The implementation of reverse engineering technologies in the field of hard-to-reach diagnostics is currently one of the research challenges in several industry sectors, including manufacturing, transportation, energy, medical, and other sectors [

1]. Visual inspection as a method of engineering diagnosis has been used for several decades in the diagnosis of hard-to-reach areas [

2]. In certain areas of its application, this diagnostic method is the fastest and least expensive, and in certain cases, it is the only usable method within non-destructive testing. For this purpose, endoscopic devices, especially industrial videoscopes, are used. Their utilization in the field of diagnostics of hard-to-reach places provides several advantages, e.g., rapidity of obtaining the necessary information, relatively low costs of the technology compared to other technologies of non-destructive testing, etc. The main disadvantages of conventional endoscopic inspection can be considered to be the acquisition of only images of the surface without spatial information about its shape and surface [

3]. For this reason, it is not possible to effectively and accurately measure the geometry of the surface geometry features of objects and their extent, which include cracks, defects, and other damage. To obtain this information, particularly the distance between the sensor and the surface points of objects, research is being conducted on the implementation of reverse engineering elements in the field of diagnostics of hard-to-reach places. A challenge in this area is the use of reverse engineering techniques within confined spaces. The reverse engineering techniques currently used require a certain minimum amount of space for the implementation of the digitization process in order to use the digitization equipment. Minimum mutual distance between the sensors and the object are also required. Furthermore, conventional digitizing devices are, in most cases, designed in sizes that do not allow their utilization within hard-to-reach places. Due to technological advances, sensor, reverse engineering, and endoscopy technologies are continuously being developed with the aim to develop technologies with higher resolution, higher accuracy, and smaller dimensions. This fact allows their progressive implementation in the field of hard-to-reach diagnostics, and this paper is dedicated to this issue.

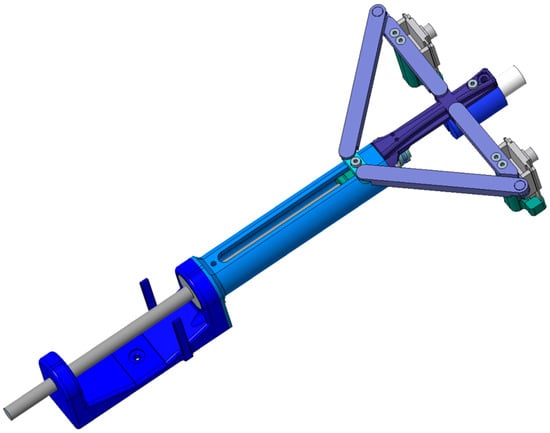

To address this challenge, an in-depth analysis of the current state of the art and knowledge in the field of reverse engineering and its available techniques and technologies is needed. Subsequently, it is necessary to describe the implementation of non-destructive testing and the possibilities of using reverse engineering in areas of hard-to-reach places. With this knowledge in mind, it is necessary to design a prototype digitizing device usable in these areas. A suitable reverse engineering technique needs to be selected for use within this facility. With respect to the available reverse engineering techniques, it is necessary to analyze them step by step and arrive at a suitable way of implementing this technique. For this proposal, it is necessary to think with an “outside of the box” strategy based on the use of innovative ideas and atypical solutions, as there are currently no commercially available digitizing devices for use in the field of diagnostics of hard-to-reach places. The correct selection of available reverse engineering techniques and their use in an innovative way is crucial.

In the field of digitizing hard-to-reach places, Ref. [

4] proposed a 3D digitizing device based on surface scanning using multiple images at different angles and using structured light techniques without the need for calibration. In digitizing using this device, unlike conventionally structured light-based digitizing devices, there is no need to calibrate the device, after which it would be necessary to maintain the device in the same location in space. As a result, details of the shaped surface can be better captured at multiple angles, while the accuracy of the acquired data is higher. In the digitizing process, it is possible to change the position of the projector or camera within the space but not of both in the same process. Subsequently, the researchers of [

5] developed a self-calibrating active digitizing device using a laser scanning technique employing line lasers and a single camera. A device with a projector of two laser lines and a camera was built, and the device can be freely moved within the space during the digitization process, and thus, the surface of the object can be digitized. The device uses a sequence of frames for calibration and depth measurement, during which the laser projector is moved backwards and forwards. The device records a constant point as the intersection of two laser lines at an angle of 90°. Utilizing this technique, the authors of [

6] measured the three-dimensional distance to the gastric surface in medicine by image processing of the stereo matching method. As part of the subsequent research, the authors of [

7] followed up on previous work in digitizing the object using laser techniques and self-calibration. In this work, they presented a 3D dense point cloud acquisition technique based on a laser digitization technique using projection of line lasers onto planar surfaces. As the basic information for 3D data acquisition, the projected laser curves on planar surfaces are captured by a single camera at a viewing angle non-parallel to the laser beam source, where the laser beam source and the projected beam are repositioned, and the camera position is constant in the process. In particular, the description of the process and the numerical calculation required for obtaining a 3D surface model of planar objects by the laser technique can be considered as a contribution of this work. The authors of [

8] presented a 3D endoscopic digitizing device using the “active stereo” technique. The active stereo technique can be defined as a digitizing technique using one or more structured light projectors and one or more cameras, whereby the light pattern of a mesh grid is projected onto an object, and the surface of the object is calculated based on the distribution of the light pattern on the object. The projector was composed of a laser light projector and an optical fiber transmitting the light source to a projector head located on the outside of the endoscope using a thin and flexible tube. The endoscopic device recorded an image with blurring, which had to be compensated for by an algorithm in the endoscope calibration process. In contrast to the structured light technique using the encoding of positional information within shape patterns explicitly, in the active stereovision technique, the intersection lines of the laser beams were implicitly used as reference points for the computation of the surface in space. A complex process was used to calibrate the projector by projecting the image pattern through the display, which was recorded by a separate camera, not an endoscopic camera; then, the laser pattern was projected onto the display. The projected pattern could then be aligned with the shape image on the display. In a practical validation of the device, a distance measurement error of 0.89% and an angle measurement error of 2.17% were recorded. The authors of [

9] presented a method of calibration of a device for measuring the shape and size of objects for the examination of body parts in the field of medical diagnostics, a prototype 3D endoscopic device with an active stereovision technique. The proposed calibration method did not require the use of a calibration camera other than the endoscopic camera, using a device with a spherical surface shape for calibration, and at the same time, there was no need to distinguish between the distance of the calibration camera and the endoscopic camera. The authors of [

10] followed up on previous work and improved the design of the prototype device. Instead of placing the laser beam projector on the outside of the endoscope, the authors implemented it in the head of the endoscope, reducing the diameter of the prototype device head. A diffractive optical element (DOE) was chosen at the end of the projector. Simultaneously, this implementation made it possible to introduce self-calibration of the device. Since the projector achieves 2 degrees of freedom when the device is working and when the device head is moving—namely, displacement in the axial direction and rotation about the axis—they proposed to create a mark on the projector for calibration, which is detected by the endoscopic camera. In this way, the orientation and relative position of the camera and projector can be determined and included in the calculations for calibration. Previous work in the development of a prototype 3D endoscopic device has been followed up on by the authors of [

11]. Focused on calibrating a device whose projector was not statically mounted in the endoscope head, the authors determined that the device could not be pre-calibrated. To eliminate the need for complex and inaccurate calibration of the device using markers on the projector, a neural network was designed that senses and uses 10 point markers from the projected pattern. The device only needs to be calibrated once, and despite projector movement, the device will be correctly calibrated during the digitizing process. The advantage is the ability to digitize surfaces on a larger scale, as the object can be digitized in parts, and the acquired data can be merged. The device has been practically verified by digitizing the inside of a pig stomach, whereby the object was digitized in parts using more than 200 images, and the surface data acquired were combined into a complex model. The authors of [

12] used the measurement of object surfaces employing the GelSight Max device, which uses reflectance transformation imaging against a gel-backed elastomer tactile membrane, for the topographic measurement of stone tool surfaces. This device may be used for surface digitization in hard-to-reach areas, but at present, it can only be used to digitize surfaces of small size and presents limitations in terms of the surface complexity. It is worth investigating the use of this technology for digitization of hard-to-reach areas in future research.

Source link

Adrián Vodilka www.mdpi.com