1. Introduction

In 2019, Brazil generated approximately 73 million tons of solid waste, with around 45% originating from agricultural, industrial, and urban activities with potential for use as fertilizers [

1]. Many organic residues (ORs), rich in proteins, amino acids, and labile nitrogen (N) forms, can serve as valuable N sources for crops [

2,

3]. Recycling and the use of N from postharvest waste, fishing industry byproducts, and animal manures are essential steps to reduce Brazil’s reliance on imported N fertilizers [

4]. However, organic waste must undergo processing for chemical stabilization and sanitation before adding it to agricultural soils. Pyrolysis is an efficient and fast process that stabilizes N in the final biochar, changes the waste chemical composition, and enhances carbon (C) persistence in the soil–plant system [

4,

5]. However, depending on the intensity of charring conditions, a portion of the N in feedstocks is lost during the pyrolysis process [

4,

6,

7]. During pyrolysis, N is retained in aromatic, ammonium-N forms, or within the sorptive complex or micropores of the biochar, potentially reducing N losses through leaching and volatilization. However, biochar can also increase soil nitrification rates and pH, which may lead to increased soil nitrate leaching [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Biochar contains both mineral and organic N; although, pyrolysis typically reduces the overall N retention in the final product [

13]. The N content, N chemical species, and aromatic character of biochar strongly depend on the pyrolysis temperature [

4,

10]. Biochars produced at temperatures above 450 °C contain chemically stable N forms resistant to soil mineralization due to the high energy required by soil microbes to decompose aromatic N structures [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Conversely, feedstocks high in N and pyrolyzed at temperatures below 350 °C yield biochars with more readily mineralizable N than those formulated at higher temperatures [

4]. Nonetheless, higher pyrolysis temperatures result in biochars with fewer labile N forms, and their high C/N ratio can lead to increased soil N immobilization rather than the release of N for crop nutrition [

13,

14,

17].

Maize is one of the primary crops cultivated in Brazil’s Cerrado region, where the soils are characterized by high exchangeable aluminum (Al), a strong capacity to fix phosphate, and low to moderate soil organic matter (SOM) levels [

18,

19]. Urea, monoammonium phosphate (MAP), and ammonium sulfate are the primary N fertilizers used in Brazil for maize cultivation. Nitrogen from mineral soluble fertilizers is prone to losses through runoff, leaching, ammonia volatilization, denitrification, and immobilization by soil biota or within SOM [

20,

21,

22]. Ammonium nitrate, increasingly used as a topdressing N source for maize, positively impacts grain yield by supplying both ammonium and nitrate in balanced levels, which enhance maize nutrition and growth [

9]. The relative proportion of nitrate (NO

3−) and ammonium (NH

4+) supplied to maize plants depends on factors such as soil type, pH, plant growth stage, soil nitrification rates, and N sources used to nourish crops [

9,

23]. In Oxisols, N availability is governed by SOM content and mineralization rates, which regulate plant N acquisition [

20,

24]. Due to the low residual N levels in tropical soils, annual applications of mineral N fertilizers are crucial for increasing maize yields [

25,

26]. Therefore, the N rate, source, and use efficiency are critical for nourishing and promoting maximum maize growth while minimizing N losses through leaching, volatilization, and denitrification [

27].

Biochar influences the dynamics and proportions of N forms in soil, affecting soil pH, organic matter decomposition, nitrification, denitrification, and volatilization process rates [

10]. The C/N ratio of biochar directly affects its decomposition rates as C:N ratios exceeding 30:1 promote temporary N immobilization [

28,

29]. Supplementary mineral N fertilizers may be required where biochar-induced N immobilization outweighs mineralization. According to Mota and Silva [

30], biochar–N composites, particularly those formulated with DAP, were as effective as urea in promoting plentiful maize growth. Conversely, the maize dry matter reduced when plants were only fertilized with raw biochars, showing that N from some biochars was insufficient to meet maize’s N requirement. In the study of Castejon-del Pino et al. [

31], biochar N-doping with urea increased the water-soluble fraction of N up to 14.5% of the total N, indicating that biochar N-based fertilizers can progressively supply N to plants, acting as true slow-release fertilizers. In tropical soils, the increase (12%) of N use efficiency and corn yield (26%) of plants fertilized with N-doped biochars were attributed to the gradual release of N from the biochar N-enriched fertilizers [

32].

In addition, many studies on the interaction between N and biochar have focused on its interaction with urea and/or sources containing the nutrient in only one form (nitrate or ammonium), with few addressing its application as ammonium nitrate, which provides both nitrate and ammonium forms [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Due to differences in charge, molecular size, and soil interactions, the simultaneous application of both N forms may interact differently compared to the application of a single N form [

8,

10,

12]. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the dynamics of these N sources when combined with biochar, which is an effect that is also highly dependent on the soil type used.

Preliminary studies have shown that sources such as sunflower cake, chicken manure, and shrimp carcass have high potential as nitrogen sources for plants [

4,

37]. However, biochars derived from bamboo have a high C:N ratio and contain more recalcitrant carbon, which can immobilize nitrogen in the soil, affecting both native soil N and that from mineral fertilizers [

4]. Additionally, due to differences in the properties of these biochars, they may exhibit distinct mechanisms influencing nitrogen mineralization or immobilization in the soil.

In this context, this study aimed to: (i) assess the capacity of raw feedstocks and their derived biochars, with or without ammonium nitrate, to supply N to maize plants; (ii) evaluate the interaction of soil type and N sources on N availability in solution and whole Oxisols; (iii) investigate the need for supplementary N from ammonium nitrate when tropical soils are treated with contrasting biochars; and (iv) determine residual soluble N in Oxisols following maize cultivation. We hypothesize that biochars may act synergistically with mineral N fertilizers or, depending on the biochar type, conversely, immobilize N, potentially limiting maize growth when readily available N is not added to Oxisol. Therefore, it is critical to investigate whether the N supplied by organic residues, biochars (alone or in combination with ammonium nitrate), and native SOM N can sufficiently support maize growth under greenhouse conditions in tropical soils with varying textures and organic matter content.

4. Discussion

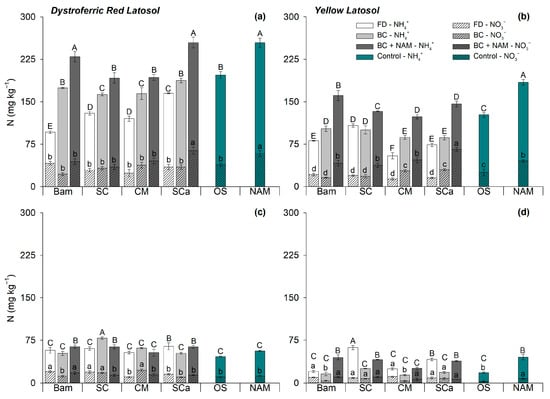

The use of biochars combined with ammonium nitrate altered soil nitrogen (N) dynamics by influencing its availability in the whole soil and soil solution, as well as N uptake by plants, in a soil type-dependent manner. The availability of mineral N in the soil varies depending on the N source, with higher mineral N levels observed in soils treated with biochars compared to those in which plants were nourished with N from the biochar precursor feedstock. The addition of 300 mg kg−1 N as ammonium nitrate significantly increases available N in the soil compared to other treatments.

In mineral soluble fertilizers, N is readily available, whereas the N chemical species in biochar depend on the feedstock N content and the intensity of charring conditions [

4,

31]. In this study, only a few N sources exhibited mineral N availability in the whole soil comparable to that of ammonium nitrate (AN). In the whole soil, ammonium-N predominates over nitrate-N, particularly in biochar and biochar mixed with AN. Mixing AN with biochar results in lower mineral N availability than the exclusive use of AN, suggesting that part of the mineral N may be immobilized within the biochar matrix, native soil organic matter, or soil biota. This interaction between applied nitrogen and biochar has also been demonstrated in a study using biochars derived from coffee husk and chicken manure, indicating that the main mechanisms involved in this interaction and N retention include adsorption through electrostatic bonds at the CEC, the formation of N precipitates such as struvite, and physical adsorption of ammonium-N in biochar pores [

37]. In addition to low N content, biochars exhibit a high C/N ratio. Consequently, depending on the application rate and water-soluble C content, these materials are prone to immobilizing mineral N in soils [

9,

10]. Over time, the combined use of some biochars with AN increases nitrate-N availability in Oxisol solutions, with nitrate-N levels from AN exceeding those found in soils treated with most biochars and their pristine feedstocks.

Biochar is believed to increase soil nitrification rates, particularly in low-fertility soils, which is partially explained by biochar’s liming effect and its ability to influence the activity and structure of soil nitrifying bacteria [

47]. In this study, ammonium-N prevailed over nitrate-N in whole Oxisols; although, nitrate-N levels in soils fertilized with biochar combined with AN were higher than in soils treated with other N sources, particularly in soil solution. Biochar can act as an electron shuttle, potentially promoting dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium, thereby contributing to higher ammonium levels, as observed in our study [

48].

The high levels of nitrate in soil solution in the beginning of maize cultivation are concerning, as nitrogen in the ammonium-N form is much less susceptible to loss than nitrate-N. The high levels of nitrate in the soil solution are probably explained by AN itself rather than the biochar effect on nitrification. While NH

4+ can be adsorbed by soil colloids with minimal downward movement, NO

3− is not easily adsorbed, remains in soil solution, and can be leached into deeper soil layers, potentially contaminating groundwater [

49,

50].

Native organic soil matter plays a crucial role in controlling the availability of N in the investigated Oxisols. Although N mineralization is greater in undisturbed than in disturbed soil samples [

51], the mineral N content in disturbed soil—possibly due to an increased OM mineralization rate—is equal or even exceeds the amounts of mineral N released into the soil by the feedstocks and their derived biochars, despite no additional N being supplied to nourish maize plants. In a study involving the application of biochar-based fertilizers derived from the composting process, effects similar to those found in this study were observed, where, due to soil disturbance, there was an increase in and high levels of mineral nitrogen in the soil solution [

52].

Regardless of the evaluated N source, mineral N content is higher in the clayey Oxisol than in medium-textured Oxisol. Soil N availability depends on the organic matter content and the turnover of organic N into mineral N through mineralization [

53]. Overall, available N levels in the whole Oxisol samples vary; but, in most treatments, they fall within the range considered optimal for full maize growth. The amount of N required in the soil for adequate plant growth varies among crops and is also influenced by root depth. Overall, in field trials, N levels in whole soil samples should not fall below 10 mg kg

−1; and should not exceed 50 mg kg

−1. For a set of Brazilian soils, maize N uptake was strongly correlated with potentially mineralized soil N, with 130 mg kg

−1 N identified as sufficient for optimal N uptake in plants grown under greenhouse conditions [

54].

In whole soil samples, the NH

4+:NO

3− ratio varied according to soil type and the N source added to the evaluated Oxisols. Nitrate and ammonium are the primary forms of nitrogen taken up by plants; although, some plants can also absorb amino acids. Maize growth and yield are favored by an ammonium-N:nitrate-N ratio close to 50%:50%. A NO

3−:NH

4+ ratio of 1:1 at two weeks after planting resulted in higher maize grain yields (6097 kg ha

−1) compared to a 1:0 (5415 kg ha

−1) or a 0:1 (5328 kg ha

−1) ratio. A NO

3−-N:NH

4+-N ratio of 1:0 does not adequately meet plant N requirements, whereas a 0:1 ratio led to ammonium toxicity effects [

55]. The ammonium:nitrate ratio affects gene expression, plant growth, and development, as the exclusive presence of ammonium induces anthocyanin accumulation, while reducing biomass, chlorophyll, and flavonoid accumulation [

56]. Ammonium and nitrate have distinct effects on plant physiology. Compared to nitrate, ammonium reduces root growth and leaf surface area, limiting CO

2 fixation and thereby restricting plant growth. However, due to energy savings and easier metabolism in ammonium-treated plants, the CO

2 assimilation rate is higher than in crops exclusively nourished with nitrate-N [

57].

Regardless of the N source supplied to plants, at the end of maize cultivation, the remaining levels of mineral N in the soil (residual N) are relatively low and insufficient to meet the N requirements of most crops. Such reduced levels of available N are common for mineral fertilizers such as ammonium nitrate, and the results of this study indicate that additional N fertilizer is required for plants grown in succession to maize. Conversely, according to Carvalho et al. [

58], biochar-based N fertilizer (BBF), formulated with urea and derived from coal processing fines for steel production, exhibited a greater residual effect compared to the exclusive use of urea for oat nutrition. This effect was attributed to the slow N release from BBF. In agreement with Carvalho et al. [

58], the combined use of mineral N and biochar improves N use efficiency in crops and enhances residual N levels in soils after corn harvest. This approach is promising for the development of novel fertilizers with improved agronomic efficiency to supply N to crops.

Biochar supplies more N in available forms for crops than its precursor feedstock [

15,

59], which aligns with the results reported in this study. Soil type is a key factor influencing N availability in response to the different N sources tested. The use of biochars derived from chicken manure and shrimp carcass increased the availability of nitrate-N in the soil to levels even higher than those observed in treatments where N was supplied as ammonium nitrate. The two Oxisols examined in this study have different capacities to supply N for maize. The LVd (clayey Oxisol) was able to provide greater amounts of N than most feedstocks and their derived biochars when added to the medium-textured Oxisol (LVa). According to Morais et al. [

60], N availability in soils was initially higher in BBF-treated soils compared to soils treated with mineral N fertilizers. However, the effects of BBFs on N availability, both in whole soil and in soil solution, did not significantly influence N uptake by maize shoots or overall plant N accumulation. These findings suggest that the similarity in plant N uptake between BBFs and NPK mineral fertilizers cannot be solely explained by the amount of N added through fertilization. N in biochar exists in various organic forms, with its mineralization rate controlled by decomposer activity and abiotic factors, such as soil type [

61]. Since a significant portion of N in BBFs is in organic forms, biochar N-doped matrices are more prone to gradual mineralization over time, leading to increased residual soil N levels in the long term, for crops cultivated in succession after maize [

60]. However, regardless of the N source, after maize is cultivated in pots, the residual N in the whole Oxisol reduced and was insufficient for plants in succession, even in soils treated with readily available N from urea [

30]. Therefore, further sequential field experiments should be conducted under real field conditions to assess the potential of biochar-based N fertilizers to supply and sustain crop nutrition over the medium and long term in soil types with different organic matter contents.

The soil–biochar interaction exerts a strong influence on the prevalence of the nitric-N form in solution over N in the NH

4+ form. In the clay Oxisol, nitrate-N prevails over N-ammonium, mainly in the samples treated with biochar + ammonium nitrate. In addition, the ammoniacal-N form predominates in the clayey Oxisol at levels exceeding 1000 mg kg

−1, which far exceeds the threshold content range recommended for plentiful maize growth in nutritive solutions. Availability of N-nitrate or N-ammonium in the solution is regulated by the soil type–N source interaction [

10,

62]. Nitrogen is available in the soil solution at greater levels than those determined in whole soil. In fact, N was found in the soil solution at levels that exceeded the optimal range of mineral N (80–160 mg L

−1) for the full growth of plants in nutrient solutions, e.g., hydroponic solutions [

63]. This prevalence of N-ammonium over N-nitrate in treatments where biochar was combined with ammonium nitrate is thought to hinder maize growth due to excess available N, and an imbalance in the ammonium ratio decreases maize growth, which is favored when the NH

4+:NO

3− ratio is found in soils in a balanced proportion, ideally at a ratio greater than 1:1 [

64].

When added to the two Oxisols, biochars favor the nitrification process; although, this effect is restricted to the weathered soil with the highest clay and OM contents (clayey Oxisol). In fact, the nitrification process is enhanced by the presence of biochar in the soil, but it takes time for the biochar matrix to play a role in the conversion of ammonium into nitrate [

8,

9,

10]. In the medium-textured Oxisol (LVa), there is only a greater availability of nitrate-N in soil samples after 15 days of maize cultivation. The role played by N sources in soil available N depends on their interaction with soil constituents; thus, the prevalent form of N in the soil requires further study. In addition, it is necessary to verify the main features and biochar properties that influence the nitrification rate, which is specific for each soil type. The levels of mineral N in the solution of both Oxisols exceeded the levels of mineral N in the whole soil. It is necessary to investigate if the high levels of ammonium and, mainly, nitrate, are detrimental to maize nutrition and growth.

Equally important is the need to evaluate the positive priming effect of soil structure disruption on increasing the decomposition rate of native soil organic matter and soil nutrient availability. In soil, the use of biochar—depending on its application rate and composition—can either enhance or hinder the supply of N to crops due to increased N immobilization by soil biota and within the biochar structure itself [

10,

65]. Beyond its high N content, an imbalance in the forms of N supplied to maize exists within the soil solution. To date, this is the first study to evaluate ammonium and nitrate levels, as well as their ratios, in whole soil and soil solution for maize biomass production in response to biochar, organic residues, and ammonium nitrate as N sources. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first time that mineral N contents have been analyzed in the soil solution of highly weathered Brazilian soils. Our findings indicate that native soil organic matter plays a key role in the exceptionally high mineral N content observed in the Oxisol solutions. At least in pot experiments, organic matter can effectively contribute to increasing readily available N in the solution for maize grown in disrupted cultivated Oxisols. Surprisingly, the mineral N levels in the soil solution exceed the critical thresholds recommended for plant growth in nutrient solutions and hydroponic media. For instance, some crops, such as lettuce and leafy greens, typically require 150–200 mg L

−1, while fruiting crops like tomatoes and peppers may require 200–300 mg L

−1 at peak growth stages [

63,

66].

The effects of N dynamics modified by the addition of biochars and their conjugated use with ammonium nitrate demonstrate a direct impact on variables such as dry mass, N accumulation, and the SPAD index, which is used indirectly to assess the N nutritional status [

67,

68]. In this study, the SPAD index did not reflect the availability of N in the soil and does not anticipate the N accumulated by maize, nor can it predict the effects that the soil types and treatments studied have on the production of maize biomass. This indicates that maize leaf greenness reflects higher levels of N uptake by maize when fertilized with organic residues, biochars, and biochar + ammonium nitrate, mirroring the photosynthesis rate and chlorophyll content in maize leaves. Thus, it is possible to infer the N nutritional status of maize plants through a quick reading with a chlorophyll meter (SPAD index). Furthermore, it is evident that, in general, the maize growth indices (SDM, NAc, SPAD) are positively correlated with the levels of mineral N (N-NH

4+ and N-NO

3−), both in whole soil and soil solution; although, the variability of maize biomass is better explained by the availability of N in the soil solution. Therefore, the uptake and accumulation of N by maize plants are partially controlled by the availability of N in the Oxisol solution rather than by the N in the whole Oxisol.

Overall, the accumulation of N in maize plants is greater in the medium-textured Oxisol (LVa), without implying a greater production of maize dry matter. N uptake without a corresponding increase in plant growth is classified as N luxury consumption. Maize shoot N accumulation is enhanced by the combined use of ammonium nitrate and biochar, particularly when ammonium nitrate is combined with chicken manure and shrimp carcass biochars. The use of bamboo and sunflower cake biochars + AN ensured the highest dry matter production in the sandy Oxisol (LVa), while in the clayey Oxisol (LVd), maize dry matter increased mainly due to the application of sunflower cake-derived biochar.

Nitrogen is essential for plants and is a highly reactive element that interacts with and influences the cycles, forms, and dynamics of carbon (C), sulfur (S), oxygen (O), and other elements in the soil–plant system [

69,

70]. The availability of N in soil is regulated by inputs from fertilizers, organic residues, soil organic matter (SOM), biochar, and the activity and diversity of soil biota [

10]. The supply of N to crops depends on several factors, including the biochar C/N ratio, N content, recalcitrance of N forms, and water-soluble carbon content. These factors ultimately determine net N immobilization or mineralization and, consequently, the soil’s capacity to supply N to crops [

8,

10,

71,

72,

73]. Soil dissolved organic carbon (DOC) undergoes rapid turnover, while relatively stable pyrogenic carbon (PyC) and aromatic hydrocarbons present in biochar decompose much more slowly [

38]. In biochar-treated soils, bioavailable N (NH

4+ and NO

3−) initially decreases but gradually increases over time. Soil microbes preferentially decompose fresh plant litter over recalcitrant N pools found in SOM [

9,

50], thereby slowing the overall SOM turnover rate [

38]. In other words, compared to fresh organic matter, older SOM and N in biochar with high aromatic characteristics form more stable and persistent N sources for plant uptake, reducing N losses, especially in the presence of biochar; although, this also limits their immediate availability as N sources for crops [

9]. Although the aging process of biochar may indirectly affect the nitrogen cycle, detailed investigations into the coupling of soil/biochar carbon and nitrogen cycles remain limited. The interactive mechanisms involved are not yet fully understood, and the regulatory role of biochar in this process—whether in the presence or absence of plants—has yet to be fully elucidated.

Biochar effectively retains soil nutrients and enhances nutrient uptake by crops by stimulating microbial and enzymatic activity. It possesses a well-developed pore structure and high biochemical stability, along with strong sorption and redox capacities due to multiple organic functional groups and its large specific surface area and pores, which allows it to compete for mineral surface sites [

74,

75]. Additionally, biochar plays a regulatory role in activating or inactivating soil biota and soil processes involved in the release of nutrients, hormones, and toxins by influencing alkaline functional groups [

76,

77]. Its indirect effects on soil amendment and nutrient cycling are often more significant than its direct effects; this is similar to soil organic matter (SOM), which acts as a microdomain framework, maintaining balance among the solid, liquid, and gaseous phases in soil [

38,

71].

This study, due to the high number of treatments tested, demonstrated the potential of biochar as a nitrogen source and its interaction with nitrogen sources. Despite the high potential of this study, further research under field conditions is necessary to validate the technology, confirming in commercial cultivation conditions the increase in nitrogen use efficiency resulting from the use of biochar. The complex interaction of plant traits regulating crop yield in the dynamic environments experienced by field-grown plants [

78] should be considered when designing controlled experiments to effectively improve wheat growth and grain yield [

79]. According to Sales et al. [

79], when breeding plants for specific environments, a better alignment between phenotypes in field and greenhouse conditions can be achieved by designing experiments in which key conditions match the cropping cycle of the target breeding environment. While controlled environment studies (e.g., greenhouse conditions) are valuable for large-scale assessments of soil types, nutrient closed systems, and testing of a full range of nutrient and fertilizer sources on nitrogen availability and plant growth, it is essential to validate these findings under field conditions. Genotypic traits that contribute to crop growth and grain yield may behave differently in the field due to environmental factors, plant–genotype interactions, and stress conditions. These factors can significantly influence plant growth and yield in ways that differ from greenhouse experiments.