1. Introduction

Zingiberales is a monophyletic order and has a widespread presence in subtropical and tropical regions, consisting of two subclusters: the ‘banana cluster’, including Heliconiaceae, Musaceae, Lowiaceae, and Strelitziaceae, and the ‘ginger cluster’, encompassing Costaceae, Zingiberaceae, Cannaceae, and Marantaceae [

1,

2,

3]. Petaloid staminodes are a key feature shared by the four families in the ginger cluster and typically occupy most stamen positions in fully developed flowers [

4,

5].

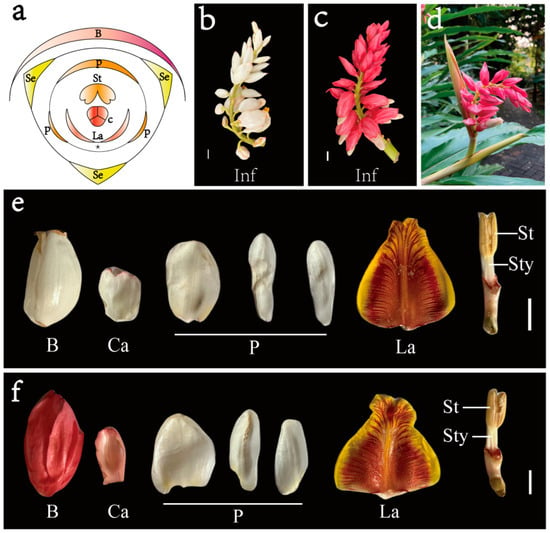

Alpinia hainanensis, an ornamental plant in the Zingiberaceae family, is particularly striking due to its cicada-wing-like petals and vividly colored labellum, enhancing its ornamental appeal. The floral structure of

Alpinia comprises four distinct whorls (

Figure 1a). The outermost whorl is a perianth with three sepals. The androecium features one fertile stamen and five staminodes, with two staminodes integrating to a distinct abaxial labellum, two degenerating to small appendages at its base, and the other disappearing. The innermost whorl is a pistil with three carpels. In most flowers, stamens are primarily reproductive and barely enhance flowers’ visual appeal.

Alpinia deviates from this norm, with its mature flowers having an inconspicuous perianth that plays a minor role in the floral display. Instead, the labellum, formed from two fused petaloid staminodes, takes on a stamen-like role but is visually more like the perianth. Therefore, the floral display in

Apinia is primarily attributed to the labellum.

Flower color and pattern are widely acknowledged as key decorative traits, serving as visual markers crucial for flower organ identity. Unlike the white bracts of

A. hainananensis (

Figure 1b), a novel ornamental trait has emerged in the cultivar

A. hainananensis ‘Shengzhen’, characterized by a striking inflorescence with appealing pink bracts (

Figure 1c,d). The anatomical differences between the white-bracted

A. hainanensis and the pink-bracted ‘Shengzhen’ are shown in

Figure 1e,f, respectively. Previous research has illuminated the mechanisms behind flower pigment production [

6,

7,

8]. In particular, studies on

Alpinia species have identified the factors responsible for the orange and yellow labellum coloration, with orange hues attributed to the combined effects of anthocyanins and xanthophylls, and yellow hues linked to flavones, flavanols, flavanones, additional xanthophylls, and carotenes [

9]. While much attention has been given to pigment biosynthesis in floral tissues [

6,

7,

8], the specific mechanisms behind bract pigmentation in

Alpinia remain underexplored. This study contributes to the current understanding of the processes driving color variation in

Alpinia bracts, offering valuable insights into floral evolution and the development of ornamental cultivars with enhanced aesthetic appeal.

In most flowering plants, naturally occurring pigments such as anthocyanins, flavonoids, and related compounds are key determinants of floral coloration. These flavonoids offer a wide spectrum of pigments, with anthocyanins producing colors ranging from orange to blue, while flavonols, aurones, and chalcones contribute to yellow hues, accounting for much of the color diversity in flowers [

10]. Anthocyanins are water-soluble compounds present in vascular plants, characterized by diverse substituents on the B ring of the flavonoid core [

10,

11]. To date, over 700 distinct anthocyanidin variants have been identified, predominantly derived from delphinidin, cyanidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, petunidin, and malvidin [

12]. Specific anthocyanins contribute to different hues. Pelargonidin and cyanidin are responsible for red shades in flowers and fruits, while peonidin influences purple-red tones. Blue and violet hues are predominantly associated with delphinidin, petunidin, and malvidin [

13]. The way anthocyanin accumulation influences coloration can differ between species. In the case of

Prunus persica and

Camellia japonica, cyanidins give rise to pink and red petal colors [

14,

15]. Delphinidins, which typically produce pure blue petals, may show different effects in specific species. In transgenic

Rosa. hybrida, delphinidins can reach up to 95%, yet the expected pure blue coloration is not always observed, highlighting the species-specific nature of anthocyanin pigmentation [

16].

Flavonoid biosynthesis is highly conserved across many seed plants [

8,

17,

18]. This process includes a sequential of reactions converting phenylalanine into anthocyanins, flavones, flavonols, and other flavonoids and has been extensively studied in species like peony, safflower,

camellia, and

Canna [

15,

19,

20,

21]. This biosynthetic pathway comprises two phases: the early phase, involving key enzymes such as phenylalanine ammonialyase (PAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarin CoA ligase (4CL), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), and flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H); and the late phase, mediated by flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), flavonoid 3′,5′-Hydroxylase (F3′5′H), flavonol synthase (FLS), dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), and glucosyltransferase (GT) [

22,

23]. These enzymes play crucial roles in catalyzing reactions that lead to specific pigmentation patterns, including stripes and spots, which determine the coloration and floral displays in numerous plants.

Transcription factors (TFs) bZIP, MYB, WD, bHLH, and MADS-box are instrumental in regulating anthocyanin synthesis, particularly through their interactions with the promoter regions of key biosynthetic genes [

24,

25,

26,

27]. MYB, bHLH, and WD40 families can function independently or cooperatively to form the MYB-bHLH-WD protein structure [

28,

29]. MYB plays an especially critical role in plant anthocyanin synthesis. Numerous R2R3-MYBs have been recognized, most positively regulating anthocyanin production, although a smaller subset functions as inhibitors [

30,

31,

32].

Despite a range of studies elucidating the molecular functions of flower color via the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway [

33,

34,

35], it remains important to account for species-specific differences, as no universal rules apply across all plants. Each species likely harbors unique metabolic pathways and gene sets governing pigmentation, necessitating a specialized analysis to understand the nuances of

A. hainanensis’s flower color. The UPLC/ESI-Q TRAP-MS/MS technique is exceptionally suited for metabolite profiling and has been commonly implemented in various species, such as tomatoes, strawberries, lilies, and tree peonies [

36,

37,

38,

39]. To investigate pigmentation differences between wild-type bracts (AhWb) and the ‘Shengzhen’ cultivar bracts (AhPb) of

A. hainanensis, we adopted a comprehensive approach, combining flavonoid metabolomics with transcriptomics. This strategy is crucial for revealing the involved metabolic pathways and identifying key enzymes or genes driving differential coloration. Our study identified the predominant anthocyanin types in AhWb and AhPb, established a comprehensive flavonoid metabolic and transcriptomic profile for

A. hainanensis, and highlighted key candidate genes and TFs associated with the differential anthocyanin accumulation. This study advances our knowledge of the molecular underpinnings influencing flower color diversity and offers valuable insights for upcoming genetic and breeding strategies in

Alpinia.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we conducted comparative metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses to uncover the mechanisms underlying differential pigment accumulation in bracts between the wild-type and ‘Shengzhen’ cultivars of A. hainanensis. We identified significant differences in flavonoid metabolites and gene expression patterns between the two bract types. The bract of the ‘Shengzhen’ cultivar exhibited a higher abundance of anthocyanins, particularly cyanidin and peonidin derivatives, which contributed to its distinct pink coloration. The differential expression of key structural genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis, such as AhPAL, AhCHI, and AhGT, was identified as a major driver of anthocyanin accumulation. Our results highlight that the pink bract color in ‘Shengzhen’ arises from a coordinated upregulation of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes and the activation of specific UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) involved in anthocyanin glycosylation. Notably, the upregulation of AhAOGT, AhUGT77B2a, and AhUGT77B2c correlated positively with the accumulation of cyanidin and peonidin derivatives, underscoring their roles in pigment stabilization and color intensity.

These findings advance our understanding of the molecular basis of bract coloration in A. hainanensis and provide valuable resources for the development of ornamental cultivars with enhanced aesthetic appeal in Alpinia. Furthermore, the integrated metabolomic-transcriptomic approach highlights the importance of species-specific regulatory networks in flavonoid biosynthesis, offering insights into the evolutionary diversification of plant pigmentation systems. Future research may focus on the functional validation of the identified candidate genes and further exploration of the regulatory mechanisms governing anthocyanin accumulation in Alpinia.