Since the environmental disaster in Minamata Bay, Japan, in the 1950s, the scientific community has made significant progress in understanding the effects of methylmercury exposure on the brain. But how methylmercury affects other bodily systems has received less attention.

Matthew Rand, Ph.D., a member of the NIEHS-funded Environmental Health Sciences Center (EHSC) at the University of Rochester, recently published research into the effects of methylmercury exposure on muscles.

The fruit fly — a model organism

“Applying Drosophila to a toxicology problem is a natural pairing — the fruit fly provides an exquisitely powerful molecular model to study the developmental effects of mercury exposure,” Rand told Environmental Factor. “Much of the research community’s understanding of neural and muscle development in general has come out of genetic research in flies.”

He said that his team used Drosophila as a model organism not only because it reproduces rapidly but also because fundamental pathways that control synapses between motor neurons and muscle fiber in the flies are present in humans and other animals.

Biological mechanisms of toxicity

Rand’s group focused on methylmercury’s targeting of the Neuroligin 1 gene (NLG1). That gene plays a role in the formation and homeostasis, or maintenance, of the synapses between neuron-neuron and neuron-muscle interactions.

The researchers investigated how methylmercury exposure affects flies’ indirect flight muscles because the architecture is similar to that of mammalian and vertebrate muscle.

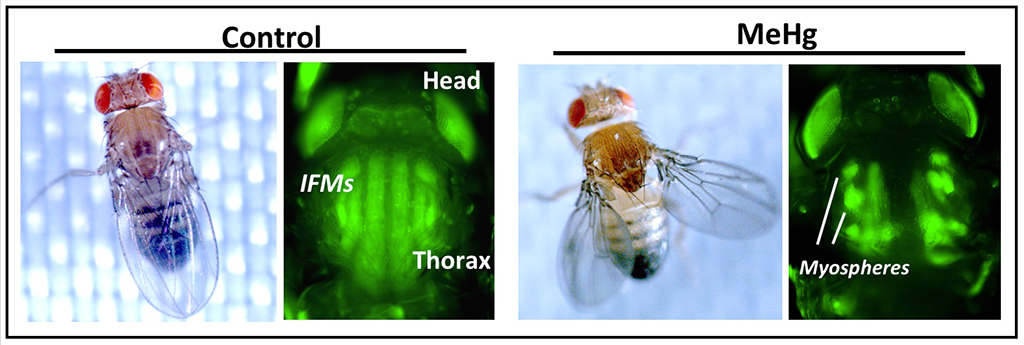

Adult flies at rest holds their wings crossed-over and flat, extended posteriorly (see left, “Control”). Wing position is maintained by the regular array of indirect flight muscles (IFMs) appropriately attached to the thoracic cuticle. Adult flies that were exposed to methylmercury (MeHG) during larval and pupal development exhibit wings that are outstretched when at rest, consistent with an inability to position the wings due to myospheres that form because of unstable muscle attachments (see right, “MeHg”). (Image courtesy of Matt Rand)

“We can correlate form and function with actual motor behaviors of flight to really nail down the function of NLG1,” Rand said. “This research has led us to the indirect flight muscle and the neuromuscular junction as methylmercury targets, which has unveiled candidate genes in synapse formation and maintenance that may explain a bit of what the mercury toxicity mechanism is about.”

Human relevance

Lawrence is an expert in how environmental pollutants can affect immune function and the body’s ability to fight infection. (Photo courtesy of Paige Lawrence)

Lawrence is an expert in how environmental pollutants can affect immune function and the body’s ability to fight infection. (Photo courtesy of Paige Lawrence)EHSC Director B. Paige Lawrence, Ph.D., noted the importance of translating mechanistic scientific research into information that is applicable to how methylmercury affects humans.

“Our center facilitates exactly the type of innovative research that Dr. Rand has conducted to help resolve the persistent issue of environmental mercury toxicity,” she said.

“This type of translational environmental health science is what makes significant advances happen, and it is made possible through our unique collaborative environment as well as the cores and facilities supported by NIEHS,” Lawrence added.

Genetic resistance

Rand noted that uncovering the biological mechanisms behind mercury toxicity also has informed research on whether methylmercury exposure can be counteracted by natural genetic resistance. Mercury toxicity is almost certainly polygenic, which means that it affects multiple genes, he noted, referencing the Seychelles Child Development Study (see sidebar). The goal of that initiative is to understand how prenatal exposure to the substance affects neurodevelopment.

“The Seychelles study as a whole has had somewhat unexpected results,” Rand said. “There isn’t a main effect of mercury on child neurodevelopment across several cohorts. What we are uncovering are the mechanisms of toxicity — and what are the conditions that enable resistance.”

He added that if scientists come to understand the dynamics of toxicity resistance, those conditions can be optimized through interventions and dietary supplementation that could reduce some of the risks of methylmercury exposure.

“A lot of toxicology research aims to find out where things are the most sensitive and emphasize where harm could happen,” Rand said. “But I like to embrace the philosophy that there are mechanisms we have that allow us to be protected. We can optimize those to alleviate risk and fear.”

Citations:

Harada M. 1995. Minamata disease: methylmercury poisoning in Japan caused by environmental pollution. Crit Rev Toxicol 25(1):1–24.

Peppriell AE, Gunderson JT, Krout IN, Vorojeikina D, Rand MD. 2021. Latent effects of early-life methylmercury exposure on motor function in Drosophila. Neurotoxicol Teratol 88:107037.

Gunderson JT, Peppriell AE, Krout IN, Vorojeikina D, Rand MD. 2021. Neuroligin-1 is a mediator of methylmercury neuromuscular toxicity. Toxicol Sci 184(2):236–251.

(Kelley Christensen is a contract writer and editor for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

Source link

factor.niehs.nih.gov