Global leaders in science, medicine, and business, including from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), recently launched an unprecedented initiative to share knowledge and resources for quantifying how our environments influence health. The global initiative builds on momentum to comprehensively and systematically measure the exposome, which is the integrated compilation of all physical, chemical, biological, and psychosocial influences that impact biology throughout one’s life course.

“Today, we took one small step for exposome science, one giant leap for prevention,” said Thomas Hartung, M.D., Ph.D., who co-hosted the Exposome Moonshot Forum at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center.

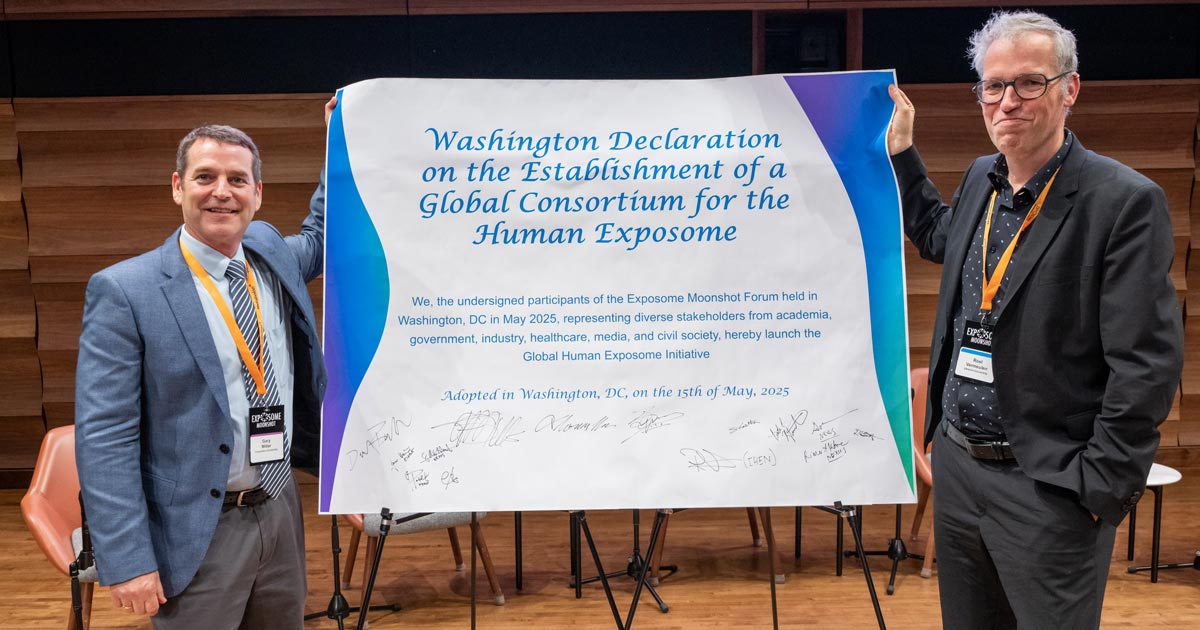

More than 400 individuals from 30 countries in North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa gathered in Washington, D.C., and virtually to take part in the forum May 12-15. Participants committed to collaborating across scientific disciplines, public and private sectors, and national boundaries to foster advances in understanding environmental health risks, and to provide improved tools for disease prevention, diagnostics, and treatment.

“If we really want to influence human health, we have to develop a bold vision and think creatively about how we can work together to study the complex interplay of different environmental exposures,” said NIEHS Director Rick Woychik, Ph.D., during his keynote address.

Forum participants accepted the challenge, sketching out plans during panel and breakout sessions over the course of three days. Their goal: Create a research framework to collaboratively bridge emerging technologies, big data, and AI with ethical and social considerations to advance exposomics, which is the study of the exposome.

Global commitment

Now is the time to launch a global human exposome initiative as the necessary complement to the Human Genome Project, say organizers of the recent forum. The reason: Studies show the environment may be a major contributor to chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and heart disease.

Nearly 25 years ago, the completion of the first draft of the Human Genome Project launched a new era that helped scientists move beyond studying a single gene’s effects to understanding how all genes together shape health. Developing the technology to sequence the entire genome included a $3.8 billion investment from the U.S. government. The return on that investment: nearly $1 trillion dollars in economic activity from 1988-2010, according to a 2013 report.

“A similar investment in our future and the exposome means we’re not investing in hospital wings later,” said Hartung. “Prevention is cheaper than prescription.”

To that end, experts now say it’s time to move beyond measuring one environmental exposure at a time to determining the health effects of the many exposures people encounter every day.

“During the last 10 years, a lot of work has been occurring across many different labs and research groups, but we need to come together now in a focused effort to really drive exposomics forward,” said Gary Miller, Ph.D., who co-leads the Network for Exposomics in the U.S. (NEXUS). A half-dozen NIH Institutes and Offices, led by NIEHS, support the NEXUS research coordinating center.

The Network for Exposomics in Europe (IHEN), alongside the European Infrastructure project EIRENE, are viewed as key collaborators in this effort. EIRENE, led by Jana KIánová, Ph.D., seeks to develop a network of harmonized laboratories, environmental studies, population cohorts, and databases for human exposome research. An NIEHS delegation, including Woychik, Division of Extramural Research and Training Director David Balshaw, Ph.D., and Sri Nadadur, Ph.D., chief of the Exposure, Response, and Technology Branch, visited KIánová’s team at Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic, last fall.

Precision health, precision prevention

Thanks to a convergence of technical advances, scientists can now determine how the environment and genes interact to affect a person’s unique biology and health.

Newer technologies, including mass spectrometry and nanotechnology, allow scientists to measure hundreds of chemicals in a simple blood, tissue, or tumor sample.

“We now have so much more information from human samples, and satellite imaging, and sensors to measure our external environment,” explained Miller. “Using improved systems for data analysis, artificial intelligence, and machine learning allows us to bring all of these datasets together to study the exposome at a level we couldn’t just a few years ago.”

The ability to link exposures — whether external like air pollution or internal like stress — to changes in a person’s biology can be used to understand risk factors and improve health at the individual and population level.

“The compilation of different factors — be it the air we breathe, water we drink, chemicals we are exposed to, experiences we have, nutrition we eat — are all very important for health outcomes,” said Roel Vermeulen, Ph.D., of Utrecht University, Netherlands, who co-leads the Network for Exposomics in Europe (IHEN). “If we want to combat the large burden of chronic diseases, we need to better understand what those drivers are. Without knowing what the sources of those drivers are, we will not be able to devise effective prevention programs.”

And those prevention efforts hinge on everyday citizens taking part in research to collaboratively uncover how environmental factors are influencing their health.

“Exposome research is about citizen science and bringing together biomedical science and environmental science with citizen science,” said Denis Sarigiannis, Ph.D., who directs the National Hellenic Research Foundation in Greece. “In the end, we want to enhance our positive impact on public health. Exposome data can guide the policies that shape health outcomes.”

Prevention may be paramount, but exposome data also can be used to halt disease progression and improve treatment.

“When people do get sick, exposome data could reveal how the environment may interfere with a treatment,” Miller said. “Exposomics can inform why a particular drug doesn’t work as well as it should or why certain people don’t respond to chemotherapy or statins.”

The challenge ahead

Although the Human Genome Project centered on one scientific task, the exposome equivalent seeks to accomplish many. By reaching across multiple scientific disciplines, the forum drew experts in chemistry, biology, epidemiology, toxicology, public health, clinical research, patient care, data science, AI, policy, ethics, law, and social science.

During the breakout sessions, forum participants, including scientists, physicians, venture capitalists, policymakers, and patient advocates, shared what they hoped the initiative could achieve in the coming years. Some highlights include the following goals.

- Establish a coordinated governance structure that facilitates sharing of knowledge and enhances collaborations to support long-term research and innovation.

- Develop a common language and shared vocabulary so that researchers from different scientific disciplines can better communicate with each other.

- Standardize measurement protocols and analysis workflows to harmonize exposome data.

- Advance technologies — such as wearable exposure monitors, satellite imagery, and screening methods — and develop new analytical platforms to integrate and analyze the vast amount of data such technologies create.

- Build a large-scale global infrastructure to facilitate open access to necessary technologies, data, and tools to research teams in all regions.

- Establish best practices to guide the ethical, legal, and psychosocial aspects of collecting, analyzing, and sharing exposomics data to ensure responsible research practices, accountability, and distribution of benefits.

- Harness the power of AI to better predict disease risk and translate exposomics for use in clinical settings.

Keeping focused on the guiding principles driving the exposome initiative can help clarify markers of success, according to Sara Adar, Sc.D., University of Michigan School of Public Health.

“We’re trying to make a better and healthier world by providing evidence-based research that will ultimately change policies and interventions to improve people’s health, either to reduce risk or increase benefit,” Adar said. “And we’re trying to train and do capacity building so there is a whole new generation of people to do this important work.”

Adar and her colleagues Jinkook Lee, Ph.D., and David Knapp, Ph.D., of the University of Southern California, lead the Gateway Exposome Coordinating Center, a National Institute on Aging-funded center working to help curate and harmonize environmental data ranging from air pollution and workplace exposures to social isolation, community services, access to health care, life events, and public policies. (See sidebar for additional resources supporting exposomics research.)

Next steps

“The NIH Real World Data Platform is one way that we can turn the ideas and the needs raised at this forum into real actionable science,” said Acting NIH Deputy Director for Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives Nicole Kleinstreuer, Ph.D.

She added that integrating the exposome into the NIH Real World Data Platform is not just a technical challenge, it is a scientific imperative.

“It means expanding how we think about exposome assessment, harmonizing diverse data streams from environmental monitoring to wearable sensors, biospecimens, geospatial tools, social data, and doing so in a way that is scalable, secure, and standardized,” Kleinstreuer said.

Keeping the momentum and conversations generated by the forum going is another priority for forum participants.

“I’m planning to be intentional about reaching out to others outside my discipline, asking for their inputs, and being receptive to other paradigms that may be a better fit for a given study or question,” said Kirsten Overdahl, Ph.D., a mass spectrometrist and acting coordinator of the NIH Metabolomics Consortium. She noted the breakout sessions allowed her to meet air pollution experts, environmental litigators, and startup CEOs, who shared opportunities and barriers for exposomics technology.

“Bringing all of the different researchers from different disciplines together is a big undertaking, and I’m looking forward to the working groups and continued discussions that will come out of the forum,” said Douglas Walker, Ph.D., an environmental engineer, analytical chemist, and NIEHS grant recipient at Emory University.

(Caroline Stetler is Editor-in-Chief of the Environmental Factor, produced monthly by the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

Source link

factor.niehs.nih.gov