Researchers funded in part by NIEHS identified a link between air pollution and dementia using data from long-running projects in the Puget Sound region of Washington.

Scientists from the University of Washington (UW) found that a small increase in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution averaged over a decade at specific addresses in the Seattle area was associated with greater risk of dementia. The research was published Aug. 4 in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives.

“We found that an increase of 1 microgram per cubic meter of exposure corresponded to a 16% greater hazard of all-cause dementia,” said Rachel Shaffer, lead author and former UW doctoral student. “There was a similar association for Alzheimer’s-type dementia.”

Dementia is a disease of the brain that leads to memory loss and changes in mood, and it impairs a person’s ability to think. The most common form is Alzheimer’s disease.

Pollution varies over short distances

Shaffer and colleagues examined data collected from more than 4,000 Seattle-area residents enrolled in the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) Study. Of those individuals, the researchers identified more than 1,000 people who had been diagnosed with dementia at some point since the ACT Study began in 1994.

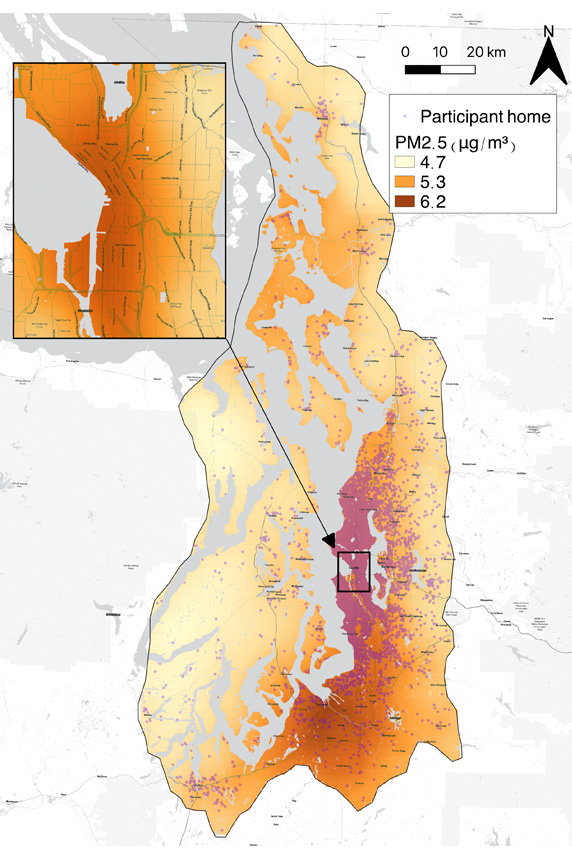

Ten-year average PM2.5 exposure predictions based on 2000–2009 data and smoothed to broadly represent pollution differences in the Puget Sound region. Shaded circles indicate study participant addresses. (Image courtesy of Magali Blanco / University of Washington)

Ten-year average PM2.5 exposure predictions based on 2000–2009 data and smoothed to broadly represent pollution differences in the Puget Sound region. Shaded circles indicate study participant addresses. (Image courtesy of Magali Blanco / University of Washington) Once a patient with dementia was identified, researchers compared the average pollution exposure of each participant leading up to the age at which the dementia patient was diagnosed. For instance, if a person was diagnosed with dementia at 72 years old, the scientists compared the pollution exposure of other participants over the decade prior to when each one reached 72.

The researchers had to account for the different years in which individuals were enrolled in the study. Air pollution has dropped dramatically in the decades since the ACT Study began.

Noticeable differences in PM2.5 pollution levels can vary over short geographic distances. Shaffer said that in 2019, there was approximately 1 microgram per cubic meter difference in PM2.5 pollution between Pike Street Market in downtown Seattle and the residential areas around Discovery Park — places separated by about 6 miles. That seemingly small difference in exposure compounds into a 16% higher incidence of dementia.

Reducing brain health risks

“We know dementia develops over a long period of time,” Shaffer said. “It takes years — even decades — for these pathologies to develop in the brain, so we needed to look at exposures that covered that extended period.” This study examined 10-year average PM2.5 exposure in relation to dementia diagnosis — much longer than prior studies, which focused on 1-, 3-, or 5-year exposures.

The ACT Study’s strengths include having reliable address histories, regular participant follow-up, and standardized diagnostic procedures.

Sheppard is professor in the UW Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences as well as the university’s Department of Biostatistics. (Photo courtesy of Lianne Sheppard)

Sheppard is professor in the UW Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences as well as the university’s Department of Biostatistics. (Photo courtesy of Lianne Sheppard)There are many factors, such as diet, exercise, and genetics, that are associated with increased risk of developing dementia. Air pollution is now recognized to be among the key potentially modifiable risk factors. Shaffer’s results add to evidence, suggesting that air pollution has neurodegenerative effects — when neuron cells are lost and the brain loses function. Reducing exposure to air pollution could help reduce the burden of dementia.

“Our understanding of the role of air pollution exposure on health has evolved — we first thought it was pretty much limited to respiratory problems, then that it also has cardiovascular effects, and now there’s evidence of its effects on the brain,” said Lianne Sheppard, Ph.D., senior author and UW professor.

“Over an entire population, a large number of people are exposed,” Shaffer said. “So, even a small change in relative risk ends up being important on a population scale. These data can support further policy action on the local and national level to control sources of particulate air pollution.”

Citations:

Shaffer RM, Blanco MN, Li G, Adar SD, Carone M, Szpiro AA, Kaufman JD, Larson TV, Larson EB, Crane PK, Sheppard S. 2021. Fine particulate matter and dementia incidence in the Adult Changes in Thought Study. Environ Health Perspect 129(8):87001.

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Brayne C, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Costafreda SG, Dias A, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Kivimäki M, Larson EB, Ogunniyi A, Orgeta V, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N. 2020. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 396(10248):413–446.

(Original press release by Jake Ellison, UW News.)

Source link

factor.niehs.nih.gov