COP30 has ended, the negotiations have closed and global leaders have returned home. But for millions of people on the frontlines of the climate crisis, nothing has ended. The floodwaters have not receded. The crops destroyed have not returned. The next storm has not paused to wait for the next summit.

In South Sudan, where I grew up, the climate crisis was never a distant threat. It was the texture of daily life. My ancestral village of Jalle, Bor—where my grandfather is buried—has been underwater for years. About 700,000 South Sudanese people endure catastrophic flooding annually, just like other vulnerable populations across the world. When floodwaters rise, homes vanish, diseases spread and families are pushed deeper into poverty. As a result, today, more than 76 percent of the population of South Sudan lives below the poverty line.

When we were children, we relied on the knowledge of our elders—the call of birds, the shape of clouds, the rhythm of winds—to read the weather. But our human-induced changes bent nature out of recognition. The signs no longer matched what our parents and grandparents had known. The climate we inherited had been replaced by something unfamiliar and unforgiving.

Later, living as a refugee in Uganda, I studied agriculture to confront the hunger that shaped our lives. But one season, floods wiped out 90 percent of my crops. I realized then that climate resilience required more than seeds and hope. It required understanding.

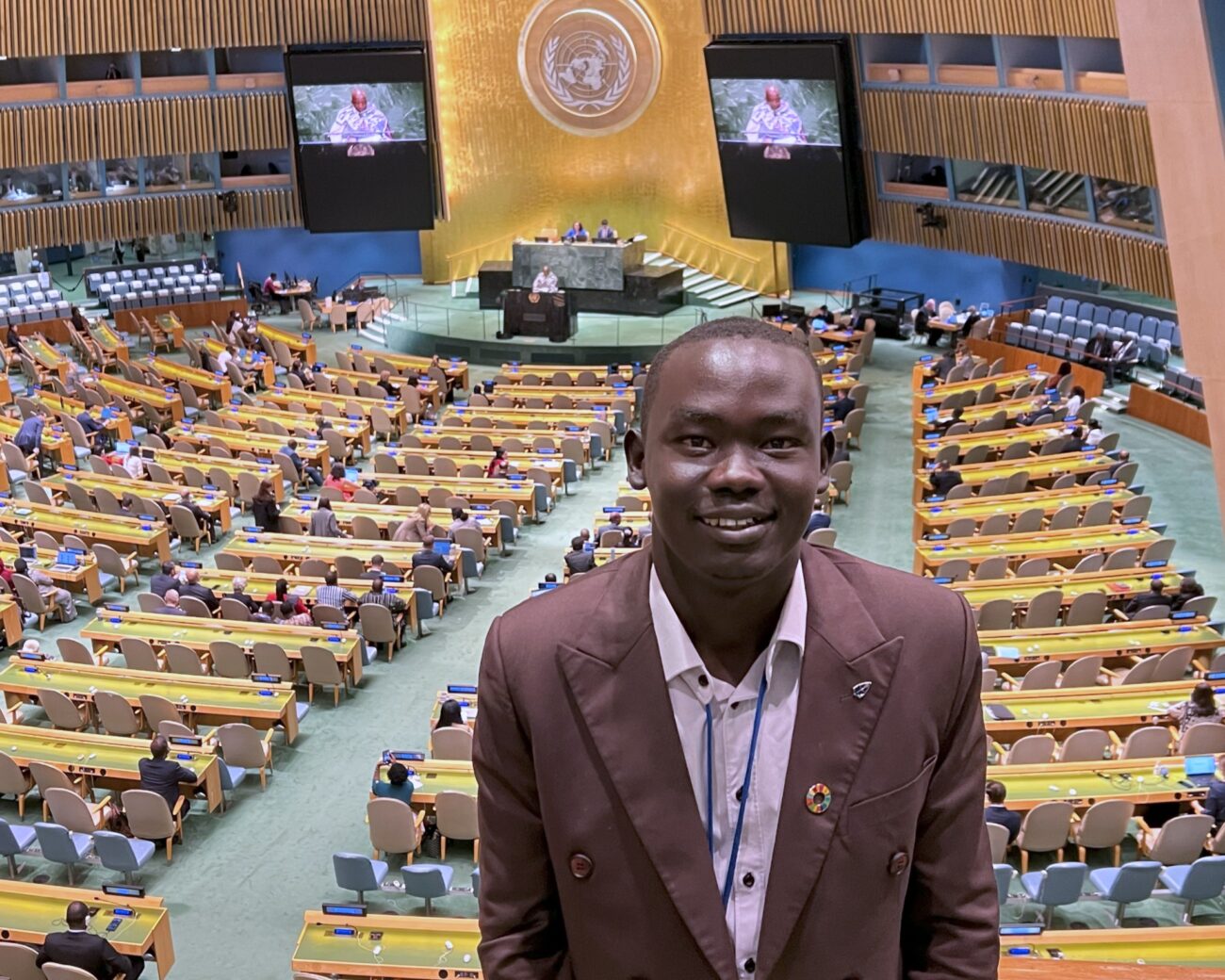

That realization brought me to the Columbia Climate School and eventually to intern with the United Nations Secretary-General’s Climate Action Team, where I analyze national climate plans from nearly 200 countries. I followed COP30 closely, watching the diplomacy unfold. The debates were fierce—over fossil-fuel phaseout language, adaptation funding and responsibility. But as someone whose childhood memories are built on disaster and constant adaptation, the gap between negotiation rooms and the real world has never felt wider.

Columbia Global recently shared my journey, quoting Assistant Secretary-General Selwin Hart, who said: “At a moment of geopolitical uncertainty and division… Anyieth is helping ensure the voices of those on the frontlines of the climate crisis are heard, respected and never forgotten.”

And yet, COP30 showed once again how far global climate policy still is from the lived experience of frontline communities.

The conference wrestled over fossil fuel language, with no substantial agreement on climate finance, while the world continues to under-invest in adaptation—the one area that determines whether people survive the warming that is already unavoidable. Tripling investment in adaptation, as the conference settled on, is not the problem; the problem is how and by which countries this will be funded and how that investment will get to the intended people. Adaptation is not a side conversation; it is a lifeline.

For communities like mine, adaptation means early warning systems that actually reach villages. It means flood defenses that hold. It means climate-resilient farming, safe drinking water, reliable infrastructure and health systems equipped for disease outbreaks. It means decision-making power in the hands of the people living the crisis, not only those debating it.

Adaptation is also a matter of equity. The people suffering the most from climate impacts did the least to cause them. Yet promises of adaptation financing remain stuck in slow-moving pipelines. Broken commitments have become their own form of climate injustice.

As someone whose childhood memories are built on disaster and constant adaptation, the gap between negotiation rooms and the real world has never felt wider.

The imbalance between mitigation and adaptation is dangerous. Mitigation is essential, but it is not enough—not for a farmer whose fields flooded this year and will do so for years to come, not for a family displaced by a hurricane, not for a village that cannot rebuild fast enough.

Alvin Toffler once wrote that the illiterate of the 21st century are those who cannot “learn, unlearn and relearn.” That insight defines climate adaptation. The world must relearn how to protect itself. Communities must learn climate literacy so that misinformation does not deepen vulnerability. Governments must unlearn the habit of treating adaptation as optional and relearn prioritizing it.

During COP30, Indigenous peoples protested in Belém, demanding a seat at the table. Their presence was not symbolic; it was a reminder that climate solutions without frontline voices are incomplete. Indigenous knowledge systems have preserved ecosystems for centuries. They must not be sidelined as the planet enters its most precarious phase.

Belém, at the edge and the gateway of the Amazon, carried emotional weight. But symbolism is not protection. Symbolism does not keep homes from collapsing or crops from failing or lives from being lost. What matters now is whether world leaders treat COP30 as an endpoint in negotiation, or a starting point for action.

Future climate summits must measure success not only in diplomatic breakthroughs, but in lives protected and real emissions cuts in every corner of the world. They must ask questions like: How much GHG did we cut? How much more action do we need to reach net zero and maintain the 1.5 degree Celsius benchmark? Who got early warning systems? Who rebuilt? Who survived?

As someone who grew up surrounded by climate loss and who now works inside the global climate system, I know how fragile the bridge is between promises and protection. But I also know what is possible when science, policy and lived experience come together.

COP30 has ended, but the climate crisis continues with unforgiving clarity. For millions like me, time is not counted in conferences. It is counted in flood and drought seasons, in the frequency of disasters, and in the shrinking margin between survival and catastrophe.

For us, just as Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said, “Climate change is no longer a threat of the future. It is a tragedy of the present.” And the world can no longer afford to respond after the damage is done.

Anyieth Philip Ayuen is a recent graduate of the M.A. in Climate and Society at Columbia Climate School. He currently works as a program management intern with the United Nations Secretary-General’s Climate Action Team, supporting the analysis of nationally determined contributions, climate media monitoring and policy development for COP30.

Views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Columbia Climate School, Earth Institute or Columbia University.

Source link

Guest news.climate.columbia.edu