Thomas LaVeist, Ph.D., from Tulane University, delivered the second NIEHS Olden Distinguished Lecture on Feb. 22. His virtual presentation was titled “Segregated Spaces Are Risky Places: The Social Environment and Inequalities in Health.”

LaVeist is the Dean and Weatherhead Presidential Chair in Health Equity in Tulane’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. He is a member of the National Academy of Medicine — among numerous other accomplishments — and a renowned expert on the social and behavioral factors that influence health outcomes.

The lecture series was created in honor of Kenneth Olden, Ph.D., former director of NIEHS and the National Toxicology Program (NTP). It recognizes outstanding achievement in the field of environmental health sciences and environmental justice, and it promotes diversity in the scientific community. LaVeist’s talk was hosted by Olden; Rick Woychik, Ph.D., NIEHS and NTP director; and Trevor Archer, Ph.D., the institute’s deputy director.

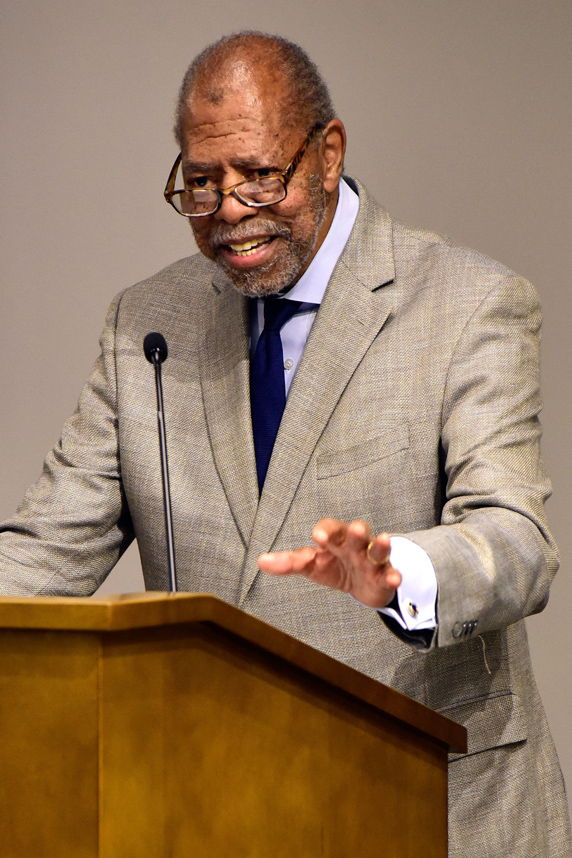

“I’m very impressed that Tom addressed the issue of place,” said Olden, shown here delivering the inaugural lecture in the series. “Place matters, the environment matters.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

“I’m very impressed that Tom addressed the issue of place,” said Olden, shown here delivering the inaugural lecture in the series. “Place matters, the environment matters.” (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)LaVeist sought to refocus the debate on health disparities away from race per se and toward the social and environmental determinants of health.

“African Americans live sicker and die younger than all other racial and ethnic groups,” he told attendees. “The question is why?”

Common health disparities myths

According to LaVeist, there are three popular myths about health disparities.

Myth 1: Equal access to health care will solve the health disparities problem.

He cited a study about referral rates for an important medical procedure. All patients were insured and came in seeking care, and the health care facilities all had ability to perform to the procedure. Yet 82% of white patients who would have benefited from a referral received one while less than 60% of Black patients did.

Myth 2: Disparities result from biological or genetic differences between groups.

Blaming biology or genetics is the most pernicious myth, noted LaVeist.

“The way this idea creeps into our thinking is subtle,” he said. “It allows people to think that if disparities are biological or genetic in nature, why bother to address them?”

He cited the development of the heart drug BiDil, which is effective in a slightly higher percentage of Black patients than white patients. In 2005, its developers sought approval of the drug — for the first time — for use by only Black patients, leaving the impression that racial differences were key to its effectiveness.

Myth 3: Disparities are caused only by differences in socioeconomic status or poverty.

“Most prevalent among the myths is that poverty or socioeconomic status [is the key aspect of] health disparities,” LaVeist said. “Socioeconomic status is a powerful predictor of population health, but so is race. One does not cause the other.”

The real roots of health disparities

If genetics, healthcare access, and socioeconomic status are not at the root of health disparities, what is? LaVeist emphasized that social and physical environments matter most.

“Although we live in the country together, we experience the country very differently — and that experience makes the difference in health,” he said. “The social and physical environments between Black and white Americans are different. That is where the primary action occurs in producing disparities.”

Using city maps, including one of New York City, he illustrated how racial groups experience different environmental conditions.

“The segregation is clear, as is the lack of resources necessary for a healthy lifestyle,” he noted. “The neighborhood where I grew up, Brownsville, is 1.2 square miles, with a population density about double that for the rest of New York. It also has the lowest life expectancy in the city.”

Environmental justice

There are other environmental issues, LaVeist said, such as proximity to industrial pollution.

“This is the environmental justice question of which I know you all are aware,” he told attendees.

LaVeist drew attention to a stretch of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, where numerous petrochemical plants are located. The area — often referred to as Cancer Alley — is home to mostly Black communities.

“When we look at national statistics, we often come to conclusions about health disparities without accounting for the fact that people live in very different risk environments,” LaVeist said. “We conclude there must be something endemic to people that’s driving the disparities rather than the possibility that it’s the environment they live in.”

(John Yewell is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

Source link

factor.niehs.nih.gov