The COP30 climate summit in Belém, Brazil, has come to an end. After two busy weeks of presentations, discussions and negotiations between global leaders, researchers, public citizens, nonprofit organizations and activists, the question of whether the first COP to take place in the Amazon delivered on its climate promises depends on who you ask.

The proceedings concluded with an agreement to triple adaptation funding for developing nations and the clean energy transition by 2035, and to reach the $1.3 trillion annual spending goal for climate action. This year’s conference also made headlines for reasons beyond the negotiations—including Indigenous groups who blocked the entrance to COP to demand better protections for the Amazon, and a fire that broke out inside the venue.

Several Columbia and Climate School representatives were in Brazil, hosting panels, giving talks and fostering important connections. Now that they’re back, we asked them to reflect on their time at COP: What were the biggest achievements and roadblocks?

You can read about additional COP30 coverage and events here.

Alexis Abramson, dean of the Columbia Climate School

What were your main takeaways and most memorable moments from the conference?

COP30 came at a pivotal moment where conversations are shifting from ambitious commitments to the concrete implementation of climate solutions. Around the world, the effects of climate change are no longer distant projections. They are unfolding in real time. Communities are experiencing severe flooding, extreme heat, agricultural disruption and displacement, with emerging economies bearing the most acute impacts. And financing adaptation isn’t charity; it’s risk management for communities and economies that underpin national and global stability. COP30 highlighted the urgent need to accelerate climate adaptation and expand effective financing mechanisms to support communities.

For me, one of the most meaningful moments of the conference was participating in a panel the Climate School co-hosted with the UNFCCC, “Financing Climate Adaptation: Old Challenges, Emerging Threats, Novel Solutions.” The discussion reinforced that adaptation is dramatically underfunded relative to the need. Climate finance, particularly adaptation finance, remains central to progress that will require multisector partnerships. The message was clear: implementation must accelerate, and adaptation cannot wait.

The conference also highlighted the need for diverse voices and locally informed solutions to ensure commitments translate into tangible impact on the ground. The breadth of participants—from frontline community leaders to industry innovators—was a powerful reminder that durable solutions emerge only when those closest to the challenges help shape the path forward.

What was achieved at COP on a personal or broader scale?

Attending my first COP was an eye-opening experience. It was inspiring to connect with leaders, negotiators and practitioners from around the world and witness how research, policy and practice come together to address urgent climate challenges. It highlighted the central role that institutions like the Columbia Climate School play in bridging knowledge and implementation, shaping both policy and practice in real time. The Climate School hosted several events during COP30, spanning the topics of careers in climate, financing climate adaptation, and the role of higher education in facilitating community co-creation.

It was exciting to witness the launch of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage’s call for funding requests, with dignitaries from multiple countries and international organizations present. Established at COP27, the fund is a tangible mechanism delivering support to communities already facing severe climate impacts. Seeing it in action made the urgency of moving from pledges to real solutions unmistakable.

Any missed opportunities?

COP30 made important progress, but key gaps remain. Adaptation funding is still insufficient to meet the urgent needs of communities already facing severe climate impacts, and implementation is not keeping pace with the growing crisis.

Making the case for climate adaptation needs to be made more convincingly: we can no longer separate climate action from the stability of our communities, economies, and infrastructure. Even as we accelerate decarbonization, the impacts already locked-in demand smart, timely investments to protect people, reduce mounting costs, and preserve development gains. Adaptation finance is both cost-effective and profoundly equitable—every dollar spent today avoids far larger losses tomorrow and strengthens the resilience of communities with the fewest resources. Ultimately, financing adaptation isn’t optional; it’s a strategic investment in safety, stability and shared prosperity in a warming world.

Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at the Columbia Climate School

What were your main takeaways and most memorable moments from the conference?

One takeaway is that while the negotiators work toward implementation frameworks for climate adaptation and other goals, the partners in the Blue Zone and Green Zone were busy announcing new initiatives and sharing best practices for implementation. New initiatives included novel financing vehicles for climate adaptation from development banks, to highlighting working with communities and indigenous communities to co-develop climate adaptation strategies. While a lot of attention has been paid to the negotiations, the notion of this as the “implementation COP” was clearly visible throughout.

What was achieved at COP on a personal or broader scale?

Our work at the Climate School was heavily featured across dozens of events and panels. I moderated four panels focused on topics that include: educating current and future leaders in climate finance; developing new paradigms for supporting climate adaptation; our work with communities to ensure climate solutions have strong community-led partnerships; and how we work with implementing agencies to ensure our research and education extends into impact. But these are just a small fraction of the breadth of topics represented by our faculty, researchers, students and affiliates at COP this year.

Any missed opportunities?

Yes and no. While the U.S. federal government was not represented in the negotiations at COP30, the U.S. presence was felt. Universities like Columbia provided leadership and advice in areas of climate impacts, mitigation, adaptation, and equitable integration of the most vulnerable. Sub-national representation from U.S. states and cities was also very visible. I also had the opportunity to speak to some past negotiators who were there to advise representatives like governors and mayors, as well as to provide mentorship to negotiators from other countries who may lack the resources of a full diplomatic corps like in the U.S. and other wealthy countries. Even with opportunities missed, the work continues, and the U.S. continues to be an important voice in the conversations with the Columbia Climate School continuing to be a leading voice in the global community.

Dong Guo, professor of practice in sustainability management at Columbia’s School of Professional Studies, and the associate director of the Research Program on Sustainability Policy and Management at the Columbia Climate School

What were your main takeaways and most memorable moments from the conference?

One of the takeaways was the need to balance rainforest protection with sustainable economic opportunities for the people living there. From the people I met in Belém, there is a clear recognition that we cannot simply protect the rainforest by fencing it off; we must develop sustainable bio-economies that provide livelihoods for the over 50 million people living in the Amazon region. The fate of the forest is linked to the well-being of its urban and rural communities. One of the memorable moments was seeing lots of Indigenous peoples at the COP, both inside the conference and outside protesting.

What was achieved at COP on a personal or broader scale?

Personally, we successfully launched our urban sustainability report for 2025, which was extensively covered by dozens of media outlets from across the world. We also met with Imazon, a well-known research institute based in Belém that uses advanced geospatial monitoring to track deforestation and promote sustainable development. Our goal is to collaborate on a future project adapting the framework we developed for Chinese cities, and using Imazon’s extensive dataset to help build sustainable, low-deforestation bio-economies for the communities within the Amazon. On a broader scale, I feel the conference brought awareness that Indigenous people are essential guardians of the forest. However, we have to be aware that less than one percent of major international climate funding for the Amazon reaches Indigenous and local communities. COP30 launched the Tropical Forests Forever facility with modestly higher pledges, but importantly, there was a strengthened commitment to direct at least 20 percent of such finance to Indigenous and local communities.

Any missed opportunities?

I was able to meet with some local people, researchers and government officials, but I was at the conference only for around half a day, which gave me no chance to really engage with more people, and listen in and learn the diverse perspectives at the conference.

Sheila Foster, professor of climate at the Columbia Climate School and an affiliated faculty member at Columbia Law School

What were your main takeaways and most memorable moments from the conference?

I returned from COP30 in Belém both heartened and disappointed by the progress toward a more climate-just world. Brazil delivered what Indigenous leaders themselves and observers called “the most inclusive COP” in years. In important ways, it was. Indigenous peoples weren’t just present in the hallways and side events; their voices, their land tenure systems, and their rights were seriously discussed as climate solutions at the negotiating table. This COP felt different in that regard. The question I kept hearing, however, was: Is this enough? Will this carry through to future COPs when the presidency changes hands?

COP30 made real strides toward operationalizing Paris Agreement commitments that directly address climate justice. The newly adopted Just Transition Mechanism explicitly emphasizes the importance of meaningful participation by Indigenous peoples, Afro-descendants, women, youth, workers affected by transitions, and informal workers in discussions and negotiations. The renewed Forest and Land Tenure Pledge, the Intergovernmental Land Tenure Commitment covering 160 million hectares, and the launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility with its 20 percent financing target for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities represent real progress in recognizing that those who have protected forests for generations must be resourced to continue doing so.

The policy architecture emerging from Belém includes other significant pieces: 59 adaptation indicators spanning water, food, health, ecosystems, infrastructure and livelihoods; a Gender Action Plan that advances gender-responsive budgeting and promotes leadership of Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and rural women; and commitments to triple adaptation finance by 2035.

“We have adaptation indicators now, but what good are 59 ways to measure suffering if there’s no mechanism to compel those responsible to act?”

– Sheila Foster

What was achieved at COP on a personal or broader scale?

On paper, COP30 built important scaffolding for climate justice. However, there is still a big accountability gap ten years after the signing of the Paris Agreement. This was at the center of conversations I had on two panels I participated in.

I was part of panel sessions that assessed where we are ten years after the signing of the Paris Agreement. The Global Stocktake, meant to hold countries accountable for their commitments, requires transparency but lacks the metrics and binding goals needed to hold the largest current and historical emitters responsible for impacts hitting the Global South and Small Island Developing States with devastating intensity. Recent reminders of these impacts include Hurricane Melissa in Jamaica, Cuba and Haiti, back-to-back typhoons in the Philippines, and catastrophic floods in Sri Lanka and Indonesia. We have adaptation indicators now—voluntary and non-prescriptive—but what good are 59 ways to measure suffering if there’s no mechanism to compel those responsible to act?

The financing that was supposed to materialize hasn’t, really. Forest funding was announced at COP30, but veterans of these negotiations know to be skeptical. How much money will actually flow, on what timeline, and with what strings attached? Loss and damage funding—the issue that dominated COP27 and 28—is moving forward slowly but remains largely aspirational. Debt-free financing and technology transfer, the kind that would enable genuine adaptation and just transitions, continue to be deferred.

Coming out of COP30, we have more of the right language, more representation and more frameworks. That matters. The students I teach in my Climate Justice courses—the next generation of lawyers, policymakers and activists—need to know that movements build slowly and that progress comes in layers. But they also need to know the hard truth: procedural justice without material justice is incomplete. Architecture without accountability goes nowhere.

Any missed opportunities?

COP30 moved me. It also disappointed me. What is clear is that the work continues: to hold the line on accountability, to ensure that inclusion translates to decision-making power, and to demand that promises become resources that reach the communities that need them most.

Page Fortna, chair and Harold Brown Professor of U.S. Foreign and Security Policy in the department of political science at Columbia University

What were your main takeaways and most memorable moments from the conference?

COP is a sort of surreal juxtaposition, on the one hand, of the official negotiations, in which petrostates like Russia and Saudi Arabia (and the U.S. not even bothering to show up) blocked progress on a roadmap for the transition away from fossil fuels (unsurprising given their interests, but still dismaying for the planet), and on the other, the panels and side events in the Blue Zone, in which huge amounts of information on climate change and decarbonization were shared, and the protests like the “fossil of the day” award given to the worst actors in the official negotiations.

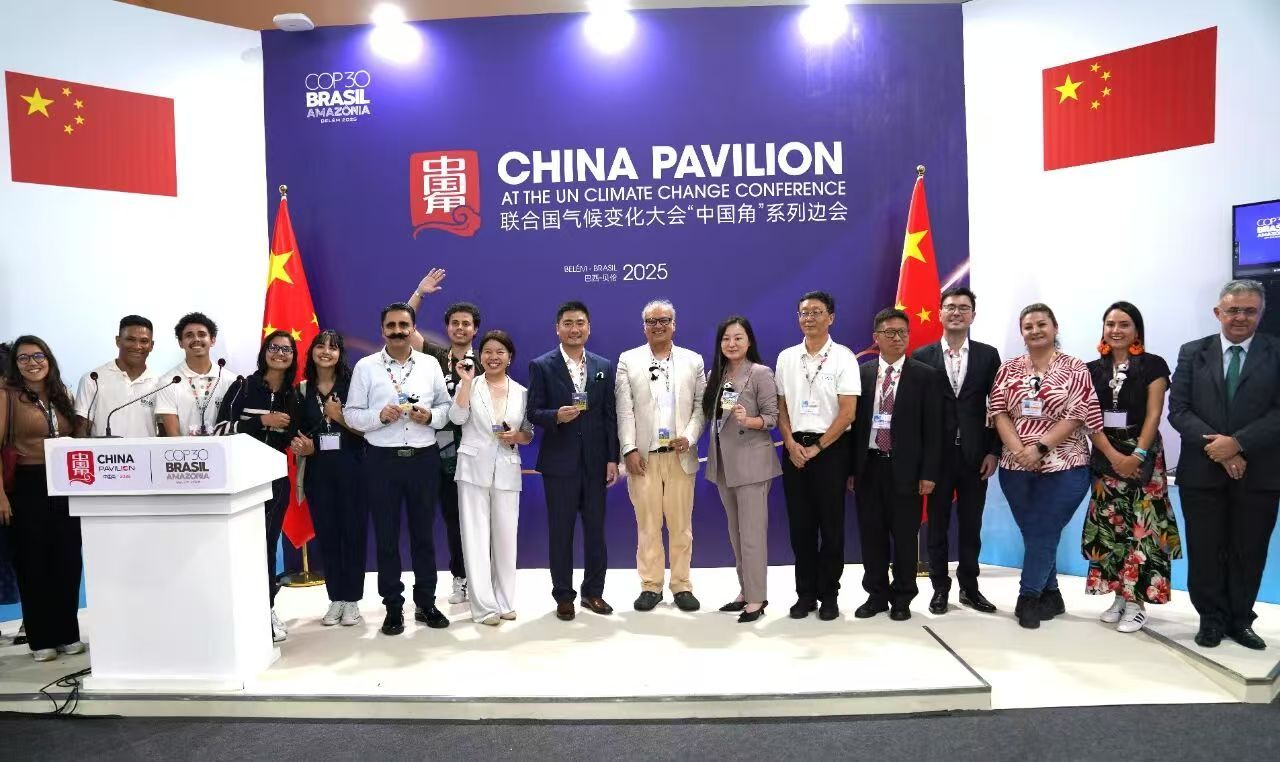

The large presence of Indigenous peoples in the halls of COP was memorable, as was the prominent role of China in the Blue Zone, making the U.S. absence all the more noticeable.

The huge fire that broke out in the Blue Zone on the second-to-last day was of course memorable, and a little too on-the-nose as a symbol of our planet burning!

On a lighter note, the ice cream at the Sorveteria Cairu stand, featuring flavors of the Amazon like cupuaçu (my personal favorite), bucari, açai and taparebá, and of course excellent local chocolate, was a real highlight of COP30 in Belém.

What was achieved at COP on a personal or broader scale?

For my own research on the international politics of climate change and decarbonization, attending the conference—this was my first COP—was fascinating. I learned a huge amount both about how the various parts of COP operate, and from the panels I attended. I also expanded my network of contacts with researchers and policy-makers from around the globe—the gathering of so many people working on the myriad aspects of the climate problem is really invaluable, in much the same way that academic conferences are valuable to pull together people working on various aspects of a particular discipline from all over the world.

On a broader scale, not nearly enough was achieved in the official negotiations, although the agreement to triple finance for adaptation was important. It will be very interesting to see whether the new initiative, led by Colombia and the Netherlands—spurred by disappointment with the agreement reached in Belém—will have legs. It could be an opportunity for like-minded countries to move forward with the transition without requiring consensus from obstructionist countries, including our own.

Any missed opportunities?

Globally, the world missed an opportunity, yet again, to agree to move from fossil fuels quickly enough. But, again, that is not particularly surprising given the interests of petrostates and the structure of COP.

And while the fire fortunately caused no serious injuries, it did disrupt events for the last day-and-a-half of the conference.

Robbie Parks, assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health

What were your main takeaways and most memorable moments from the conference?

Leaving COP30, I am carrying a real mix of emotions. On one hand, I am genuinely encouraged by how much progress was made in positioning health as a powerful lever for climate action. Seeing the Belém Health Action Plan take shape, watching key health metrics finally make their way into the Global Goal on Adaptation, and sensing real momentum toward increased funding for climate adaptation—all of that felt like a major step forward.

In particular, the People’s Plenary on the last Friday was very memorable and moving. The event involved all parts of civil society, and ended with a rousing call for everyone to keep climate momentum going. I was also in the building when the fire occurred, which was quite unfortunate.

What was achieved at COP on a personal or broader scale?

On a personal level, the conference was very meaningful. I had the chance to meet so many passionate people from all over the world, each bringing their own expertise, energy and determination. Being surrounded by that kind of dedication was deeply inspiring, and it has made me want to get much more involved at COP31. Watching negotiators and advocates work tirelessly reminded me how much collective effort goes into every step of progress.

Any missed opportunities?

It is hard to ignore what was missing. Some of the most critical components—like a clear, actionable roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels and stronger commitments to protect forests—either stalled or even moved backwards. That felt like a missed opportunity, not only for this COP but for the broader direction of global climate ambition.

Lara Fornabaio, lead researcher at the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, which is part of the Columbia Climate School

What were your main takeaways and most memorable moments from the conference?

At COP30, my work focused on the connected challenges of food systems, land governance, nature and adaptation—areas where climate ambition often falters because policy, investment and land-use realities don’t line up. Being in the Amazon underscored this contradiction: it’s a globally essential ecosystem, yet simultaneously a frontier for fossil extraction, mining and agricultural expansion.

The Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment co-organized two sessions with Vale Base Metals on embedding nature-positive approaches in mining. One session examined where nature-based solutions can realistically scale and what institutional gaps remain; the second convened practitioners across mining companies, innovators, and civil society organizations to discuss what tools can practically support the implementation of nature-based solutions on the ground. I also joined a session on climate-resilient food systems, looking at innovations across fertilizers, agri-tech and finance.

Beyond the formal agenda, I spent much of my time with existing and potential new partners advancing our SDG-Based Coffee Plans—pilots we’ve tested in Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica—and exploring how similar producer-centered planning approaches could guide transitions in sectors like livestock. Our aim was to ground implementation in coherent planning and aligned incentives, rather than isolated initiatives.

What was achieved at COP on a personal or broader scale?

My goal was to move conversations toward collaborative transition planning, to help governments, companies, financiers and communities plan the transition together rather than through parallel, siloed efforts.

I also hoped to bring clarity to the growing attention on nature. My aim was to highlight that nature is a public good, therefore, most of its benefits cannot generate private returns. This means that large-scale conservation and restoration require public policy, regulation, and long-term public or concessional funding. While private finance can help in a few narrow cases with direct dependencies or revenue-generating activities, relying on markets distorts priorities, enables continued pollution, and often harms communities.

COP30 reinforced how urgently we need coherent, investable roadmaps for the transformation of our energy and food systems. Importantly, COP30 made clear that implementation—not new pledges—is where progress will be made. For us, that means helping partners build the enabling conditions that actually move transformations forward: credible planning, stronger land governance, fair and climate-aligned value chains, and investment models that recognize the true social and ecological value of nature. The next phase requires coordination, not just ambition.

Source link

Olga Rukovets news.climate.columbia.edu