3.1. Life Satisfaction in This Study

When considering all levels of income loss, there is an increase from 48.9% in the initial survey to 72.2% in the subsequent one, indicating that the economic impact of the pandemic on individuals worsened over time. However, when considering only acute economic impact, a slight decrease in the severity of the impact is noted, with 44.3% of respondents reporting acute economic impact in the second survey compared with 48.9% in the first survey. Also, in the initial phase of the crisis, 43% reported a reduction in working days, yet in the second survey, only 21.1% reported tangible harm to their professional work (including loss of working days). However, even two years into the crisis, 64.8% reported a rise in workplace stress. While this indicates a 10% decrease compared to the crisis’s onset, the figure remains notably high.

The intricate interplay between work and home life was significantly affected during the early stages of the epidemic, particularly due to closures and movement restrictions. Some 26.4% of respondents reported that their work–life balance was compromised at the outset of the crisis. However, by the beginning of 2022, there was a noticeable improvement, with only 12.5% expressing a continued work–life balance impairment. This shift suggests that individuals employed adaptation and coping strategies as the crisis extended, potentially contributing to a more stabilized work–home equilibrium over time.

Concerning healthy lifestyles, at the outset of the pandemic, following the stringent restrictions on movement, individuals perceived a more pronounced deterioration of lifestyle, with 21.4% reporting a less healthy lifestyle compared to 16.5% reporting a healthier lifestyle. However, a year and a half later, the trend reversed, with only 12.2% reporting a decline in healthy lifestyle compared with 14.9% reporting healthy lifestyle improvements since the outset of the pandemic. In contrast, decreased expectations for a healthy lifestyle slightly worsened from the first survey to the second (34.5% vs. 39.9%).

The prolonged impact of the COVID-19 crisis is evident in the sustained emotional and mental strain reported by approximately 48% of respondents in both surveys. This figure remained stable even as the restrictions were relaxed, highlighting the enduring challenges COVID-19 posed to the emotional and mental wellbeing of individuals.

The influence of the COVID-19 crisis on vacation patterns persisted even after the removal of many of the initial restrictions. At the crisis’s onset, 73.7% of respondents reported a negative impact on vacation patterns, and a year and a half later, this trend remained significant, with 66.8% noting adverse effects. Similarly, the negative impact on leisure patterns persisted throughout the pandemic, with a decrease of only 4.5% (69.6% to 65.4%) between the two surveys.

The adverse impact on social relations remained consistent, with approximately 55% reporting some adverse effects during both stages of the pandemic. During the initial stages of the crisis, relationships within the nuclear family experienced both positive and negative impacts in roughly equal proportions, with around a third (30–32%) reporting each. However, two years later, the impact shifted in a negative direction, as 35.5% of respondents indicated damage to nuclear family relations and only 17% indicated a positive impact of COVID-19 on nuclear family relations. The results show a similar trend with regard to extended family relations: at the crisis’s onset, negative impacts were reported by 44.4% of the respondents, while positive impacts were reported by only about half that number (23%). As of the beginning of 2022, the negative impacts remained relatively stable (46%), but the positive impacts decreased to 13.2%. Thus, even with the removal of restrictions, there was no immediate improvement in the reported negative effects on social relations and family relations, underscoring the enduring effects on interpersonal connections.

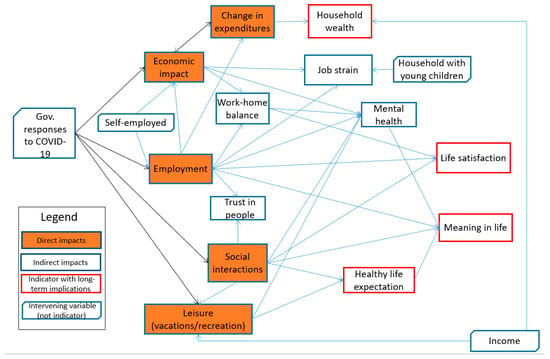

The overall picture that emerges is thus one in which economic losses, work–life imbalances, and adverse healthy lifestyle effects were largely mitigated once the restrictions were removed. The adverse effects on mental health and expectations for a healthy lifestyle and social contacts, including within the family, remained high even after the restrictions were lifted.

3.3. Factors Affecting Life Satisfaction over Time

The possibility of using ordinal regression was considered in order to avoid the loss of original information of the dependent variable (five categories instead of three). However, two main considerations led to the selection of the MNL procedure. First, it is more important for this study to understand the differences between unsatisfied and satisfied people regarding the tangible effects of the pandemic and to identify how the main factors explored affected life satisfaction rather than to understand differences among ordinal levels of life satisfaction. Second, from a methodological perspective, because the proportional odds assumption for ordered regression is violated in our data, we recoded the dependent variable into a categorial variable and used MNL regression models instead of ordinal regression.

3.3.1. The Cross-Sectional Results in the Three Models

One of the most significant findings of this study is that the control variable survey (time) has a prominent effect. The survey variable included in the “All” model (model 3) presents the strongest effect among all the variables explored in the different models. This finding is in line with the aim of our study, which is to explore the changes in life satisfaction in light of public developments such as vaccinations, ease of public restrictions, and relief measures. Specifically, respondents in Survey 1 are about seven times more likely to be unsatisfied with their lives than respondents in Survey 2. Almost the same result was obtained in the sensitivity analysis (in model 3, Exp B = 7.204 vs. the tested sensitivity model, Exp B = 7.543). That is, vaccination and the relaxation of restrictions increased life satisfaction.

The psycho-social effects observed in the models are related to individual perceptions of how the pandemic affects individuals, and social life and has a significant impact on the wellbeing of individuals. People who were emotionally affected due to the pandemic were significantly more likely to report lower levels of life satisfaction (above five times more than those less affected in Survey 1 and almost four times more than those less affected in Survey 2). Although this result is not surprising because of the close relationship between psycho-social individual perceptions and subjective wellbeing, the current analysis shows the prevalence of social and emotional aspects (comparing the odds ratio) over tangible aspects (such as the economic loss) as the major effect on life satisfaction during the pandemic. These findings are consistent with the findings in our previous study. In the Israeli context, it appears that disruptions to social life had a greater negative impact on life satisfaction than economic loss.

Other factors, such as unemployment (which primarily impacts economic loss but can also be linked to psychological distress), exhibit a decrease in life satisfaction in the “All” model (Model 3) and in Survey 2 (Model 2). Similarly, lower income levels show effects in Model 3 and Model 2 (only for the middle category of life satisfaction). Among the economic changes resulting from the pandemic, high stress at work emerges as the most significant and consistent variable across all models. Individuals experiencing high stress at work are almost three times more likely to report dissatisfaction with life in all three models.

3.3.2. Comparative Results—Differences Between Surveys

The second analytical approach involves examining differences between the two survey periods, namely Survey 1 and Survey 2. In Survey 1, factors such as medium-level income, economic hardship (linked to dissatisfaction), and using loans and savings were significant contributors to decreased subjective life satisfaction (with the exception of expenditure reduced). Conversely, in Survey 2, gender, unemployment, economic hardship (among those with moderate life satisfaction), harm from public transportation (PT), and reduced expenditure emerged as significant factors. These findings suggest that during the initial phase of the pandemic, economic concerns, particularly for the middle class and those with uncertainty about long-term financial stability, were paramount. However, the persistent effects observed in Survey 2 were particularly pronounced for unemployed individuals, indicating heightened employment anxieties for this group, as well as for individuals who reduced their expenditures and those with lower incomes. These cohorts likely harbored more pessimistic outlooks regarding their prospects for improvement amidst the prolonged pandemic crisis, thereby impacting their overall wellbeing. The significance of PT harm in Survey 2 (which was not observed in Survey 1) could be attributed to restrictions on public transportation services due to public health considerations, particularly in densely populated areas following lockdowns. This limitation affected employees and PT users who rely on these services for daily mobility needs, exacerbating their challenges.

Despite these differences, the models show a stable trend regarding high stress at work, probably due to the intrinsic uncertainty in the pandemic regarding the future and financial repercussions at the workplace. Similarly, the psycho-social effect is significant in the two models. However, this effect is reduced in Survey 2. This finding suggests that the impact of the initial shock of the population as a result of the pandemic in different areas (e.g., health anxiety, financial uncertainness, and social loneliness) was eased after vaccinations were available and restrictions were relaxed.

The findings further reveal that reduction in expenditure was statistically significant in both surveys, but in opposite directions. While Survey 1 shows that those with increased expenditures had slightly higher life satisfaction, Survey 2 shows that they had significantly lower life satisfaction than those without reduced expenditures. Individuals reporting a decline in expenditure tended to be more economically vulnerable, and their diminished reported wellbeing during the second survey could have potentially been influenced by a significant policy shift introduced by the Israeli Ministry of Finance in July 2021. This policy change substantially reduced the safety net and special COVID-19-related allowances that were designed to support unemployed and economically vulnerable populations during the pandemic (Israeli Ministry of Finance, 2021).

Source link

Fabian Israel www.mdpi.com