1. Introduction

China’s internal migrant population, also referred to as a floating population, are individuals who have relocated from their registered household residences to more developed regions within the country [

1,

2]. This movement is primarily driven by the pursuit of urbanized lifestyles, better employment opportunities, and improved economic conditions [

3,

4]. Over the past few decades, due to China’s rapid economic growth and urbanization progress, the size of the internal migrant population has expanded significantly. Unlike external migrants who constitute a relatively small proportion of the total population due to strict policy controls on migration into China, internal migrants have unrestricted mobility within the country’s geographical boundaries, which contributes to their significantly larger population size [

5,

6]. Recent census data indicate that China’s internal migrant population has exceeded 375 million, accounting for 27% of the total population, with an average age of 43 years, demonstrating a rising trend in both size and age [

7,

8]. Consequently, the health status of this community is critical to China’s health prosperity.

Despite their large numbers, members of the internal migrants are often considered non-permanent residents in their destination areas under China’s household registration system (the “Hukou” system) [

1]. As a result, substantial disparities exist in the public health services available to them. Compared to the local residents, these internal migrants face lower health awareness and restricted access to healthcare services, primarily due to social inequalities [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Additionally, their limited protection under healthcare insurance further exacerbates their vulnerability, contributing to significant public health challenges, such as the management of chronic diseases [

14,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The “healthy migrant effect” suggests that social integration can be a key determinant of health outcomes for migrants [

21,

22,

23]. The degree to which the migrants integrate into the local society may influence their living habits, dietary patterns, health awareness, and service utilization. However, research indicates that the social integration among China’s internal migrant population remains at a relatively low level [

24]. Social integration for this group tends to only meet their basic needs, without sufficient mechanisms to support deeper integration into the local communities. Studies show that higher levels of social integration are associated with improved mental health, better health awareness and healthcare service access among the internal migrant population in China [

25,

26,

27]. Yet, evidence regarding the impact of social integration on chronic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, remains limited.

Hypertension and diabetes are two major non-communicable diseases (NCDs) affecting the Chinese adult population, with serious implications for their quality of life and life expectancy [

28,

29,

30]. The complications arising from these conditions, such as cardiovascular and renal issues, are leading causes of mortality in China and impose a heavy burden on the individuals, families, and the national healthcare system [

30,

31,

32]. Research has shown that 15% of the internal migrant population suffers from hypertension and 5% from diabetes [

33,

34]. Although these rates are lower than those of the general population, the unique challenges faced by the internal migrant population—such as poor disease management due to their transient lifestyle and limited healthcare access in the inflow areas—amplify the health risks they face. These chronic conditions present a substantial challenge not only to individuals but also to the broader healthcare system, with insufficient supporting evidence and policy measures in place to address this growing issue. This study aims to investigate the association between social integration and chronic disease prevalences of the internal migrant population in China, focusing on hypertension and diabetes.

4. Discussion

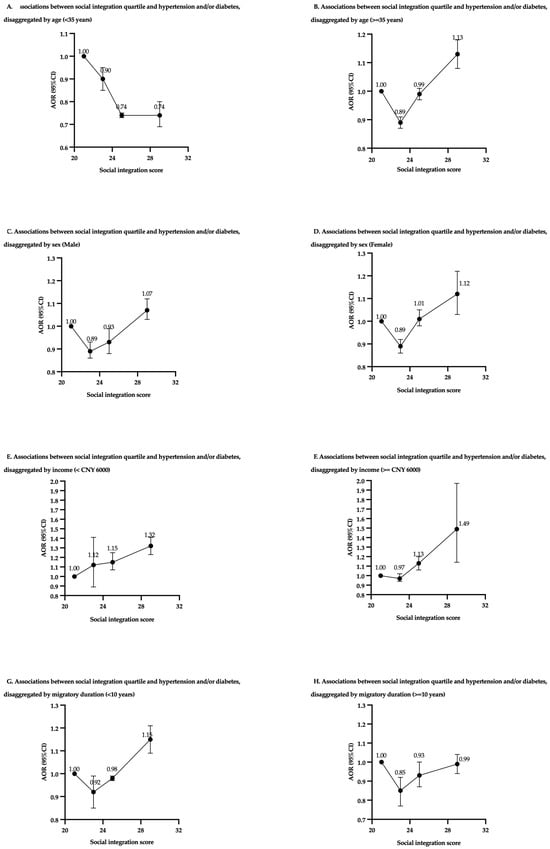

This study investigated the association between the level of social integration and the prevalences of hypertension, diabetes, and combined chronic diseases among the internal migrant populations in China. Interestingly, the results indicated that the medium level of social integration was associated with a reduced likelihood of reporting chronic conditions, while those with the highest or lowest levels of social integration exhibited an increased likelihood of having hypertension, diabetes, or either disease. Additionally, further analysis revealed effect modifications in the relationship between social integration and the prevalences of chronic disease by various factors, including age, sex, income, and duration of migration.

Overall, our research highlighted that internal migrant populations with the highest level of social integration generally exhibited the greatest likelihood of developing hypertension, diabetes, or both conditions. In contrast, those with medium levels of social integration had a relatively lower burden of chronic illnesses. This finding aligns with the “healthy migrant effect” observed in international migrant populations [

41]. A study of Chinese immigrants in Italy found that immersing into local culture was linked to a higher prevalence of hypertension and type 2 diabetes [

42]. A similar study on Chinese American immigrants showed better cultural adaptation was significantly associated with elevated blood pressure [

43]. Additional studies demonstrated that greater acculturation among immigrants increased the likelihood of hypertension, diabetes, and the figure could be doubled among certain immigrant communities [

44,

45,

46]. Similar to international migrants, the internal migrant population in China typically moves from less developed to more developed regions, pursuing better living conditions, higher incomes, and less physically demanding jobs [

47,

48,

49]. These changes often lead to altered dietary habits with increased calorie intake, reduced physical activity, and more sedentary lifestyles, which can increase the probability of having chronic diseases [

50,

51,

52]. Internal migrants with the lowest levels of social integration showed higher rates of chronic diseases, likely due to the stress of adapting to a new environment. Conversely, those with the highest levels of integration had the greatest burden of hypertension and diabetes, possibly because they had better access to healthcare and were more likely to be diagnosed. However, the pressure to fit in and maintain larger social networks may also cause stress, negatively impacting their health [

53]. As several studies suggested, the effects of an individual’s wider social network on health are barely comparable to that of intimate personal relationships, which is much more beneficial to health [

54,

55,

56].

Further analysis revealed different trends in the relationship between social integration and chronic disease prevalences across different age groups within the internal migrant populations. Among respondents under 35 years old, higher levels of social integration were consistently associated with a lower prevalence of chronic diseases. However, for those aged 35 and above, social integration exhibited a U-shaped relationship with chronic disease prevalence, with the highest level of integration corresponding to the greatest prevalence. Younger internal migrants are generally more proactive in adapting to their new environment [

57,

58]. Compared to the older internal migrants, increased social integration means that they may have greater access to services and are able to seek more actively for health education resources [

59,

60,

61]. In contrast, older internal migrants in China often relocate to assist their adult children who reside in the inflow region, or they are the first-generation internal migrants themselves [

49,

62]. They need to provide more physical or financial support to their families, often at the expense of their own time and money, which can lead to a passive social integration pattern. Alternatively, when the elderly internal migrants need assistance to access to healthcare services, their children are often unable to provide companionship and care because they are in school or work, so that the senior internal migrants cannot receive timely and appropriate diagnosis and treatment due to lack of intergenerational support [

63,

64]. In a typical society in China, where social and community support is not as well established as traditional family care, higher levels of social integration alone could not provide close support like family members, and may impose additional stress, thereby increasing the likelihood of having chronic diseases in this group [

65,

66,

67].

The relationship between social integration and chronic disease prevalences in male and female internal migrant populations both follow a U-shaped pattern, with a medium level of social integration offering stress-buffering benefits for both. However, women experience a steeper curve and a narrower range of the protective effect from social integration. This may be a result of different integration patterns between sexes [

68,

69]. Divney et al. discovered that female immigrants with higher acculturation had a 50% higher proportion of having hypertension compared to those with lower acculturation, while the likelihood for male immigrants increased 15% [

45]. Similarly, Modesti et al. found that acculturation nearly doubled the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among female Chinese immigrants in Italy, with no significant impact on men [

42]. A study of immigrant women from Mexico and the Middle East has shown similar results [

70,

71]. These disparities may arise from the traditional role for different sexes, which places greater family care responsibilities on women, as well as barriers to social integration, such as gender discrimination. At the migration destination, male migrants tend to build broader external social networks, often through work, while women typically maintain smaller, family-centered networks [

68,

72,

73,

74,

75]. As women reach higher levels of social integration, the exhaustive effort to balance family and social responsibilities may exert excessive burden and compromise their health [

76,

77,

78].

Meanwhile, irrespective of the internal migrant population’s income level, higher levels of social integration are significantly associated with a higher likelihood of developing chronic diseases. This may be attributed to the income disparity between the migrant community and local residents, as the study found socioeconomic inequality negatively influences the health of internal migrants with equivalent levels of social integration compared to local residents [

25]. The development and maintenance of social networks is one of the strategies used by the migrant population to increase income at the inflow region; however, they often have to endure the down-side of frequent social interactions, such as picking up unhealthy social behaviors including smoking, drinking, and intaking high-calorie food which can contribute to chronic disease development [

25,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84].

Finally, in the disaggregated analysis by migration duration, better social integration was associated with higher prevalences of chronic diseases among individuals with a migration duration < 10 years. In comparison, this trend was not significant among those who have migrated ≥ 10 years. However, in the linear regression analysis, it was found that internal migrants who have migrated ≥ 10 years have a significantly higher likelihood of having chronic diseases than those who have migrated < 10 years. We believe that this difference is due to the use of relative comparisons rather than comparisons of absolute values in the disaggregated analysis. Although no significant increase in the prevalences of chronic diseases was observed in the group whose have migrated ≥ 10 years, this may be attributed to the fact that other important factors, such as better social welfare and access to healthcare services, which may exert stronger effects on migrants of ≥10 years, could potentially undermine such an association.

Meanwhile, our findings regarding the association between social integration and chronic disease development disaggregated by migration duration are not in contradiction with the “healthy migrant effect” [

41]. However, previous migrant studies that investigated the “healthy migrant effect” were often limited by relying solely on time as a measure of migrants’ social integration [

43,

44,

45,

46,

85,

86,

87]. To address this limitation, this study employed a broader range of indicators, including participants’ subjective sense of integration and perceptions of social acceptance. Additionally, we conducted disaggregated analyses to examine how different subgroups and their social integration status may influence the likelihood of developing chronic diseases. While these indicators did not show a significant impact among the long-term internal migrants, future studies could benefit from incorporating more comprehensive dimensions, such as economic integration, social support, self-identity, or using standardized scales to comprehensively evaluate the relationship between social integration and health outcomes [

55,

88,

89,

90,

91].

Admittedly, this study also has several limitations. First, this study focuses on internal migrants in China. Given the unique characteristics of China’s household registration system and the relatively smaller differences in language, culture, race, and political environment among internal migrants compared to international migrants, the findings of this study may not be fully generalizable to international migrant populations. Moreover, as a cross-sectional analysis, it cannot establish causality between social integration and chronic disease prevalences. In addition, reverse causality may also occur due to the cross-sectional study design, as the internal migrants’ physical and mental health may affect their social participation and long-term settlement intention in the destination region, which are key aspects for social integration [

92]. While our study showed significant associations between social integration and chronic disease prevalences, the direction of the causality between social integration and health among the internal migrants shall be further explored by cohort studies. The social integration scale reflects subjective perceptions rather than actual community acceptance, and the reliance on self-reported data for hypertension and diabetes lacks objective measures like blood pressure and glycated hemoglobin levels. Moreover, the 2017 CMDS database contains the most recent data available for our study, which may present certain limitations in capturing the changing demographics of the internal migrant populations. However, as the Hukou system remains the decisive factor differentiating the internal migrants from local residents and has undergone no major reforms since 2014, we believe the large, representative sample from the 2017 CMDS database still holds significant relevance and provides valuable guidance to the understanding of the current situation. When updated data become available, future research should adopt longitudinal designs and incorporate more objective health and social integration measures to explore the changing dynamics and to establish their relationship with chronic disease prevalences.