1. Introduction

As the global population continues to grow, the demand for protein also continues to rise [

1]. Technological advances have enabled the production of highly customizable and versatile materials with applications in many areas of sustainable food systems. Because of this, knowledge of the functional properties and characteristics of food ingredients has become increasingly important. Finding innovative ingredients and/or processes (e.g., 3D bioprinting) to improve the functional properties (e.g., emulsification, foaming, gelation, water- or oil-holding capacity) of foods is essential. A promising potential source of sustainable functional food ingredients are microorganisms such as filamentous fungi. Fungi represent potentially low-cost and eco-friendly materials that grow rapidly and may be cultivated on diverse substrates including organic byproducts of agriculture and food processing industries [

2]. Many fungi possess relatively high protein contents of up to 45% of the total biomass [

3] and fungal biomass fractions have been found to possess biochemical compounds with high functional properties [

4,

5]. For instance, centrate co-products of the mycoprotein Quorn

TM fermentation process (using filamentous fungus

Fusarium venenatum) containing mycelial aggregates, proteins, phospholipids, chitin, nucleotides, and other cell membrane and cell wall constituents were found to display useful rheological, emulsifying, and foaming properties [

4,

6].

Fungi have also been used as bioink mixtures to add nutritional and functional characteristics to 3D-bioprinted constructs. Three-dimensional bioprinting is an emerging technique in food manufacturing that creates precise 3D shapes with customizable dimension/shape, flavor, texture, and nutritional profiles [

7,

8,

9]. The technology could be capable of providing personalized nutrition, delivering sensitive/easily degradable bioactive compounds, modifying food textures (e.g., for individuals suffering from dysphagia), printing 3D foods in remote locations (e.g., astronauts or soldiers) [

7,

9,

10,

11]. Three-dimensional bioprinting also has significant potential in the creation of cultivated meat and other pure or hybrid alternative protein products [

10,

12,

13,

14]. Filamentous fungi have been utilized in 3D food bioprinting applications for a variety of functions making use of their unique morphological structure and composition. Wang and Liu [

15] used an addition of 4.18% shiitake mushroom powder to printable bioinks which comprised wheat gluten (10.45%), Tween-80 (1.39%), water (65.00%), cocoa butter (2.32%), starch from potato or wheat (4.64%), protein isolate from soy or pea (10.45%), and sodium alginate (1.57%). In another study, black fungus (

Auricularia auricula) was used to create gels for dysphagia patients utilizing a water-based solution of black fungus powder with additions of arabic gum, xanthan gum, and k-carrageenan gum as stabilizer components [

9]. Santhapur et al. [

16] utilized fungal mycoprotein (mycelium) and potato protein to create hybrid food products that made use of the inherent fibrous nature of the mycelium (mimicking muscle fibers) and the physical gelling nature of the potato protein to create meat-like structures and textures. Living fungi have also been used to create self-healing packaging materials with bioinks composed of agricultural feedstock inoculated with mold-type fungus, which after initial colonization, was reduced in particle size and added at 20% to a mixture of water and 4% psyllium husk powder, printed, and observed for re-colonization behavior [

17].

Hydrogels are important materials for foods and the formation of a 3D structure or scaffold is useful for bioprinting applications. Gelatin and sodium-alginate are popular hydrogel materials [

18] and where sodium-alginate is principally derived from brown algae, commercial gelatin is almost exclusively produced from animal-derived sources, which limits its application in alternative protein products [

19,

20]. Fungal-derived chitin and chitosan have been used in the creation of hydrogels [

21], but the process of extracting chitin followed by the deacetylation to chitosan can be arduous, and the resulting material may lack adhesion factors necessary for the attachment of animal cells in cultured meat applications [

22]. On the other hand, fungal protein extracts exhibit native attachment factors for animal cells [

23]. Protein extracts from filamentous fungi are a compelling fraction to explore for functional properties since protein extracts from plants and animals have found use in many food products due to their emulsification, foam formation, water-holding capacity, oil absorption, and gelation properties [

24]. These alternative protein isolates include insects [

24], soy protein [

25], and pea protein [

26], among others. However, the utilization of fungal protein extracts for the development of novel food products is underexplored. Edible fungal species protein contents can range from 9 to 52% protein, compared to that of grain legumes of 18–34%, cereal grains and pseudocereals of 8–11%, oilseed by-products (e.g., press cakes or solvent-extracted flours) of 45–65%, and green biomass (leaves, seaweed, microalgae, aquatic plants) of 12–70% [

3]. Green biomass, while high in protein content, contains mainly structural and biologically active proteins [

27] with a low shelf-life [

28], low extraction yields/purity [

3,

29], a presence of off-flavors [

29], and lower digestibility [

30]. Fungi can be grown on agricultural by-products with high efficiency, are commonly used in foods, and can display high Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Scores (PDCAAS; e.g., mycoprotein from

F. venenatum of 0.91) [

3,

31,

32]. Certain fungal strains have also demonstrated high globulin contents, such as

Pleurotus ostreatus, with 62% of its total protein content (24.7%), which indicates promise for use as a gelling agent [

33].

Auricularia auricula-judae has water soluble protein—polysaccharide that can act as a food thickener by improving texture and modifying starch gelatinization and gluten structure [

34].

Filamentous fungi represent promising functional materials for future foods. However, there is currently a gap in knowledge on the functional characteristics of fungal extracts and the procedures required for applying such materials in additive biomanufacturing and cellular agriculture applications. Therefore, this study’s objectives were to (1) develop processes to create functional fungal protein extracts from different fungal strains, Aspergillus awamori, Pleurotus ostreatus, Auricularia auricula-judae, and evaluate their characteristics, and (2) quantify the printability of the resulting fungal gels for the creation of structured food precursor materials.

4. Conclusions

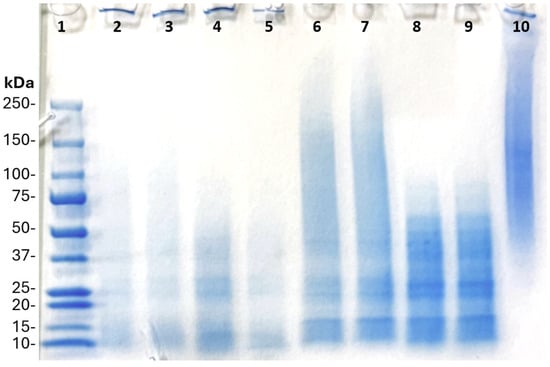

The fungal materials considered in this work are promising materials for hydrogel formulation. They were rich in protein, and that protein was easily extracted using isoelectric point precipitation to acceptable purity. The protein extracts of A. awamori and P. ostreatus were found to contain characteristics like disulfide bonds that contribute to protein gelation. FT-IR analysis confirmed the reduction in C-H, N–H, and C–O functional groups in protein extract samples, all of which are groups found in the structure of chitin, the cell wall material of fungi. The flour samples had on average a larger particle size than the protein extracts, but all had overall negative zeta potential. The fungal materials were able to form a gel that was 3D printable with only water, pH adjustments, and heating steps. Formulations of 15–25% protein extract and flour demonstrated shear-thinning characteristics required for 3D printing. Despite substantial textural differences, all the mixtures were able to form gels at 20% inclusion rates. The best performing sample for 3D printing was the P. ostreatus protein extract at 25% inclusion. Other samples like the A. awamori protein extract and P. ostreatus flour also printed acceptably at 25%, but did not perform as well in texture profile (TPA) measurements. P. ostreatus flour performed the overall worst in all categories for desired characteristics of alternative protein products, and A. awamori protein extract was less hard and gummy compared to P. ostreatus protein extract. A. awamori protein extract at 25% was far more resilient than other samples and produced higher quality prints than the A. awamori flour.

This work illustrates a potential use for fungi as a future food additive. Studies covering fungal flours and protein extracts as food ingredients are rare in the literature and there is a need to investigate other functional properties of these materials considering the wide diversity of fungi species available for sustainable food applications. It is recommended that future work consider the optimization of process parameters (ionic strength, pH, cell wall disruption, etc.) during extraction and gelation and to test different additive materials (e.g., sodium-alginate, transglutaminase) which may improve the strength or reduce the inclusion rate of the gels. Other factors like color were not optimal for food applications with the samples utilized in this study, so bleaching of the materials and observing effects on gelling behavior and printing performance is needed. Overall, this study points towards promising applications of fungal protein extracts as alternative protein food ingredients.