1. Introduction

Aphids are a group of sap-sucking insects, and many of them are important pests because of their large population sizes and ability to carry and transmit plant viruses. They are generally small insects with soft bodies. To defend against natural enemies such as ladybugs (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), gophers (Diptera: Syrphidae), and parasitic wasps (Hymenoptera), aphids have evolved some defensive adaptations, i.e., siphunculi and their secretions, dense wax cover, drop-off, and thanatosis [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Some aphid species have also evolved alternative defense strategies by establishing food-based mutualistic relationships with ants [

5]. They excrete excess sugars gained from host plants, along with water, as honeydew, which is a tasty meal for the mutualistic ants. The ants protect the aphids from their natural enemies to keep the honeydew resources [

6,

7,

8].

Many aphids have polymorphisms in body color. For example, the pea aphid

Acyrthosiphon pisum has two body colors, green and red, and the peach aphid

Myzus persicae has three body colors, yellow, green, and red. The polymorphisms of aphids can occur within the same population or shift rapidly between generations [

9]. The body color of aphids is affected by many factors, such as temperature, host species, light, symbiotic bacteria, and host plant quality [

9]. Natural enemies and mutualistic ants also influence the body color composition in aphid populations. The seven-spotted ladybug

Coccinella septempunctata prefers to prey on the red morphs in pea aphids, while the green morphs are more parasitized by parasitic wasps [

10]. The dark green morph of cotton aphid

Aphis gossypii is more susceptible to parasitic wasps than lighter-body-color morphs [

11]. The presence of the mutualistic ant

Lasius japonicus can change the proportions of green and red morphs in the aphid

Macrosiphoniella yomogicola populations [

12].

As phytophagous insects, the performances of aphids are closely related to the conditions of host plants. On plants with higher levels of nutrients, aphids produce offspring that are larger, grow faster, and are more fecund [

13,

14]. Nutrients in plant sap are thought to determine the food quality for aphids, and increased levels of these nutrients can promote aphid growth and reproduction [

13,

15]. However, the distribution of plant nutrients across plant organs is not uniform [

16,

17]. Thus, feeding on different parts of a plant can directly affect aphid performance. For example, populations of the aphid

Macrosiphoniella tanacetaria feeding on the stems of

Tanacetum vulgare grow faster than their counterparts feeding on the leaves [

18]. Furthermore, host plant condition can also affect the ants through the aphid-produced honeydew, a bottom-up effect [

19]. For example, defensive substances in plant sap are taken up by aphids and then excreted out through honeydew. Honeydew containing these substances has an avoidance effect on ants, which in turn attenuates their mutualistic relationship with the aphids [

20,

21]. To gain more high-quality honeydew, some ants actively move tended aphids to feed on young plant parts or plants with higher nutritional value [

22,

23].

The red imported fire ant (RIFA),

Solenopsis invicta, is a highly destructive invasive species and has established extensive mutualistic relationships with cotton aphids in the southern United States since its invasion of North America [

24,

25]. The RIFA suppresses the populations of natural enemies in cotton fields, leading to the outbreaks of some major pests such as the cotton aphid [

26,

27]. Cotton aphids have a wide range of body colors, including yellow, light green, and dark green. Individuals with a certain body color can produce offspring of various body colors [

28]. Yellow morphs are the smallest in body size, with the slowest growth rate and the lowest fecundity, while dark green morphs are the largest, with the fastest growth rate and the highest fecundity [

29,

30]. The body color of cotton aphids can be influenced by temperature, host species, host quality, and biotic interactions [

11]. Yellow morphs are mainly produced at temperatures above 25 °C [

30], and darker green morphs are observed on the cotton plants with higher nitrogen content [

13]. The body color composition of a cotton aphid colony can also be influenced by interactions with mutualistic ants and natural enemies. When tended by the mutualistic Argentine ant

Linepithema humile, the cotton aphids produce more light green morphs in the offspring [

11], whereas the presence of the predatory ladybug

Hippodamia convergens leads to more winged morph in the offspring that further produce mainly yellow morphs [

28].

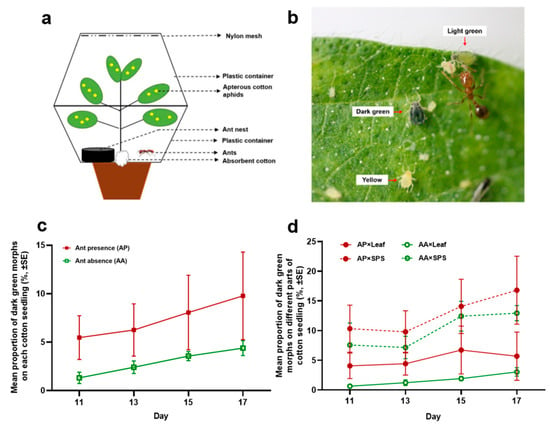

We have previously observed opposite effects of mutualistic RIFAs and predatory ladybugs on the distribution pattern of cotton aphids on cotton seedlings, with more individuals distributed on the stems, petioles, and sprouts in the presence of ants but more on the leaves in the presence of ladybugs (unpublished data). Since food quality is an important factor influencing the variation in aphid body color and varies across different parts of host plants [

9], we hypothesized that the body color compositions varied among the cotton aphid morphs distributed on different plant parts, which can be impacted by the biotic interactions and may have adaptive significance. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the changes in the body color compositions, in particular the dark green morphs, of cotton aphids distributed on different parts of a cotton seedling in the presence of mutualistic RIFAs or predatory seven-spotted ladybugs compared to the colonies without any interspecific interactions under constant laboratory conditions.

4. Discussion

Color polymorphisms are a common feature of many aphid species. Cotton aphids exhibit a wide variety of body colors, ranging from pale yellow to dark green. In the present study, we found that the proportion of dark green morphs of cotton aphids on stems, petioles, and sprouts (SPSs) was significantly higher compared to that on leaves under constant laboratory conditions. The presence of mutualistic fire ants increased the proportion of dark green morphs among the cotton aphids distributed on either leaves or SPSs, whereas the presence of predatory ladybugs led to an opposite effect on the proportion of dark green morphs, particularly on SPSs. However, significantly decreased body size was also found in the aphids, with the same body color, distributed either on SPSs or leaves that were tended by ants, suggesting the presence of a cost generated from the interactions with ants.

As phytophagous insects generally prefer to feed on more nutritious plant parts, the spatial distribution of nutrients in host plants can directly shape the within-plant distribution pattern of aphids [

31,

32]. In plants, the vigorously growing parts (e.g., upper parts of stems, newborn leaves and sprouts) may contain relatively higher levels of soluble nitrogenous substances due to high protein synthesis or degradation activities than mature leaves [

16,

17]. A previous study has reported that the elevated concentration of nitrogen in cotton plants can increase the proportion of dark green morphs in cotton aphid colonies [

13], which may explain the higher proportion of dark green morphs on SPSs observed in this study. Moreover, our results showed that the body sizes of the cotton aphids distributed on SPSs were larger than those on leaves. These findings suggest better performance of cotton aphids on SPSs than on leaves.

In the present study, we found that the proportions of dark green morphs declined in the cotton aphid colony after a predatory ladybug was introduced, which was mainly due to a dramatic decrease in the dark green morph proportion on SPSs compared to that on leaves. Predatory ladybugs have been found to be able to evaluate the quality of prey based on the organs of the host plant to save time and energy [

33]. We observed that ladybugs spent longer periods of time moving or staying on the upper part of cotton seedlings. Aphids may be able to sense ladybug activity and thus quickly move to the leaves or drop off from the plant to escape predation [

34]. Predators are able to select more nutrient-dense foods to increase predation efficiency [

35]. Seven-spotted ladybugs can recognize prey by exploiting color differences between the prey and the background [

36]. Hence, seven-spotted ladybugs may be able to discriminate between dark green and yellow cotton aphid individuals by vision, with a potential preference for dark green morphs, and forage more frequently in the areas mainly occupied by dark green individuals. In addition to predatory natural enemies, parasitoid wasps are more likely to attack the dark green morphs in the cotton aphid colonies [

28]. These findings imply that dark green morphs probably suffer greater attack by natural enemies than yellow morphs, and the reduction in the proportion of dark green morphs, particularly among the individuals on SPSs, may decrease the attacking risks from natural enemies in the absence of protective ants.

In most mutualistic relationships, members of different parties pool complementary abilities by exchanging services for their mutual benefit [

37]. Although we did not observe the behavior of ants carrying aphids to specific parts of the plant during the experiment, the ants could use other means such as chemical signals to regulate the behavior of aphids. A recent study has found that perception of RIFA trail pheromones alters the behavior and reproductive performances of cotton aphids [

38]. Thus, aphids that are attended by ants may have sensed the presence of ants, resulting in a change in the production of offspring in different body colors that differed from those of the control. The higher proportion of larger morphs in a cotton aphid colony may guarantee ants access to more honeydew resources, allowing them to reap more rewards from the mutualistic relationship.

The mutualistic associations between

S. invicta colonies and honeydew-producing hemipterans in invaded areas are widespread [

39]. The invasive fire ants monopolize carbohydrate sources provided by the hemipterans over native ant species [

40,

41]. Exploitation of honeydews by RIFAs is important in their invasion success [

42]. The RIFA-tended cotton aphid colonies gain benefits from ant protection, having much larger population sizes than the untended colonies [

43]. The increased proportions of dark green morphs in the RIFA-tended aphid colonies may also account for the rapid increase in colony size of cotton aphids, which, in return, facilitates outbreaks of invasive fire ants.

Aphids have been found to show some changes in behavior, life history, wing differentiation, and body structure in order to be more adapted to mutualistic ants [

2,

44,

45]. However, the mutualism associated with ants can impose some negative effects on aphids, leading to smaller body size, slower individual development, and reduced reproductive capacity. These effects are thought to be attributed to the high demand for honeydew by the mutualistic ants and force the aphids to use more energy to secrete more honeydew or synthesize sugars preferred by the ants [

46,

47,

48,

49]. In the present study, we found that the cotton aphids in either yellow or dark green that were attended by ants were smaller in body size than their counterparts without ant-tending, suggesting a negative effect of ant attendance on cotton aphids. However, for aphids, the negative effects may be far less than the attrition caused by producing winged offspring that escape the danger [

50]. Therefore, the results of the present study suggest that cotton aphids may be able to take advantage of ant protection as a favorable condition by distributing on nutrient-rich parts of plants, thereby producing larger, faster-growing, and more fecund phenotypes to satisfy the ants’ demand for honeydew and to compensate for the costs from mutualism.

In summary, the present study found that the proportion of dark green morphs in cotton aphids is closely related to their distribution sites on host plants, with a higher proportion on the nutritious parts, revealing a potential strategy for the aphids to actively change the colonial body color composition. By using this adaptive strategy, aphids can increase the proportion of dark green morphs that are larger and more fecund to gain more benefits and/or minimize the costs when the mutualistic ants are present, and decrease the proportion of dark green morphs that have greater attacking risks from natural enemies in the absence of mutualistic ants. These findings improve our understanding of the ecological implications of body color polymorphisms in aphids.