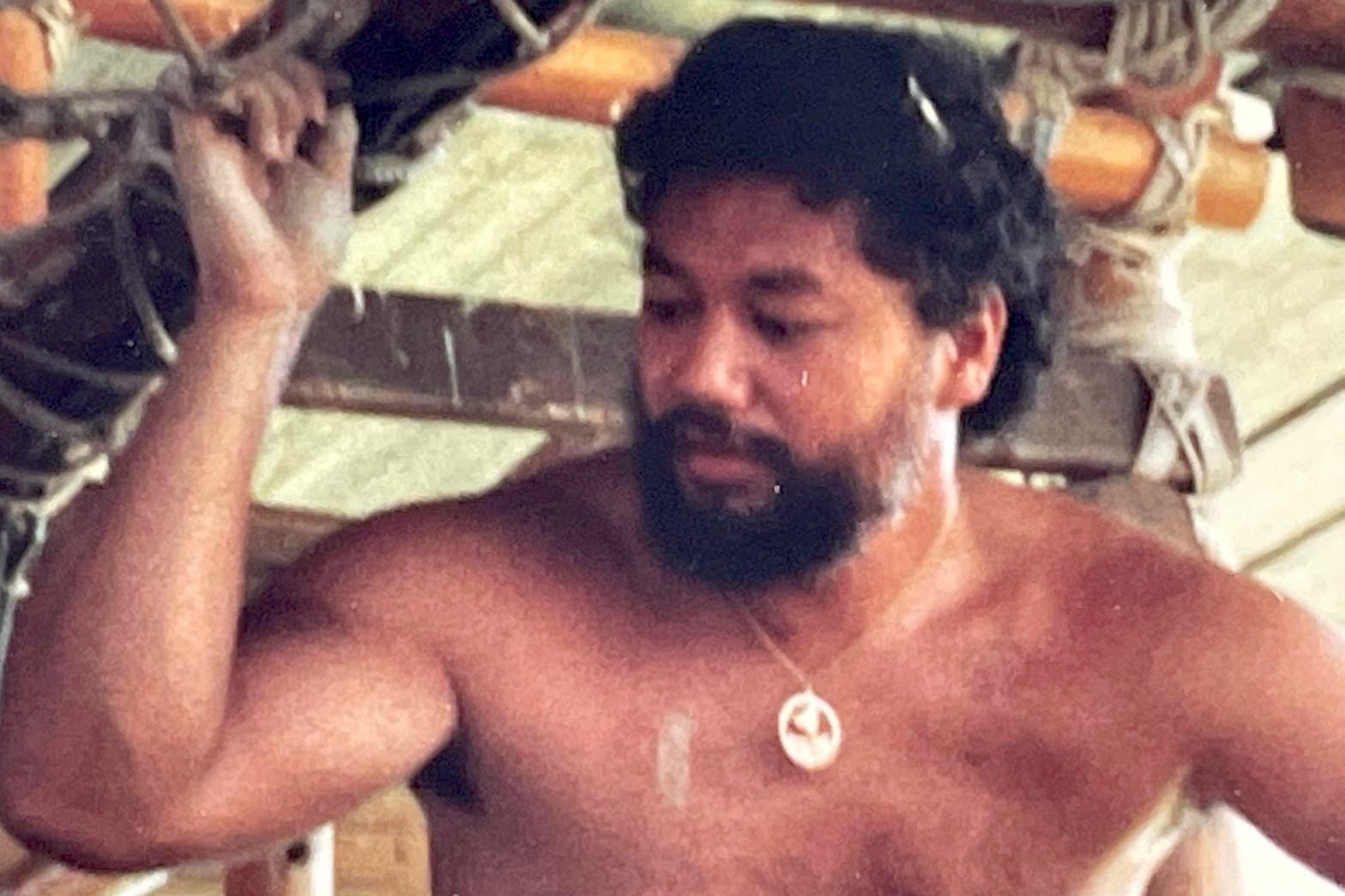

Solomon Kahoʻohalahala steadied himself on the double-hulled voyaging canoe called Hōkūleʻa as a 15-foot swell rose and the vessel took off under the midday sun. He had been paddling since dawn along the south shore of Molokaʻi, and his arms were tired. As the canoe reached the notoriously gusty channel between Molokaʻi and Oʻahu, the crew unfurled her sails. Suddenly Hōkūleʻa was racing, surfing waves that rose so high they blocked the view of Diamond Head Crater, a high volcanic cone on Oʻahu.

It was the summer of 1975, and Kahoʻohalahala was a 24-year-old Native Hawaiian man from the island of Lanaʻi who had grown up speaking English, learning about American history, and knowing little about his Indigenous language, culture, or political history. He was just learning about how Pacific peoples had navigated the ocean, guided by constellations, to find their islands. Hōkūleʻa was the first double-hulled voyaging canoe he had seen, a vessel built by Hawaiians eager to reconnect with knowledge that had been taken from them.

“This is how we got here,” Kahoʻohalahala thought as he gripped the rails of Hōkūleʻa that day and looked up at the sails. “I am part of these islands because I came on a canoe.”

As he inhaled the salty air and felt the immensity of the ocean stretching out around him, Kahoʻohalahala realized what it meant not just to be Hawaiian, but to be Indigenous to the Pacific, peoples whose lives and genealogies owe everything to the sea.

“That was a defining moment for me,” said Kahoʻohalahala, now 73.

Courtesy of Solomon Kahoʻohalahala

Patrick T. Fallon / AFP via Getty Images

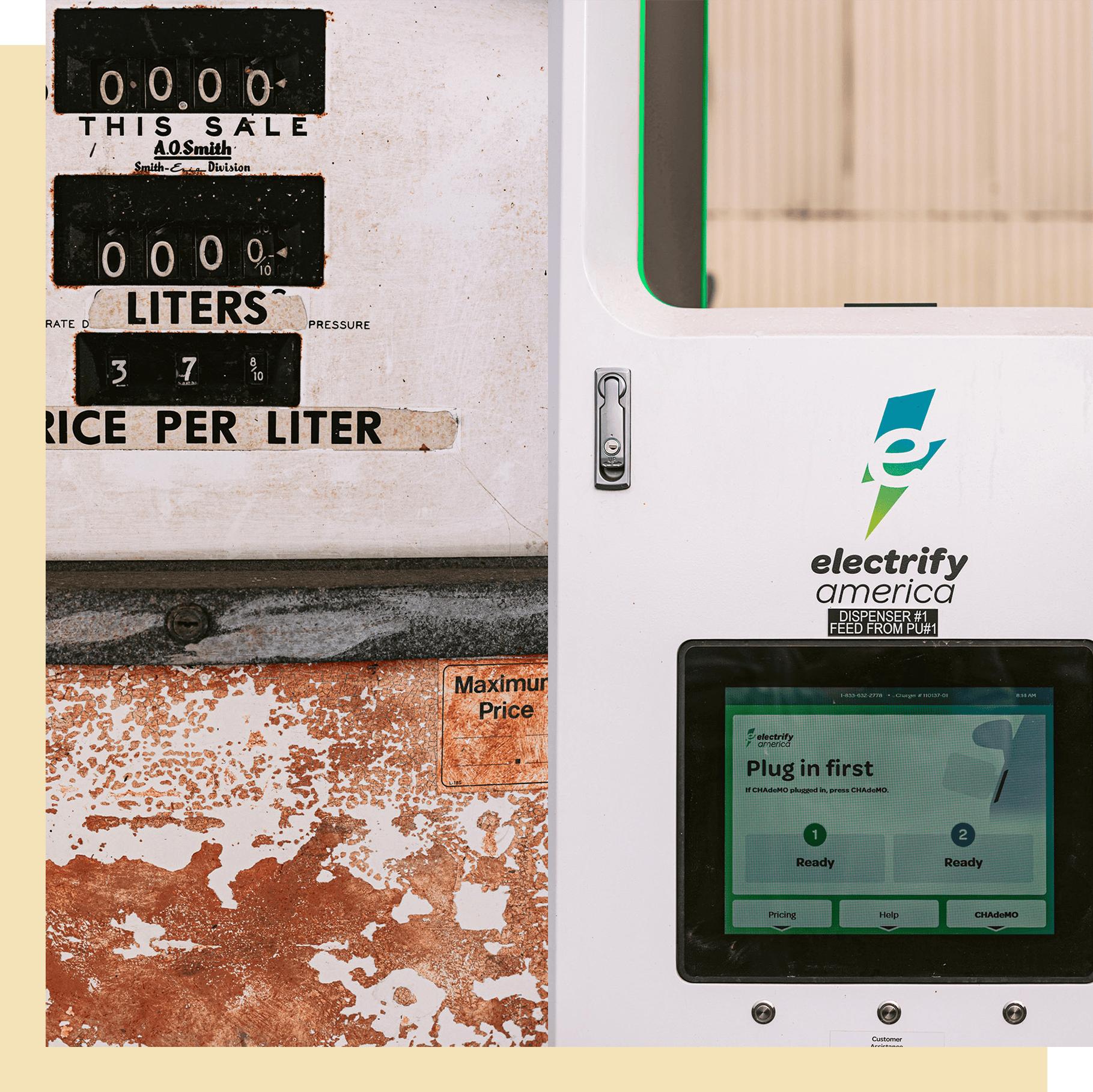

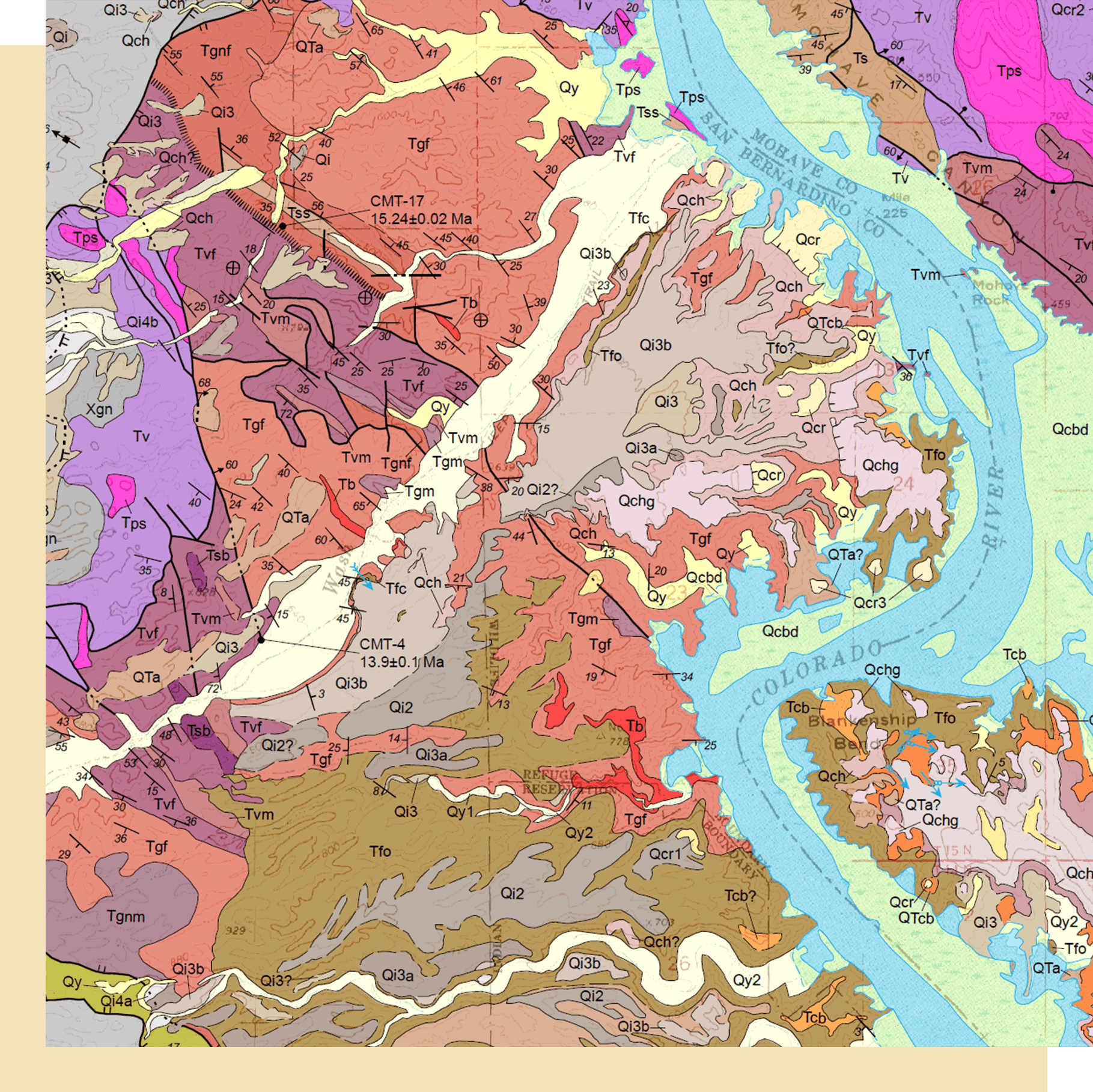

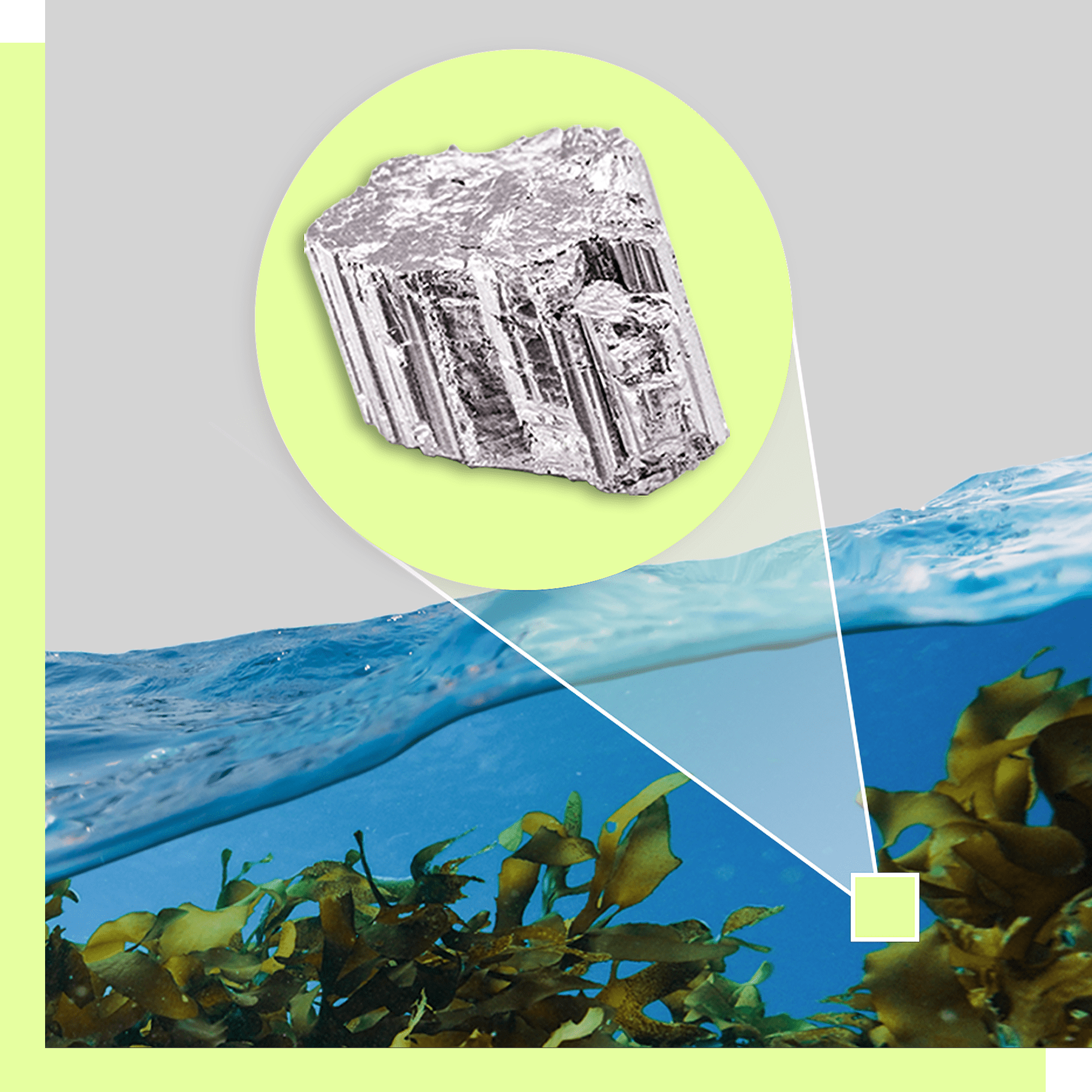

Today, the ocean that Kahoʻohalahala and so many other Indigenous peoples crossed, cared for, and survived on is on track to be mined for polymetallic nodules — potato-sized nodes that contain critical minerals necessary to power cell phones, electric vehicles, renewable energy, and weapons. The nodules are full of cobalt, nickel, copper, and other minerals, and were formed millimeter by millimeter over millions of years. Some are tens of millions of years old. The process to collect those nodules, called deep-sea mining, has been described as “a $20 trillion opportunity.” More than 500,000 square miles of ocean globally have been approved for mining — an area nearly twice the size of Texas — although only a fraction of that area actually has mineral deposits.

Mining for polymetallic nodules will require lowering massive tractors the size of houses more than 2 miles down to the seafloor where the vast majority of species are unknown and have yet to be named by humans. There, the machines will scrape the seabed, dredging up both sediment and nodules, carrying the latter up to the surface while releasing plumes of silt into the sea. Animals that aren’t crushed when the machines suck them up will likely be killed by the changing temperatures and atmospheric pressure that their bodies aren’t designed to exist in. Lifting the nodules to the surface could create sediment plumes that plunge downward, blanketing and smothering corals, sponges, and other animals that can’t escape. Depending on the depth where the plumes are released, their metallic contents might get absorbed by tuna fish and other sea creatures, contaminating essential food sources.

“There’s going to be damage at a very large scale,” said Jeffrey Drazen, an oceanographer at the University of Hawaiʻi who has received funding from a deep-sea mining company to research the environmental impacts of the practice. “It’s a matter of how much.”

The United Nations body in charge of overseeing mineral extraction from the international seafloor, known as the International Seabed Authority, or ISA, is in the midst of a yearslong process of finalizing regulations to allow countries and companies to excavate the deep sea. If passed, the rules could allow groups to tear the crusts off undersea mountains, rip nodules from the seafloor, and cut into chimney-like hydrothermal vents in the deepest, darkest parts of the ocean. Beyond the environmental harms, there are concerns that the process will violate the rights of Indigenous peoples who hold complex views and beliefs about the ocean and depend on it for their cultural, spiritual, and physical well-being and survival.

The current international rules that govern the high seas and allow countries to claim sections of them for mining date back to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a treaty that manages what happens in areas of oceans deemed outside national jurisdictions.

“The law of the sea basically colonized [Pacific peoples’] ocean,” said Frank Murphy, a resident of French Polynesia who along with his wife, Teurumereariki Hinano Murphy, has advocated with Kahoʻohalahala against seabed mining. “The law of the sea allowed the global community to say we have rights over this ocean including these high seas.”

Teurumereariki Hinano Murphy said visiting the headquarters of the International Seabed Authority in Jamaica made her realize how little control Pacific peoples have over what happens in their ocean.

“I realized that the future of our ocean is decided there,” she said, “far away from our people and our community, and without us being aware of what these nations are deciding for their benefit.”

Pallava Bagla / Corbis via Getty Images

Fifty years after his life-changing canoe voyage, Kahoʻohalahala is leading a group of Indigenous advocates, including the Murphys, to save the ocean from deep-sea mining. They are pushing the ISA to ensure that the regulations it finalizes explicitly state that any mining venture must obtain the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples ahead of commencing any commercial operations. It’s among several proposals that he and other advocates are fighting for, including ensuring that Indigenous peoples — whose territories are made up of far more water than land — are permitted full participation in discussions and decisions about deep-sea mining.

And the clock is ticking. The ISA has been working on seabed mining regulations since 2014, and in 2021, the country of Nauru formally requested that the ISA adopt regulations to govern seabed mining by triggering a treaty provision, which sets a two-year deadline for the authority to do so. If it doesn’t, Nauru’s plan to mine in the Clarion Kipperton Zone, nodule-rich international waters south of Hawaiʻi, will be “provisionally approved.” The regulations haven’t been finalized, and Nauru hasn’t moved ahead yet with mining, but an application could be submitted as soon as this year. Norway’s Parliament last year voted to open an area of its seabed for mining licenses before ditching the plan after heavy criticism, but countries are still snapping up exploratory licenses from the ISA to mine in international waters — with China in the lead. Meanwhile, the vacuum of knowledge about the seafloor has prompted hundreds of scientists and dozens of countries to call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until its potential environmental effects are better understood, including how the practice will impact fisheries that overlap with the underwater sites.

In the Pacific, Nauru isn’t the only country eyeing the new industry. Although many, such as Fiji and Palau, have called for a moratorium on mining, in Tonga and the Cook Islands Indigenous peoples are wrestling with the pressure to develop their economies and how doing so could irrevocably change their island homes that are already stressed by the effects of climate change.

“We’re experiencing this because we have already created an imbalance in our ecosystems, in our Earth, and now we are feeling the consequences of that,” Kahoʻohalahala said. “Do we continue to just move in that vein of continuous colonization, continuous extraction?”

Courtesy of Solomon Kahoʻohalahala

The Kumulipo is the Hawaiian chant that describes the creation of the world: “At the time that turned the heat of the Earth, at the time when the heavens turned and changed, at the time when the light of the sun was subdued to cause light to break forth.”

The song describes the ocean as the source of all living things, starting with sea creatures in the darkness and ending with an extensive Hawaiian genealogy connecting the people to the sea.

“We’re ocean people,” Kahoʻohalahala said. “We are related to the ocean because we are the seafarers and we came by way of canoe to inhabit the largest ocean on earth.”

Other Pacific peoples have similar creation stories, and the sacredness of the ocean isn’t limited to the birth of life, it also has a major role in death: “That’s where the soul of our ancestors, when they leave this world, they go into the deep,” said Teurumereariki Hinano Murphy from French Polynesia, an advocate alongside Kahoʻohalahala at the International Seabed Authority. Cecilio Raiukiulipiy, a traditional navigator from the Federated States of Micronesia, said until the 1970s, when Western influence changed burial practices, all of his relatives were laid to rest at sea. “Deep-sea mining, that’s like you’re digging up the grave of my ancestors,” he said.

Yet despite this cultural tie to the ocean, some Pacific countries like Nauru and the Cook Islands are at the forefront of exploring the potential of deep-sea mining.

“The greatest risk we face is not the potential environmental impacts of mineral recovery but the risk of inaction,” Nauru’s president David Adeang said at the U.N. General Assembly last fall. “There is a risk of failing to seize the opportunity to transform to renewable energy and decarbonize our planet.”

In the Cook Islands, Prime Minister Mark Brown, who is Māori, has described the pursuit of seabed mining within the islands’ surrounding waters as part of the country’s “journey of sovereign independence” and compared it to how Cook Islanders first navigated across the ocean using their knowledge of constellations and waves to find and settle islands like Rarotonga.

“We discovered the islands hundreds of years ago that today we call home. We had a capability that nobody else had,” he told a television reporter last year. “Today we choose now to take a journey that’s not across our ocean, but down into the deep ocean.”

Brown just signed a new agreement with China in February regarding seabed minerals, with details yet to be released. But he has promised that mining won’t proceed if it’s environmentally harmful. “If the extraction method is going to damage the ocean, then we’re not going to go ahead with it,” he said.

Drazen, the oceanographer from the University of Hawaiʻi, said some degree of environmental harm is guaranteed — the question is just how much. At the bottom of the sea, the ground has barely been disrupted for millions of years, and populations of sea creatures could take decades to recover. Heavy equipment is expected to hit and kill sea creatures upon impact. Among other ecological impacts of deep-sea mining, Drazen has studied how the plumes of sediment that mining is expected to generate could affect sea life closer to the surface, and suggested that mining companies consider releasing the plumes at lower depths to minimize impacts on fisheries.

And while Brown refers to seabed mining as “harvesting,” a commonly used descriptor by proponents of the practice, Drazen doesn’t think that term is accurate. Harvesting implies that nodules are a renewable resource, which they aren’t, he said.

Kahoʻohalahala thinks the reality is no Pacific nation is truly independent of one another: Any decision the Cook Islands makes, that Tonga makes, will affect the same ocean that also belongs to Hawaiʻi, to Guam, to Fiji, to Papua New Guinea, and beyond.

“Drawing circles around our islands to identify where our authority is doesn’t fit with the way we manage our places. There are no such divisions in the ocean that separate our responsibility,” Kahoʻohalahala said. “The ocean knows no barriers. Our resources move across the entirety of the ocean.”

Anita Hofschneider / Grist

Anita Hofschneider / Grist

In order for their sovereignty to be recognized internationally, Indigenous Pacific peoples had to adopt the nation-state structure created by imperial powers, conform to geographic boundaries carved by their colonizers, and enter a global economic order that prizes extractive industries. Pacific peoples were effectively told, “‘You have to look like us in order for us to recognize you,’” said Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, a political scientist at the University of Hawaiʻi from the Solomon Islands.

Establishing a nation-state might seem like liberation, but in other ways it was a reentry into a Western political and economic order defined by colonial powers. “States function in particular ways,” Kabutaulaka said. “They do not always function on behalf of Indigenous peoples.”

Many Pacific island nations achieved their current political statuses in the wave of decolonization that marked the early years of the United Nations. Back then, Western powers were shifting their imperial strategies away from expansive empires and toward specific strategic strongholds. In the decades since, island governments have sought to compete in the global economy as they watch their residents out-migrate for jobs, schools, and medical care they can’t get back home. But that’s often involved embracing foreign investors and industries that have left a litany of environmental and social problems in their wake.

“Independence is not decolonization,” Kabutaulaka said. “Inherently, the act of independence is an act of recolonizing.”

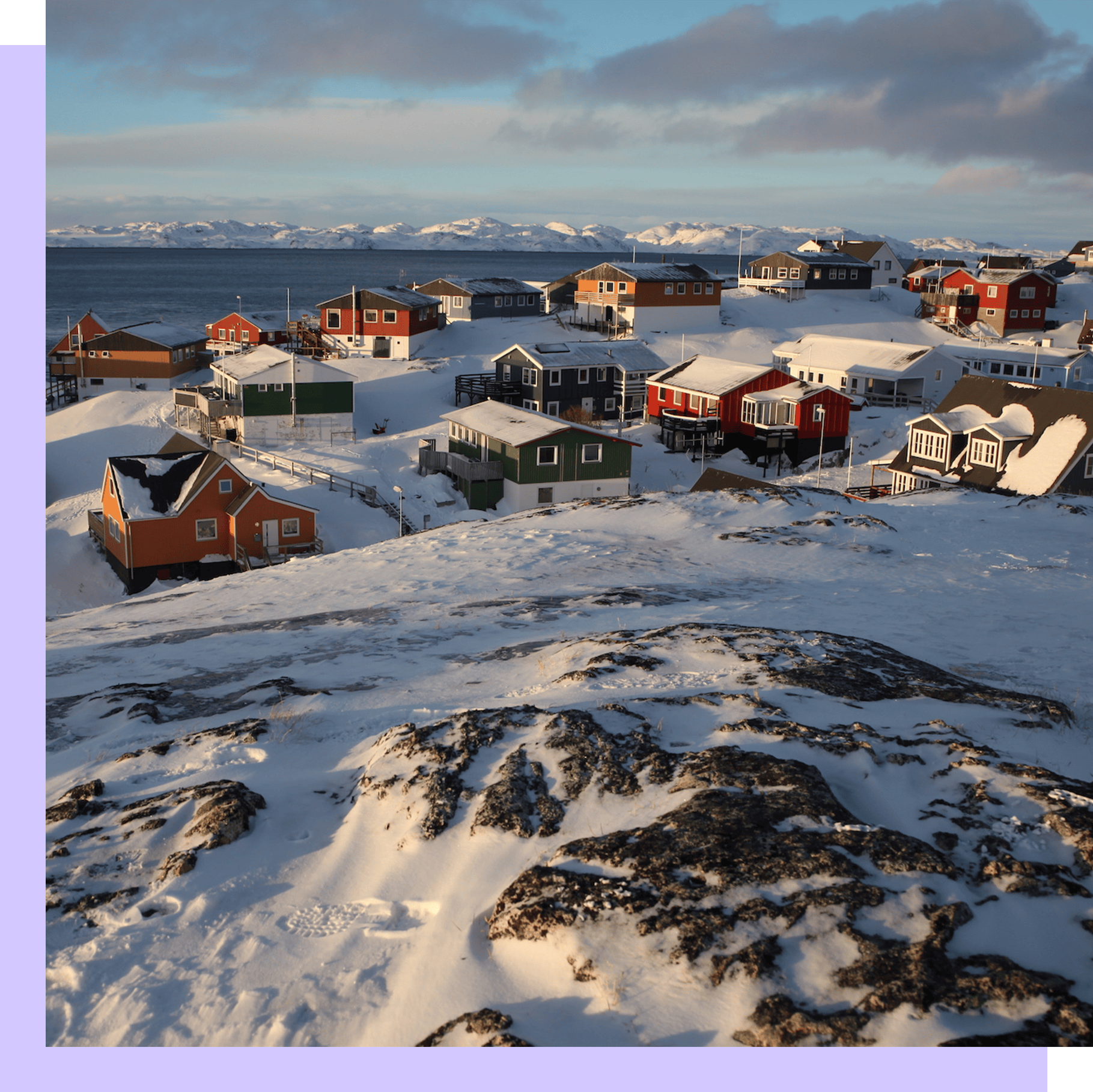

Nauru is an example: Under German rule, phosphate was discovered and mined on the island at the beginning of the 20th century. By the end of WWI, more than 600,000 tons of the mineral were taken and sold to make commercial fertilizer in other countries, with the Indigenous people of Nauru receiving far less than 1 percent of its value. The mining continued for another 50 years after ownership of the island was passed to Britain, New Zealand, and then Australia. After independence in 1968, the country continued phosphate mining. Now, 80 percent of its territory has been stripped, its dusty, rocky inland area is now uninhabitable and unable to be farmed.

Bettmann / Getty Images

The country has since shifted to selling fishing rights and detaining refugees and asylum-seekers for Australia. One analysis for The Metals Company suggested mining could bring in $7.2 billion in royalties for both Nauru and the International Seabed Authority, with more than $30 billion in net revenue.

In the Cook Islands, deep-sea revenue could be “transformational,” Prime Minister Mark Brown told reporters last year. A 2019 study suggested that deep-sea mining could be a multibillion dollar industry within the Cook Islands alone, which is estimated to have the worldʻs largest collection of manganese nodules within its surrounding waters. The country is home to fewer than 17,000 people who earn a median annual income of just over $10,000 U.S. dollars.

That kind of revenue would be alluring to most, but not to Teina Rongo, the first Cook Islander to get a doctorate in marine biology. “When I went abroad to study, seeing what’s happening in other parts of the Pacific, I started realizing the value of this way of life and what it brings to us,” he said.

Rongo grew up Rongo grew up fishing, farming, and speaking his Māori language. But when he visited New Zealand, also known by the Māori name Aotearoa, and Hawaiʻi, he saw how easily Indigenous peoples can be marginalized in their own lands. It’s something he’s already seeing in his home in Rarotonga in the Cook Islands: More westernization has meant more reliance on unhealthy imported foods and more people getting sick and moving away to access medical care like dialysis. More development has meant the paving over of wetlands that once held taro fields, and more industrial fishing has led to fewer and fewer fish for local fishers.

Rongo sees his people’s choice as a binary one: There is no deep-sea mining that doesnʻt disturb the seafloor, or harm its inhabitants. And while many see the Cook Islands’ quest for more revenue as a given, Rongo isn’t one of them.

“We don’t need to go in the same colonial pathway,” he said. “My concern is that if mining becomes a revenue generator for us, it’s just going to push us quicker in that direction. … And then we are going to lose who we are.”

Last summer, he flew to Honolulu with the Cook Islands delegation to a Pacific cultural festival. He and his fellow delegates later learned their journey was partially sponsored by the deep-sea mining industry. Over lunch in a mall in Waikiki, with luxury shops and a Tesla showroom, Rongo looked up at the towering buildings and said it felt like a warning of what Rarotonga could become if his people continued on a path to become a “developed” nation.

Imogen Ingram, another Cook Islands resident who helped Kahoʻohalahala petition the ISA to safeguard Indigenous heritage, is skeptical that mining will be as lucrative for her islands as many hope. Mining that far down in the ocean requires millions in upfront costs to pay for engineers and equipment. Companies like Tesla are creating electric vehicle batteries with little to no cobalt. The prices of metals have been volatile, with copper rising but manganese falling recently.

Rashid Sumaila, a professor of ocean economics at the University of British Columbia, said deep-sea mining might lead to short-term profits for mining companies and some financial benefits for countries like the Cook Islands, but the long-term costs are significant in part because of the risks of environmental harm that could lead to expensive litigation. In 2019, a failed deep-sea mining venture in Papua New Guinea’s waters saddled the country’s government with a $120 million debt when the mining company it had invested in, Nautilus Minerals, went bankrupt. One of Nautilus’ former leading investors is now the CEO of The Metals Company.

Under international law, Indigenous peoples have the right to free, prior, and informed consent for all projects within their territories. Their approval needs to be given freely before practices begin, and the people need to be fully aware of an activity’s implications.

But even if her Indigenous-led government consents to deep-sea mining, Ingram worries about whether the information her people are receiving about the industry is accurate and whether the leaders’ perspectives truly reflect the views of the people. For years, mining companies have been supporting community events and lobbying the country’s leaders. Ingram hears a lot about what benefits the mining will bring, but she doesn’t think there’s enough discussion in her community about its risks.

“Free, prior, and informed — it’s the ‘informed’ part that we’re not getting,” she said.

Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

On a recent day in February, Rongo held up a handful of soft, springy seaweed to 30 schoolchildren surrounding him on a beach in the Cook Islands. “Boodlea,” Rongo said, stating the seaweed’s scientific name and explaining it can be used for fertilizer. It’s part of his work leading a nonprofit helping connect Indigenous youth to traditional ecological knowledge before it’s lost.

“If our kids have no connection and relationship with their environment, they won’t value it,” Rongo said. “They’ll give it to anyone who comes here and wants to develop a mine or fish; they won’t care, they’ll just give it.”

He understands that some of his elders feel like they worked so hard to escape the hardships of traditional living and don’t want to go back, but he sees it as a climate solution: a way to lessen the insatiable consumerism and growth driving the climate crisis.

“If we live this life, we are actually adapting to climate change,” he said. “We live our simple life, we are doing our bit at the local level.”

Kahoʻohalahala feels the same. Since that first sail on Hōkūleʻa, he has traveled across Polynesia and to Micronesia and realized that the ocean unites far more than it divides Pacific peoples.

“In Oceania it took us a long time to understand that even though we’re colonized by different nations, we’re actually the same people and we have always been the same people,” he said. “All of us collectively as the people of Oceania, we have a connection to this ocean, which has inherent responsibility for its care.”

Rachel Reeves contributed reporting for this story.

:root {

–color-earth: #3c3830;

}

.mining-package__grid-header {

text-align: center;

margin-top: 8rem !important;

text-transform: uppercase;

}

.mining-package__grid {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: minmax(0, 1fr);

border-top: 1px solid var(–color-earth);

padding: 2rem 0;

margin-top: 2rem;

gap: 2rem;

max-width: none !important;

}

@media (width >= 40rem) {

.mining-package__grid {

grid-template-columns: repeat(2, minmax(0, 1fr));

}

}

@media (width >= 64rem) {

.mining-package__grid {

grid-template-columns: repeat(4, minmax(0, 1fr));

}

}

@media (width >= 64rem) {

.mining-package__grid {

grid-template-columns: repeat(4, minmax(0, 1fr));

}

.mining-package__story:nth-last-child(2) {

grid-column: 2 / span 1;

}

.mining-package__story:last-child {

grid-column: 3 / span 1;

}

}

@media (width >= 80rem) {

.mining-package__grid {

grid-template-columns: repeat(5, minmax(0, 1fr));

}

.mining-package__story:nth-last-child(2) {

grid-column: auto;

}

.mining-package__story:last-child {

grid-column: auto;

}

}

@media (min-width: 1440px) {

.mining-package__grid {

margin-left: calc(-300px – 3vw) !important;

margin-right: calc(-300px – 3vw) !important;

}

}

.mining-package__story {

display: flex;

flex-direction: column;

gap: 0.5rem;

}

.mining-package__story > p {

margin-top: 0;

}

.mining-package__story-header {

font-size: 1.5rem;

line-height: calc(2 / 1.5);

transition-property: opacity;

transition-timing-function: cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1);

transition-duration: 200ms;

}

.mining-package__story:hover .mining-package__story-header {

opacity: 0.75;

}

Read the full mining issue

A guide to the 4 minerals shaping the world’s energy future

Chile’s lithium boom promises jobs and money — but threatens a

critical water source

Most critical minerals are on Indigenous lands. Will miners respect

tribal sovereignty?

The energy transition could turn Greenland into a mining mecca. Would

it be for better or for worse?

Digging for minerals in the Pacific’s graveyard: the $20 trillion

fight over who controls the seabed

Mining is an environmental and human rights nightmare. Battery

recycling can ease that.

Tradeoffs of the green transition: Is mining critical minerals better

than extracting fossil fuels?

Why Biden and Trump both support this federal mineral mapping projecty

The weirdest ways scientists are mining for critical minerals, from

water to weeds

In the race to find critical minerals, there’s a ‘gold mine’ literally

at our shoreline

toolTips(‘.classtoolTips7′,’A lightweight, silvery-white alkali metal with properties that allow it to store large amounts of energy. Lithium is a key component of many batteries, including those that store renewable energy and power electric vehicles.‘); toolTips(‘.classtoolTips9′,’A conductive and heat-resistant metal that forms a key part of many battery cathodes, which allow electric charges to flow. It is used in the lithium-ion batteries that power many EVs as well as solar energy systems and wind turbine components.‘); toolTips(‘.classtoolTips10′,’A scarce blue metal that helps battery cathodes store large amounts of energy without overheating or collapsing. It is a key component of lithium-ion batteries. ‘); toolTips(‘.classtoolTips11′,’A lightweight, conductive, and ductile metal, copper is used to make most electrical transmission wires. Demand for the metal is projected to grow as the world adds renewable energy capacity.

‘);

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Digging for minerals in the Pacific’s graveyard: The $20 trillion fight over who controls the seabed on Mar 25, 2025.

Source link

Anita Hofschneider grist.org