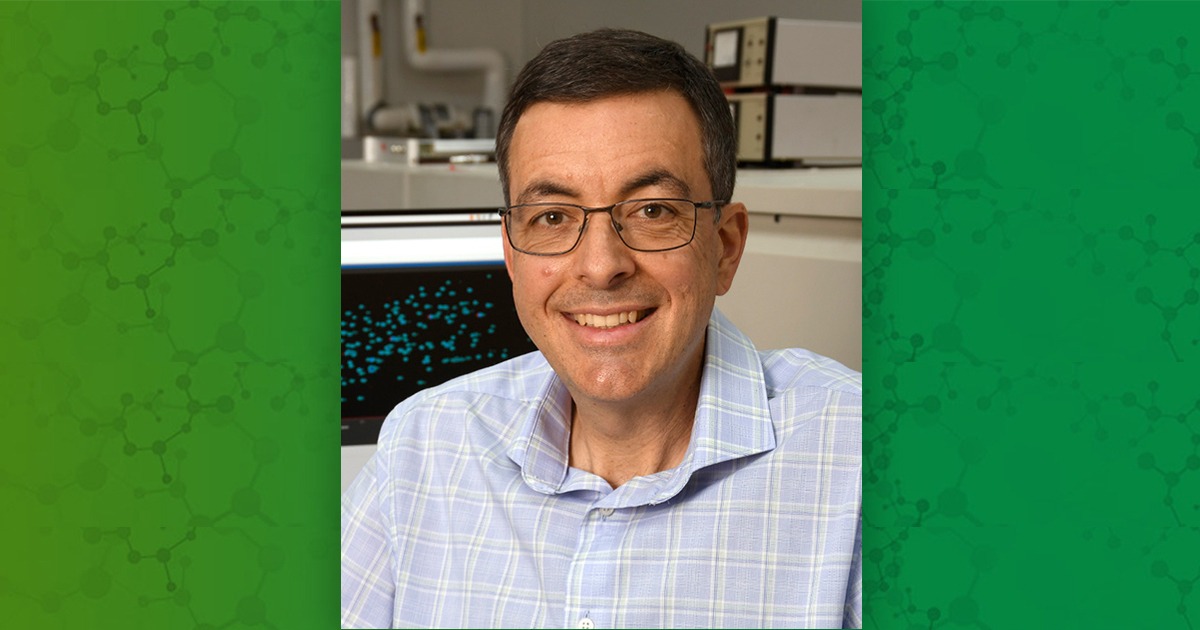

Geoffrey Mueller, Ph.D., director of the NIEHS Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Research Core Facility, was awarded the John W. Yunginger, M.D., Memorial Lectureship at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) held in Phoenix, Arizona, in February. The award honors significant scientific contributions of AAAAI members.

Mueller was recognized for his work exploring the structure and function of allergens and his quest to develop effective therapeutic antibodies to help people who have severe allergies. The Environmental Factor visited Mueller at his NIEHS laboratory to learn more about his research and the scientific advancements he strives to reach.

Where it all began

Mueller’s love for science, and more specifically physics, flourished during time spent in the inaugural class of the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria, Virginia, which today is ranked the #1 high school in the U.S.

His impressive research portfolio began when he earned a doctorate in biophysics at the University of Virginia. His dissertation, a black-bound book that still resides on his desk, examined the structure of one dust mite allergen, Der p 2, using a structural biology technique called nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometry.

He continued this work, using NMR techniques, in a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Toronto before joining NIEHS in 2001 as a staff scientist. He has since expanded this research of structures of various dust mite proteins and other allergens, and in 2020, Mueller became director of the facility and head of the NMR Group.

Not all nuts are equal

At the AAAAI conference, Mueller presented on the common properties of allergens. The allergens he works with include dust mites, cockroaches, cats and dogs, and foods such as shellfish, peanuts (legumes), walnuts (which are considered nut-like drupes), and cashews and pistachios (which are drupes). These differences matter a lot when investigating the proteins in each that cause an allergic reaction in humans.

Mueller and his team characterize allergens molecularly through a set of structural biology techniques. There are three ways to investigate the chemical structure of proteins: cryo-electron microscopy, x-ray crystallography, and NMR. The Mueller Lab recently published a study on the cross-reactivity of the peanut and the walnut, and now they are examining data regarding peanut and pistachio or cashew allergies.

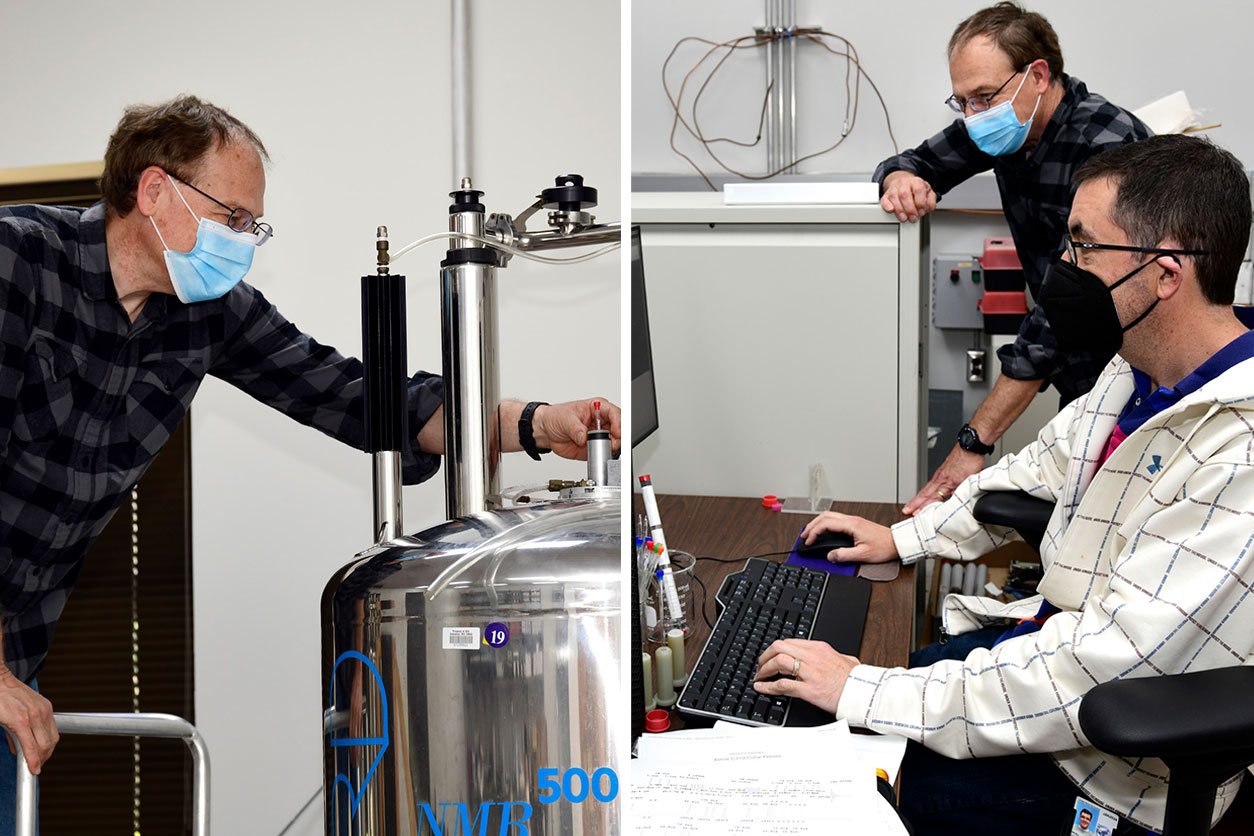

Mueller stands next to the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometer. The power housed within this machine is equivalent to two sticks of dynamite, yet it creates molecular structures at the atomic level without destroying the atom. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Mueller stands next to the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometer. The power housed within this machine is equivalent to two sticks of dynamite, yet it creates molecular structures at the atomic level without destroying the atom. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)“Within this cohort of patients, there seems to be different patterns between people who are mono-sensitized versus people that are dual-sensitized,” Mueller said. Here, mono means allergic only to peanuts, and dual means allergic to peanuts and one of the other nuts (pistachio or cashew).

“It’s odd because peanuts and pistachios or peanuts and cashews are not even cousins,” he noted. “Pistachios and cashews are closely related. Peanut, however, is actually distantly related, so it is a little bizarre that people frequently have dual-sensitization allergies. We have three supposedly different populations here, and they do seem to show different patterns of sensitization, which is interesting.”

So, he asks, “Are there common sensitizing factors?”

Let’s take a closer look

The NMR process is a complicated science that involves measuring atomic frequencies that Mueller and his colleagues can closely examine.

First, they isolate the protein and use the NMR process to create a 2D scatterplot of the frequencies that he calls a “fingerprint.” This frequency fingerprint serves as a key to unlock the protein’s structure.

“Each one of those points is a coordinate for a nitrogen atom and a hydrogen atom, which are bound to each other,” Mueller explained.

Then, a 3D and even a 4D image can be created from that fingerprint key. Spectroscopy, the absorption or emission of light by matter, can help identify how each allergen protein is uniquely shaped, how and where it binds to other materials, and where spaces typically exist throughout the structure.

Scott Gabel, Ph.D., left, a biologist in the Mueller Lab, deposits an allergen protein into the NMR machine. Mueller and Gabel then examine the output on the computer (right). The fingerprint on the screen serves as a map for further experiments. (Photos courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Scott Gabel, Ph.D., left, a biologist in the Mueller Lab, deposits an allergen protein into the NMR machine. Mueller and Gabel then examine the output on the computer (right). The fingerprint on the screen serves as a map for further experiments. (Photos courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)“The fingerprint is a jumping-off point for more experiments,” Mueller said. “So, you start with that, and then in the third dimension, you do another experiment that asks which features are close by in space or which are connected by a bond, and you can manipulate a third-dimension or sometimes a fourth-dimension experiment to investigate which atoms are close by. That’s the really cool thing about NMR, compared to other techniques, because, for example, you can see which one of those peaks shift in response to a chemical, and it gives you binding information.”

Antibodies as therapeutics

Mueller also gave a continuing education course at the AAAAI conference titled “Molecular Characterization of Allergens and Specific IgE Antibodies.”

“The major direction in the future is looking at how antibodies react with allergens,” Mueller said. It has only been in the past five years that the human antibodies that cause allergic symptoms have been cloned and examined in isolation.

“IgE antibodies, which are rare and circulate in low levels, have been notoriously difficult to clone out of people because the memory cells are exceedingly rare,” he noted. “We are finally now getting real human IgE antibodies to allergens. I really see that as the next frontier as far as exploring their structure and getting a deeper understanding from that. We ask, ‘What is the human repertoire to allergens?’”

Mueller said his work leads to two possible new treatments for allergies.

“One is to redesign allergy shots to be a safer form of immunotherapy,” he explained. “Second are therapeutic antibodies. With allergy shots, I am giving you the allergen and telling your body, ‘Figure out what to do with this in a different way.’ What if I just gave you the antibodies you need? We are collaborating on ways to create these new technologies to benefit people within the next 10 years. Moving from immunotherapy to delivering therapeutic antibodies is probably the first major new idea in 100 years for treating people with allergies.”

Mission-driven

An allergy is an accidental over response to foreign matter. It is an inappropriate response to something normally considered harmless. Mueller hypothesizes that therapeutic antibodies could intercept the allergen before it causes symptoms.

The science emerging from the NIEHS Mueller Laboratory has the potential to help millions of people, which is not lost on him. He has good reason to want to help people who have severe allergies.

“She’s allergic to everything,” he said about his 21-year-old daughter, Madison. “It is almost ironic because I got interested in allergens in graduate school, before she was born.”

He too suffers from allergies. “I researched the dust mite allergen because I was allergic to dust mites.”

But his drive is not only personal, it is mission centric.

“I really like my job, and I am really motivated to develop new therapies,” Mueller said about his career as a federal scientist. “We try to focus on making sure we are doing research on the health outcomes for people, which is the mission of our institute.”

Citation: Foo ACY, Nesbit JB, Gipson SAY, Cheng H, Bushel P, DeRose EF, Schein CH, Teuber SS, Hurlburt BK, Maleki SJ, Mueller GA. 2022. Structure, immunogenicity, and IgE cross-reactivity among walnut and peanut vicilin-buried peptides. J Agric Food Chem 70(7):2389–2400.

(Jennifer Harker, Ph.D., is a technical writer-editor in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

Source link

factor.niehs.nih.gov