspected lead service lines across Chicago, alongside distributions of race and poverty.

Service lines are the underground pipes that connect the city’s water main to your home’s internal plumbing. When these and other plumbing materials contain lead, tiny pieces of the toxic metal can dissolve or flake off into the water coming out of your tap.

To use this interactive tool, enter a Chicago address to see the status of its service line material. The map is based on the Department of Water Management’s service line inventory, submitted to the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency on April 14, 2025, and will not reflect replacements after that date. Many household addresses are missing from this inventory list, because in many cases a single service line can serve multiple households. Some service lines are also logged in the inventory by the nearest intersection, rather than a numbered street address. If your address does not appear, the tool will allow you to view nearby lines, which may include those serving your building.

For available addresses, the search tool will reveal the material, if known, of the three components of the line or lines serving that location: the gooseneck, a flexible curved pipe that connects to the water main; the public-side line, owned by the city, running under the sidewalk; and the private-side line, running into the building to internal plumbing. DWM classifies entire service lines based on its knowledge about these components, putting them into one of four categories:

- Lead: At least one component of the service line is known to be made of lead.

- Suspected Lead: The composition of the service line is marked unknown in the city’s inventory, but is suspected to contain lead components, usually based on the building’s age.

- Galvanized Requiring Replacement: No components of the service line are known to be made from lead, but at least one is composed of galvanized steel, which can become contaminated with lead from upstream pipes.

- Non-Lead: None of the components of the line are made from or may be contaminated with lead.

If your address is known or suspected to have a lead service line, you can request a free testing kit from the city to confirm your eligibility for some city programs that cover replacement costs.

Learn more about how we created this map and how to use it.

In majority-Latino census tracts, areas that in Chicago average around 1,500 households each, 92 percent of service lines require replacement. In majority-Black tracts, the figure is 89 percent. That compares to 74 percent of service lines in majority-white census tracts and 65 percent in the city’s nine majority-Asian tracts in and around Chinatown.

Among the worst affected are neighborhoods on the South and West sides, where residents grapple with other environmental health concerns due to the concentration of nearby industrial facilities, expressways, and freight trucks spewing air pollution. Communities there suffer from high rates of chronic disease and low life expectancy.

The nine community areas with the highest percentage of pipes requiring replacement are all on the South Side. The 10th is Belmont Cragin, a majority-Latino neighborhood on the Northwest Side.

Through its subsidized replacement program for low-income residents, the city has mostly replaced service lines on the South and West sides, said Megan Vidis, spokesperson for the Department of Water Management. Other local programs have replaced lines throughout Chicago.

“There is nothing new in this analysis,” Vidis wrote in an email about the newsrooms’ map. “For decades, we have been saying that residents who live in a single-family house or two- flat built before 1986 should assume that they have a lead service line.”

Though the city has mapped lead service lines and prioritizations for replacements in the past, this analysis is the first interactive tool that allows residents to view their own service lines in the context of their neighborhood and city alongside data on poverty and race, with the most up-to-date inventory available.

Rachel Havrelock, a University of Illinois Chicago professor who directs research on water resources and equity, said exposure to lead intensifies health risks for low-income and minority communities already living near other hazards like industrial air pollution.

“It really speaks to this whole question of cumulative impacts,” Havrelock said. “How much can the human body withstand?”

In Ramirez’s Southeast Side neighborhood, 94 percent of the water service lines are confirmed or suspected to contain lead. In Avondale, where Ramirez’s son attends school, that number is slightly below the citywide average of 84 percent. Downtown at her office in the Loop, it’s just 16 percent.

“I see the tale of two cities every day taking my son to school, and I get mad,” said Ramirez, an environmental health director at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Keerti Gopal / Inside Climate News

Factors such as barriers to internet access, water shutoffs, poor plumbing infrastructure, and a lack of disposable income to deal with those issues can all exacerbate the impact of a community’s lead service lines on its residents. So can having many young, elderly, immunocompromised, or pregnant residents.

Lead exposure can lead to premature birth, low birth weight, developmental delays, learning difficulties, and permanent behavioral and intellectual challenges. In high quantities, lead can even cause seizures, comas, or death. Adults aren’t immune and can develop high blood pressure, joint and muscle pain, memory issues, and mood disorders.

Chicago has more than a million homes and apartments, most of which are connected to service lines that likely contain lead and should be replaced.

There is no safe level of lead exposure, experts emphasize.

“We all know that we have the most lead service lines in the country,” Ramirez said. “But we need to look at the impact and the severity. Folks on the Southeast Side of Chicago and the South and West sides of Chicago are feeling the impacts and are feeling the severity of lead much greater than folks on the North Side.”

Lead pipes were required by Chicago municipal code until a national ban in 1986. Relatively few lines have been replaced since, so most older buildings across the city are still serviced by the toxic metal. Lead pipes are the least prevalent downtown, where most buildings went up after the lead pipe ban or are too large to accommodate a lead line.

This means even relatively affluent, majority-white neighborhoods in the far northwest corner of the city have a significant toxic pipe problem. In Forest Glen, a community with the second-highest median household income in the city, 91 percent of service lines require replacement.

Colton Wyatt and his wife, Rebecca Weaver, recently moved to a home with a lead service line in Lincoln Square, a majority-white neighborhood on the North Side with a median household income about $20,000 above the citywide average. Before buying the home, Wyatt said they did an “obsessive amount of research” and were drawn to the neighborhood by its great schools, burgeoning restaurant scene, walkable park, tree-lined streets, and neighbors with young kids.

“The idea is that we have so much space, so we’ll eventually be able to turn it into a three-generation home for our parents, ourselves, and our imaginary unborn children,” Wyatt said.

He grew up in Michigan and later learned about the dangers of lead from the Flint water crisis, so inspecting the home’s plumbing was on his mind. And sure enough, he found their otherwise nearly perfect home has a lead service line and all kinds of internal lead pipes.

After buying their house in Lincoln Square, Colton Wyatt and his wife discovered that it had lead pipes, including a lead service line. Anthony Vazquez / Sun-Times

A plumber estimated it would cost about $26,000 to replace the private side of the home’s service line. Swapping out his internal lead plumbing would cost thousands more. At this point, having just purchased the home, the couple doesn’t have the money to replace their service line. For now, they’ll keep testing and filtering their water.

Earlier this summer, Wyatt submitted a sample of his water to the city’s free testing program. Last week, the city notified him that the lead level reached 16 parts per billion. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says the goal should be zero. Wyatt worries about bringing children into the home and about renters on his block who might not be able to renovate their plumbing.

“I am pretty disappointed that this is a program that Chicago hasn’t really invested in,” Wyatt said. “I know they could do it a lot faster.”

In Wyatt’s neighborhood, 77 percent of service lines require replacement, which is lower than the citywide average, but still a significant majority of addresses.

The data shows that most city neighborhoods have lead in the majority of their service lines. Citywide, only five community areas have a share less than 50 percent.

A 2024 study by researchers at Johns Hopkins and Stanford universities found nearly 70 percent of Chicago children under 6 live in homes with tap water that contains detectable levels of lead.

About 4 percent of Chicago children aged 1 to 3 who were tested in 2024 had a lead level above the state’s threshold for an elevated result, according to the city’s health department, slightly higher than the share in 2023.

Both years, only half the city’s kids aged 1 to 3 were tested. The 2024 study found Black and Latino children in Chicago were less likely to receive testing while also being more likely to live in a home with lead-contaminated water.

Statewide, racial inequities in lead exposure are even clearer. The Metropolitan Planning Council, a nonprofit addressing regional infrastructure issues, analyzed data from the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency in 2020. It found nearly two-thirds of Black and Latino residents live in municipalities that contain 94 percent of the state’s known lead service lines, compared with less than one-third of white Illinoisans.

The city of Chicago has repeatedly said its drinking water is in compliance with federal guidelines and that lead exposure mainly comes from other sources, like paint and soil. But experts say federal requirements for water testing and its lead thresholds aren’t adequate to protect public safety.

“The regulations about lead in drinking water that utilities need to comply with now are abhorrent,” said Suzanne Novak, a senior attorney with Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law organization. “There is no safe level of lead. Any level of lead presents a risk of neurological, irreversible harm.”

Anthony Vazquez / Sun-Times

The city began a coordinated replacement effort for lead service lines in 2019 and has said it is prioritizing work in high-risk locations, like parks, childcare facilities, and hospitals — and in disadvantaged census tracts.

Of the 2,679 service lines the city calls high-risk, 675 still required replacement as of April, a markedly better rate than the rest of Chicago.

But even with this work, Chicago is lagging far behind on replacements citywide, blaming insufficient funding. Dwindling federal dollars could worsen the problem. The Trump administration proposed massive cuts to water infrastructure programs for the fiscal year beginning in October.

Advocates say the burden to fund this kind of infrastructure overhaul shouldn’t fall on a single department or revenue source: It will take action from city council, the mayor’s office, and state officials, especially as federal funding becomes increasingly unreliable.

“We need to kind of push this up, and get the governor involved,” said Brenda Santoyo, the water justice program manager at the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization. “This should be a priority because of the amount of people who are being impacted by this.”

Santoyo’s organization has been working to raise awareness of the lead pipe issue for years — engaging in community outreach, handing out free filters, and educating residents on how to apply for city programs. The organization works in a predominantly Latino community on the Southwest Side with a history of chronic environmental health burdens, and Santoyo said she sees lead service line replacement as a possible avenue to fight health disparities and counteract legacies of segregation and disinvestment.

The Child Opportunity Index, which looks at neighborhood resources and conditions that contribute to children’s healthy development, also shows stark inequities across the city. Many of the neighborhoods with lower scores for childhood opportunity align with where our analysis shows a high concentration of lead service lines.

Ramirez views lead as a compounding factor that puts communities and families like hers at a disadvantage.

She has high blood pressure. Her mother has suffered from severe asthma for years, and now has lupus and diabetes.

“I’ve seen the devastating toll this neighborhood has had on her health, and just our mental health too,” Ramirez said.

Keerti Gopal / Inside Climate News

Like many South Side residents, Ramirez grew up drinking bottled water in a home with a lead service line. She remembers watching her father carry heavy cases of water into the house and watching her mother pour bottled water into pots to make soup. After a long application and approval process, her parents finally had their line replaced two years ago through the city’s subsidized replacement program for low-income homeowners.

Ramirez doesn’t qualify for that program, but between therapeutic school tuition and the costs of raising a family, she can’t afford to cover her own replacement.

For now, Ramirez is stuck filtering and purchasing water for herself, her husband, and her two kids — including a 1-year-old, whose formula bottles she washes using jugs of distilled water. It makes her angry that the city is addressing this problem so slowly that it won’t be done for half a century.

“My infant son will be mid-life,” Ramirez said. “I just think that it’s completely unacceptable.”

Ramirez’s 1-year-old son, Miles, has never drank their home’s tap water, she said. Instead, she purchased gallons of purified water to mix formula for him. But it makes her angry that the city doesn’t plan to be rid of toxic lead service lines until he’s middle-aged. Keerti Gopal / Inside Climate News

Ramirez’s neighborhood is cut off from the rest of the city by the Calumet River and has long been choked by industry. Each day, as she drives north onto the Chicago Skyway Toll Bridge, she sees a metal processing warehouse and a cement plant that have both been flagged by the EPA for toxic emissions. All of that disappears within the hour it takes to get to her son’s school.

Ramirez drives her 11-year-old, Evan, to school year-round on the North Side because no schools in her neighborhood meet his needs: Evan has autism spectrum disorder and has thrived at the therapeutic school in Avondale. For Ramirez, the fact that her neighborhood doesn’t have the services he needs is another illustration of the disinvestment that haunts her community.

“The cards are already stacked against him … and on top of it we live in this beautiful city, and they’re dumping on him,” Ramirez said. “I want him to have the same shot at life as other kids on the North Side.”

Coming soon: We will continue investigating Chicago’s lead pipe crisis. Sign up to be notified when we publish more reporting.

Have you been affected by lead pipes or lead exposure in Chicago? Tell us what happened.

Source link

Keerti Gopal grist.org