1. Introduction

In ecological research, the spatial patterns of species distribution have long been a key topic for understanding biodiversity and ecosystem function [

1]. The global distribution of species is influenced not only by their biological characteristics but also by environmental factors [

1,

2]. Parasitism, as a critical component of ecosystem functioning, is one of the most common life strategies among the species existing on Earth [

3]. Parasites account for at least half of species diversity [

4], with common examples including endoparasites (such as tapeworms, bacteria, and viruses), ectoparasites (such as fleas, lice, and other insects), parasitic fungi, and parasitic plants [

5]. Among all parasitic organisms, the thousands of known parasitic plants occupy a particularly unique position [

6]. Not only do they have distinct ecological roles in influencing the growth and physiology of their host plants, but they also exemplify extreme evolutionary adaptations of parasitic organisms [

6]. For holoparasitic plants, such as the genus

Cuscuta (Solanales Juss. ex Bercht. & J. Presl; Convolvulaceae Juss.;

Cuscuta L.) [

7], their parasitic traits, ecological adaptability, and growth characteristics provide an ideal system for exploring the driving mechanisms of biological distribution. While studies have revealed the relationship between the host niche breadth and the distribution range of parasitic organisms (e.g., fleas and worms) [

8], such relationships remain largely enigmatic for parasitic plants. As a result, research on the relationships between the growth characteristics, ecological niches, and distribution patterns of parasitic plants is still relatively limited, particularly among closely related species, where comparative studies are notably scarce.

Cuscuta comprises four subgenera, among which species of the subg.

Grammica are almost entirely reliant on host plant resources for growth and reproduction [

9,

10]. These species exhibit a high degree of specificity in terms of ecological niche and environmental selection [

11,

12]. In this study, we focus on three species within China that have been clearly recorded:

Cuscuta chinensis Lam.,

Cuscuta campestris Yunck., and

Cuscuta australis R.Br. (

http://www.efloras.org), which are closely related species within subg.

Grammica. Generally, these species grow on their hosts without roots or leaves, with only stem tissue present prior to flowering and fruiting [

9]. As they are incapable of performing effective photosynthesis, they rely entirely on the host’s nutrients, leading to a significant reduction in global crop yields [

12,

13,

14], and are common and harmful in many regions globally, with a broad host range including plants from the Fabaceae, Asteraceae, and other plant families [

9]. Notably, these species not only reproduce on crops but also on weeds [

9,

10,

15]. Therefore, even in the absence of host crops, weeds can contribute to the soil seed bank of these parasitic plants, thereby infecting subsequent crops. To date, no effective methods have been developed to control subg.

Grammica species in agricultural settings, necessitating integrated management strategies [

15,

16]. Interestingly, these three species of subg.

Grammica share certain ecological and biogeographical similarities, providing a valuable research opportunity to explore the relationship between growth characteristics, ecological niches, and the global distribution patterns of parasitic species. Investigating the growth rates, niche breadths, and global distribution of these species will not only help to understand their adaptive evolutionary patterns but also shed light on how parasitic plants respond to global changes and environmental shifts.

In this study, we focus on four key variables: growth rate, niche breadth, the number of global occurrence points, and global distribution area. Growth rate is a critical indicator of a species’ potential for growth in a specific environment. For parasitic plants, it reflects the efficiency with which they rely on host plants and the physiological constraints on their growth [

17]. Niche breadth is an important ecological concept used to measure a species’ adaptability and the diversity of resources it utilizes, determining the range of environments to which the species can adapt [

18]. Finally, the number of global occurrence points is a significant reflection of a species’ distribution, often closely related to its adaptability and ecological expansion capacity [

19]. We hypothesize that these variables not only reflect the growth potential and ecological adaptability of each species but are also closely linked to their global distribution area.

The study organisms selected are three closely related holoparasitic plants:

C. chinensis,

C. campestris, and

C. australis. These species exhibit certain biological and ecological similarities, while also displaying significant differences in their global distribution ranges [

9]. The selection of these species provides a unique opportunity to examine whether growth rate, niche breadth, and the number of global occurrence points play significant roles in shaping their global distribution areas. We aim to reveal the potential impacts of these variables on species distribution and to explore their implications at both evolutionary and ecological levels.

Thus, the central question of this study is: For closely related holoparasitic plants in subg. Grammica, do growth rate, niche breadth, and the number of global occurrence points significantly influence their global distribution area? Based on this question, we mainly propose the following two hypotheses: (1) Growth rate is positively correlated with global distribution area; parasitic species with higher growth rates may be more capable of expanding across broader geographic regions; (2) niche breadth is positively correlated with global distribution area; parasitic species with greater ecological adaptability are likely to thrive and expand in a wider range of environments. By testing these hypotheses, we aim to provide new insights into the ecological mechanisms underlying the distribution of parasitic plants and offer valuable perspectives for species distribution studies in similar ecosystems.

4. Discussion

Parasites account for nearly half of the species diversity on Earth [

4], yet parasitology still appears to be plagued by data limitations that are almost insurmountable [

32,

33], leaving us with little understanding of their biogeography and global distribution patterns. Subg.

Grammica species, fully parasitic plants, serve as representatives of the extreme evolutionary adaptations found among thousands of parasitic plants. Their intrinsic growth patterns, niche characteristics, and distribution patterns provide an ideal system for studying the driving mechanisms behind the distribution of parasitic organisms. The key findings from this study’s experiments and analyses suggest that for subg.

Grammica species, there is a strong positive correlation between growth rate, niche breadth, number of global occurrence points, and global distribution area (

Figure 5). As growth rate increases, so do niche breadth, number of global occurrence points, and global distribution area. Notably, the correlation coefficient between growth rate and niche breadth is 0.994 (

Figure 5), suggesting that although parasitic plants interact with the environment through hosts as intermediaries, there may still be a strong relationship between the intrinsic growth characteristics of parasitic plants and their external ecological niche.

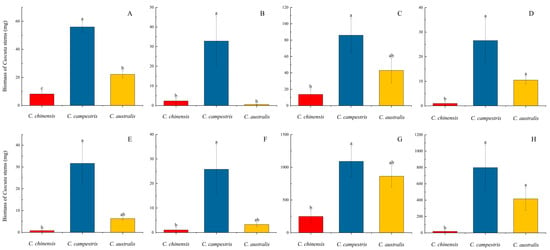

In addition,

C. campestris exhibits significantly higher growth rates on both non-native American and native hosts compared to

C. australis and

C. chinensis, and similar results can also be observed between

C. australis and

C. chinensis (

Figure 1). We believe that the growth performance of these three species of subg.

Grammica is likely regulated by their own genes and genetic traits. The entire experiment was conducted in a greenhouse with similar environmental conditions (see

Supplementary Section S1), thus allowing us to rule out the influence of environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and light conditions. Furthermore, when they parasitize non-native American hosts, they produce a higher biomass compared to when parasitizing native hosts (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Regarding this phenomenon, Hautier suggested that the growth rate and biomass of parasites increase with the host’s growth rate [

34]. Parasitic plants grow more vigorously on non-native hosts [

35], which can be explained by the fact that the host provides more resources [

36]. This view may explain some of the results observed in this study. However, when parasitizing

P. americana and

P. acinosa, we observed an inconsistent pattern (

Figure 3G,H). Within the same time frame,

P. acinosa produced significantly more biomass than

P. americana (

Figure 3G,H), yet the biomass of the parasitic plants was the opposite (

Figure 1G,H and

Figure 2D). Therefore, this study presents another intriguing hypothesis: when

C. campestris,

C. australis, and

C. chinensis parasitize non-native American hosts, they produce higher biomass compared to when parasitizing native hosts, possibly due to the long-term co-evolution between the parasitic species and their hosts [

37], which may result in better adaptation to the physiological characteristics and ecological behaviors of these hosts. There is evidence to suggest that the center of biodiversity for species of subg.

Grammica lies near Mexico in the Americas [

9,

10], and the distribution of closely related species to

C. campestris,

C. australis, and

C. chinensis is also largely restricted to the Americas [

10,

22]. Therefore, it is possible that these three species of subg.

Grammica have experienced a longer evolutionary history with American hosts. Of course, we still require more evidence to support this possibility.

As holoparasitic plants, subg.

Grammica species can reproduce asexually through their young shoots [

12,

15]. Seed germination typically requires seasonal variations in temperature and precipitation, with seeds generally germinating during the transition between spring and summer and growing alongside host species until autumn [

11,

16]. If the host is a perennial species that continues to grow through the winter, subg.

Grammica species are likely to persist on the host [

11,

16]. Therefore, this study selected 19 bioclimatic variables and altitude factors to estimate niche breadth, as temperature, precipitation, and their fluctuations are likely to be crucial (

Tables S5–S7) for

subg. Grammica species [

13]. During the PCA analysis, 20 principal component axes were generated, ordered by the variance they explained. Notably, the distribution range of species along different principal component axes is regulated by the contribution and significance of each axis to the species’ ecological niche characteristics, with the range gradually decreasing as the explained variance of the axes diminishes (

Table S11). The three subg.

Grammica species together explained all the variance across the 20 principal component axes. Therefore, unlike previous studies that selected the first two principal component axes to calculate niche breadth [

25], this study used the range of subg.

Grammica species across all principal component dimensions to specifically quantify and compare the niche breadth index for the three species.

In a recent study, Cebrián-Camisón revealed a positive correlation between the host species abundance of parasites and the number of occurrence sites [

38]. Species with broader ecological niches are typically able to survive under a wider range of environmental conditions and may have more occurrence sites [

39], which aligns with our findings for

C. campestris. Not only does

C. campestris have the broadest ecological niche (127.50) among the three species of subg.

Grammica, but it also has as many as 7450 occurrence points, suggesting that this species may have a high degree of adaptability and niche generalization on a global scale. Furthermore, the strong correlation between ecological niche breadth and global distribution area (

Figure 5) may, from the perspective of parasitology, further support the “niche breadth-distribution area” hypothesis in modern ecology [

40]. By utilizing a broader range of resources and maintaining viable populations under a wider set of conditions, species are expected to become more widespread, which will result in a positive correlation between ecological niche breadth and geographic range size [

41]. Furthermore, species with broader ecological niches are more likely to possess a wide range of resources within that niche [

40], such as host resources. It is noteworthy that during our attempt to gather host species data for the three species of subg.

Grammica worldwide, we found that

C. campestris has a host species richness far exceeding that of

C. australis and

C. chinensis. Although this aspect is not detailed in the main text, based on the available evidence, we can still hypothesize the following: For holoparasitic plants

C. chinensis,

C. campestris, and

C. australis, there appears to be a positive correlation between growth rate, host richness, and ecological niche breadth. We urge researchers in the relevant fields to devote more attention to the classification and identification of hosts for

Cuscuta L. species in future studies, to support more comprehensive and robust research.

Although the findings of this study provide evidence supporting the correlation between the growth rate, ecological niche breadth, number of occurrence points, and global distribution area of parasitic plants in subg.

Grammica, there are still several points that warrant further exploration. Firstly, our study is based on data from three species within the subg.

Grammica and does not delve into the growth performance differences of additional species within the subg.

Grammica across different ecosystems. For instance,

C. australis has a broad global distribution, but its growth rate may be significantly influenced by environmental conditions in various regions. Future research could involve selecting a broader range of species from the subg.

Grammica to participate in experimental analyses across different ecological regions, further investigating the relationship between the growth rate of parasitic plants and their ecological niche. Secondly, although we attempted to correct the distribution locations of the three species in the subg.

Grammica through field sampling and processed the global distribution data of subg.

Grammica species by removing duplicate records, outliers, and incorrect coordinates, the remaining distribution data may still be influenced by sampling efforts and researcher biases. To address this issue, future research should incorporate as much independent and reliable distribution information as possible to more accurately represent the true abundance of species and assist researchers in better estimating the species’ distribution ranges. Lastly, the measurement of ecological niche breadth in the dataset is based on the species’ distribution characteristics in geographical space, without fully considering other dimensions of the niche, such as the diversity of host resource utilization [

8]. Future studies will require more data on both abiotic and biotic factors to more precisely analyze the ecological relationships between species.

Specifically, the results of this study (

Figure 5) indicate that

C. chinensis exhibits a relatively low growth rate and a narrow ecological niche, with a more limited distribution range, suggesting that it may be a species more sensitive to environmental changes and with limited adaptability.

C. australis has a moderate growth rate, a larger niche breadth, and a wider distribution area than

C. chinensis, suggesting it is a species with moderate adaptability that can survive in a variety of environments.

C. campestris has a high growth rate, the largest niche breadth, and the widest distribution area, demonstrating that it is a species highly adaptable to environmental changes and capable of thriving in multiple ecosystems.

Exploring the relationship between the growth rate of species and their adaptability, ecological niche, and distribution range is one of the key topics in ecological research [

1,

2]. This study provides new insights into this subject through an analysis of species within the holoparasitic plant subg.

Grammica. Specifically, the strong correlation between the growth rate of parasitic plants and their global distribution area may reveal that the spatial distribution of parasitic organisms is influenced not only by local environmental factors but also by broader biogeographical forces. Moreover, the extensive ecological niche breadth of parasitic organisms offers a fresh perspective for understanding species’ performance across different ecosystems. In particular, when parasitic organisms exhibit a high growth rate, they may perform better in diverse environmental conditions, which is of significant theoretical importance for predicting their future adaptability on a global scale. By combining multiple ecological indicators, such as growth rate, ecological niche breadth, number of occurrence points, and global distribution area, this study presents a comprehensive profile of parasitic plant distribution and ecological adaptation, offering new approaches and methodologies for future research in ecology and biogeography.