1. Introduction

Prolonged exposure of diabetes can alter glial cell functions of astrocytes and microglia. Astrocytes modulate the synthesis and transport of nutrients and support neurotransmitter function, whereas microglia respond quickly to CNS injury and insult [

1,

2]. Astrocytic end feet and blood vessels are the major component of the blood brain barrier (BBB) which provides metabolic support to neurons inside the neuroependyma. Thus, any changes in morphology of glial cells not only affect the morphology of cerebral blood vessels, but also cause the breakdown of physiological effects including metabolism and synaptic transmission between the central and peripheral nervous system [

3,

4].

Earlier studies have shown that the diabetic environment can increase glial cell death that impacts neural cells and may contribute to cognitive impairment [

5]. Previous research in our laboratory showed that the type-2 diabetic mouse

db/

db (homozygous for the spontaneous mutation;

Leprdb), is susceptible to neuronal cell death very early following hypoxic-ischemic (HI) insult compared to their heterozygous control, non-diabetic

db/+ [

6].

A completely different pattern of temporal changes in microglia and astrocytic activation and cytokine expression occurred in the

db/

db mouse in comparison to

db/+. The glial cell response was delayed in diabetic brain, and cell death occurred early following ischemic insult [

6,

7]. These defects were associated with increased blood brain barrier permeability (BBB) especially in the caudate at 4 h post ischemia and the cortex by 24 h [

8].

The type-2 diabetic mouse,

db/

db mouse has been commonly used to study the diabetic complications by several researchers and documented a significant mortality and morbidity following ischemic injury [

9,

10,

11]. We don’t know the exact reason of poor recovery because normalizing the hyperglycemia did not improve the stroke outcome either in preclinical or clinical study [

11,

12]. The cerebral microvasculature is another target for chronic diabetic complications and the abnormal permeation of proteins into the brain has been shown in experimental diabetes mellitus [

13]. Therefore, we hypothesized that changes in the baseline activation of glial cells and cerebral blood vessel due to persistent hyperglycemia may make diabetic brains more susceptible to neuronal cell death post ischemia.

Astrocytes are dynamic partners of neurons and provide a substantial amount of energy both as a source of glucose and lactate and help to remove excessive lactate to prevent toxicity [

14,

15]. Microglia is the first line of defense against any injury to preserve a healthy brain. It continuously guards the brain to remove any pathogen or debris to preserve a healthy brain [

16]. Therefore, the integrity and function of the glial cells are utmost important. Hence, in this study, we examined three different brain regions including the motor cortex, caudate and hippocampus because these regions are responsible for motor coordination and memory functions. In addition, these regions of the brain are more vulnerable to death post ischemic insult.

High levels of blood glucose adversely affect the endothelial cells of the cerebrovascular system and consequently cause oxidative stress resulting in the abnormal pathology of neuron and glia cells. Previously, we and others have observed the significant increase of metalloproteinases activity and loss of tight junctional proteins in diabetic brain upon ischemic insult [

17].

In this study, we examined brains from uninjured mice to establish the baseline changes in glial cell morphology and function in diabetic and normal animals. The number of astrocytes and microglia in the motor cortex, caudate, and CA3 region of the hippocampus were quantitated. Glial functions were assessed by blood vessel permeability in the motor cortex and caudate. We found a significant increase in the number of activated astrocytes in the cortex and caudate and the number of microglia/macrophages in the caudate of db/db mice at 12-weeks, along with leaky blood vessels and loss of tight junction protein (TJs) comparison to non-diabetic animals.

2. Materials and Methods

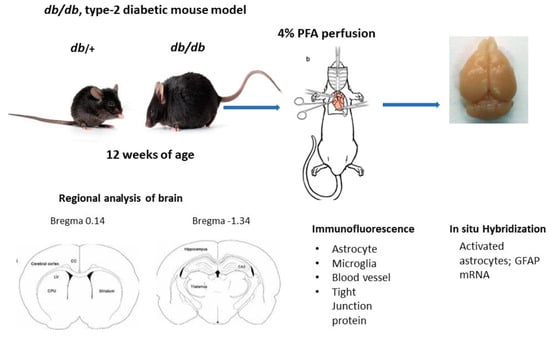

2.1. Sample Collection and Tissue Processing

All the experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Penn State University. Male type-2 diabetic db/db and their heterozygous nondiabetic control db/+ mice were obtained from Jackson laboratory (JAX stock #004456) at 11–12 weeks of age. All mice were housed (2 per cage) in ventilated cages, maintained on a 12 h dark-light cycle with free access to food and water. Post acclimatization, body weight and blood glucose were measured using a tail prick with the BD Logic TM Meter (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and intracardiac perfused with 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS)/4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The fixed brain samples were collected and post fixed in 4% PFA overnight, then cryoprotected with 15% and 30% sucrose gradient. The brains were quickly rinsed with 1× PBS and immersed in cold isopentane (−40 °C) and stored at −80 °C until processing for immunolabeling.

2.2. Immunofluorescence Staining

Brain sections (16 µm) were obtained at different levels, bregma 0.14 mm for motor cortex and caudate and bregma −1.34 for hippocampal region. Brain tissue was washed with 1× PBS for 10 min followed by 1 h incubation with 0.5% H2O2 at room temperature, washed with 0.3% Triton/1× PBS three times for 5 min and blocked with 10% normal goat serum in 0.3% Triton/1× PBS/1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were incubated with one of the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal GFAP (1:500, MAB 360, Millipore Sigma, Lenexa, KS, USA), rabbit polyclonal Iba-1 (1:100, 013-27681, Fujifilm Wako, Richmond, VA, USA, rabbit anti-mouse occludin (1:50, Invitrogen/ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), rabbit polyclonal IgG (1:500, ab150077, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) and tomato lectin (1:500, DL-1178-1, Vector lab, Newark, CA, USA) in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. The next day, sections were washed with slow agitation in 0.3% triton/1× PBS for 3 times for 15 min each followed by incubation with either Alexa Fluor 488 or 546 conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500, Jackson Laboratory, Jackson Laboratory, Boston, MA, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were washed with agitation with h 1× PBS for 15 min followed with DAPI (1:5000, D9542, Sigma) staining for 10 min. Post nuclear staining, sections were washed with 1× PBS, twice and mounted with Aqua Poly/Mount. The images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 900 with Aairy scan/2 Confocal microscope (Zeiss, White Plains, NY, USA).

2.3. Regional Analysis of Glial Cells

Images of different brain regions of

db/+ and

db/

db mice were captured at the same setting under confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 900). The images were analyzed by ImageJ software; 1.54 as described earlier [

18]. The images were color deconvoluted and the threshold was adjusted to reduce the background. The numbers of activated astrocytes that were above 25 pixels and microglia above 10 pixels were counted. At least 4 different brain sections for each region and mouse condition were analyzed and the numbers of cells averaged.

2.4. Hypoxia-Ischemia Model

Hypoxia-ischemia was induced in 8–10 week old male

db/

db and

db/+ mouse by right common carotid artery ligation followed by hypoxia as described earlier [

19]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and mantained at 1.5% isoflurane. The right common carotid artery is exposed and ligated with 3.0 surgical suture. After surgery, mice were allowed to recover for 3 h in their own cage with food and water. Post surgical recovery, mice were kept in a hypoxic chamber (8% O

2) for 20 min in a circulating water bath to maintain body temperature at 35.5 °C. Mice were then returned to their home cage and maintained on 5% glucose water to prevent from ketoacidosis. Mice were humanely euthanized after 10 & 24 h of hypoxia—recovery and brains were fresh frozen in ice-cold isopentane at −40 °C and stored at −80 °C for processing for in situ hybridization analysis.

2.5. In Situ Hybridization

Brains sections were obtained at two levels (bregma 0.14 mm) for cortex and caudate and (bregma −1.34) for hippocampus. Cryosections (16 µm) were analyzed for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) mRNA by in situ hybridization as described earlier [

6,

20]. Rat GFAP (1159 base pair) was transcribed by enzyme T7 and SP6 polymerase for antisense and sense and linearized by PVU II. This probe was labelled

35S to generate riboprobes for in situ hybridization. The brain sections were hybridized with riboprobe at 58 °C for 16 h and then washed with 0.1× SSC at 50 °C for 15 min. The sections were exposed to autoradiographic film for 48 h and scanned for analysis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Two tailed, unpaired Student “t” test was applied to compare the data between non-diabetic and diabetic mice. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 8.0 and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In this study, we determined the changes in baseline expression and activity of astrocytes and microglia in different brain regions in type-2 diabetic mice. The data suggest that there are significantly greater numbers of GFAP positive astrocytes in cortex and caudate, whereas Iba-1 positive microglia/macrophage are only increased in the caudate of db/db mouse compared to db/+. These effects were associated with increased serum IgG permeability in the cortex and caudate and loss of occludin in the cerebral blood vessels in diabetic mice in comparison to non-diabetic controls.

The effect of diabetes on neuroglial cells and vascular changes is the focus of study after several years of study showing that diabetic patients are more susceptible to various neurological and neurodegenerative diseases including to cerebral ischemic injury [

13,

22,

23]. High blood glucose has been shown to cause the higher neuronal glucose toxicity and may be the underlying reason that compromises glial cell activity, necessary for neuronal survival [

24]. Thus, it is important to understand the changes in glial cell activity in type-2 diabetic brain.

The studies from our laboratory disclosed that astrocytes and microglial activations are diminished or delayed in type-2 diabetic, db/db and ob/ob (leptin deficient; homozygous for the obese spontaneous mutation, Lepob) mice post ischemic injury accompanied with increased MMP-9 activity and BBB permeability. These changes led, over time, to significantly greater neuronal cell deaths and compromised recovery post HI injury {Kumari, 2010 #20}. Therefore, in this study we investigated the baseline changes happening in different brain region to understand the pathological changes within the diabetic brain, while evaluating the repair and response of recovery post ischemic insult.

In general, astrocytes are more resistant to cellular damage. However stressed astrocytes lose their control over water movement, release of glutamate, and the balance between intracellular Ca

2+ and extracellular K

+ resulting in edema and neuronal excitability that leads to failed protection of neurons [

25,

26,

27]. In this study, we observed a greater number of activated astrocytes in motor cortex and caudate without any injury in diabetic mice, which suggests that persistent hyperglycemia may activate the astrocytes, therefore regular functions of astrocytes are compromised, and they are more vulnerable to death post injury. Though, we have seen a rapid decline in GFAP mRNA (

Figure 2) and a significant neuronal cell death in

db/

db mice post HI, we did not find any significant change in activated astrocytes in the hippocampal (CA3) region as shown in

Figure 3B,C. Similar to our report, Liu et al. showed a rapid decline of GFAP mRNA starting at 1 h post HI in spontaneously hypertensive rat preceding neuronal death [

28]. These data confirm compromised neuronal-glial interaction, which plays critical role in determining the outcome and repair of CNS injury.

Another important brain cell which maintains the CNS health is microglia, which produces essential cytokines to mediate brain immunological responses [

2,

29]. Previously we reported less activation of microglia and concomitantly delayed cytokines release in

db/

db mice in post ischemic brain [

6]. In this study, we observed a greater number of activated microglia in caudate without any insult suggesting a compromised state of microglia in

db/

db mouse brain (

Figure 4). In this state, the microglia cannot properly respond during post injury, often leading to immune depression within the brain and consequently resulted into greater neuronal cell death.

CNS microglia are very sensitive to any alterations such as stress, diet and aging. Several studies have suggested that diabetic persons are more vulnerable for developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease and the changes in the microglial population and phenotype may play a significant role [

30,

31]. However, we did not find any significant change in Iba-1 positive microglia in hippocampus (CA3) region. Our data are supported by other studies that did not find any change in microglial densities in hippocampal region in high fat diet induced obese male mice, rather suggested that the phagocytic phenotype of microglia causes synaptic engulfment on hippocampal neuron and promotes cognitive decline [

32,

33].

Lastly, we evaluated the vascular changes in

db/

db mouse without any insult or injury because altered BBB structure in diabetes is not clearly defined [

34,

35,

36]. Type-2 diabetic patients have shown higher susceptibility to cerebrovascular disease and underlying defects are unknown. We and others have shown an increased BBB permeability very early in type-2 diabetic mice following ischemic injury [

8,

37,

38]. In this study, we recorded signs of degenerating blood vessels along with loss of a tight junctional protein in the motor cortex and caudate of

db/

db mice (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Earlier, Stauber et al. reported a selective extravasation of albumin not IgG in type-1 diabetic rodent brain [

39] within two weeks duration of diabetes. However, we observed IgG leakage at closer to 8 weeks of diabetes onset. The reason for the difference may be the duration of diabetes and type-1 vs. type-2 diabetic rodent model. Similar to our report, Acharya et al. reported a leak of plasma IgG in the cortex of the porcine model which was affected by diabetes and hypercholesterolemia from 6 months [

40].