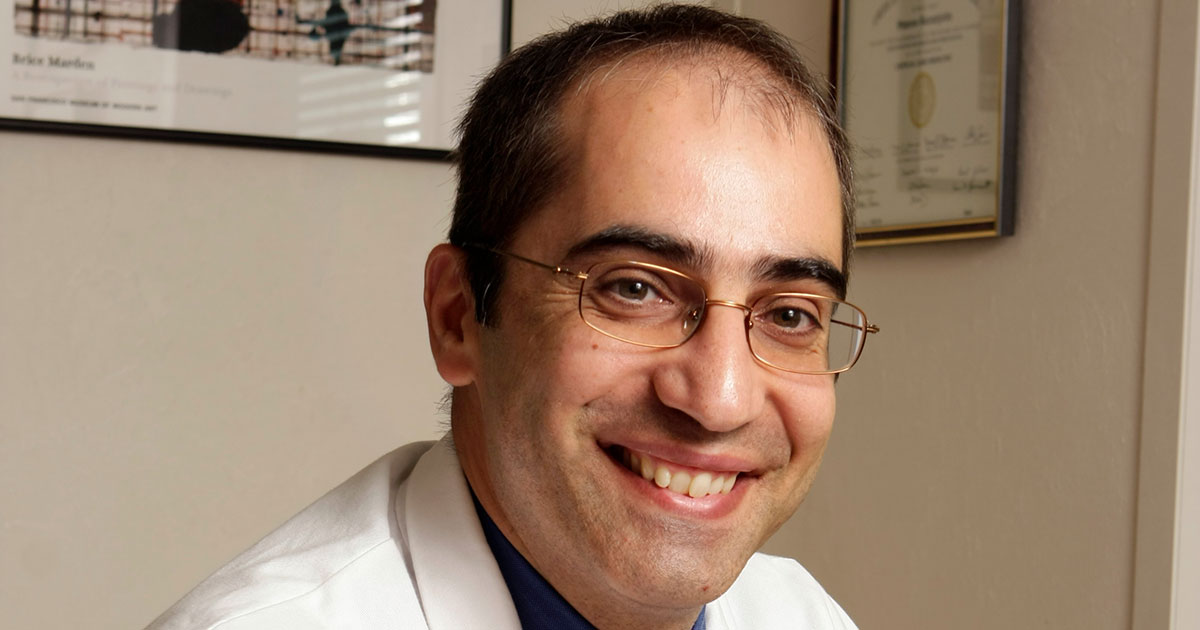

Though World Asthma Day is observed once a year on May 2, asthma is top-of-mind every day for Stavros Garantziotis, M.D., who serves as medical director of the NIEHS Clinical Research Unit.

Garantziotis, a pulmonary and critical care medicine specialist, is principal investigator of the ongoing Natural History of Asthma with Longitudinal Environmental Sampling, or NHALES, research study. The NHALES asthma study follows research participants for five years to assess what role the environment might play in each participant’s asthma symptoms and lung microbiome, or the microorganisms that live in or on the lungs.

The Environmental Factor sat down with Garantziotis to discuss the ongoing NHALES study, what he has learned about the lung microbiome, and how he plans to apply personalized medicine approaches to improve the treatment of asthma.

Environmental Factor (EF): Can you share with us what is at the heart of your current research?

Stavros Garantziotis (SG): The more research I conduct and the more patients I treat, the more I understand that the environment plays an outsized role in both the way diseases develop and the way diseases progress or regress. General health is very much influenced by the environment. Of course, our genes also play a role, but it is always an interaction.

I try to understand what are the mechanisms that trigger lung disease so I can either develop therapies or prevent it from happening in the first place. The goal has always been to understand how the environment interacts with the immune system, because the immune system is particularly important in how our body reacts to environmental triggers that may impact, in this case, the lungs. More recently, it has become a quest to actually personalize that approach and understand for each individual patient what is it about them, their environment, and their past history that influences their disease.

EF: How can recent scientific advances be translated into health gains?

SG: For example, my lab found hyaluronan, a sugar produced in the body and even in the lungs, can prevent and treat viral infections. We published a study about this particular sugar as a treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and we are in the process of publishing a study about its beneficial effects in viral pneumonia.

We are now trying to take that science back to the patient by partnering with industry experts to create an inhalable powder of this particular sugar to use as a treatment in emphysema, viral pneumonia, or as a preventative as a nasal spray during cold season for people with inflammatory lung disease, including asthma.

EF: What should we know about the microbiome of the lungs?

SG: The microbiome, which is part of the environment, interacts with the immune system and influences the onset and progression of lung disease. Through the NHALES Asthma Study, we are examining two major questions. First, how can the microbiome in our lungs change, and can it be influenced by environmental exposures?

Second, does the body and the immune system play a role in shaping the microbiome? In other words, are we just a passive vessel filled with microbes that we inhale, or do we interact with those microbes and end up making them part of our body? We are finding that the answer is yes, the microbes in our body become partners with our immune system.

In the end, we are trying to understand whether we can predict if your asthma is going to flare when something changes in your microbiome. Conversely, are some lung microbes good and induce healthy immune activity similar to how probiotics act in the gut?

EF: How or when does that partnership go awry?

SG: This only becomes a problem when there are environmental exposures that perturb the equilibrium. For example, if you keep inhaling pollutants or keep smoking, those actions continuously trigger and change the microbiome and the way the microbes and immune system are activated. There is also genetic variability or preexisting diseases, such as diabetes, which may change the way the immune system reacts to the microbes, which may make us more susceptible to diseases.

EF: In what ways are you partnering with other scientists to advance research regarding the microbiome of the lungs?

SG: We are excited to be part of and collaborating with the Personalized Environment and Genes Study (PEGS). We collaborate with investigators across NIEHS, National Institutes of Health, and academia regarding how microbiome changes are influenced by the immune system, and we share both expertise and samples. It is a bi-directional communication where we share insights and techniques.

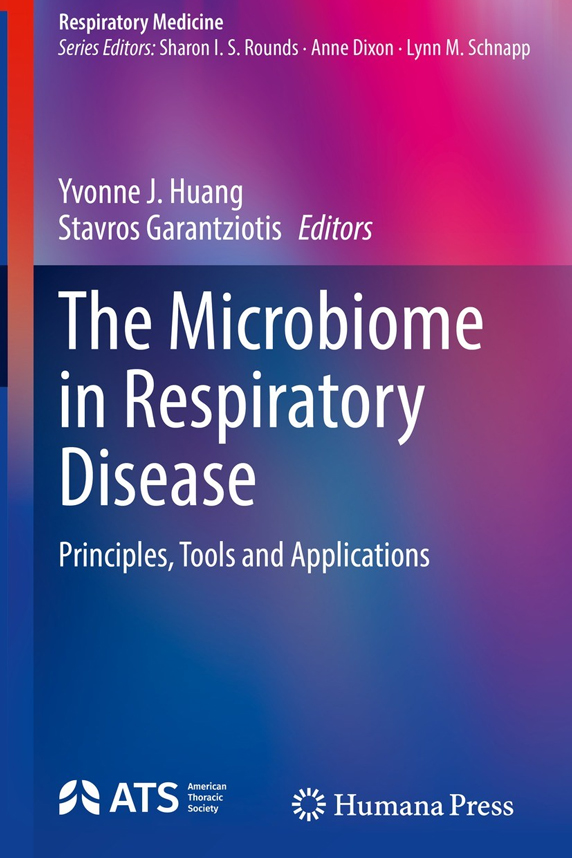

Another ongoing collaborative study with Yvonne Huang, M.D., at the University of Michigan, who has a similar study to NHALES, enables us to compare patient data from the North Carolina environment, which is hot and humid, with the Michigan environment, which is rather dry and much colder.

EF: What one thing could help people better manage their asthma?

SG: A personalized approach to asthma treatment is understanding that not all asthma is the same. I cannot tell you how many patients we have treated who came with severe symptoms and we uncovered something in their environment that after they eradicated that exposure, their symptoms dramatically improved.

What I would ask people to do is to take a close look at their environment and their potential exposures and try to be alert and take control. Managing those exposures goes a long way towards improving asthma symptoms and changing the biology of the lung because it kind of resets the thermostat.

(Jennifer Harker, Ph.D., is a technical writer-editor in the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)

Source link

factor.niehs.nih.gov