The genus Asclepias L. was originally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who named it in honour of Asklepios (Ἀσκληπιός in Greek or Latin Aesculapius), the god of medicine and healing in ancient Greece, probably due to the plant’s long history of medicinal use [1]. Linnaeus described the common milkweed as A. syriaca L., based on the mistaken belief that this species, native to North America, originated from Syria [2]. The genus Asclepias L. s. str. (Apocynaceae, Asclepiadoideae) includes approximately 120 species native to North and South America and South Africa [3]. Most species are distributed in North America and the Caribbean, with ten species occurring in South America [4,5,6,7,8].

In Europe, the alien members of the genus Asclepias s. str. have been reported as alien naturalised species, namely, Asclepias curassavica L., A. incarnata L., A. syriaca L. [9,10], and A. speciosa Torr. [4], while, in several countries of Southern Europe, species of the closely related genus Gomphocarpus R. Br. have also been reported, e.g., Gomphocarpus fruticosus (L.) W.T.Aiton (Asclepias fruticosa L.) and Gomphocarpus physocarpus E.Mey. (Asclepias physocarpa (E.Mey.) Schltr.) [9,11,12,13]. Undoubtedly, A. syriaca is the most widespread and invasive species of this genus in South and Central European countries [14,15,16,17,18], while A. curassavica and A. incarnata have only been recorded as casual or locally naturalised aliens in different regions of Europe [9,19,20]. In Greece, A. curassavica with bright orange-red flowers, Gomphocarpus fruticosus, and G. physocarpus have been reported as established alien species [9] (http://www.alienplants.gr, accessed on 25 October 2024), while Asclepias speciosa Torr. has only recently been reported as a new alien plant in Northern Greece [21].

Asclepias speciosa shares several morphological traits with A. syriaca, the common milkweed, and it has been highlighted that the former may often be misidentified as the latter [4]. Since the introduction of A. syriaca in Europe in 1629 [22] for ornamental and various other purposes such as its potential for fibre and latex production, A. syriaca has become established in many regions of Europe, and it has spread increasingly over the last decades. It should be emphasised that the presence of A. speciosa in Europe was only indirectly revealed for the first time in southern parts of Lithuania [4] during an extensive assessment of A. syriaca in the country in relation to the implementation of the EU Regulation on Alien Invasive Species at the national scale in Lithuania. The reassessment of deposited herbarium specimens in Lithuania has revealed several cases of misidentified A. syriaca instead of A. speciosa. These herbarium studies have shown that A. speciosa was originally collected in Lithuania in 1962 [4]. Based on information from herbarium labels, the latter study has shown that A. speciosa occurred in the wild of Lithuania for almost 60 years prior to the official report, and, therefore, it can be considered a naturalised alien plant in Lithuania [4]. This species might have been introduced to Lithuania at the end of the 19th century or the beginning of the 20th century as an ornamental plant, perhaps was later cultivated by local people in their gardens or as a melliferous plant, and later escaped from cultivation [4]. The reproductive behaviour of A. speciosa is characterised by a high production of wind-dispersed seeds coupled with asexual reproduction by creeping lateral rhizomes, which allows the species to spread rapidly and establish colonies in new territories [23]. In its alien range in Europe, A. syriaca invades habitats that have already been degraded, at least to some extent, by anthropogenic disturbance [24]. It is a highly competitive alien species with a tall and shady habit, vegetative spread, drought tolerance, and allelopathic potential [22,25], which can actively modify its local environment as a transformer species [26,27,28]. Although such facts are not known to the same extent for the similar and closely related A. speciosa, both species share remarkable similarities in terms of plant habit, reproductive strategies, and ecology. The diversity of natural and anthropogenic habitats occupied by A. speciosa in its native (USA) and alien (Lithuania) ranges include several grassland habitat types and wetlands as well as road verges, disturbed lands, and arable lands, respectively, thus rendering it as a colonising grassland species and/or a weed of arable lands [4], thus posing a potential threat for agriculture. The latter rings a bell for the detailed study of A. speciosa at the earliest possible stages regarding its future naturalisation and invasion in Europe or species-specific management measures. In this context, Geographic Information Systems (GISs) have been widely applied in studies on invasive species. GIS is an effective supporting tool for the automated recognition of invasive species distributions through remote sensing [29], in predicting the potential spatial distribution of alien species [30], and for developing risk assessments on the potential impacts of invasive species on native species within their ecosystems [31]. Additionally, the ecological preferences of alien species can be retrieved through a GIS application in a similar fashion with cases of rare species threatened with extinction [32].

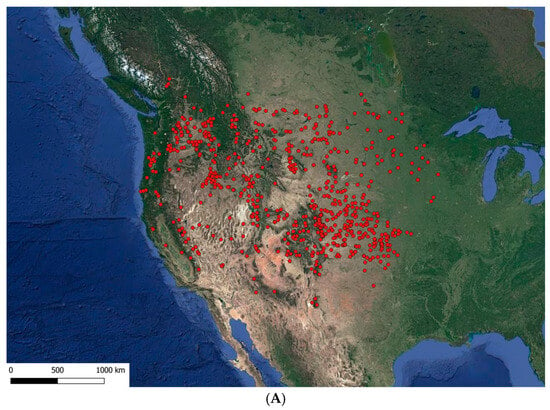

The present study focused on documenting the ecological traits of the pilot wild-growing population of A. speciosa (showy milkweed) recently reported for the first time from Northern Greece [21]; this population has been closely monitored over the last two years with observations preceding the latter study. The native range of A. speciosa includes parts of the western half of North America, from California to British Columbia and Central Canada and south to Texas. In its native range, A. speciosa is adapted to a wide range of soil types and moisture conditions, from riparian sites to dry sites [33]. However, little is known about the climatic preferences that shape or limit its natural distribution. Although A. speciosa was reported as an established alien plant in Europe only a few years ago [4] and as a new alien plant in Greece only a few months ago [21], knowledge about its climatic preferences and introduced population dynamics in Greece or Europe is still limited and its naturalisation and invasion status remain largely unknown. As Greece is only the second country, after Lithuania, to report the presence of A. speciosa [4], the present study aimed at documenting the presence of A. speciosa in the Greek territory as early and as completely as possible in terms of the first habitats occupied, the local climatic regimes tolerated, and the current reproductive potential enabled; such features may facilitate the first assessment of A. speciosa in terms of its current establishment, naturalisation, and invasion status [34]. The documentation provided in this study also represents a baseline assessment for future monitoring schemes and heralds early warning efforts aimed at preventing the potential invasion of this alien species in Greece and Europe.

Source link

Nikos Krigas www.mdpi.com