1. Introduction

Health literacy (HL) has been a growing issue since the term was first used in 1970 [

1]. There are many definitions of HL. Malloy-Weir, with colleagues [

2], counted as many as 250 of them, and there was considerable variation between them. This is because the concept of HL has evolved over time to meet the constant challenges of society. Currently, the definition of HL is broad and still expanding and includes information-seeking, decision-making, problem-solving, critical thinking, and communication [

3], as well as a variety of social, personal, and cognitive skills that are essential for preserving, protecting, and enhancing personal and public health [

4]. The HL can significantly influence a person’s health [

5]. Studies have shown that insufficient HL can lead to lower adherence to medication regimens [

6], lower knowledge of diseases and their management [

7], worse treatment outcomes [

8], and poorer quality of life [

7,

9]. Compared with those with adequate HL, those with insufficient HL are less likely to participate in preventive programs [

9], have a higher risk for hospitalization [

10], and have an increased risk of mortality [

11]. This leads to the inefficient use of health services, increased healthcare costs, and health inequalities [

6,

12].

HL in children and adolescents is often described as an individual characteristic that shows how children and adolescents receive, perceive, evaluate, and communicate information about health and how it is used to make health-related decisions and adjust behavior [

13]. Individual cognitive skills such as reading, writing, critical thinking, or information processing skills are the most emphasized [

14], but factors such as self-reflection, self-efficacy, motivation, communication skills, or specific technical skills are often also included [

13,

15]. Paakkari and Paakkari [

16] define HL in children and adolescents as a result of school health education that assesses students’ abilities in a given situation. Other authors emphasize how health-related information is used and applied in different life situations and social settings [

1]. Studies have shown that inadequate HL among adolescents is associated with lower engagement in health-promoting behaviors [

17], lower self-esteem [

18], and poorer quality of life [

14,

19]. Adolescents with high levels of HL are more likely to take responsibility for their health [

13,

20], and they are more effective in accessing health-related information and using this knowledge to reinforce positive health behaviors [

13]. High HL level is associated with a lower rate of being overweight [

21] or underweight [

22], more leisure-time physical activity [

23,

24], enhanced nutritional and oral hygiene practices [

21], lower tobacco and alcohol consumption [

17,

24,

25,

26], better sleeping habits [

26], better stress management [

27], and higher academic achievement [

28]. Adolescents with high levels of HL also perceive their health better than those with lower HL [

29,

30,

31].

Studies in the last decade have revealed that a more in-depth analysis of HL is needed because of its value in improving adolescent health [

17,

32]. This requires valid and practical tools for measuring HL that allow objective and continuous assessment of adolescents’ HL and progress monitoring. HL assessment tools are validated for use in the adolescent population, but most tools measure only selective domains. Several systematic reviews have also shown this. Fleary and colleagues [

17] identified seven HL measurement instruments and reported that these tools usually assess functional and media HL when measuring the relationship between adolescent HL and health behavior. Guo and colleagues [

33] identified 29 HL measurement instruments for children and adolescents aged 6–24 years and emphasized that researchers have focused mainly on the functional domain. A systematic review by Okan and colleagues [

34] identified 15 generic HL measurement instruments for children and adolescents and reported that measuring HL among children and adolescents is particularly difficult for several reasons. First, there is currently no universally recognized model or definition of HL, and it is highlighted as a significant weakness affecting the development of comparable methods to measure the concept accurately. Second, children’s cognitive and social development varies dramatically between age groups; therefore, it is essential to tailor concepts and their operationalization on the basis of age and developmental stage, considering the capabilities of children at various stages of childhood and adolescence. Researchers highlighted the need for further research to improve HL measures for children and adolescents [

17,

33,

34].

In Lithuania, there is a lack of HL research; only a few HL surveys have been conducted in the adult population [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. The HL of children and adolescents was measured using a brief Health Literacy for School-Aged Children (HLSAC) instrument with participants aged 13–16 years [

41]. It should be noted that the HLSAC scale was created and assessed as part of the WHO Child and Adolescent Health Study, known as the HBSC (Health Behavior in School-Aged Children) [

31]. Thus, this questionnaire is designed to measure the HL of younger adolescents. Although this questionnaire has been used with older adolescents (16–19 years) in other countries [

42], data on its validity in this age group are lacking. No studies have measured HL in adolescents over 16 years of age in Lithuania. Although the HLS-EU-Q47 instrument, developed and validated by the HLS-EU consortium [

43] to assess HL in individuals aged 15 and older, has been translated into Lithuanian [

38] and could be used to evaluate the HL of adolescents aged 15 and above, its application among this age group remains uncertain. Several studies exploring the reliability of the HLS-EU-Q47 for measuring HL in adolescents over 15 years of age have questioned the validity of the instrument for this age group and have highlighted the need for age-appropriate HL assessment tools that are better aligned with adolescents’ developmental phase, interests, and experiences in the management of health-related information [

44,

45]. Thus, there is a need for a time-efficient and age- and ability-appropriate HL measurement instrument that can be used in adolescents aged 15 years and above.

On the basis of the HLS-EU instruments, the WHO Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy (M-POHL) developed a 47-item instrument (HLS

19-Q47) and adapted short forms—the HLS

19-Q12 and the HLS

19-Q16—to measure the general WHO European Region population HL [

46]. Specific items in the questionnaires were modified and clarified by rephrasing or substituting those that were too complex or difficult to understand, thereby enhancing their comprehensibility for the general population [

44,

47]. To our knowledge, these HLS

19 instruments have been used to measure and investigate HL and its domains in the adult population. Although the HLS

19-YP12 questionnaire has been adapted for young people (16–25 years) [

48], we believe that the HLS

19-Q12 could also be appropriate for measuring HL in a young population because of its increased clarity and acceptability due to its brevity. Consequently, the research questions of the study presented in this article—to measure the HL of adolescents aged 15 years and above, and to determine how HL is related to health behavior—were investigated by using the HLS

19-Q47 adapted short form, the HLS

19-Q12, which is more transparent and more acceptable to adolescents due to its brevity. To answer these questions, we aimed (a) to examine the structural validity and reliability of the HLS

19-Q12, (b) to measure the general HL of adolescents, and (c) to assess the relationship between adolescents’ HL and health behavior.

4. Discussion

This study focused on adolescents’ HL using the HLS19-Q12 instruments and health behavior, examining the relationship between these two items. To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Lithuania to examine HL and its associated factors among adolescents aged 15–19 years. Additionally, it represents the inaugural effort to assess HL in adolescents within this age group using the HLS19-Q12 instrument.

The HLS

19-Q12 is a relatively recent survey instrument designed to assess HL. It aligns with the theoretical framework of HL proposed by Sorensen et al. [

1] while being significantly more concise. Research indicates that adolescents often struggle to complete longer versions of the questionnaire, particularly when they are less familiar with or lack experience with the topics addressed in the statements [

44]. Consequently, the shorter version may facilitate data collection, especially when additional variables need to be measured within the same survey. As we embark on research involving adolescents utilizing this survey instrument, our initial focus is to evaluate the factorial validity and reliability of this questionnaire.

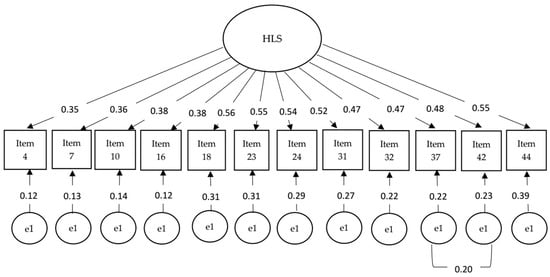

Our findings showed that the HLS

19-Q12 has good reliability and adequate structural validity. We used the CFA model to test structural validity, which aligns well with the data, suggesting that the HLS

19-Q12 items can be effectively modeled as obvious variables of a single latent variable [

46]. Our CFA results indicated that a single factor adequately represented the data, confirming that the HLS

19-Q12 is a unidimensional tool for assessing general HL among 15–19-year-old adolescents.

It is relevant to mention that when testing the construct validity of this questionnaire with Lithuanian PE teachers, the model fit indices were slightly better with adolescent data [

39]. This study confirmed the good reliability of the HLS

19-Q12 by evaluating Cronbach’s and McDonald’s omega. Previous studies with the youth showed very similar reliability (ω = 0.86) of this instrument with a sample of young people aged 16–25 years [

48]. Interestingly, in our study, the reliability was higher than that reported in a survey conducted by Pelikan and colleagues [

46] in 17 European countries (ranging from 0.64–0.86) and slightly lower (0.93) than that reported by Liu and colleagues [

59] regarding a survey in a Chinese adult population. In addition, this instrument showed a lower reliability coefficient in a study with Lithuanian PE teachers (α = 0.73 and ω = 0.75) [

39]. This raises the question of whether there is a difference in reliability between the long version (HLS-EU-Q47) and the short version in studies with adolescents. In Lithuania, only a few studies have used the long version with pupils [

60], but they did not provide reliability data. Notably, one study tested a shorter version of the HL questionnaire, specifically the HLS-EU-Q16, with adolescents in grades 8–12 [

61]. The results showed that the internal consistency (McDonald’s omega coefficient) of the 16-item scale was 0.84, which is slightly lower than that in our study using HLS

19-Q12. Hence, the results do not suggest that the HLS

19-Q12 is superior in measuring adolescents’ HL than the HLS-EU-Q47. However, acceptable structural validity and reliability data indicate that this shorter instrument could be more suitable for examining adolescents’ HL because of its brevity and lower time-consuming costs.

After the structural validity and reliability of the HLS-19-Q12 were evaluated, the second aim of our study was to measure the general HL of adolescents. We found that the overall HL score in our sample was 84.38 ± 18.80, which is higher than that reported by other researchers in the adult population [

46,

59,

62] and slightly different from that reported in the Lithuanian population of physical education teachers (85.09 ± 17.23) [

39]. HL is a critical factor influencing individual health outcomes and can vary considerably across countries. Our survey revealed that a quarter (25.5%) of the adolescents had excellent HL, fewer than half (41.6%) had sufficient HL, fewer than one-third (27.7%) had problematic HL, and 5.2% had inadequate HL. A study conducted in Lithuania with pupils in grades 7–10 [

28] revealed that a smaller proportion (17.4%) of younger pupils had excellent HL. A study in Turkey with pupils in grades 6–8 [

63] showed similar results (17.7%), whereas a study conducted by Pakkari et al. [

64] in Finland revealed that 34.0% of pupils aged 13–15 years achieved a high level of HL. Another study in Turkey with older adolescents (which is more in line with our research participants) revealed results that are closer to those we obtained, i.e., it was found that 21.6% had a high level of HL [

42]. A study conducted in Poland with 17-year-old adolescents also found that 17.0% had a high level of HL [

65]. In contrast to these findings, evidence suggests that adolescents in Germany may exhibit lower levels of HL: a study conducted by Berens et al. [

66] indicated that only 10.3% of young people aged 15–29 years possess excellent HL. These differences may be attributed to variations in age, as older pupils participated in our study, as well as to different HL measurement instruments and disparities in educational systems. Specifically, in the Finnish education system, health issues are taught as a distinct subject, which is a mandatory component of both primary and secondary education, whereas in Lithuania, health education is integrated into different educational subjects. It is noteworthy that comparing our results with those of other studies that utilized the same HLS

19-Q12, we observed that a greater proportion of respondents in our study (67.1%) demonstrated excellent and adequate HL than did the adult population across 17 European countries (55%) [

46]. Additionally, the proportion of respondents in our study was slightly lower than that found in the Lithuanian population of physical education teachers, which was 68.1% [

39].

In our research, boys had higher HL scores than girls. This finding aligns with earlier studies [

67]. However, findings on gender differences are contradictory; some studies have indicated no gender differences [

31,

68], whereas others have suggested higher levels of HL for girls [

25,

61]. Furthermore, studies in adolescents [

31,

69,

70] reported that there is a social gradient indicating socioeconomic differences in HL. They emphasized that the lower socioeconomic status of the family increases the likelihood that adolescents will have lower HL. Our results are very much in line with those of previous research, which shows that family affluence is significantly associated with adolescent HL [

31,

71,

72,

73].

The third aim of our research was to evaluate the associations between adolescents’ HL and health behavior determinants. Previous research has shown a link between adolescents’ HL and health behaviors [

17,

27,

74,

75,

76]. In our study, we evaluated the relationships between HL and various health determinants, including physical activity, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. Previous research has indicated a positive association between HL and physical activity [

27,

77,

78]. The results of our study support this assertion. We identified a positive association between HL and physical activity: adolescents with higher levels of HL are more physically active.

We identified a positive relationship between HL and self-rated health. Similar findings were reported in previous studies on the effects of HL and self-rated health [

26,

29,

30,

31,

72]. Our study also revealed the negative effect of HL on adolescents’ alcohol use during their lifetime and during the last 30 days. Previous studies also found that higher levels of HL are associated with lower alcohol consumption among adolescents [

24,

25,

26]. Notably, we found a negative relationship between HL and smoking during one’s lifetime but not during the last 30 days. Some previous studies have revealed that HL is significantly negatively associated with smoking in the last 30 days [

25,

78]. On the other hand, these studies, unlike our study, did not assess lifetime smoking. Smoking in the past month may only reflect a temporary behavior rather than a habit or strong dependence on nicotine. Previous meta-analyses have shown that insufficient health literacy is specifically linked to nicotine dependence [

79]. Other studies on youth have also indicated that the effect of health literacy on smoking habits (i.e., how long one smokes) is greater than its effect on smoking frequency [

80]. On the other hand, the relationships between lifetime smoking and smoking in the last 30 days may differ across various HL domains [

81]. Therefore, the data suggest that we should consider how smoking habits are assessed—whether to focus solely on recent smoking (e.g., in the last month), lifetime smoking, or both. Additionally, it is important to understand what adolescents associate with smoking.

Although we studied the associations between HL and health behavior, it is also worth discussing the data on the health behavior of adolescents. Our findings indicated that boys were more physically active and had better self-rated health than girls. At the same time, older adolescents are less physically active, are more likely to have smoked in their lifetime and during the last 30 days, and have used alcohol per lifetime and during the last 30 days. These findings align with earlier studies showing gender [

23,

82,

83,

84] and age differences [

85] in physical activity and gender differences in self-rated health [

31]. Our study confirms the findings of other researchers that family affluence is an important indicator of health in adolescents. Young people with low family affluence had lower levels of physical activity [

86] and lower self-rated health [

26]. We found no differences in alcohol consumption or smoking by gender, although other studies have reported differences when adolescents are compared by gender [

87]. However, some trends show that the gap between boys and girls is narrowing [

88].

In summary, this is the first study in Lithuania to explore HL using the HLS19-Q12 instrument and to analyze the determinants of HL and health behaviors among adolescents aged 15–19 years. The study revealed important data about adolescents’ HL. The results also confirmed that the Lithuanian version of the HLS19-Q12 possesses sufficient structural validity and reliability. We also examined the effects of HL on health behavior and lifestyle among adolescents.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the aforementioned strengths of the study, it also has several limitations. Given that participation was voluntary, individuals who chose not to participate may have had lower HL, which raises the potential for selection bias in the study. Furthermore, although the sample size of the adolescent survey is large enough, it is not representative of the entire adolescent population in the country. It is also important to note the potential self-report biases in health behavior measurements, especially when participants are asked to report their behavior over an extended period of time. Also, since this was a cross-sectional study, the data obtained do not allow us to establish causal relationships between health literacy and health behavioral indicators.

We encourage further research to test the validity and reliability of the HLS

19-Q12 instrument among adolescents in other countries. It would also be appropriate to assess adolescents’ digital HL when examining their HL. A recent scoping review showed increased research interest in digital HL and also found positive relations between digital HL and health-related decisions, mental health, and overall quality of life [

89]. Other recent reviews have also highlighted the importance of digital HL among adolescents, particularly the integration of HL and digital HL when developing health education programs [

90]. However, more research tools for measuring digital HL are available for adults compared to adolescents [

91]. It is worth noting that the HLS19-Consortium of M-POHL [

46,

92] developed not only the HLS

19-Q12 but also a measurement tool for digital HL (HLS

19-DIGI). Additionally, the latter has already been validated among Norwegian adolescents [

93]. Therefore, it is worth considering the use of HLS

19-DIGI when studying both general and digital HL. This would allow us not only to measure levels of HL but also to explore how general and digital HL are related to adolescents’ healthy lifestyles. In exploring the links between HL and healthy lifestyle indicators, it would be useful to look at some lifestyle indicators in detail. For example, in the case of smoking, it would be relevant to look not only at tobacco smoking but also at vaping, which has been addressed in recent studies [

94]. At the same time, it would be useful to assess how this relates to HL.