4.1. Italian Circular Economy Policies Scan

As a Member State of the EU, Italy has ratified all the European Directives to establish binding targets for specific sectors. For example, waste and energy management are regulated by specific directives at the European level, and therefore, targets have been transposed into Italian legislation. Five policies have been analyzed, directly and indirectly, targeting CE and the construction sector.

Italy has also adopted the National strategy for sustainable development, outlining the pathway to achieve the Agenda 2030 goals [

54]. It indirectly addresses CE since the topic is included in the strategy; an explicit link is made in the section dedicated to “Prosperity”, in which the document directly mentions the necessity of creating a new CE model aiming at a more sustainable and efficient use of resources, minimizing the negative impacts on the environment, thus fostering the progress of humankind. In this respect, the circular material use is calculated among the core indicators, intended as the percentage of secondary raw material used in production processes as well as the recycling rate. Other strategies decrease emissions and increase the efficiency of water management systems. Moreover, urban renovation is fostered, thus aiming at prolonging the lifetime of buildings. However, the regional governments are in charge of the application, and the CE is mentioned only when it comes to waste management in the regional strategies of sustainable development annexed to the document, thus confirming the sectorial (and limited) application of the concept currently adopted.

Specifically targeting the construction sector, a new decree specifies the end of waste criteria for C&D waste. It specifies to what extent C&D waste can re-enter the construction process. Moreover, the national legislative decree n.o. 152/2006 promotes waste prevention through a sustainable design, waste recovery, and recycling, as well as a technological system able to track the waste streams [

55].

In terms of CE policies, Italy is one of the EU countries that has a national strategy for the CE transition [

56], as foreseen in the mission 2 component 1—Sustainable Agriculture and CE—of the National Resilience and Recovery Plan (PNRR) [

57]. The roots of the CE Italian national strategy can be traced back to 2017 when, after public consultation, the document “Towards a circular economy model in Italy. Document of framework and strategic positioning” was published. The document aimed to provide an overview of CE and the Italian positioning on the topic, ensuring coherence with the goals of the Paris Agreement, the SDGs, and the European Union target. Among the objectives, the strategy is identifying new administrative tools to strengthen the market of secondary raw materials, making them competitive if compared to virgin raw materials (e.g., through public procurement and Minimum Environmental Criteria, end of waste, extended producer responsibility, fostering the product as a service, and sharing practices). Chapter 8 identifies the macro-objectives and specific objectives of the strategy together with a list of actions to be undertaken by 2035, divided into specific sectors, among which urban areas and territories are listed.

Italy also enacted the National Green Public Procurement Action Plan (2023) [

58] in which it is stated that all public procurement must comply with minimum environmental criteria (CAM). The CAM requirements are defined for the various phases of the public administration’s purchasing process with the purpose of identifying the best design solution, products, and services from an environmental point of view. Their systematic and homogeneous application makes it possible to prefer environmentally preferable products and produces a leverage effect on the market, inducing less virtuous economic operators to adapt to the new requests of the public administration. In Italy, the effectiveness of the CAM has been ensured by the transposition of the Action Plan in law (Legislative Decree 36/2023 article 57), which made the CAM application mandatory [

59]. The objective is to reduce the environmental impacts and promote a more sustainable and circular production and consumption model. At present, CAM have been adopted in 21 categories of supplies and assignments, among which the construction sector is included. The application of the CAM considers and supports the existing regulations, such as the directive related to the energy performance of buildings (2010/31/EU and subsequent modifications [

60]), the EU regulation about construction products (305/2011/EU and subsequent modifications [

61]), and the waste management directive (2008/98/CE and subsequent modifications [

62]). Concerning the integration of CE principles, a paragraph is dedicated to disassembly and end-of-life: it is stated that the project relating to new buildings, including demolition works and building reconstruction or renovation, requires at least 70% in weight of the building components subject to disassembly or deconstruction or other recovery operations. The threshold has to be demonstrated through a disassembly and selective demolition plan drafted by the applicant to the tender. Another requirement is related to the use of construction materials (e.g., iron, bricks, wood, concrete, insulation) produced with at least a pre-defined percentage of recycled materials. In addition to the minimum requirements, in the law, there are some additional criteria that, if guaranteed by the applicant to the tender, allow the collection of extra scores for the evaluation process. As an example, a premium score is attributed to the economic operator who decides to undertake a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Life Cycle Cost (LCC) study to assess the environmental and economic sustainability of the project as well as the use of Building Information Modeling (BIM) for the different phases of the construction.

Another document in force that indirectly targets CE is the National Plan for the Ecological Transition [

63]. The Plan was approved in 2022 by the Ministry of the Ecological Transition, and its general aim is to reach climate neutrality by 2050 and reduce intermediate target GHG emissions by 55% by 2030. Regarding CE implications for the construction sector, the Plan fosters the substitution of materials with bio-based ones (e.g., promoting the use of wood in construction). In terms of energy efficiency, the Plan promotes the design of Net Zero Energy Buildings and the integration of renewable energies in the energy demand of residential buildings. Strategy no. 8 is about the promotion of CE, and it includes a focus on the construction sector in which the strong relation between the CE and the energy efficiency is acknowledged. Secondary raw materials, eco-design, light and durable materials, recyclable materials, and design for disassembly are all crucial elements of the strategy. The target for building renovation is set at 2%/year, and another important aspect highlighted is the need to introduce renewable energies.

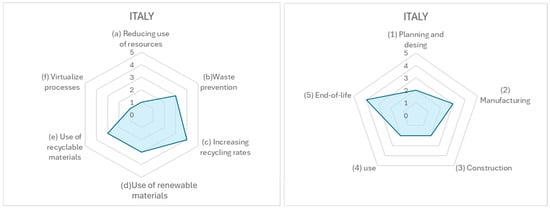

Figure 1 synthesizes the phases of the construction value chains that are mostly impacted by Italian policies and the CE criteria that are considered. End-of-life is the main life cycle stage addressed, while increasing recycling rates is the dominant CE strategy.

4.2. Germany Circular Economy Policies Scan

Six policies have been analyzed in detail, two of those highly relevant for CE transition and of a binding nature: the new German Closed Cycle Management Act (Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz, KrWG) [

64] and the New Buildings Energy Act (Gebäudeenergiegesetz, GEG) [

65]. Both impact all the construction value chain phases and address almost the totality of CE actions, except for “virtualize” processes. The waste management aspect, based on the closed-loop concept and disposal responsibilities, is not new in Germany. The relevant policy has been adopted for more than 20 years. In 2013, there were 339.1 million tons of waste produced in Germany with a total recycling rate of 79%, of which 202.7 million tons are C&D waste. The new German Closed Cycle Management Act aiming at transforming waste management in Germany into resource management came into force on 1 June 2012, which has raised public awareness of closed-cycle waste management even more [

66].

The New Buildings Energy Act [

65] came into force on 1 November 2020, which replaces and unifies the German Energy Saving Act (Energieeinsparungsgesetz, EnEG) [

67], the German Energy Saving Ordinance (Energieeinsparverordnung, EnEV) [

68], and the German Renewable Energies Heat Act (Erneuerbare-Energien-Wärmegesetz, EEWärmeG) [

69]. The new law will also be supported by other existing laws and standards [

70].

The other binding tool that is relevant for the CE transition, even though not directly, is the Germany Federal Climate Change Act [

71]. All the phases of the construction value chain are impacted by promoting the reduction of resource use, waste prevention, and the use of renewable materials. The same CE actions are fostered by the other two non-binding documents. The Germany Climate Action Plan 2050 [

72] and the Germany Energy Concept [

73] indirectly foster CE transition of the built environment since the first one aims to cut up to 67% emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 [

74], while the second one promoted the reduction of 80–95% of the primary energy demand compared to 2008 [

75]. Furthermore, several voluntary certification frameworks have already been established globally to quantify the environmental impact of specific buildings and reduce it over time. These frameworks include world-renowned LEED and BREEAM certification frameworks, and the system particularly made for the German market, the DGNB (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen) certification system.

Other incentives in Germany that are worth mentioning include but are not limited to subsidies provided at the federal and state level, such as the following [

76]:

Subsidies provided by the German Credit Institute for Reconstruction with the KfW 55 loan for passive houses;

Several states have set up/planned a subsidy per ton of biogenic carbon used (e.g., North Rhine-Westphalia, Berlin, Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg).

In

Figure 2, it is shown that the most diffused CE practices are the reduction of the use of resources, being implemented in all the analyzed documents, together with the promotion of the use of renewable/renewable materials. Virtualization practices are not fostered by any policy. When it comes to the construction value chain, there is a holistic thinking of the transition, since 5 out of 6 policy documents are considering all the phases of the value chain.

4.3. U.S. Circular Economy Policies Scan

As mentioned in the background, CE is still in its infancy in the U.S., and federal policy has been largely impacted by the current administration. However, given the relative autonomy of U.S. states and cities and the vast geographical territory of the country (which results in a variation of local infrastructure and different levels of CE implementation), in this paper, we analyze strategies at a city scale. Several U.S. cities have created action plans and targets to foster a CE and decarbonize their industry sectors, including construction. For example, the City of Charlotte, in North Carolina, developed the Sustainable and Resilient Charlotte by 2050 Resolution, which strives to source all the energy use in the local building sector from zero-carbon sources by 2030 [

77]. In addition, in 2018, the “Circular Charlotte” report explored how Charlotte could start implementing a strategy to become the first circular city in the U.S. Similarly, the City of Phoenix, in Arizona, created the Phoenix’s Zero Waste and Circular Economy roadmap, seeking 50% waste diversion by 2030 and zero waste by 2050 through increasing the reuse and recycling rate of materials [

78]. The City of Austin, in Texas, developed the Austin Resource Recovery plan with the goal of reaching zero waste by 2040. The plan includes the Circular City Program, which aims to change citywide policies, create CE pilot projects, and implement zero waste goals for city facilities [

79]. San Francisco, in California, highlighted CE strategies for building material management in its San Francisco Climate Action Plan. The Plan includes green building requirements for City facilities, such as a waste limit per square foot of building area, the use of Environmental Product Declarations, and the requirement of whole building life cycle assessments [

80].

C&D waste is the largest single waste stream ending up in landfills in many U.S. cities. C&D waste can be prevented through circular building strategies such as design for disassembly and material reuse. Designing for disassembly means planning for future deconstruction and material reuse from early design phases. Existing buildings that were not designed that way can still be deconstructed, but a much higher rate of material reuse and recycling can be achieved through design for disassembly [

81]. Although very few buildings in the U.S. (and worldwide) have been intentionally designed for disassembly, some U.S. cities have been implementing deconstruction ordinances as part of their CE policies. San Francisco and Los Angeles are part of the Clean Construction Declaration shared by the C40 cities, a group of large cities worldwide that share a commitment to acting on climate change. The commitments include requiring the deconstruction of buildings by 2025 and advancing design for disassembly and Building as Material Banks by 2030 [

82].

Portland, in Oregon, pioneered deconstruction regulations by requiring certain buildings to be fully deconstructed [

83]. The policy started in 2016 and is limited to single-family residential units built in 1940 or earlier. In Milwaukee (Wisconsin), a deconstruction ordinance dating from 2018 mandates deconstruction for historic buildings or structures built in 1929 or earlier [

84]. The City of San Antonio (Texas) adopted a similar ordinance in 2022, requiring all small-scale residential units built prior to 1920 to be deconstructed [

85]. The City of Palo Alto (California) went one step further and started requiring the deconstruction of all residential and commercial buildings in 2020 [

86].

The results show that all eight city-level policies included in the analysis address waste prevention and recycling rates, while none directly acknowledge the digital technologies needed for virtualizing CE processes. Due to the increasing number of deconstruction ordinances, U.S.-based CE policies focus heavily on the end-of-life phase of the construction value chain (

Figure 3).

4.4. Japanese Circular Economy Policies Scan

In Japan, while there have been laws aimed at promoting recycling and reuse, the Basic Act on Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society serves as the central legal framework that incorporates the comprehensive concept of a CE [

42,

43]. This law aims to shift away from a mass production, mass consumption, and mass disposal economic model. It promotes the efficient use of resources and recycling throughout the entire lifecycle, from production and distribution to consumption and disposal. Through these measures, it seeks to reduce resource consumption and establish a material-cycle society with minimal environmental impact.

Building upon this framework, this section analyzes five key laws and plans closely related to promoting CE in Japan’s construction sector, as well as four additional laws and policies that have a significant impact.

Japan’s CE policies in the construction sector have been progressively strengthened, as outlined in the Fourth Fundamental Plan for Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society (2018) [

87] and the CE Roadmap (2022) [

48], which was developed to monitor progress. The CE Roadmap, in particular, sets forth specific measures aimed at achieving a circular society by 2050. These include expanding the use of construction waste, improving the efficiency of raw material usage, promoting an environmentally conscious design, extending building lifespans, forming and maintaining high-quality social infrastructure, and utilizing reusable construction materials. Subsequently, in August 2024, the Fifth Fundamental Plan for Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society was approved by the Cabinet, positioning the transition to a CE as a national strategy and setting targets for 2030 [

44]. This plan specifies improving the quality and expanding the use of recycled construction materials, promoting compact and resilient urban development, and reducing disaster-related building waste. A new CE Roadmap, based on the Fifth Fundamental Plan, is expected to be developed in the near future.

Key laws that serve as the foundation for implementing CE in the construction sector include the Act on Recycling of Construction Materials [

88], the Act on the Promotion of Effective Utilization of Resources [

89], the Act on the Rational Use of Energy (Energy Conservation Act) [

49], and the Act on Promoting Green Procurement (Green Purchasing Act) [

90]. These laws play a crucial role in promoting resource circulation and reducing environmental impact within the construction sector, thereby supporting the formation of a sound material-cycle society.

The Act on Recycling of Construction Materials [

88] mandates that construction contractors properly sort waste materials such as concrete, asphalt, and wood generated from demolition and construction activities. The law aims to achieve high recycling rates and reduce environmental impact through the reuse and recycling of these materials.

Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism has committed to the steady implementation of the Construction Recycling Promotion Plan 2020 [

91,

92] as part of its Environmental Action Plan [

93]. The plan notes that the recycling rate for construction waste, which was around 60% in the 1990s, had reached approximately 97% by fiscal year 2018, marking a transition from a growth phase to a maintenance and stabilization phase. Moving forward, the focus will shift toward improving the quality of recycling, specifically by enhancing the value of recycled materials and promoting the use of high-value-added recycled products.

The Act on the Promotion of Effective Utilization of Resources aims to promote the recycling and reuse of construction materials and recycled resources [

89]. It mandates construction contractors to utilize recycled resources and recycle by-products for certain specified construction materials. Specifically, it encourages the use of recycled materials such as crushed concrete and asphalt concrete, as well as the recycling of soil and crushed concrete generated during construction activities. This law seeks to enhance the efficient use of resources in the construction sector.

The Act on the Rational Use of Energy [

49] was revised in April 2023, mandating compliance with energy efficiency standards for nearly all newly constructed buildings. This revision contributes to reducing energy consumption in buildings and lowering greenhouse gas emissions.

The Act on Promoting Green Procurement mandates national and other public institutions to procure environmentally friendly goods and imposes a duty of effort on local governments [

90]. This promotes the use of eco-materials and recycled resources in public sector projects, contributing to the reduction in environmental impact.

Looking more broadly at laws and policies related to the construction sector, the Waste Management and Public Cleansing Act (Waste Management Act) [

94] and the Government’s comprehensive plan based on the Law Concerning the Promotion of Measures to Cope with Global Warming (Global Warming Countermeasures Plan) [

95] are noteworthy. The Waste Management Act establishes a management framework for construction waste from generation to final disposal, forming the basis for proper waste management within the construction sector’s CE efforts.

The Global Warming Countermeasures Plan [

90], formulated in 2021, aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 46% from 2013 levels by fiscal year 2030, with a commitment to further pursue a 50% reduction. The plan outlines the direction of CE policies aimed at achieving carbon neutrality, including the expansion of construction waste utilization, improvement in the efficiency of raw material use, promotion of an environmentally conscious design, and extension of building lifespans.

The Green Growth Strategy [

96] outlines action plans and concrete projections for 14 key sectors expected to drive growth from both industrial and energy policy perspectives. These sectors include next-generation renewable energy, hydrogen industries, automotive and thermal storage battery industries, semiconductor and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) industries, civil infrastructure, housing and building industries, and resource recycling-related industries. For housing and buildings, the strategy emphasizes strengthened regulatory measures, such as mandating compliance with energy efficiency standards, and the promotion of zero-energy homes and buildings. Additionally, the government supports corporate efforts through various means, including budgetary allocations, tax incentives, financial support, regulatory reforms, international cooperation, the promotion of initiatives in universities, the hosting of the 2025 World Expo, and the establishment of a youth working group.

The Circular Economy Vision 2020 [

97] outlines the challenges and strategic directions for transitioning to a CE. Against the backdrop of the limitations of the linear economic model, advancements in digital technologies, and increasing demands from markets and society for environmental considerations, the vision aims to shift from the 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) as environmental activities to CE as an integral part of economic activities. It also promotes the development and global deployment of circular products and business models, advocating for companies to voluntarily advance their management and business strategies. Additionally, the vision emphasizes the long-term goal of reconstructing a resilient circular system.

The Growth-Oriented Resource Autonomy Strategy [

98] presents a comprehensive policy package aimed at reconstructing resource circulation industrial policies to achieve autonomy and resilience in Japan’s domestic resource circulation system while capturing international markets. In the context of the construction sector, the strategy highlights a resource-efficient design, including the use of recycled and renewable resources (such as wood and bio-based materials). Instead of setting detailed standards at the national level, the government supports private-sector standardization efforts, encouraging companies to voluntarily establish and disclose quantitative targets.

Thus, the promotion of CE in Japan’s construction sector is progressively supported by a framework centered on the Basic Act on Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society and reinforced by related laws and policies. This framework enables the steady implementation of concrete practices across various stages of the construction value chain, including the proper disposal and improved recycling rates of construction waste, the promotion of recycled material use, enhancements in energy efficiency, an environmentally conscious design, and the extension of building lifespans.

Figure 4 synthesizes the phases of the construction value chains that are mostly impacted by the above-mentioned Japanese policies and the CE criteria that are considered.