1. Introduction

The first law of thermodynamics, the energy conservation law, discusses the quantity of energy in a process. It states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, but it is a conserved quantity [

1], according to which it can only be transformed from one form to another. As an example, in a crop plant system, the incoming solar energy is converted into chemical energy during a photosynthesis process [

2]. Different models have been developed to study the energy balance in a crop plant system, taking into consideration the system boundary variation; most of the models have focused on the evaluation of sensible heat flux (H), latent heat flux (LE), and soil conduction (G) [

3,

4], usually derived from eddy covariance (EC) flux measurement towers [

5], which is considered the most direct method to monitor energy fluxes. On the other hand, the second law of thermodynamics describes the changes in the quality of energy, otherwise known as exergy, in a process. It is the driving force behind living systems and self-organization; exergy destruction is directly proportional to entropy production, according to the Gouy–Stodola theorem [

1]. The second law of thermodynamics explains the relationship between temperature and entropy; when a system is involved in an irreversible process, entropy will be produced, and exergy will be destroyed.

Entropy production is an implicit form of exergy analysis, according to the Gouy–Stodola theorem, (

) [

6,

7], where

is the level of exergy destruction,

is the temperature of the environment, and

is the amount of entropy production. Exergy is used in this regard as opposed to energy and entropy due to its three main properties: context-sensitive, universal, and not conserved property. First, exergy is context-sensitive because it is formulated with respect to a reference environment [

8,

9,

10]. In addition, when a system is subject to a thermodynamic equilibrium with its surroundings, it will have zero exergy [

11]. Second, exergy is a universal property, according to which all thermodynamic systems are compared based on their exergy content [

7]. Third, unlike energy, it cannot be created or conserved, but only destroyed, during an irreversible process [

8,

12,

13]. Due to its properties, exergy is used as a decision-making and optimization tool in many engineering applications, such as power plant design and operation specifications [

14], and it is also used in many non-engineering applications, including ecology [

15,

16,

17], life cycle assessments [

18,

19], resource accounting [

8,

20,

21], biology, sustainability [

15,

16,

22], and as a health assessment tool in terms of an ecosystem [

23]. Exergy is preferred over entropy because it has the same units of measurement (e.g., kJ) as the units of entropy (e.g., kJ/K). For example, exergy can be considered the ability to lift a weight. It is fundamental to the exergy destruction principle for ecosystems [

15,

16,

17,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], and it has a well-defined maximum compared to entropy production.

The main difference between exergy and Gibbs free energy lies in their reference frameworks; exergy quantifies the amount of work an energy carrier can perform relative to its surroundings rather than describing an isobaric process involving the energy carrier and a reference state [

32]. Gibbs free energy represents the maximum amount of work that a system can perform under constant temperature and pressure conditions, which has wide applications in engineering, particularly in terms of investigating the relevant chemical reaction and phase change-related problems [

33]. Exergy represents the theoretical maximum work potential within a given environment rather than the actual work achievable with the existing technology.

Many researchers have made significant contributions in the field of exergy when applied to ecological and agricultural systems. Szargut [

34] proposed integrating exergy analysis with ecological concepts to investigate the interactions between human activities and natural systems. In addition, the cumulative exergy consumption (CExC) of non-renewable natural resources was introduced, which was utilized to assess various energy limitations in the crop production process [

35]. It is defined as the total exergy of all the resources utilized and consumed throughout the supply chain of a specified product or process [

36]. Furthermore, Szargut [

37] applied exergy principles to agricultural systems to evaluate the energy efficiency of crop production. His work focused on analyzing the balance between inputs (e.g., sunlight, fertilizers, water) and outputs (e.g., biomass, yield) to identify opportunities for crop yield optimization. Orrego et al. [

38] applied exergy analysis to complex systems, such as biological systems, which included assessing exergy destruction in regard to living organisms. It was found that the exergetic efficiency of plant vegetation is notably low [

38]. Many researchers have adopted Szargut’s methodology in calculating the physical and chemical exergy of crop plant systems. Furthermore, Pimentel focused on the input–output analysis of agricultural production systems, with the aim of demonstrating its ongoing relevance to address complex environmental issues [

39], including soil erosion, the loss of biodiversity, and biofuel and biomass energy-related problems. Pimentel and Patzek [

40] suggested that living systems can sustain themselves and reproduce if they successfully acquire what they define as “energy input” (exergy within a well-defined system) and eliminate what they classify as “waste” (degraded energy). This concept was further developed and refined by the Prigogine school of thought [

41,

42,

43] through advancement in non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Righetto and Mady [

44] conducted an exergy analysis of sun–plant interactions in sugarcane cultivation using mathematical models to estimate plant production and exergy flows while evaluating photosynthetic efficiency. Their findings revealed that exergy efficiency varies significantly with seasonal changes. Jekayinfa et al. [

45] investigated the exergy analysis of soybean production in Nigeria. It was found that the exergy-to-energy ratio of certain inputs, such as potassium and phosphorus, exceeded unity. Nikkhah et al. [

46] explored the impact of variety selection on the exergy flow within a paddy rice production system. Nine varieties of rice were assessed in Italy using the cumulative exergy analysis method. It was found that fossil fuels and chemical fertilizer accounted for the highest consumption relative to total energy consumption across all varieties.

Two hypotheses have been developed to detect crop stress at early growth stages before any visible signs appear on the plant surface [

47,

48,

49]. The first hypothesis posits that crops exhibiting greater growth and higher yield will have lower daytime surface temperatures compared to less developed crops. The second hypothesis asserts that stressed crops will have higher surface temperatures during the day compared to less stressed crops and lower surface temperatures at night to maintain the net energy balance assumption. The exergy destruction principle (EDP) was used as a theoretical framework to explain the anticipated inverse relationship between crop surface temperature and crop stress [

48]. Thermal remote sensing was employed through crop surface temperature measurements and spectral emissivity calculations to test the two hypotheses under greenhouse and variable field conditions. The results confirmed at a 0.05 significance level that stressed and less developed crops have higher surface temperatures during the day compared to less stressed and more developed crops. Therefore, it is important to investigate energy and exergy models using the two main thermodynamics principles (i.e., first and second laws) and apply them to a crop plant system—corn, for instance, as discussed in this paper. According to the first law of thermodynamics, cooler surfaces emit less radiation at a lower exergy level into the atmosphere compared to warmer surfaces [

17,

24,

26]. Consequently, a system will gain more exergy, as suggested by the second law of thermodynamics. Thus, crop surface temperature reflects the efficiency of the first and second laws of thermodynamics. This paper focuses on energy and exergy balance models, employing different sets of assumptions to simplify the equations and analyze various input and output terms (e.g., fertilizer input, soil conduction flux, water transpiration, biomass output, etc.) to identify the largest contributing factors and confirm the use of surface temperature as an indicator for crop stress detection from an exergy balance perspective.

A crop plant system can be modeled as a black box with input and output energy flow from an engineering thermodynamic perspective [

47,

48,

49], where all physiological processes and mechanisms involved in regulating crop surface temperature, including transpiration, evapotranspiration, stomatal conductance, and photosynthesis, are considered [

48]. Variations in crop surface temperature, as predicted by the exergy destruction principle (EDP), are primarily influenced by the development processes occurring during the early growth stages of corn plants [

47,

48]. Environmental conditions must remain consistent across systems when comparing crop plants supplied with different nutrient levels using the exergy destruction principle. This means nutrient availability is treated as an internal factor within the “black box”. This approach allows for an EDP-consistent comparison between crops supplied with varying nutrient levels [

47,

48,

49]. The exergy destruction principle (EDP) operates as a “black box” model that disregards internal system mechanisms, such as respiration, and focuses exclusively on energy flow at the system boundary. In the context of non-equilibrium thermodynamics for complex systems, such as crop–plant systems or ecosystems, exergy serves as a measure of the deviation between the system and its environment from thermodynamic equilibrium, which is driven by an externally applied gradient such as temperature or pressure. Consequently, both the system and its environment must be well defined. Exergy is a valuable tool for analyzing non-equilibrium thermodynamic systems; higher exergy levels indicate a greater deviation from equilibrium. The exergy destruction principle, as defined by James Kay [

17,

26], states “A system subjected to an external flow of exergy will be displaced from its equilibrium state. In response, the system will reorganize itself to degrade exergy as effectively as possible under the given conditions, thereby minimizing the extent of its deviation from thermodynamic equilibrium. Moreover, the further the system is displaced from equilibrium, the greater the number of organizational (i.e., dissipative) opportunities that become available, which result in increased efficiency in the amount of exergy being destroyed”. The further the system is displaced from its equilibrium state, the greater the destruction of exergy and the production of entropy, which means that more work is needed to maintain the system in its non-equilibrium state [

15,

48]. The exergy destruction principle (EDP) hypothesis states that ecosystem development is related to optimizing the available work required for organization, structure, function, and survival, thereby enhancing the ecosystem’s capacity to destroy the incoming solar exergy. Ecosystems are complex, non-equilibrium, self-organizing, dissipative thermodynamic systems that are open to energy and mass flows, maintaining their organization and structure through continuous energy dissipation. As ecosystems evolve and mature, their total energy dissipation and utilization of available exergy increase, leading to the development of more complex structures with greater diversity [

17,

26]. This development allows ecosystems to adapt to their environment while enhancing their capacity to capture and utilize solar exergy from the incoming radiation to sustain their organization. The greater the exergy being captured, the stronger the ecosystem’s ability to support organizational processes. Consequently, the progression of ecosystem development is quantified by its rate of exergy utilization [

17,

26]. Exergy, unlike entropy, indicates how far from equilibrium a system is, the magnitude of the gradients, and the potential of the system to perform useful work [

15,

16].

For more details on how this EDP principle is applied to a crop plant system, please refer to our longer work in [

47,

48,

49]. Conducting energy and exergy analyses for a crop plant involves evaluating the energy and exergy flows within the various processes associated with cultivation, harvesting, and processing. For energy input analysis it is important to consider the amount of energy received from the sun during the growth period, which is crucial for photosynthesis. In addition, it is important to include the energy used in production, transportation, and application of fertilizers, as well as the energy required for irrigation. For the energy output analysis, it is essential to include the biomass which evaluates the energy content of the harvested plant considering both grain and plant residues. On the other hand, exergy is a measure of energy quality, defined as the maximum useful work achievable relative to the dead state [

24]. Exergy analysis considers not only the quality of energy but also the irreversibilities in different processes. For a crop plant, it is important to evaluate the exergy content of input and output flows through the system boundary, including solar, water, and nutrient exergy as inputs, and biomass as the output. Solar, water, and nutrient exergy as input, and biomass as output. Exergy analyses are vital for decision-making tools for analyzing, comparing, and simulating different thermal systems. The objective of this paper is to investigate the energy and exergy flows in a crop plant system to identify the dominant flows and parameters (e.g., temperature) affecting crop plant development. Additionally, several opportunities for developing the proposed exergy analysis are explored.

Crop Surface Temperature Measurement Considerations

The two hypotheses developed to detect crop stress at early growth stages [

47,

48,

49] were tested under greenhouse and field conditions. For field experiments, soil nitrate samples were collected from a depth of 30 cm multiple times: before planting and after harvesting the field to investigate the residual nitrogen content in the soil from the previous year. The same plots were used to examine the variation in nitrate levels in the soil. Five cores per plot were collected and combined. A non-significant difference in soil nitrate was observed among different nitrogen treatments within the field before fertilizer application each year; this finding implies that the amount of nitrogen applied in the previous year does not impact soil nitrate levels in the subsequent year. For greenhouse experiments, soil nitrate content was measured using a colorimeter (Smart 3 Soil, LaMott, MD, USA), which showed that soil nitrate content increases with nitrogen rate supply.

In regard to water content, the volumetric water content (i.e., the ratio of the water volume to soil volume) was measured across various plots within the field using an EC5 soil moisture sensor (Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA), which was installed at a depth of 10 cm below the ground surface. Corn plants were monitored for water stress conditions throughout the growing seasons of 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019 with concurrent measurements of soil volumetric water content and precipitation rates [

47,

48]. For example, in 2018, the volumetric water content for plots receiving 0 and 188 kg N ha

−1 was 18.46 ± 0.058% and 16.33 ± 0.038% (m

3 m

−3), respectively, based on 10-day averages across four plots per nitrogen rate [

48]. These values fall within the field capacity range of 22% to 28% for silt clay loam soil [

50]. Additionally, the absence of visible wilting in the plants suggests that corn plants did not experience significant water stress [

47].

The measured crop surface temperatures were corrected for meteorological conditions on different days, as variations in air temperature affect the sensitivity of crop surface temperature measurements. The following equation was used for the crop surface temperature correction:

where Tc is the canopy temperature (°C), Ta is the air temperature (°C), and Ta_mean is the mean air temperature (°C).

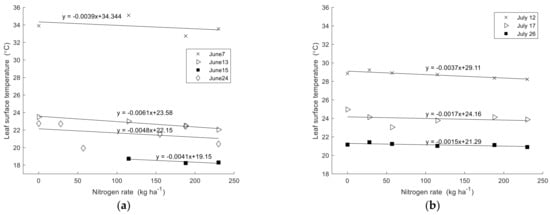

It was observed that the corn surface temperature decreased with increasing nitrogen application rates. A consistent, statistically significant (

p-value < 0.05) negative correlation was identified between the crop surface temperature and applied nitrogen rate. However, surface temperature measurements showed variability due to external and weather-dependent factors that influence crop surface temperature.

Figure 1 below summarizes the mean surface temperature as influenced by the nitrogen application rate during June and July 2017. The regression analysis consistently identified a negative slope [

47,

48].

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of various input variables on the output (i.e., crop surface temperature). The findings indicated that the non-stress-related variables such as variations in solar irradiance, air temperature (T

air), soil temperature (T

soil), vapor pressure deficit (VPD), soil moisture (Soil

moist), relative humidity (RH), wind speed (V), time of the day (t), cloud cover (CC), crop genetics, leaf angle (θ), leaf emissivity (ε), and sensor view angle require further control or compensation through conditional sampling. This approach would enhance confidence in the results when investigating the relationship between crop stress and crop surface temperature under variable conditions [

48].

4. Discussion

This study investigates energy and exergy flows in a crop plant system to identify the dominant flows affecting crop plant health and development. After conducting an energy balance analysis, it was found that radiation and transpiration dominate all other energy input and output flow terms. For the exergy balance, it was found that solar exergy is the dominant factor among all exergy input and output flow terms with the majority of solar exergy either being utilized or destroyed by the system through various processes, including photosynthesis and transpiration.

Exergy serves as an ecological indicator to evaluate ecosystem development, complexity, and integrity [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The incoming solar exergy is significantly greater in magnitude compared to the amount of exergy consumed by human activities. The sun provides approximately 13,000 times more exergy than what is utilized by humanity [

8,

20,

21]. Solar exergy reaching the Earth’s surface sustains life on Earth by driving photosynthesis in crop plant systems, which converts solar energy into chemical energy [

48]. Ecosystems evolve to enhance their capacity to survive in the environment by efficiently utilizing solar exergy from incoming radiation to sustain their internal organization. The greater the amount of solar exergy an ecosystem captures, the higher its capability to support organizational and survival functions [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Thus, ecosystem development can be assessed by measuring its rate of solar exergy utilization [

48,

49].

The exergy destruction principle is used to explain the relationship between crop surface temperature and crop stress. During the day, the solar exergy input significantly exceeds the exergy output [

48,

49], demonstrating a direct relationship between solar exergy and crop surface temperature as presented in

Section 2.4.1. In this context, solar exergy can be altered solely by modifying the surface temperature, assuming a constant solar temperature. It was found that the available solar exergy to a crop plant system is maximized at lower surface temperatures based on the exergy analysis for a crop plant system [

48,

49]. Therefore, a crop system’s health and development can be assessed using its surface temperature. This study highlights the significance of using crop surface temperature as an indicator of crop stress, as explained through an engineering thermodynamic principle (i.e., the exergy destruction principle). According to this principle (EDP), more developed and complex ecosystems, including crop plant system, exhibit lower surface temperatures during the day compared to less developed ecosystems [

30,

31,

47,

48,

49]. Crop plant systems evolve to enhance their efficiency in exergy degradation, as shown by surface temperature measurements, which are consistent with the predictions of the exergy destruction principle [

47,

48,

49]. Exergy destruction within a crop plant system is determined by the difference between incoming and outgoing exergy flows. The exergy of incoming radiation is the dominant component of these flows. Assuming that a crop plant system receives the same amount of incoming solar energy (i.e., under identical field conditions and environmental parameters), less stressed and more developed crops will emit energy at a lower exergy level, resulting in a lower surface temperature compared to stressed and less developed crops. Therefore, crop surface temperature can be utilized as a primary indicator of the exergy available to a crop plant system.